After an hour in Italy, I wish I'd become an architect. After a week, I begin to think it's not too late. When I gel home, I'll take some stones, pile them up, cover them with stucco, paint my wall a nice earth color, let it age, plain a vine to spill over the top, have a fountain bubbling nearby, and invite everyone over for an aperitivo. The spell of those old stones can hold me clear across the Atlantic. Then I hit Kennedy, and the futility starts to set in; and soon I'm slouched in the back of a broken-down cab, gazing from the expressway over spec housing, gutted factories, commercial strips, and mostly other cars. Arrivederci, architecture.

That's the moment when I grasp the architecture of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. The blissful revelation that real buildings can be prettier than postcards, and the rude awakening from the illusion that their effects can be duplicated anywhere with ease: Venturi and Scott Brown's buildings embody those stales of mind simultaneously. Their buildings start out as shrines to the glories of Western tradition that made Italy every young architect's spiritual home. Then the forms are filtered through a sharp, unsentimental awareness that people came to this country to get away from the conditions that made those glories possible. Then they push beyond that deflating idea to see what can be made from the conditions we've created. No place for architecture? Let's have architecture anyway.

Finally, this past May, Venturi was awarded the Pritzker Architectural Prize. If the Pritzker were as distinguished an award as it's cracked up to be, it would be a scandal that Venturi had to wait in line behind such lesser talents as Philip Johnson and I. M. Pei, and that the prize was not made jointly to Scott Brown, his partner for twenty-five years. (John Rauch, a partner largely responsible for the business end of things, left the firm in 1988.) But the timing of the award is useful. This is the twenty-fifth anniversary of the publication of Venturi's Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, the "gentle manifesto" that set the Post-Modern movement in motion. And it is good to be reminded, now that this movement has run out of the hype that passed for steam, that these begetters of Post-Modernism neither coined the term nor shared the values, at once mincing and crude, that the term came to denote.

Though Venturi was the pivotal figure in nullifying the Modern movement's declaration of independence from history, he was careful not to repeat the error by declaring his independence from a movement as historically rooted as Modernism itself. Modern forms dominate his influential early work. I grew up around the corner from the Philadelphia home that Venturi designed for his mother in 1962, a building often cited as the birthplace of Post-Modernism's revival of tradition. Could have fooled us. With its angular profile, flat surfaces, and quirky windows, the house stood aesthetically on the Modern--that is, the wrong--side of the tracks from the Norman, Georgian, and Tudor mansions where the rest of the neighborhood was living out its upscale fantasy version of William Penn's Greene Countrie Towne. Today, after the Post-Modern deluge of cornices, porticoes, and Corinthian columns, it's hard to see why Guild House, Venturi's 1963 home for the elderly, once had Modernists in an uproar. The building's unorthodox details, such as the small cuts at the roof line that reveal the front elevation to be a facade, or the fat round column at the entrance, only subtly contradict the initial impression that Guild House is an ordinary dumb Modern block of brick.

More important, Venturi's use of un-Modern forms did not so much contradict as resuscitate Modern ideals. His use of sign language from suburban America extended to our own backyard the aesthetic affinity that Modern architects such as Gropius and Le Corbusier once felt for the craft works of exotic and primitive cultures. In drawing on this vernacular, Venturi continued the honorable Modern aim of pushing the gentlemanly an of architecture further along in a democratic direction.

Still, however gentle his intentions, Venturi knew how to jolt. He and Scott Brown bid goodbye to Good Design and headed for Las Vegas. They called their buildings "billdingboards," and they spoke of the need to "accommodate" public taste instead of living to reform it. Tossing aside Modernism's moral stake in "honestly" expressed, architectural structure, the) spoke of buildings as "decorated sheds," and proceeded to decorate exterior walls with stars, stripes, checks, words, and floral patterns lifted from grandma's sofa.

These flamboyant polemics soon got Venturi and Scott Brown pigeonholed as purveyors of architectural kitsch, a reputation they have been at some pains to connter over the years. Venturi has written that "I would like to make it plain that I consider myself an architect who adheres to the Classical tradition of Western architecture." He is right lo insist that his buildings are more than pop cartoons. But why use the term "Classical" to describe an architecture so profoundly at odds with the ideal of order that the term has come to connote: Of course, Venturi and Scott Brown are sympathetic to the traditional association of Classicism with Jeffersonian democracy, even (or especially) in its knock-off version as a Colonial motif for diners and motels. They are populist humanists. Also, Venturi has long found inspiration in sixteenth-century Mannerism, a period when architects pushed the grammar of the Classical orders past orderly bounds. Yet, as John Shearman has observed, Mannerist architecture owes as much to Gothic as to Classical sources. And it has always struck me that the most telling precedent for Venturi and Scott Brown's ideas is the Victorian rage for Venetian Gothic kindled by that arch anti-Classicist, John Ruskin.

Venturi's conception of complexity and contradiction is often taken as an expression of the disorderliness of modern life. (Rudolf Arnheim, for instance, dismissed Complexity and Contradiction as little more than a symptom of modern pathology.) But for Ruskin it was precisely through order that modernity showed its ugly fare. In his own ungentle manifesto. The Stones of Venice, Ruskin begins his attack on Classicism ("this pestilent art of the Renaissance") by denying that architecture has anything to do with order. "I would not impeach love of" order." Ruskin wrote; "it is one of the most useful elements of the English mind; it helps us in our commerce and in all purely practical matters; and it is in many cases one of the foundation stones of morality. Only do not let us suppose that the love of order is love of art."

For Ruskin, Gothic architecture is not primarily a mailer of soaring heights, arched windows, and slender columns that admit light and allow a more open ground plan. Nor docs he view Gothic buildings as examples of structural rationalism, as Viollet-le-Duc viewed them. On the contrary, for Ruskin "The Nature of Gothic" lies in such qualities as Savageness, Disturbed Imagination. Generosity, and Love of Change. He delights in the rich variations of Venetian trucery, startling juxtapositions of pattern, encrusted marble surface's, composite styles. He applauds the architects of the Doge's Palace for not caring whether the large windows on the Molo facade are horizontally aligned:

A modern architect, terrified at the idea of violating

external symmetry, would have … placed the larger

windows at the same level with the other two. … But

the old Venetian … suffered the external appearance

to take care of itself. … And I believe the whole

pile rather gains than loses in effect by the variation

thus obtained in the spaces of wall above and below the

windows.

A century later Venturi showed the same disregard for symmetry in allowing the internal program to affect the size and placement of the windows on the facade of his mother's house.

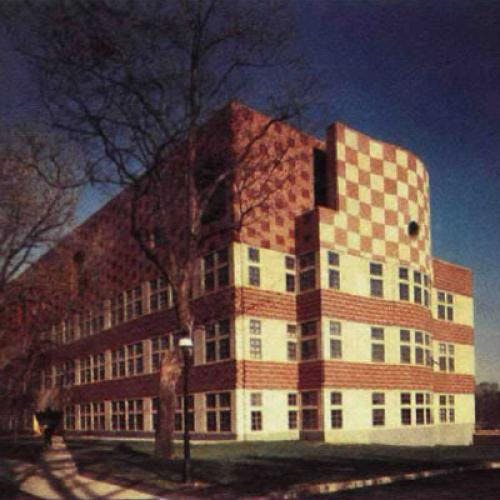

For Ruskin, the Doge's Palace was "the central building of the world," because of its fusion of Byzantine, Gothic, and Classical elements. For me, the Lewis Thomas Laboratory, one of four buildings Venturi and Scott Brown have designed for Princeton University, is the central building in their oeuvre to date, because of the ducal scale on which it pulls together the trio of sources that typically figure in their work: historical allusion (in this case, William Butterfield's Victorian Gothic Revival churches), vernacular forms (New England textile mills), and cues from contemporary art (Robert Kushner's Pattern and Decoration painting from the late 1970s).

Thomas Lab, completed in 1986, is the ultimate decorated shed. It is a giant, 140,000-square-foot rectangular box wrapped up in visual candy: four kinds of check and diaper patterns, executed in polychrome brick and cast stone ornamental brick bands, divide the building's three laboratory floors; rows of square-paned windows, set off by warm stone, weave a tartan of solid and void in acceptably Modern fashion. Bold red checks cover the massive mechanical services floor above the labs; the imposing scale of this floor recalls the top-heavy upper stories of the Doge's Palace, a resemblance that is heightened by the large air-intake ducts that puncture the lab's main facade.

The collage of patterns does not quite bring the building down to human scale; I doubt that Venturi wanted it to. Like a grade school glimpsed for the first time through a young child's fearful eyes, Thomas Lab is Gothic in more than its decorative details. While no cries are heard from tortured prisoners, the ominous, blind sockets of the air ducts hint at potentially ghastly results from the experiments in genetic engineering that are carried out behind the walls. But these whiffs of the sinister are more than dispelled by the building's rosy palette, and by such comic details as the truncated ogee arch at the entrance. Lopped off just beneath the crown as if by careless retrofitting, the portal ushers the visitor into a stately home lately converted into a reformatory for the criminally tasteful.

Thomas Lab was a collaboration between Venturi's firm and Payette Associates, a firm with previous experience in the design of laboratory buildings. Venturi's contribution was primarily decorative; the rationale for his forms is visual and associational rather than structural and programmatic. This is a problem only if you think that structure should dictate form. It would not have been a problem for Ruskin, long reviled by Modernists for his proclamation that "ornament is the principle pun of architecture." And it was Venturi's idea of architecture as a decorated shed that marked the decisive break with the Modern canon.

That canon was largely based on one elementary idea: the desire to eliminate the nineteenth-century schism between architecture and engineering. To "create architecture out of building," in Neal Levine's phrase, instead of regarding architecture as separate from or opposed to methods of construction: this was the great Modern task. But for second-generation Modernists, the task no longer called for major invention; there was little to do but play out variations on the theme. Venturi's book got architecture out of that bind by asking. Why should the outside look like the inside? They are not the same thing. Buildings do more than stand up; they occupy vision as well as ground. Forms don't have to follow functions; they can also perform functions of their own.

The message was liberating, but not anarchic. It arose organically from the Modern premise. Venturi and Scott Brown, too, have made architecture out of building; but for them building is not synonymous with engineering. It refers rather to those forms that have been denied a place in architecture's hierarchical scheme of things: resort hotels, storefront churches, restaurant chains, highway attractions. The function of their forms is to collapse this hierarchy, often into a single image. Thus, an early unbuilt project for the National Football Hall of Fame affixed an electronic billboard lo a Romanesque chapel. The notorious gold "antenna" designed for the roof of Guild House served as a piece of abstract sculpture and as a sign of television's importance to the building's elderly residents. The freestanding pillars in the forecourt of Gordon Wu Hall, their first commission for Princeton, are at once a pair of spheres atop rectangular solids, a jolly cartoon version of a picturesque suburban gale post, and a double echo of the Altar of Fortune designed by Goethe for his Weimar Garden (so blessed a campus must have two altars of fortune).

The layering of associational meanings, the precedence of vision over structure, the playful ordering of forms: these are the ingredients of an American Picturesque, an architecture that seeks to make of the built-up American landscape what eighteenth-century designers brought to English gardens. And it restores to the picturesque its lapsed philosophical dimension as an aesthetic quality "between the Beautiful and the Sublime." For Venturi and Scott Brown, the power of the sublime does not lie with God or Nature, it resides in the Market, with its awesome, leveling assault on the life of the mind. In its buildings, conventions of beauty--of abstract geometric forms, of old world charm--are repeatedly thwarted by glaring commercial interruptions. Soon after Thomas Lab opened, the joke went round that the building's bold checked pattern was a quote from a bag of Ralston pet food: laboratory animals are, after all, the building's only full-time residents. In fact, the firm had employed a similar pattern several years before in its addition to the Oberlin College art museum. But though the pattern may derive from such lofty sources as Butterfield, the scale of its application evokes commercial billboard graphics. (Don't be a paleface; the Oberlin addition rebukes its tasteful Classical neighbor.)

The market is not only a destructive power. It can also be a force for freedom--from dogma, from complacency, from the socially fragmenting pressures of privilege. Wu Hall is clad with bright orange brick. It's not a pretty brick; compared with the patina of the surrounding quadrangles, it looks commercial, more warehouse than college dining hall. One look and you think, Why didn't they use old brick? It would have cost the same and it would have made a better fit. Another look and you recognize that it's not meant to make a better fit. The building is a meditation on the cost of fitting in too well in a privileged enclave ringed by a protective industrial corridor. We can summon up the magic of old world stones well enough, but it takes more than money. It takes a willingness to shut our eyes to where the money comes from, as graduates who hope to live in places this lovely will discover soon enough. Before the ivy begins to creep over our minds, Venturi and Scott Brown break in with a word from our sponsors.

Clearly the Princeton buildings bear little resemblance to what many Modern architects considered "social" architecture: the design of affordable housing, the provision of open space, the planning of entire cities according to rational, humane principles. The social significance of Wu Hall is wholly symbolic. But in fact architecture has been almost wholly consigned to the symbolic level by the increasing privatization of urban life in recent decades. As Scott Brown writes in her new book, Urban Concepts (Academy Editions/St. Martin's Press), "Planning is like a haunted house since we have had Nixon and Reagan." Largely reduced to the role of rubber-stampers for private development initiatives, today's departments of city planning bear little resemblance to the politically empowered agencies that inspired gifted architects of Scott Brown's generation with the ideal of public service.

Urban Concepts presents a selection of the firm's urban design schemes for Miami, Memphis, Princeton, Minneapolis, and other American cities, along with Scott Brown's penetrating analysis of the factors that were reckoned with in each case. What are the social stakes? Who are the constituents for design? What are the limits of architectural solutions? "Who decides what is pro bono publico?"

The book is a polemic as well as a portfolio. Scott Brown presents this work to illustrate the point that the work of her firm has always been strongly rooted in contemporary social concerns. It is not just formal maneuvers. With or without public support for planning, Scott Brown believes that individual buildings can aspire to the social dimension of a plan for regional development. Indeed, she feels that the division between architecture and planning is bad for both professions. For Scott Brown there is a "sociological imagination" as well as a visual one, and architects and planners must embrace both. She objects that Venturi

was not considered an "urban designer" at Penn, because he

dealt mainly with individual buildings. I found this outlook

ridiculous and still do. Whether a building or building

complex is "urban design" or not seems to me to lie not

in its size or its connectedness to other buildings, but

in the way it is approached. A suburban home can be a piece

of urban design, even a teaspoon can be urbane, and a

downtown multistory development ran look as if it were designed

to rise from a green field.

Scott Brown also has a personal ax to grind: a trained architect as well as a planner, she wants to remind us that she is a full collaborator with Venturi in all of the firm's projects.

Hennepin Avenue Entertainment Centrum, an unrealized 1981 redevelopment plan for a major street in downtown Minneapolis, is a good example of Scott Brown's methods for bringing architectural cohesion to a diverse cityscape without sacrificing its diversity. By the time the firm was hired, this former boulevard of legitimate theaters and movie palaces had fallen on hard times, a casualty of the suburban malls. Proliferating peep shows, bars, adult book stores, and rundown hotels had made the street a target for civic cleanup. The risk was that the street's rich architectural mix, including several historic theaters, would be razed to allow the spread of office towers from the adjacent central business district. "The pressure will be to exchange the red silk petticoat image of Hennepin Avenue for a gray flannel one," Scott Brown's report cautioned. "Although a gray flannel image may be suitable to, and a valid requirement of, new office and hotel complexes on Hennepin Avenue, this image on the Avenue as a whole would not benefit the city at large." The plan sought to revive the street's former glory as a regional Rialto, and encourage new development consistent with that aim.

Obviously, as Scott Brown saw it, the market was not the villain here. The market created the buildings and the uses that she wanted to protect, and would be instrumental in reviving them. Her plan sought to preserve, through design control, an environment that once existed without it. In this, it resembles the approach of the nineteenth-century Viennese planner Camillo Sitte, who also sought by deliberate artistic means to hold on to a vanishing culture threatened with extinction. Indeed, if Ruskin is the pertinent antecedent for Venturi and Scott Brown's buildings, Sitte is the philosophical precursor of their urban projects.

For Sitte, too, order was the bane of Modern life. "Modern systems! Yes! To conceive everything systematically, and never to deviate a hair's breadth from the formula once it's established, until all genius is tortured to death, all joyful sense of life suffocated, that is the mark of our time." Sitte's mission was to protect the irregularities of the older, artisan city from further encroachment by the civil engineer's grids. The off-center placement of civic statues, the non-axial organization of town squares and the streets leading into them: by such archaic devices Sitte hoped that new urban development could proceed according to what be considered the "artistic principles" of the medieval city.

Scott Brown also employs analysis and prescription to create effects that initially developed without their aid. But her effects hold a different message. Sitte sought an ideal of cultural unity. An ardent Wagnerian, he wanted architects to create an urban Gesamtkunstwerk designed to steep citizens in awareness of a common cultural heritage. For Sitte, the focus of urban design was the town square. In this social space, streets and people would converge, submerging individual differences in the common pool of community. Scott Brown's aim, by contrast, is to strengthen the ideal of pluralism against creeping homogeneity. For her, the urban focus is the street, a line that cuts across urban differences--skyscrapers, department stores, skid rows, peep shows, Chinese restaurants, parks adorned with the statues of forgotten generals--the entire range of what she calls "taste cultures."

Squares are closed, streets are open, and subject to every force of change. The Hennepin Avenue proposal involved the study of existing buildings and their uses, transportation systems, and growth patterns for the central business district and the metropolitan region. Its recommendations included traffic routes, designs for bus stops, plazas, and skywalks, and the development of design guidelines for future construction. But the main goal of the plan was to give the street a strong visual "entertainment" image. "Sparkle trees," their lofty metal branches festooned with reflecting discs, were designed to line the street at curbside and create "a framework within which the variety will appear complex and not ugly." With the delicacy of Gothic tracery, the trees formed the bones of a honky-tonk chapel for which the street's bright lights and neon signs would provide the stained glass.

The key to this work is that it emphasized perception over construction. Seedy the street may have become, but, as Scott Brown pointed out, Hennepin Avenue "is certainly not dead. … It has a definite character and one that has great potential." The design proposed to develop the potential by helping people to recognize the character, to see beauty and vitality where they might otherwise see only squalor and decay. This approach is miles away from the standard Post-Modern practice of cribbing from European forms. Instead of plopping down an imported temple, the plan sought to raise a temple from the materials at hand. We may not have the means to create a Sainte Chapelle, it said, but the reds and the blues of our neons have their own radiance. We need not romanticize the anonymous craftsmen of the Middle Ages, when our signmakers, display artists, even peep-show operators can do wonders with windows.

Like all of the urban schemes presented here, this one shows the mark of one of Venturi's best-known dictums: "Main Street is almost all right." This idea broke so radically from the Modern prescription to bulldoze cities into blank slates for "total design" that it is easy to miss the curiously Modern thinking behind it. Subtle changes in street lighting, signs, curb lines: What could be closer to the Miesian aesthetic of "almost nothing"? What could be more "less is more" than Scott Brown's belief that pluralism is best accommodated by minimal means? And the underlying idea behind this design--that economic forces should not be spurned but rather channeled toward humane ends--was the central principle on which the Bauhaus was founded.

Scott Brown was not the first to focus attention on the small scale. In the early '60s Jane Jacobs dealt the death blow to the large-scale urban development that Modern architects favored. And Scott Brown's concepts are vulnerable to the same criticism that Lewis Mumford hurled at "Mother Jacobs's home remedies for urban cancer." It's all very well to delight in the colorful threads of the urban fabric. The danger is that enchantment with the small scale can resign us to our failure to deal effectively with large-scale issues of housing, transportation, economic growth, and their impact on the environment. Who cares whether Main Street is almost all right when our urban policies are almost all wrong?

A more serious objection to Scott Brown's approach is that pluralism may be as pernicious a myth as Sitte's Germanic monoculture. It is fine to value diversity, but the risk then arises of creating an image of diversity beneath which the consolidation of economic power and social uniformity can continue as before. True, Scott Brown's approach will not produce the scorched earth policy practiced by Modern architects. The risk with her approach, however, is that it could act like a neutron bomb, preserving the varied texture of cities while encouraging the further displacement of the subcultures responsible for creating the variety in the first place. Or what if those cultures don't want to provide our local color? In the years since Jacobs wrote so lyrically about Mom and Pop candy stores, many of us have found ourselves thinking we would rather watch cities subside into natural ruins than see them turned into theme parks. What's to prevent our appetite for "taste cultures" from turning the city into an endless yuppie smorgasbord of cultural tastes that somehow all taste the same?

Scott Brown is hardly unaware of these problems ("yuppie" is a dirtier word in her lexicon than it is in mine). The great strength of her book, in fact, is that it gives us a framework in which to examine them. What are the alternatives to the "theme park" city? Would we prefer cities to continue along their present course as theme parks of the apocalypse? Should we retreat to the theme parks of social atomization furnished by the suburbs? Urban Concepts does not settle these questions. What it offers instead is a guide to the process of eliciting preferences. As such, the book's most valuable service may be to bring back to the table the awkward topic of taste.

Do we care? Is this a major urban issue? The bridges are crumbling, senior citizens are sleeping in the subways, and our thoughts should turn to taste? Yes, because architecture is a social art, but it is not sociology. It is a partner of social policy, but it is not a substitute for it. Buildings cannot create ideal societies, but if they are to embody social ideals then the issue of taste cannot be avoided, because taste is where art and sociology meet. "Tell me what you like," as Ruskin bluntly put it, "and I will tell you what you are." The question that Venturi and Scott Brown have consistently asked is how architecture, as a social art, can tell us what we are as a society.

Classicism has enjoyed an honored claim as a style for modern democracy because in theory it is a style of orders and laws, and therefore ideal for a civilization that places the rule of law over the rule of men. This was an Enlightenment proposition: the geometric abstraction of late eighteenth-century Neoclassicism proclaimed an affinity with the impersonal laws of nature, and with the "natural" order of human society that philosophers expected to uncover. Two shifts in architecture mark this idea: in style, from Baroque to Neoclassicism, and in building type, from churches and palaces to public and institutional buildings.

The Classical laws are "above taste," as the law of gravity is above opinion. But it was to subjective taste that the architects of the Enlightenment had to appeal, for I with the eclipse of palaces and churches and the authority they exerted, taste became the basis of the social contract on which architectural forms acquire moral significance. In theory, proper cultivation will ensure that taste will concur on correct forms. The role of the academies is to apply the theory. Under academic tutelage, the taste of individuals will converge, like the radial avenues leading toward the Neoclassical public buildings that occupy the center of Ledoux's ideal town of Chaux. The pattern repeated itself in the 1920s, when the Modern movement coalesced around the New Objectivity of Hannes Meyer, Mart Stain, Walter Gropius, and Mies van der Rohe. Once again the associative value of scientific truth was invoked to elevate form above taste; and soon, the academy, this time the Museum of Modern Art, again undertook public instruction.

But what if you weren't convinced? Ruskin's problem with Classicism was not the Modern objection that ancient forms are wrong for modern uses; he objected that the analogy of architecture with science was simply false. "Our architects gravely inform us that, as there are four rules of arithmetic, there are five orders of architecture; we, in our simplicity, think this sounds consistent, and believe them." For Scott Brown, it came as no surprise when MOMA mounted a show of Beaux Arts architecture in 1975. Though MOMA had once opposed the Beaux Arts and everything it stood for, the museum had long been "a pompier of the Modern movement." Its sudden interest in Classicism, she found, served only to subvert the renewal of interest in history and allow "a continuation of [Modern] purism in a new guise."

To recognize the academicism of these movements, however, is not to grant that the academy is invariably wrong, stupid, or an elitist conspiracy foisted on a grumbling public. There is a "taste culture" of architecture itself, a tradition sustained by the impulse to rise above subjective taste through normative order. That impulse is not ignoble, nor is it as divorced from public desires as Ruskin and Scott Brown seem to think. Ruskin erred in presuming to speak for everyone when he wrote that "we take no pleasure in [a Classical building] resembling that which we take in a new book or a new picture." For one thing, writing and painting can be as formulaic as any architectural system; for another, the art of creating a system can be as inventive as the act of breaking one. Precisely because life is messy, it can be very compelling to imagine a life of order, simplicity, and purity, and a great pleasure indeed to look at works by Balanchine, Agnes Martin, Mies van der Rohe, and Buckminster Fuller that give form to that ideal.

Whether or not the Classical vocabulary employed in the Chicago World's Fair of 1893 was appropriate for a democracy in the industrial age, the White City's vision of urban unity proved immensely popular. For years now we've had it drummed into our heads that the public hates Modern architecture. The truth is, many Modern buildings captured the public's imagination with enormous success. People really did gather in the street outside Manufacturers Hanover Trust to gawk at the steel safe gleaming behind the glass curtain wall. It was Hollywood art directors, not a bunch of highbrows, who recognized the powerful mass appeal of the U.N. Secretariat and the Seagram Building. No doubt many people liked these buildings for the "wrong" reasons--because they were novel, or glamorous--but so what? In satisfying our taste for novelty and glamour, these buildings gave bold expression to "who we are." It is only when Modern buildings teased to satisfy this taste, when Lever House was no longer the announcer with the news but merely one pane in an endless wall of glass, that alarm bells went off.

Today many architects feel that their profession is in crisis because there is no academy authorizing a dominant visual vocabulary or a concerted social purpose. Instead, we have good work as varied as that by Frank Gehry, Charles Moore, and Richard Meier, each aligned with a different aesthetic, none enjoying a legitimate claim to represent the only or the best way to design. The "taste culture" of architecture, in other words, is in disarray, despite the heroic efforts of Post-Modernists, Neo-Modernists, and Deconstructionists and their apologists to coax the divergent waters of the mainstream back into that tired old river bed so that it will flow obediently toward them. If it would go too far to credit (or to blame) Venturi and Scott Brown for architecture's current fragmentation, it is at least the case that their inclusive approach, with its implicit rejection of the historicist notion of One Epoch, One Style, anticipated this condition, and remains a viable approach to understanding and even feeling grateful for it.

Taste does not converge on formulas for art and architecture the way experimentation converges on a law of physics. Taste converges on differences: the new tower on the block, the old eyesore left standing, the alternations between order and violation, stasis and change, like and dislike. That is why Ruskin, a supreme moralist, insisted that architects "should be not only correct, but entertaining." That is why, for Venturi and Scott Brown, the city street has been a guiding metaphor, why Thomas Lab plants a billboard in the ivy. The street does not rise above taste, it slices through taste. It tells us who we are by showing us what others like. What is democratic about Venturi and Scott Brown's architecture is not that it is designed by referendum, or even that it tries to be popular, but that, in challenging the normative impulse of architectural "taste culture," it shows how the aims of art and the aims of self-government coincide. Each renews its authority not by its power to enforce laws, but through our power to affect them.