In December 1996, Elena Kagan quit her job as a lawyer in the White House counsel's office to return to the University of Chicago, where she was a tenured professor of constitutional law. She had already scheduled the movers, and 120 law students in Chicago had registered for her class. Colleagues had even given her a sendoff in the White House mess. But Bruce Reed, Clinton's new domestic policy chief, begged her to stay, offering her the number two spot on the Domestic Policy Council and promising her an equal partnership running the White House policy shop. It was an unconventional choice, and some in the West Wing wondered why Reed would pick a lawyer to be top wonk.

They don't wonder anymore. Kagan, though virtually unknown outside the White House, has become the administration's lead negotiator on tobacco, crafting much of Senator John McGain's tobacco legislation. The story of Kagan's involvement in hammering out a deal with Senate Republicans illustrates just how active the administration has been in shaping tobacco legislation behind the scenes. Although Reed and White House Chief of Staff Erskine Bowles are the public faces of Clinton's tobacco team, Kagan engineered the White House's most significant win in the tobacco talks so far: convincing McCain and his fellow Senate Republicans to give the Food and Drug Administration full regulatory authority over tobacco, while keeping the administration's bureaucrats at bay.

Giving the FDA broad power over tobacco (which the industry dodged in last year's settlement with state attorneys general) should do more than the blunt instrument of taxes to wipe out smoking. Even if the McCain legislation fails, which seems increasingly likely in light of Republican opposition in the House, the groundwork has been laid for including FDA regulation in whatever tobacco legislation eventually passes. As Kagan puts it: "Having McCain's and [Tennessee Republican Senator] Frist's agreement on this means we have a fairly broad, bipartisan approach, and it will make it into the final legislation regardless of what else is in it."

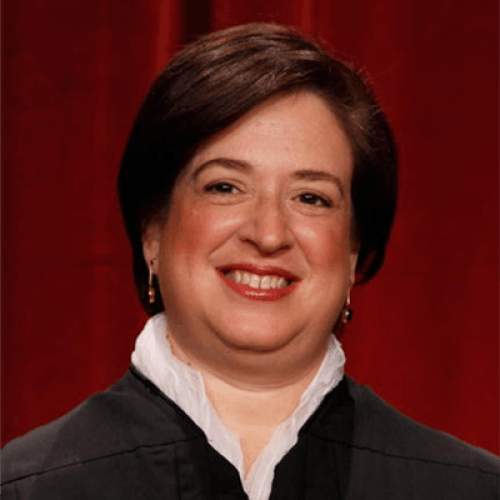

Ironically, Kagan was a teenage smoker herself and quit only in 1993 after 17 years. "I love smoking, and I still miss it," she says. "It's completely clear to me how addictive this product is. But it's also clear to me how much people can enjoy smoking." Now 38 years old, she has a no-frills appearance and a New York accent left over from her childhood on Manhattan's West Side. Kagan met Bruce Reed at Princeton, when she was opinion editor of The Daily Princetonian and he was a columnist. After an Oxford fellowship and Harvard Law School, she clerked for Thurgood Marshall and worked on the Dukakis campaign, then joined the law faculty at Chicago.

Kagan's legal training came in handy in her forays into the minutiae of tobacco legislation. Her moment came in late March, when Reed was vacationing in Europe and Kagan squared off with Republican senators and their staffs on the eve of the Senate Commerce Committee's April 1 markup of the legislation. An earlier proposal by Republican senators James Jeffords and Orrin Hatch had fallen apart over the question of giving regulatory authority to the FDA.

The White House started by arguing that the FDA should regulate tobacco under the "drug and device" chapter in the law, essentially codifying the authority that the agency has already claimed for itself--and which the tobacco industry is currently challenging in court. Senators McCain, Frist, Hatch, and Jeffords all objected, as did the pharmaceutical industry, which feared that it would get harsher treatment along with tobacco. But the FDA insisted on the "drug and device" chapter, figuring that losing this would weaken the regulations and make the agency more vulnerable to court challenges. That might have been the end of it, but Kagan hatched a plan for a separate title under the law for tobacco, giving the FDA virtually the same regulatory language and legal standing it demanded, but moving the wording to another part of the law to soothe the Republicans.

That seemed to hold, but, as late as Friday, March 27, the agreement again was in danger of falling apart when Frist raised new concerns. He worried that, under the new title, the FDA would get authority, over tobacco farmers, not just tobacco, and that the FDA might go too far in limiting retail sales of tobacco or in banning nicotine. Kagan pleaded for 24 hours to work out a deal, and she went through each point with the senator in painstaking detail. Negotiations stretched into the wee hours of the morning. They finally agreed that the FDA would delay by two years any serious action--say, eliminating a class of tobacco product or reducing or eliminating nicotine content--so Congress could review the decision. She also convinced the agencies to accept this token recognition of Congress's prerogatives. Congress, she argued, can reverse FDA decisions anyway. By late Saturday, the deal was done.

Kagan broke a third impasse in the FDA talks when McCain demanded language guaranteeing that the FDA would examine whether its actions could stimulate a black market in tobacco. If, for example, the FDA required all cigarettes to taste awful, smokers would turn to contraband. The FDA balked at such an economic restriction, and talks bogged down. But Kagan "finessed the issue," says Rich Tarplin of the Department of Health and Human Services, who negotiated alongside Kagan and the FDA's William Schultz. She found a legalistic way to give over to McCain without unduly restricting the FDA. Specifically, she agreed to language calling on the FDA to make the black market a "consideration" but assured the FDA it would never be held legally accountable if a black market did develop. Hearing the law professor's case, Schultz and Tarplin consented, and the talks went on.

The Commerce Committee endorsed McCain's bill with a 19 to one vote, and the bill is due to reach the Senate floor the week before Memorial Day. Although it got most of what it wanted, the Clinton administration is still haggling to toughen the bill's so-called "look back" provisions by making penalties for missing teen-smoking reductions company-specific. It also wants to tighten the bill's indoor-air-quality provisions. But these considerations, and even the $1.10-per-pack tax increase over five years, should turn out to be less significant than giving the FDA say over what, where, how, and to whom the tobacco industry sells. The FDA provision was "the toughest nut to crack," says Reed. Without it, "the whole thing would've blown up."

Kagan has become something of an all-purpose brain in a place full of people who are more smart than wise. Last Tuesday, when aides were preparing the president for a meeting, he was stumped about a question on Supreme Court rulings on federalism. Instead of calling the Justice Department or the counsel's office, Clinton sent for Kagan. Clinton and Kagan sat in the Oval Office discussing various rulings, wonk to wonk. On tobacco, her legal experience often allows her to beat hack challenges from her own side, including concerns the Justice Department had about the constitutionality of liability" provisions and of restrictions on cigarette advertising. Normally; objections from the Justice Department would put a halt to negotiations, leaving the White House negotiator furious but powerless. But Kagan "can engage with us and figure out how we can get it done," says David Ogden, who represents the department on tobacco matters.

Kagan uses knowledge as a weapon, absorbing thou sands of pages of legal and policy minutiae and then deploying information to beat down opposing arguments. "I don't want to tell you that she rolled me, but she was coining at me so hard," says a Hill negotiator who opposed Kagan in much of the negotiation. "She reminds me of Bobby Knight's old [University of Indiana basketball] teams that used to wear you down with defense."

The combination of Reed and Kagan, who takes Reed's place twice a week at the daily 7:45 a.m. meeting with Bowles, has made the White House policy operation more prominent than in the early Clinton years. Some resident eggheads had been fluent in policy but politically tone-deaf, drawing complaints of arrogance from the Hill. And academic purists in the agencies have campaigned vigorously against the White House at times. During welfare reform, the scholarly types at HHS fought tooth and nail against the president's executive orders loosening federal regulation of state programs; several academics resigned after Clinton signed the welfare reform law. But Reed has found a hybrid in Kagan, a nerd who can talk tough. John Raidt, the Commerce Committee's staff director, who sat across the table from her through most of the talks, contrasts Kagan's cool performance with the way some other administration negotiators "lash out and get angry, because they don't always know what's going on."

Kagan says she'll see the tobacco law through, but she doubts she'll stick around for the rest of the Clinton years. "I miss the academic life," she says. If she's lucky, she might even land a judgeship. You can picture it now: the woman who vanquished tobacco, in her chambers, surrounded by legal volumes, finishing off an opinion--and reaching into her desk for a lighter and a highly taxed stogie. Cigarettes are out, Kagan says, but "I still smoke the occasional cigar."