In times of political demoralization, caricature flourishes. It seems only fitting, then, that David Levine's gift for the visual barb should have emerged in the '60s. For a host of political caricaturists, Vietnam, Watergate, Nixon, Kissinger, student unrest, the drug culture, and the new morality resuscitated their metier. For Levine, there was one additional generative element —the creation of The New York Review of Books during the 1963 newspaper strike in New York. With the Review, Levine's talent had met its opportunity. For though Levine could turn Lyndon Johnson's tears into crocodiles and his abdominal scar into a map of Vietnam, his interests as a caricaturist extended beyond politics, into literature and the arts. For an artist of Levine's breadth, the Review was, and is, an ideal stimulus.

The occasion for this acknowledgment of the range of Levine's talent is an exhibition currently at the Smithsonian's Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and scheduled to travel the country throughout the coming year. Titled "Artists, Authors, and Others: Drawings by David Levine," the exhibition consists entirely of Levine's images of cultural figures. It is a show not without its ironies. Levine considers his major work to be his paintings, representational portraits of garment workers and Coney Island bathers that have been called retarditaire by most of the critical community. The caricatures were an afterthought, a hobby that by chance evolved into a career. Levine soon found that his reverence for tradition, considered so unfortunate in his paintings, was lauded in the caricatures. Their conventions — the huge head on the tiny body, the animal imagery, the facial distortions — are drawn from the vocabulary of 19th century caricature. Sometimes the borrowing is explicit. A drawing of Aubrey Beardsley in the current exhibition takes its long, limp wrists from a 1896 Max Beerbohm caricature of the same subject. Generally, the references are more subtle, but in the format, drawing and tone of Levine's caricatures, Tenniel, Nast, Daumier and Hogarth can all be perceived.

Irony can also be found in Levine's content. Many of the superstars of present critical judgment are Levine's favorite targets. In a recent conversation, Levine discussed the motivation behind some of his more virulent images. The fieriest caricature in the show is a drawing of Jackson Pollock, back to his audience, head turned round, face in his mythic macho glare, his life mingling with his art in a way that Harold Rcisenberg never envisioned. For Levine, this image is retribution for what Pollock "gets away with in painting. An enormous mystique has been built by others around the subjective forms of modern painting, forms that offer no clear communication... Nobody had to take a course to understand Rembrandt."

De Kooning comes off better. Tied to a vibrating machine, the grand old master of abstract expressionism stares out with the gentleness that is part of his personality, if not his art. What saves de Kooning from a caricature akin to Pollock's? "I think he is a better painter than Pollock I think that there is a lot going on with de Kooning. But I think he has a problem with women."

Andy Warhol's problems are bigger. Levine has transformed the superstar of Pop into a hybrid of a pig and Alfred E. Neuman of Mad magazine fame. The caricature is different from most of Levine's images, smaller in scale, the figure dwarfed by the expanse of white paper on which it rests. "I made him small, placing him on the bottom of the page, because I was saying that he is insignificant. I think Warhol actually produces an idiot image. I watched him one night on a talk show where he wouldn't talk. I think taking photographs of anyone wanting a portrait, and turning out multiple photos of cows are put-ons accepted by this driven, crazy art world because of the feeling that no matter what the artist produces they'll have an opening and everyone will have a ball. I don't think Warhol puts as much quality into his art as he did into his window dressing. I saw some of his early window displays, and they were clever. There, the silly game was more applicable. He did silver cut-outs of Victorian shoes, and it looked fine. But the game he has played since then is just nothing."

Obviously, Levine's sympathies reside with writer and fellow caricaturist Tom Wolfe, whose recent book The Painted Word lacerated the art establishment. "Tom produced a marvelous parody, and the up-tightness of the field is such that they couldn't see that he had produced a caricature. They took it as a straight critical essay that was to be questioned in fact and figure . . . "

Like all significant caricatures, Levine's central target is demagoguery, whether in politics or the arts. He is best when he's angry, and it is always easy for an old socialist to get his anger up about the people in power.

"It's fun to tilt at somebody like Picasso. There is a little titilation in that you know that the whole world is just ga-ga about this man, and they haven't had a critical thought about him since the first day....When he was alive, people gushed over him, and there was never a painting referred to as such—it was always 'a Picasso,' which meant the blessing was on it. An enormous industry was built on this—books, curatorial careers, museums—I mean the whole Musuem of Modern Art lived off every time they showed something by Picasso. So with all of that it got to be fun to let people know that all wasn't sacred in the holy house."

Levine applies the same suspicions to politics. "Each time there is a new liberal youngster running, somebody with a shock of hair, a little friendlier kind of PR people rush into his arms. Or they begin to look back at some monster who wasn't able to get into power as being really rather nice because he never got to power. For instance, they think they're all in love with Humphrey again. He had power of a small kind, but he really couldn't let loose the things he would have done. So there is enough material for me still to be very questioning, and I think it is my role to be questioning. This is a nice thing that has happened since the Vietnam war—some political cartoonists like Oliphant . . . have really gotten the idea that they should be critics, and not use their work for something, because there is plenty going for most of these people, and there is very little that is critical."

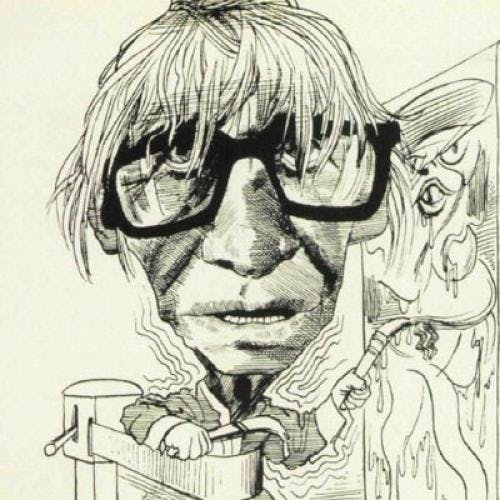

No matter how critical Levine may be of the political and cultural power structures, his work is never savage. Unlike the work of Edward Sorel, it is not chilling. Nor does it possess Jules Feiffer's black humor. Levine's work even in its most strident attacks, is always a pleasing visual experience. He does not search for the weakest aspect of a face or body. Levine likes faces. He enjoys the manipulation of features, and the experimentation with forms that caricature permits. Even in his wildest distortions, there is something attractive about the combination of shapes and forms. Levine's personal pleasure in the act of drawing is evident. Always rich and full blown, his line has none of the terse angularity that makes most caricature jarring. There is a meaningful interplay between flat passages and sculpturesque forms, causing salient features to leap forward into high relief. In his best work, Levine achieves a tonal variety that actually colors the image. Garry Trudeau may bring his "Doonesbury" crew alive with the thinnest of technical means, but for Levine the realization of the drawing takes primacy over all.

Working from photographs, Levine approaches his figures in three basic ways. Often the caricature is a straightforward variation on a subject's face, juggling its lines and features into new, though still atiurate, relationships, just as frequently, Levine will marry facial distortions to animal imagery. For an aging coquette like Colette, for example, a kitten seems perfectly appropriate. The strongest works are those that meld visual qualities with a strong conception. Levine has an amazing knack for suiting accessory to subject. In a way that is more than superficially humorous, Levine can place his figure in a context that implies a profound knowledge of the history and criticism centered around his subject. In his offhand way, Levine dismisses any consideration of profundity, denying any special research for his caricatures. He claims that his reading 'still goes mainly to tennis manuals and art history," and that it is the intellectual insecurities of his audience that add the extra dimension of meaning to his work. "We live in a period in which obscure ideas become mistaken for clever, insightful play on ambiguities...Where I make a reference tbat does not come through in a clear, understandable way, the authority of its appearing in the press, even to intellectuals, creates the feeling, 'Well. I'll have to study up and find out why I don't understand it.'"

Whether be chooses to admit it or not, the success of Levine's work is more than pure luck. His caricatures please even their subjects. Attorney General Levi, for example, recently tried to acquire a drawing that Levine made during his confirmation proceedings. When Levine asked for his FBI dossier in return for the work, the exchange never came off. Generally, however, such setbacks are rare. With an assurance justified by his prodigious talent, Levine continues to turn out his menagerie of homo sapiens.