This article was originally printed on October 1, 1962

It has become a settled conviction, at least among American democratic idealists, that the contest which engulfs the political life of the whole world is between Communism and democracy.

What is Communism? It is an absurd religio-political creed, within the framework of the utopian tradition of Western culture, which erupted with the breakdown of traditional culture in 17th-Century England, 18th-Century France and 19th-Century Russia. The specific content which filled this framework was prompted by the highly contingent circumstances of early European industrialism when an open society, moving too tardily, had not yet proved the capacity of democracy to come to terms with the power realities of modern industry, particularly the aggravation of the disbalances of power in feudal society. Most of the subsequent history of Western democracy has refuted the Communist dogma, particularly that part of it which attributes all historic evils to the one institution of private property. It should be fairly simple to display this refutation and to prove the absurdity of the Communist claims of world redemption from exploitation, imperialism and war.

But unfortunately democratic idealism complicates this simple task by oversimplifying it. It does so by presenting democracy as a universally valid and viable system of government which we are destined to present to the world as an alternative to Communism. This interpretation tends to reduce our cause to utopian dimensions very similar to Communist utopianism. We reduce democracy to utopianism whenever we obscure the fact that it required an advanced European culture centuries (roughly from the 16th to the 19th Century) to make political freedom compatible with the power realities and the collective loyalties of race, language, religion, and class; centuries to validate political freedom (by correcting the disbalances in the economic order) as an instrument of justice. If Communism obscures the triumphs of an open society, democratic idealists likewise tend to obscure the whole tortuous history of that society in European culture: its early chapters of the achievement of ethnic homogeneity, its later chapters in which sufficient tolerance was established to make cultural diversity compatible with communal harmony, and its final chapter of the triumph over the power realities of modern industrialism by achieving a tolerable equilibrium of power in both the political and the economic sphere. The latter development involved the right of laborers to organize and bargain collectively, thus supplementing their equal, but insufficient, political power with equal economic power. This offset the power of centralized management, which according to the Communist dogma represented the final form of evil in history. The whole of the 19th Century was required to achieve this equilibrium. In America it was not achieved until the fourth decade of the 20th Century, when a world depression finally disturbed the complacent bourgeois ethos which had reigned supreme in politics for some 65 years after the close of the Civil War.

Clearly an open society is not the simple option for all peoples and cultures which our democratic idealists assume. It seems to be a combination of an ultimate ideal and a luxury which only a culturally and economically advanced community can afford. It is an ultimate ideal, since no way has been found to make irresponsible power a servant of justice. It is a luxury because only a community with an advanced cultural cohesion and a complicated system of economic mutuality and competition can master the divisive forces which exist in any community. Only such a community can establish its authority over all competitive and divisive forces—and do this without military coercion. Incidentally we might remember that our nation experienced a bloody civil war because we could not solve the slavery issue by democratic accommodation of interests, or suppress an interests which clearly violated the principles upon which the nation was founded.

Merely from the news of the past few weeks, consider the hazards which democratic communities face all over the world. In Algeria, a new nation born in violence, triumphing over the intransigence of French colons and presumably forging a common loyalty through its long liberation struggles, has been threatened with civil war. On the other side, the regime in France, which performed the miracle of extricating itself from the fiction that Algeria was not a nation and liberated Algeria from a power which both tutored her and oppressed her, has suppressed many of the democratic liberties of France in the process.

In Latin America, a democratic leader—President Betancourt—has been threatened by both right and left in Venezuela and just barely managed to triumph over a leftist military revolt. In Argentina, the army has sent the President into exile because, in his effort to establish a democratic regime, he seemed to have flirted with the followers of Peron. In Brazil, that burgeoning wealthy nation none of whose essential problems are solved, the army prevented a leftist Vice President from succeeding a President who had mysteriously resigned, until the constitution was changed to narrow the power of the Presidency to the dimensions of the European rather than the American system. The regime is now in crisis because of friction between the President, the Prime Minister and parliament; and the constitutional amendment which settled the previous crisis is being challenged.

In Peru, where the traditional Latin American feudal pattern of a tight Spanish aristocracy and miserable Indian peasants was challenged by both the top-running Presidential candidates, the army declared the election invalid and has set itself up as a ruling junta. The case of Cuba is too well known to require elaboration. A charismatic leader, Fidel Castro, overthrew the noxious Batista, forgo this promises of constitutional democracy, and is now the prisoner and embarrassed collaborator of the Communists who filled the ideological and organizational vacuum in Castro's movement. In Asia the examples of democratic failure are almost too numerous to record here. In Burma a new military dictator, Ne Win, recently suppressed a student revolt. Ne Win was once the ally of U Nu, the resourceful Buddhist-Socialist leader of what seemed a promising democracy. Recently he overthrew U Nu's democratic regime, charging that U Nu had made concessions to the disaffected regional groups among whom the Communist revolt began a decade ago. He also criticized U Nu for establishing the Buddhist faith in a pluralistic culture.

Korea has had two revolutions since it was rescued from Communist aggression. The present military junta abhorred the corruption of the previous regime. It also rigorously suppressed all political freedom, obviously equating freedom with corruption.

In Pakistan an imaginative and ambitious military dictator, Ayub Khan, suppressed a democratic regime which seemed incapable of triumphing over regionalism and corruption. It is not yet certain whether Ayub can bring about the promised land reform.

In Turkey the military overthrew the Menderes regime and a military junta executed a democratic leader who wanted to use the army to suppress a political revolt. The country is now in a serious parliamentary crisis. The heritage of hate generated by the execution of vanquished opponents is hard to bury.

Vietnam is our client state. We have given it generous military and other aid and defended it against the Communists. But there is evidence that it is little better than a police state and that its standards of honesty are not very high. In Taiwan, the great champion of anti-Communism, Chiang Kai-check, has established a "free China," but it too is a police state. In Iran an amiable and ineffectual Shah has tried vainly to transmute a feudal economy, suppress student revolts, and engage in unpromising land reform schemes.

This list is clearly sketchy and inexpert. It does not do justice to the achievements of democracy in many parts of the world. Such a list does not, moreover, confirm the Communist charge that Americans are the reactionary leaders of reactionary forces in the world. We are merely trying to save the world from the supreme fraud of the ages, the Communist movement which enslaves in the name of redemption. But the evidence does prove that democracy, as it has been elaborated in the advanced nations of the West, is simply not an option for all nations, whatever their level of cultural and economic development. Perhaps the evidence of democracy's failure should serve to modify our own messianic claims. Perhaps we should be more modest and say only that we are trying to help people achieve the highest degree of justice and technical competence they can.

It might be wise to make prudent distinctions between reversible and irreversible experiments in community and order. The irreversible ones are those which are supported by a fixed dogma and a policy which claims omnipotence for an elite, proportioned to its claims of omniscience.

It might also be prudent to analyze more rigorously the hazards which justice (not democracy) confronts in a world in which the rapid universalization of technical ability may aggravate the injustices of traditional communities and may mean both promise and peril to primitive cultures.

In brief, we cannot compete with the Communist utopia by mounting our own utopian claims. We can only modestly admit that history is charged with emergent vitalities on all levels of culture and politics and that it is our task to keep history open for every kind of experimentation, not allowing it to be close prematurely by an absurd and coercive dogma.

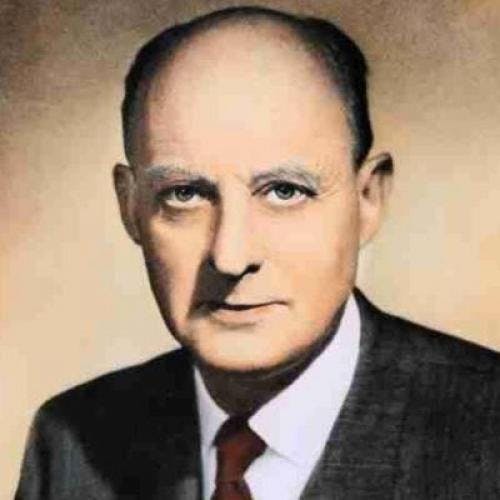

Reinhold Niebuhr, professor emeritus at Union Theological Seminary, is the author of Christian Realism and Political Problems and other books.

For more TNR, become a fan on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.