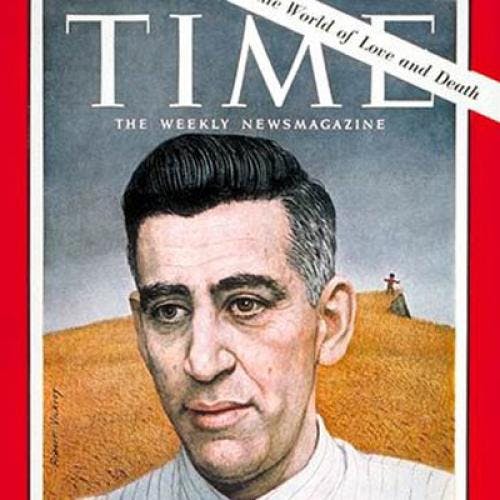

This article was originally published on October 19, 1959.

In his latest work of fiction, J. D. Salinger, speaking through a favorite narrator, makes the following observation about P. B. Shelley, a writer some one hundred-odd years his senior: "I surely think," he says, "that if I were to ask the sixty-odd girls in my two Writing for Publication courses to quote a line, any line, from 'Ozymandias' or even just to tell what the poem is about, it is doubtful whether ten of them could do either, but I'd bet my unrisen tulips that some fifty of them could tell me that Shelley was all for free love and had one wife who wrote Frankenstein, and another who drowned herself." Probably, it would be another safe bet, and one must assume Salinger knows it, that for every ten of Salinger's fans who know anything about the intellectual basis of Zen, a pet subject of his, or the contents of The Bhagavad-Gita, there are at least fifty who know that Holden Caulfield had to go to a psychiatrist ("it killed him, really it did"), and that Franny Glass wasn't pregnant after all. Salinger's Zen is to the faithful like Shelley's Platonism - vague and a little dry. But Holden and Franny - that's different. They are the author's kin, as much kin as Shelley's wives were to Shelley. Information about them is more than mere information; it is intimate lore. And discovering it has led naturally and indiscriminately to the quest for information about the paterfamilias, Salinger himself.

Nobody can fail to recognize that this rampant curiosity about the author - "lurid and partly lurid," Salinger calls it - is one of the most interesting aspects of his reputation. Just how intense the interest is may be hard to gauge, but if his experiences are anything like those of Buddy Glass, the writer through whom Salinger has written much in the last few years, the fifty are already beating a path to his door, planting tire tracks in his rose beds and asking him silly questions about "the endemic American Zeitgeist, just as they have done with Buddy. This is remarkable devotion in a generation as cagey as the present one is supposed to be and yet it might all be conceded to Salinger gracefully enough (fads being what they are) if the body of Salinger's admirers was confined purely to that undergraduate group which sees that it can follow Holden Caulfield's nice line between colloquial earthiness and colloquial mysticism without feeling either too far In or too far Out. But the group is much larger than that, and some people, outside it, have wondered why. About the only explanation Salinger has offered, as he no doubt recalls all the bad imitations of Holden Caulfield, is Buddy Glass' crack, "I have been knighted for my heart-shaped prose."

Going beyond that answer, certain critics, like Maxwell Geismar and John Aldridge, have tried to explain Salinger's appeal by examining some of his favorite themes. Geismar calls Salinger "the spokesman of the Ivy League rebellion of the early Fifties." "Ivy League" means to Geismar that it is a rebellion founded mostly on a dislike for the fancy prep-school phony who abounds in Catcher in the Rye and Salinger's other fiction. For Geismar, and for Aldridge too, the rebellion never quite transcends this adolescent pique at wrong guys and boring teachers. The sympathy of the undergraduate with Salinger can, by this line of reasoning, be reduced to the fact that he doesn't like his roommate any better than Holden does and that he may also share Holden's wish for deafness, or Teddy's wish for death and reincarnation in a quieter world where nobody, for God's sake, is lecturing at him on Western Civilization three or four mornings a week. For Geismar and Aldridge, the "rebellion," thus interpreted, seems irresponsible and "adolescent."

It is hard to argue with their opinion, except to observe that the derogation of “adolescent” has also been applied at different times to Goeth, Schiller, Stern, Byron, Shelley, Keats, Fitzgerald, Wolfe, Hemingway and others. The trouble with such a reduction is that it tends to cancel out Geismar’s equally interesting opinion that Salinger is “the ultimate artist of The New Yorker school of writing,” a compliment which out to have some bearing on our question. Beyond that, their assessment does not do much about telling why the “lurid or partly lurid” curiosity that has always distinguished the interest in Shelley turns today to somebody like Salinger rather than to other writers who are concerned with adolescent and pre-adolescent characters.

Salinger's subject matter is not unique, nor are his positions quite as intelligible as the talk about rebellion would indicate. He has undercut almost every position he has taken, so much so lately that to call him the spokesman for anything seems bold. Probably, if we could find the True Blue Salingerite, that ideal reader who would remain staunchly superior to any ad hoc image of Salinger, he would be no more addicted to rebellion than he would be to Zen. He would, I think, be likely to say that he is interested in Salinger for no better reason than that Salinger's characters are so uncomfortably alive that one has a kind of irrational desire to keep after them and see if something can't be worked out. If pressed, he might guess further that Salinger made them uncomfortable quite deliberately, and that there is an apparently conscious development toward isolating and then enlarging upon the discomforts of the people he is writing about.

This may be put in terms of two propositions; first, that Salinger is offering something different, something presumably more provocative than other writers of his "school" - certainly a good reason for popularity. And, second, that he becomes increasingly interesting to follow because he has changed (and is changing) his own methods after a conscious pattern.

The first proposition is fairly easy to demonstrate. Compare any of Salinger’s stories – they all deal more or less with the indigestible past – and the work of most of the other writers of Reminiscence fiction in The New Yorker and the little quarterlies. The difference is in the half-embarrassed attitude of Salinger’s characters (“I did something very stupid and embarrassing.” “Why do I go on like this?” “I’m a madman, really I am.”). This is a bit more than a trademark; the writers of conventional Reminiscence avoid any tinge of self-consciousness like the plague. While they may be just as jealous of their hunting caps and crocus-yellow neckties as Holden Caulfield and Buddy Glass are, they make it all sound blithely natural and healthy. Where Salinger lurks off in the shadow of his banana tree, they plant themselves under a spreading chestnut, anyway something more solid and less sickly-green. They may experience the same reaction against Today, the same cherishing of Yesterday, but seldom see any implications in so much nostalgia.

The second proposition may be a little subtler. All writers develop in some fashion or another, but Salinger’s development has been especially interesting. As with a singer who evolves a style slowly, much of the pleasure of the audience comes from knowing the stages in his growth.

Salinger’s method has depended all along on a close personal touch with the reader, the shy advance and retreat, the candor about making mistakes, and the tacit assurance that his defense will be seen through; but in its most recent manifestation it feels for the reader’s very heartbeat, tries to catch every flicker of interest or disaffection. By reaching for this kind of communion, it must promise, above all, candor in the difficult writer-reader relationship. Many readers find this concern for staying honest with them particularly appealing; they truly believe (and why not?) that Salinger is trying to get at a more intimate and accurate vision of things than if he took one of the short cuts of form where truths become so facile that they seem more like lies.

Why can’t this be regarded as “development”? Because in Salinger’s early work, even the best, there was the tendency to take these short cuts, to slide through by means of an easy symbol or two, to settle for one of the standard explanations, or appearances of explanation. There, Salinger was criticizing a formulated and formulable society, and his writing derived from some wing of the proletarian tradition in which the gulf between the “lover” and the corrupted bourgeoisie causes most of the suffering of the protagonist. For example, the “banana fever” which afflicts Seymour in the 1948 story, “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” is a result, as far as we can tell, of his wife’s failure of imagination as in the contrast between her telephone conversation with her mother, and Seymour’s scene on the beach where he describes to a little girl the plight of a creature bloated with experience which weighs him down in a society he cannot escape.

But after Catcher in the Rye, an impulse which was latent in the early work began to assert itself. It was an impulse to deal cautiously, but exclusively, with the emotional graph of a single personality: No moments of sudden truth to give the nice terminal epiphany, but rather a series of tentative illuminations, which confess, explicitly and implicitly, the speaker’s lack of any all-encompassing revelation. In “Teddy” and “Franny,” the strain of having to contrive a well-made story had started to show, and afterwards Salinger began his experiment with the longer novella. His distrust of what he calls “beginning-middle-end” fiction stemmed from his awareness of the easy facility not only of the work of others, but of his own. (“Pretty Mouth and Green My Eyes” may have seemed terse and calculable; “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” almost too tidily abstruse.) When Salinger returns to Seymour Glass in the middle-Fifties in order to do him right, Buddy Glass, Seymour’s brother, is moved in to afford a kind of analysis that completely rejects conventional structural formula. Also, in the course of the three most recent stories, the social context in which Seymour moved has been largely forsaken.

At the same time, Salinger has found new ways to keep the reader oriented. While he violates most of the rules of the well-made story as well as the usually sacrosanct convention of the self effacement of the author, he still retains certain organizing principles. In “Seymour: an Introduction,” The device is one familiar in lyric poetry. As the poets have catalogued the charms of their ladies in “Seymour” Buddy takes up one at a time the pertinent characteristics and activities of his brother. A rather droll solution, it nevertheless provides a goal for the story; namely, to make the reader feel Seymour less as a saint and more as a human being. If I pull myself together, Buddy says, Seymour who has killed himself may yet be reconstructed – his eyes, his nose, his ears my rematerialize, even his words may be heard without the echo of the tomb. He is not a dead saint, Buddy tells us, ad we don’t want to think of him as ectoplasm; hence, a tormenting effort to describe his features, his clothes, his poems – anything to make him imperishable.

One by one, the items are ticked off. The poems may be the most embarrassing part of I; they are the hope held in reserve, the means of making Seymour immortal. They are the magic elixir which Buddy keeps half-concealed in the pocket of his coat. He does not really trust the elixir’s effectiveness, so he rationalizes his failure to have had the poems published. The reader may not like them so he prepares to deny their denials of Seymour’s immortality.

The consequences of this method are considerable for in the course of the story, Buddy becomes almost indistinguishable from Seymour. Buddy himself notices this. The object-observed has become the observer. All the air has been pumped out of the bell-jar, time and space continuums are sacrificed, and Buddy and Seymour react so intuitively to each other that there is not reverberation. Consequently, the description of the relationship is so great an effort that buddy breaks into a cold sweat or sinks to the floor for falls ill for weeks in the torture of trying to present a report without any of the ordinary points of reference or means of control.

The objective of the story then in a manner fails. If Seymour in fever was in danger of becoming a saint, Buddy, who identifies too much, has no better luck avoiding the same impression of Seymour in health. No longer the bananafish, Seymour is here metamorphosed into a "curlew sandpiper." He is faster than the Fastest Runner in the World; he makes his profoundest observations in the twilight. He is ephemeral, and no matter how many homely anecdotes are told about him, he has grown too diffuse to look at in the daytime; his talents have become supernatural. Only reincarnation ("and here the first blushes will be the reader's, not mine") could bring him down to earth again, and Buddy knows it, knowing the agonizing failure of his heartshaped prose to do the job.

To use the word "failure" about the story itself is, however, probably almost meaningless to the true Salingerite, for there is a great difference between a failure of purpose ("Does the writer accomplish what he set out to do?") and a failure of effect. In the tradition in which Salinger is now writing, effect is attained not through achieving any goal, any resolution, but rather by getting the effort toward the goal down on the page. However vague that may seem as a criterion, the technical equipment required to meet it with intelligence, integrity, and variety is great. Salinger has submitted to the challenge with particular rigor in the last three stories where the dramatic action in the present has grown increasingly less, and in "Seymour" becomes almost totally expressed in the drama of the individual consciousness, anchored by incidental reports of Buddy's getting up, going to class, getting sick. The past is funneled through by means of letters and personal journals, but remains a part of the struggle of the present.

Corollary to this, it has been important for his enduring appeal that Salinger's narrative procedure has not been associative or "stream of consciousness," a conventional modern reaction against over-rigid form. His syntax is sophisticated and lucid, and in spite of the destruction of the time continuum, he proposes his objectives and makes his digressions (if we want a fictional forebear) with an aplomb like Sterne's, whose techniques those of "Seymour" perhaps most resemble.

Compare, for example, this from Tristram Shandy:

"... It is one comfort at least to me that I lost some four-score ounces of blood this week in a most uncritical fever which attacked me at the beginning of this chapter; so that I still have some hope remaining, it may be in the serous or globular parts of the blood and in the subtle aura of the brain ..."

with Salinger's:

"... I'm really not up to anything that intime just here. (I'm keeping especially close tabs on myself, in fact. It seems to me that this composition has never been in more danger than right now of taking on precisely the informality of underwear.) I've announced a major delay between paragraphs by way of informing the reader that I'm just freshly risen from nine weeks in bed with acute hepatitis .... "

There are dangers in this kind of writing. Sometimes it verges on whimsy, and certainly it can lead to cultishness, as it did with Sterne or with Byron and Shelley, all of whom on occasions got intime with their readers. Also, and particularly with temperaments like Salinger's, it may depend too much on wit to relieve and to steady it. When the humor shows signs of exhaustion and despair, as Byron's and Sterne's did at times, as Salinger's does in "Seymour," the writer may be in trouble.

The body of Salinger's work has been an exploration chiefly of the problem of loss and mutability, free from theories about how a solution may be found. Inasmuch as poets have largely lost interest in such quests since about the time of Tennyson's In Memoriam and that it has made few real inroads into English or American fiction (unlike French and German) since Tennyson, the Salinger vogue is not surprising. It answers a need for a different kind of treatment of experience.

When Buddy Glass asks, "How can I record what I've just recorded and still be happy?" he doesn't answer the question. But there are hints that he is happy with his persistence, and that many of his readers who are up to anything intime are happy with it too.