When China's President Jiang Zemin arrived in Washington, D.C., he had more than just his country's growing military and economic might to crow about. At the National Games in Shanghai, Chinese athletes were busy shattering world records in everything from swimming to weight lifting. It was, by any standard, a stunning display: in the weight-lifting arena alone, Chinese women eclipsed every world record in all nine weight classes.

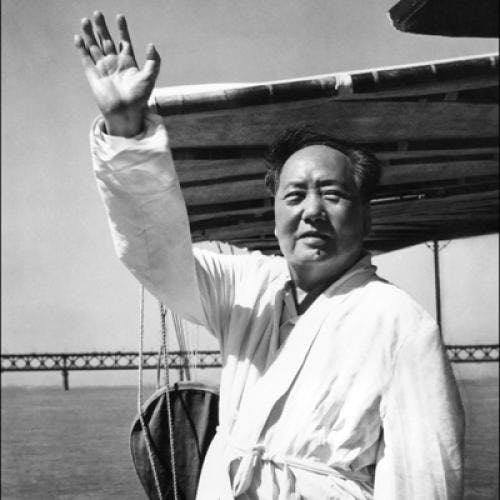

But like so much of China's newfound power, there was something deeply disturbing, even frightening, about these gains. On closer inspection, the results are a little bit too remarkable. In some weight-lifting events, the old marks were surpassed by 60 pounds or more--in a sport which usually measures world record improvements in one- or two-pound increments. In swimming, previously unranked Chinese women set two world records, eight Asian records, and clocked the world's best time in eight of 13 individual women's events. Not since Chairman Mao Zedong reportedly swam five miles down the Yangtze River in 25 minutes have Chinese swimmers sliced so quickly through the water.

What explains this great leap forward? Dope, according to dozens of international observers. And plenty of it. "There's no question about it," said 1996 Olympic swimming champion Susan O'Neill. "The Chinese are cheating, and it's obscene." Added Australia's national swim coach Don Talbot: "It's East Germany all over again." Ironically, the latest uproar about China comes precisely at the same time investigations of more than 100 former Eastern German coaches, trainers, and physicians are beginning in Berlin. Four coaches have been charged with causing bodily harm by administering harmful anabolic steroids to minors.

China, however, seems unconcerned. After failing abysmally at the rigorously drug-tested Atlanta Olympic Games in 1996, Beijing appears to be violating international norms in sports just as it has in the areas of human rights and weapons proliferation. "Everything in my heart and my gut tells me these `records' are fake," said assistant U.S. Olympic coach Mark Schubert, "that they've been achieved by cheating."

Four of China's now top-ranked swimmers previously have never been among the world's top 150 in their events. Indeed, in four of the eight events in which Chinese swimmers rank first, those swimmers previously were not even in the top 50. According to Nick Thierry, secretary of the International Swimming Statisticians Association, no swimmer outside the top 50 has ever broken a world record; in Shanghai, two did.

This disparity has its own quirky logic: swimming's international governing body, FINA, only conducts unannounced drug testing on athletes listed in the top 50, leaving the relative slow pokes to use dope freely. "It saddens me every time I have to add one of these [Chinese] names to the list," said Thierry, who compiles all international records, "knowing that these performances are not legitimate."

Despite China's repeated denials, there are other reasons to suspect China is systematically doping its athletes in anticipation of the 2000 Olympics in Australia. The swimming records broken by Chen Yan and Wu Yanyan, for instance, had been among the toughest in the books. The 400-meter individual medley mark, by Petra Schneider, was the last remaining East German drug-aided record, but Chen lowered it by a second-and-a-half to 4:34.79, swimming some 19 seconds faster than she had in Atlanta. In the 200-meter individual medley, Wu lowered her Atlanta time by seven seconds--and chopped almost two full seconds off the world record.

Adding to the suspicions were the performances by women in the weight-lifting competition--a sport which will make its Olympic debut in 2000. Their performances "are from Mars," said U.S. Coach Lyn Jones. In fact, three lifters, including a bronze medalist, later tested positive for unspecified drugs and were disqualified. (The International Weight Lifting Federation announced it will not recognize any of the new marks.)

On the track, it was much the same story, as three Chinese women destroyed the world record in the 5,000-meter run. Before the Chinese National Games, only one woman (non-Chinese) in the world had broken four minutes this year in the 1,500-meter run; in Shanghai, twelve Chinese broke the four-minute barrier.

As in 1993 and 1994, most of the Chinese distance runners are coached by the redoubtable Ma Junren of Liaoning province, who attributes his athletes' success to his special blend of turtle blood soup, caterpillar fungus, and Chinese herbs. Two years ago, Ma tried to profit from his success, peddling bottles of his concoctions for about $20 each. An independent analysis of the contents of the bottles, secured by John Leonard, chief executive of the World Swimming Coaches Association, revealed that they contained "sugar water." What may really be fueling Ma's army, experts agree, are nondetectable, genetically engineered hormones.

For Ma Junren and other coaches, there is a special incentive to use drugs at the National Games. "It's there that funds are distributed to the top coaches and athletes based on performance," noted famed Australian swim coach and anti-drugs crusader, Forbes Carlile, who coached in China during the 1980s. "A successful athlete or coach stands to earn a great deal of money by Chinese standards--many times the average annual wage."

If the Chinese did cheat, it would not be the first time. Since 1991, 23 Chinese swimmers have tested positive for anabolic steroids--versus just three from the rest of the world. In 1994, the Chinese responded to such revelations much as the East Germans had before them. "We do not use drugs," China's head coach Zhou Ming declared unequivocally. "Our success is due solely to hard work, innovative coaching techniques, and new technology."

One month later, as the Chinese team arrived in Hiroshima, Japan, for the Asian Games, a surprise drug test showed just how innovative those techniques were: eleven Chinese athletes tested positive, all for the same anabolic steroid--dihydrotesterone, or DHT. Because of such repeated incidents, the Chinese were banned from the 1995 Pan Pacific Championships, the first time an entire nation has been excluded from world competition for doping. None of this has apparently deterred China from trying again. Australian Mark Stockwell, a 1984 Olympic silver-medalist, advised his government that if it wants to win in 2000 it "would be better off putting eight million dollars into drug testing in China than investing it in training here in Australia."

Western democracies generally consider international sports a relatively apolitical endeavor--a way to bring nations together. But for China, as for the Soviet Union and East Germany in the past, athletics is an arena of political competition; winning demonstrates both the superiority of its political and economic system, and the greatness of its national power. "Just as our women dominate you now," Zhou Ming has said, "so will our men dominate you in four, five, six years, and so too will we dominate you in world economics." So much for constructive engagement.