Diplomat in Carpet Slippers

By Jay Monaghan

(Indianapolis and New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company. 505 pages. $4.)

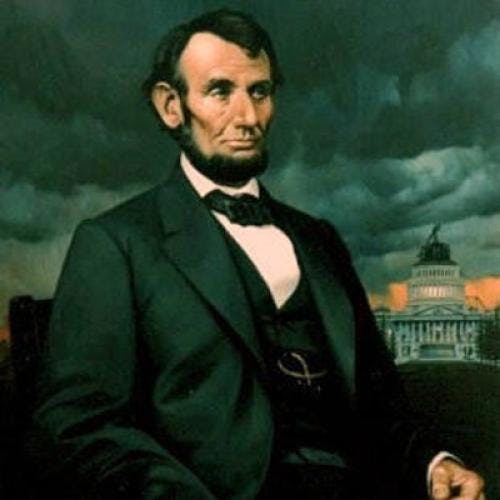

Like most of our great Presidents, Lincoln was a moral hero not only to his own people, but to struggling radicals everywhere. In a fine work of narrative history, which combines in rare fashion humor, imagination and scholarly research, Jay Monaghan reminds us of Lincoln's importance as a world figure.

Lincoln's central diplomatic problem was to fend off British and French intervention on behalf of the Confederacy. He was afraid that need for cotton, fear of Northern tariff policies and the desire to split a potential rival would cause England to support the Confederacy, and he knew that the rebels had the sympathy of the British ruling classes. That his fears were not realized was due in good part to circumstances beyond his influence. War profits reaped by British manufacturers and shippers in time outweighed the inconvenience they suffered from lack of cotton, and after 1862 the chances of foreign intervention rapidly dwindled.

But Lincoln was not passive. He launched a concerted propaganda campaign to convince the people of Europe that the Union was fighting for republican principles against an aristocratic slave power. One of his first acts after Bull Run was to offer a command in the Union Army to Garibaldi, the symbol of world republicanism. The Italian patriot refused; among other reasons, he would fight only in a war for emancipation. But emancipation was not yet in prospect. Whether or not Lincoln preferred to have it so, a large body of opinion in the North and the strategic border states would have refused at the outset to support a war fought to free the slaves. A resolution of Congress early in 1861 stated that the North's aim was to bring the South back into the Union with slavery intact.

Viewed without sentiment, the Civil War thus appears an attempt on the part of the North to deny national self-determination to the majority of Southern whites who desired it. The Union cause was, at the beginning, the cause of centralized nationalism pure and simple; and in the grand political strategy of the conflict it was the Federals, not the boys in gray, who took the offensive. Until emancipation was proclaimed, the war lacked the transcendent moral sanction of a crusade for freedom.

In the face of these facts, Lincoln's prompt success in selling the Union cause to European democrats was no mean accomplishment. The North's war, he told the world, was a defense of a status quo in which the common man had a voice in his destiny and a chance to get ahead. It was a test to determine whether republican government could prevail over an assault from within by forces which were not numerous enough to control it by democratic and pacific means. In Europe republicans took heart from the Union victory. But since the Emancipation Proclamation itself was intended partly as a concession to European opinion, it seems that European liberalism did more for the radical cause in America than Union victory did for liberalism in Europe.

Outright intervention was but one of several delicate problems with which Lincoln had to cope. Mr. Monaghan traces them all with enthusiasm. His book is unlikely to affect prevailing interpretations, and at a few points one may question his judgment and his sensibilities. He cannot understand, for example, why a delegation of free Negroes sat staring mutely when Lincoln proposed to solve the race question by colonizing the freedmen in Central America. But mere conventionality of viewpoint has never been a barrier to the success of a popular book of history, and on other grounds Mr. Monaghan's has a great deal to recommend it. No doubt it will take a prominent place in the Lincoln literature.