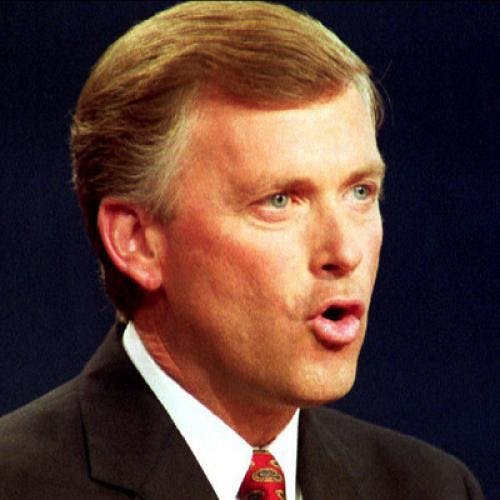

Despite his pee-pants performance in the Omaha debate against Lloyd Bentsen, it looks as if Dan Quayle, 41, will be president one of these days. Consider the politico-actuarial probabilities. Assuming the Republican lead endures, the junior senator from Indiana will be elected vice president. This alone will give him an even chance of becoming president. Three out of the last five presidents were vice president first. Seven out of the last ten vice presidents have ended up heading a national ticket, and four (five if you presumptively count George Bush) got all the way to the Oval Office. Of this century's vice presidents Quayle's age, all became president. Admittedly, the sample is small: T. Roosevelt, vice president at 42 in 1901, and R. Nixon, vice president at 40 in 1953, Still, makes you think, doesn't it?

Vice President Quayle is sure to make his move sooner or later. Maybe later—skinny Yankees like Bush are notoriously long-lived. But maybe sooner. Life is a fragile thing. We live in a hazardous world, A lot of things can happen. Let's say it's next April, and President Bush is out having a brisk springtime sail off Kennebunkport, Maybe he gets his tie caught in the jam cleat. Or maybe, just maybe, he doesn't hear the cry of "Hard to lee!" when the boom sweeps over the deck. Suddenly—bonk! splash!—a vacancy occurs, and J. Danforth Quayle III, maybe still dressed in his lime green golf pants, putter in hand, standing at the club bar, takes the oath of office as the 42nd president of the United States.

At this point, the question becomes the one Quayle so conspicuously failed to answer in Omaha: once we've all had a good pray, what next? The answer, probably, is that the United States would enter a brief Regency period. The regent, in those first panicky months, would be Secretary of State James Baker. For a while, Quayle would perform as he performed in the debate, fearful of disobeying the instructions of his programmers. But as President Quayle gained confidence, the struggle between the Republican moderates and the ideological hard right, formerly assumed to have been settled in the moderates' favor by the nomination and election of Bush, would flare up again, Quayle would grow bored with taking orders from Baker (who, after all, had let it be known during the convention that he had wanted Bush to pick a different running mate) and his Ivy League buddies in the Cabinet junta. The instincts of the vain and unreflective young president would begin to reassert themselves. We can imagine what those instincts might be, given a political character shaped by a grandfather who was one of the most prominent reactionaries of his time, by a father who takes pride to this day in his membership in the John Birch Society, which declared that Dwight Eisenhower was a conscious agent of the communist conspiracy, and by a wife who has spent dozens of hours in her parents' home listening to the tape-recorded rantings of a fundamentalist sect leader named Col. Robert Thieme who often wears his uniform in the pulpit and who believes that the United States government is in the grip of a "satanic conspiracy."

On the foreign policy side, out-of-favor right-wingers who had been careful to praise Quayle during the post- convention days when everybody else was damning himRichard Perle, Jeane Kirkpatrick, Kenneth Adelman— would ascend to glory. On the domestic side, on-the-shelf "cultural conservatives" such as William Bennett and Gary Bauer would stage a similar comeback. With Central America in flames, Soviet-American relations in ruins, NATO turning toward Gorbachev as a source of stability, and police hosing down crowds demonstrating against the appointment of Orrin Hatch to the Supreme Court, conflict between the White House and the Democratic majorities in the House and Senate would escalate to red alert. In 1992 President Quayle would run for a full term as the feisty Midwestern underdog giving "the do-nothing, blame-America-first 102nd Congress" hell. After Reagan's clay-animation cartoon of FDR, Quayle's Truman impression. From the daddy to the caddy.

Or maybe the Age of Quayle will never dawn. The Omaha debate seemed to hold out that possibility. Never in the 28-year history of televised joint appearances by national party nominees has any candidate "lost" so decisively without committing an obvious suicidal gaffe.

The debate was preceded by an unusually Byzantine "expectations" game. Complex signals were coming from the journalists, consultants, and spin doctors who collectively make up what might be called the expectorate. (Or, for purposes of vice presidential commentary, the warm expectorate.) The expectorate's thinking went something like this. Quayle was expected to do poorly. Therefore, Quayle was expected to do well because expectations for him were so low that he could hardly fail to do better than expected. On the other hand, most observers expected Bentsen to do well, but because most observers expected him to do well most observers couldn't see how he could meet the expectations most observers expected of him. That's why most observers expected him to do poorly. In other words—oh, never mind.

By these low standards, I thought Quayle would surely "win." He couldn't. He did all right for about the first 15 minutes, handling the tough, often harsh questions of the panel of reporters in a functional if robotlike manner. Then Tom Brokaw sadistically asked him to describe the last time he had visited a poor family and to tell how he had explained to that family his votes against the school breakfast program, the school lunch program, and the expansion of the child immunization program. In a quavering voice Quayle said he had too met with "those people" and that "they didn't ask me those questions on those votes, because they were glad that I took time out of my schedule to go down and talk about how we're going to get a food bank going . . ."

After this unpleasant display of condescension the debate began to go sour for Quayle. Some of his barbs were still effective, such as his attack on Bentsen's now abandoned $10,000-a-time "breakfast club" for lobbyists ("I'm sure they weren't paying to have com flakes"). Others were not, such as his demagogic promise never to have another grain embargo—or, as he jumpily called it, "another Jimmy Carter grain embargo, Jimmy, Jimmy Carter, Jimmy Carter grain embargo, Jimmy Carter grain embargo." As the minutes ticked away, the admixture of gibberish grew richer, the candidate's manner more and more tense and rigid. Bentsen's now famous saber thrust to the belly—"Senator, you're no Jack Kennedy"—won both ears, the tail, and the debate. But by then Quayle's affect had been thoroughly flattened by the repeated questions about his qual- ifications. Actually, they were questions about what he would do if he suddenly succeeded to the presidency. But the only answer Quayle could find in his mental card file was about his qualifications, so he repeated it—twice, three times, four times—with what appeared to be mounting anxiety. Quayle was like a teenager in a horror movie who thinks the monster has finally been killed, only to have it leap out again from behind a tree. The ritual words they'd given him—I have 12 years of experience in Congress, here are the three big issues, I'll know the Cabinet personally—had no effect. The thing kept coming. When in desperation he used the ultimate incantation, the sacred name of JFK, all it did was bring forth an even worse horror—and this time not from the cackling coven of the press, but from the tall white-haired wizard who until then had seemed courtly if not kindly.

Quayle could have simply said that he would continue the policies of the president he would be succeeding, and could have dared Bentsen to say the same. Instead, Quayle kept talking about how ready and qualified he was to take over the ultimate power, a prospect he seemed to find as frightening as many voters do. In short, he turned himself into one of those "President Quayle" bugaboo buttons the Democrats were handing out beforehand.

The flopsweat was all over Quayle in the second half of the debate. While his slide was less a matter of particular statements than of general demeanor, three mo- ments of supreme silliness do stand out. Asked to name a "work of literature or art" that had im- pressed him lately, Quayle cited a book by Richard Nixon. Also a book by the other senator from Indiana, Richard Lugar, and Nicholas and Alexandra by Robert Massie. One CBS guest commentator said that this answer "came across as non-prepared." I didn't think so, as I had heard it before—in an interview with Quayle a few days earlier. Asked to describe some key experience that had shaped his political philosophy, Quayle said there had been a lot of them, but there was one in particular that he kept coming back to, that he talked about in commencement addresses, that he talked about in high schools, that he talked about in job training centers, that he talked about to his own children, that he talked about to other people's children—on and on went the buildup, and to what? To an incredibly banal piece of advice from his grandmother, namely, "You can do anything you want if you just set your mind to it." When the Democratic claque laughed at this, Quayle added petulantly, "Now the Dukakis supporters sneer at that because it's common sense. They sneer at commonsense advice, Midwestern advice, Midwestern advice from a grandmother to a grandson, important advice, something that we ought to talk about." His problem was immaturity; yet he chose to present himself as a child at his grandma's knee.

Finally there was his closing statement, which he began by saying, somewhat rashly, "You have been able to see Dan Quayle as I really am," and ended by saying, in a flourish that sounded like a literal translation from some language other than English, "George Bush has the experi- ence, and with me the future—a future committed to our family, a future committed to the freedom." What?

The Dan Quayle I followed on his last big pre-debate swing was a happier man than the fearful, angry zombie of the television debate. The three-day trip through the South was probably the least stressful interlude Quayle has had or will have in this campaign. The National Guard business had quieted. Quayle hadn't had a press conference in nearly two weeks (not since the one in which, memorably, he had called the Holocaust "an obscene period in American history" and then, trying to explain that he meant this century's history, blurted out, "I didn't live in this century") and had no plans to have another. He was traveling in magnificent style. His ticket was looking like a winner. All this made for a contented candidate.

To travel with Quayle is to be made more than usually aware of the absurdity of "covering" a fully entouraged American political candidate. It's fun, of course. Traveling with a candidate is always fun, because it's always fun to pal around with one's fellow reporters, ride in chartered airplanes, stay in hotels, and pass through barricades into press sections from which regular people are barred—all at company expense. One enters a movable cocoon of privilege and adventure, a zone of magic. But in the case of Quayle, the zone was touched by twilight. The ratio of miles traveled, pizzas eaten, and expense receipts collected to insights gleaned was unusually high.

Take day two. Quayle "did" a total of seven "events," but only three were open to the press; the other four were closed fund-raisers. At the open events, the press was kept at a distance. We watched Quayle's speech to the students of McNeese State University in Lake Charles, Louisiana, from the balcony of the auditorium. We watched his remarks to Asian Americans in Houston, Texas, from the far end of a hotel ballroom. We watched him address a tarmac rally in El Paso, Texas, from a roped-off section 30 yards away. I had brought a pair of binoculars powerful enough to see the moons of Jupiter. These were much in demand. The plane had two entrances, so there was no danger of encountering the candidate when embarking or disembarking. Total time spent airborne: three-and-a-half hours. Total time spent riding in motorcades: two hours. Total time spent waiting around: three hours. Total time spent watching the candidate read speeches: 55 minutes.

Quayle's role was mostly limited to reading aloud. In speeches, he was permitted to interpolate an occasional interjection—for example, he might say, "And you know what? That's the big difference between us and our opponents," instead of just "That's the big difference between us and our opponents"—but apart from that he stuck closely to the texts handed to him by his minders. I call them minders rather than handlers, the usual term, because the part of the candidate's person they substitute for is the mind, not the hands. Perhaps someday we could have a political campaign in which this pattern is reversed and the staff does the handshaking while the candidate does the thinking.

The tone was set at the very first event, a joint appearance with Bush at a big rally near Nashville. Quayle sailed immediately into his assault on Michael Dukakis. "He is for abortion on demand," Quayle read. "He is against the death penalty for cop killers and drug kingpins. He is for cutting the muscle out of our strategic defense. He is opposed to cutting tcixes. He is opposed to asking teachers in his state to lead students in the Pledge of Allegiance. He supports the American Civil Liberties Union and its extreme positions." And so on. Then the peroration: "Here's my summary. When you review all his positions, you could call him Mr. Tax Increase. You could call him Mr. Polluter. You can call him Mr. Weak on National Defense. You can call him Mr. Weekend Fur- lough. But lemme tell you, my friends, come November 8 there is one thing the American people will never call the man from Massachusetts and that is Mr. President!"

There was a good deal of this sort of thing. The indict- ment of Dukakis was wrong, or at least distorted, in every particular. Dukakis is against capital punishment on principle, but shows no special solicitude for cop killers or drug kingpins. Our strategic defense has no muscle to cut out. Dukakis has no generic opposition to tax cuts; he does oppose the capital gains tax cut for the rich that Bush and Quayle are campaigning for. Dukakis is not opposed to "asking" teachers to lead the Pledge, he's opposed to forc- ing them to do so. Dukakis supports the ACLU, but, like many other members, he does not support its more extreme positions. The minders chose to have Quayle expand on the ACLU point at the Houston meeting of Asian Americans for Bush. It was faintly nauseating to watch this audience of Asian American faces cheering Quayle's attack on one of the few groups that provided leadership in the fight against the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. Nor did they know what they were cheering about. Of the dozen or so I talked to afterward, all said they approved of Quayle's attack, and all said they knew noth- ing about the ACLU other than what they have heard from Bush and Quayle.

There were two unscripted talks—in New Orleans to the National Alliance of Business, and at a Job Corps center in El Paso. Quayle could be trusted to go off the cuff because the subject was the Job Training Partnership Act of 1983, his single legislative achievement. It replaced the old Comprehensive Education and Training Act with a more decentralized, more business-dominated program. Quayle co-sponsored the bill with Edward Kennedy, and when he talks about it he sounds almost like a liberal—a neoliberal, anyway.

"For the first time in our nation's history we've said that a dislocated worker, someone that has no real chance of going back to their place of employment, has the opportunity and the right to receive help through the Job Training Partnership Act. Before, under the CETA program, they were excluded. But we recognize the dynamics that were changing in our society, the dynamics that you have 600,000 businesses that start up in a year, but you also have businesses that don't make it. And we changed the culture and attitude of the work force around to say, 'You shouldn't feel that it's your fault that you lost your job. It's not because you didn't work hard. It's not because you didn't come to work on time. It's not because you weren't willing to invest. The reason you lost the job was because the company made a decision not to continue, through no fault of your own.'..."

This side of Quayle is a puzzlement. To be sure, he faithfully represented business interests in his work on the job training program. Still, it's essentially a liberal program, because it sanctions public intervention in the job market. His work on it is vastly outweighed by an otherwise almost spotless record of opposition to civil rights bills, environmental controls, pro-labor legislation, and measures aimed at helping the poor. Yet his pride in the job training program must mean something. The question is whether it means he is potentially open-minded, intermittently softhearted, or just too intellectually inert to care about being consistent.

If Quayle's training program is aimed at workers who do nothing wrong but whose careers suffer anyway, his own experience is exactly the opposite. Most of us pay some sort of price for screwing up. Quayle never has. His high school guidance counselor told him his grades were too low for admission to DePauw University, where his grandfather was a trustee and major donor, but he got in anyway. In college he flunked the departmental exam that was supposed to be a prerequisite to graduation, but he graduated anyway. Although it was 1969, the height of the Vietnam War, a year when more than a quarter million young men were drafted and other Indianans were being told it would take years to get into the National Guard, Quayle landed a spot in a week flat, after a retired Guard general who worked for his family made a call on his behalf. Quayle was rejected by Indiana University Law School, but he got in anyway—under an affirmative action program, after he visited the dean of admissions, a Republican judge in a city (Indianapolis) where Quayle's grandfather owned the newspaper. (Soon thereafter, the grandfather made a large contribution to the law school.) Quayle was an indifferent law student, but he got a job in the state attorney general's office anyway. (His father had made a few calls.) He was a 29-year-old employee of his father's paper, but he got elected to Congress anyway, with the help of the paper and his own good looks. He was a poor congressman, but he got elected to the Senate anyway, in the 1980 Reagan landslide. Two years later the DePauw faculty voted against giving him an honorary degree, but he got it anyway. He was a mediocre senator, but Bush put him on the national ticket anyway. He blew the debate, but he'll probably be elected vice president anyway. At this rate he'll be president by cherry blossom time.

To my surprise, I was given an interview with Quayle during the flight back to Washington. It had been a successful trip. The minders were feeling expansive. From a distance of two feet Quayle looks younger than he is, his face smooth and creamy, as if unmarked by life. He's good-looking, no denying that. If he were a woman he would be described as beautiful. His facial bones are delicate, and his mouth is what pulp fiction writers call sensual. This gives the lower half of his face a look that is either weak or sensitive, depending on your political predilec- tions. Like his looks, his character seemed soft (in the sense of being unformed). My subjective impression was of a man who has no intellectual depth and not much imagina- tion or empathy, but who is shrewd about the emotional texture of whatever situation he finds himself in. To me, he talked about "our" generation.

I started by asking him how, if at all, experience had caused him to modify the extremely conservative opinions he had been inculcated with since childhood.

"I would say that I've changed on many of the social issues—like civil rights, and things like the Job Training Partnership Act," said Quayle. "Getting government involved in a limited but effective way is a new type of conservative approach. Another difference is an understanding toward the environment and its importance. That gets more into this generational thing. I mean, we grew up with Martin Luther King. I didn't agree with everything he said, but certainly the goals of Martin Luther King are something we all subscribe to, whether you're conserva- tive, liberal. Republican, Democrat—the only exceptions in our generation are those that are on the fringe. The same way with the environment. We are the ones that first experienced this global effect of looking at the problems of the environment.

"Those aren't things that we discussed a lot at the dinner table. The dinner table discussion was more along the lines of very strong anti-Communist feelings. And then there were a lot of good discussions about what you would do on campus, or whether girls would be allowed to visit one's room—things of that sort. So it was a normal type of chitchat that sometimes got confrontational about what was socially acceptable and what wasn't.

"... In our generation things were changing so fast and going on so quickly that I think all people of my generation had that little bit of rebellion and independence with your parents. But in my case never anything that was too extreme. There wasn't any social rebellion where I said, 'Parents, you really don't know what it's all about.' Because I was too close to my parents for that."

"Any intellectual rebellion?" I asked.

"I think my intellectual rebellion, my interests in what I wanted to do from an intellectual basis, was formed much later than most. It wasn't formed in college, but later."

"What were the influences of that later development in terms of people or books?"

"Well, it wouldn't be an intellectual rebellion. I guess I read Charles Reich's The Greening of America in '68 or '69 and at the time I thought it was an interesting book. I haven't reread it, but I've read enough about it that I was really somewhat confused at the time. The sort of thing with the tree layers... That was the sort the book at the time. We all read it and we all talked about it. But as I look back now, it was sort of an exercise in frivolous intellectual curiosity. As far as now, since I've come to the Senate I've been much more interested in trying to focus on what my intellectual approach is. Over spring vacation I read three books that I think were important."

At this point I got the full book report of which Quayle's "work of literature or art" debate answer was merely the executive summary. Hold on to your hat, here it comes: "I read Nixon's book, 1999. I read Richard Lugar's book on The Letters to the Next President. And I read Bob Massie's book on Nicholas and Alexandra. Nixon's book was about the Soviet Union and how we ought to handle them in the future, in 1999. Lugar's was much more of a foreign policy review—the Philippines, South Africa, what we ought to be doing in Nicaragua.... And then Massie's book on Nicholas and Alexandra, which is a really interesting book on the downfall of the Russian czar and the Empire and the coming of Lenin and how that whole thing just crumbled when his father passed on unexpectedly and Alexandra had to take it and they had that child that had hemophilia. And it came through Queen Victoria and everybody sort of thought that the hemophilia was from the high living and they didn't realize it was hereditary. It comes through the mother. And Alexandra was from Germany. And it was a very good book of Rasputin's involvement in that, which shows how people that are really very weird can get into sensitive positions and have a tremendous impact on history."

I lifted an eyebrow; Quayle took a breath.

"Let's see. And then I read other things. Like I read Rick Smith's book on Washington power [Power Game: How Washington Works] It's a good book, and, I thought, very accurate and to the point. So what I've been doing in the last eight years, I've been forming much more of my intellectual basis and pushing on how I really view the world and what the world means to me and how we're going to go forward. I've reread over the last four years both Plato's Republic and Machiavelli's Prince. I've enjoyed that. I was going to go back this summer and make myself read the Republic again but I never got around to it. I don't know if I would have gotten it done on the August break or not. But I was tempted to, because you always learn something by reading the classics. Particularly The Prince. I go through and look at this from this intellectual point of view, which I think is your question. Machiavelli had these three classes of mind, and it fits in so much with Plato's state. The first class was the person that was creative enough to be leader and be able to lead a great nation without much help. The second class of mind was one that wasn't creative but could take ideas, put people around him, and be able to lead nations forward. And the third class of people didn't really know much of anything. And they were the worst kind of leaders, because not only were they not creative, but they didnt' know what was right or wrong and they just sort of went by whatever they felt like. I've tried to figure out where I am. I know I'm not the first one because I don't think I have that creativeness that Machiavelli talks about. If I go back and reread it I might figure it out exactly where I put myself. I'm somewhere in between two and one."

I'm not sure what I can add to this Quayle seemed like a pretty nice guy, and he can be charming. His political views, which is to say the political views of his grandparents and parents and minders, are of course awful. But they are awful in a way that unfortunately has become routine in recent years. The question raised by the prospect of President Quayle is the same question raised by the prospect of President Bush and for that matter by the reality of President Reagan: How long can a great nation afford to have silly leaders?