Speaking to supporters on a farm in rural Orford, New Hampshire, Republican gubernatorial candidate Ovide Lamontagne (rhymes with "attain") recounted how his 7-year-old daughter had recently announced her choice for president. "I think maybe we should re-elect Bill Clinton," she said. When her parents explained that Clinton believed in "big government and high taxes," she dutifully recanted. "It was a 7-year-old getting the message," Lamontagne boasted. But he missed the real moral of the story: in New Hampshire this year, Bill Clinton has charmed even the daughter of the state's top Republican candidate.

Since the Civil War, New Hampshire has been the most consistently Republican state east of the Mississippi. Today, its governor, two senators and two congressmen are Republicans. But in this year's election (as in 1992), New Hampshire will likely go for Clinton. More importantly, Democrats lead in the races for governor and senator, and are within striking distance of both congressional seats. Tom Rath, the Republican National Committeeman, thinks Republicans will hold the seats, but he admits, "I can also make a case for the Democrats winning all four." In New Hampshire, that's a minor miracle.

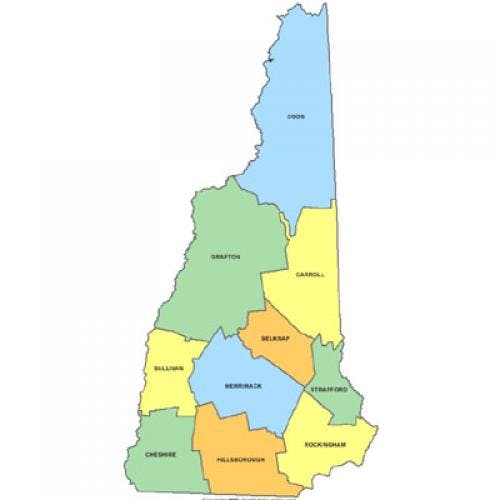

New Hampshire is changing because its people and their work are changing. Once known for its seaport, its textile industry and its farms, New Hampshire's southern tier has become an extension of Massachusetts' Route 128. In the last decade, 800 new software firms have sprung up there. Voters in this populous southern tier resemble those in northern California's Silicon Valley or Raleigh-Durham's Research Triangle. They support women's rights, are suspicious of religious zealotry, and worry about polluted air and streams; they are fiscally conservative (they choose to live in New Hampshire not Massachusetts partly because New Hampshire doesn't have an income or sales tax). Once Republican, they are becoming politically independent. New Hampshire's registered Republicans outnumber Democrats four to three, but by the year 2000 independents will probably outnumber both.

These suburbanites have rejected the traditional conservative Republican formula for winning elections in New Hampshire. This formula, shaped by former governors Meldrim Thomson Jr. and John Sununu and reinforced by the Manchester Union-Leader, mixed anti-tax, anti-government Republicanism (dubbed "the New Hampshire way") with a social conservatism that lured erstwhile Democrats opposed to abortion and gun control. But the new voters don't buy it. They might not like taxes, but they do favor spending on education and environmental regulation. And the Christian Coalition gives them the willies.

Lynne Schmidt is a lifelong Republican from Merrimack, a well-to-do suburb of Nashua. She ran this year as a Republican for state representative and lost. But in the general election she is backing Clinton and the Democratic candidates for governor, senator and congressman. Schmidt's disillusionment with the Republican Party began two years ago, when an organized group, linked to the Christian Coalition, took over Merrimack's school board and tried to introduce Creationism and similar innovations into the curriculum. (See "Into the Wilderness," TNR, October 2, 1995.) Says Schmidt, "Two years ago, I told my in-laws Senator Dole is going to be involved with the Christian Coalition. He sold out to the highest bidder." She rejects this year's Republican candidates for Congress and Senate, arguing that "If we remove the Department of Education, education is going to flounder."

Jim Rubens, a successful Republican entrepreneur who won a state Senate seat in 1994, is backing Dole and Lamontagne, but he is also worried about where the national party is headed. Like Schmidt, he doesn't like the Republicans' ties to the religious right. "The real Republican Party isn't the Christian Coalition," he insists. Rubens is just as worried about the congressional Republican record on the environment. "What they did with environmental laws was an egregious mistake," he says. "Americans don't want dirty air and water. People don't necessarily vote directly on environmental issue unless they are from the Sierra Club, but they now have a sense that a [Republican] politician may do something reckless about the things that they hold near and dear."

To make matters worse, the New Hampshire Republican Party is suffering from the same malady that in the past afflicted some state Democratic parties: as moderates have defected, the party's nominating process has been taken over by hard-liners. This year, the party's gubernatorial and senatorial candidates are both right-wing. Lamontagne, who defeated pro-choice Congressman Bill Zeliff in this fall's low-turnout primary, headed the state board of education, where he was a close ally of the Christian right in Merrimack. Bob Smith, the incumbent Republican senator, won the GOP nomination in 1990 over a pro-choice opponent. In his first term, he has gained notice as a dogged defender of the unborn (he brandished a plastic model of a fetus on the Senate floor) and as a sponsor of legislation to limit company liability for toxic waste spills. He lacks Lamontagne's charm and displays at best a crude intelligence. In an appearance before a Rotary Club breakfast in Bedford, he claimed that by cutting taxes 15 percent, the Republicans could balance the budget in four years. When I asked him how, he had no answer.

While the Republicans have moved right, the Democrats, chastened by past defeat and transformed by the infusion of new arrivals to the state, have nominated moderates. Lamontagne's opponent, state Senator Jean Shaheen, has pledged not to introduce a sales or income tax, but is promising to find new revenues for education. In the Senate race, Smith's opponent, former Congressman Dick Swett, won the primary over an opponent who attacked him for supporting full abortion rights only in the first trimester. Swett, an architect who helps companies design alternative energy systems, is a perfect match for New Hampshire's new high-tech suburban electorate. He eschews the rhetoric of big government but makes a convincing case for using the public sector to expand economic opportunities and to protect the environment. "If the barn burns down," he says, "the community comes in and helps rebuild it, but then everybody goes home and the family gets to farm again. The Republican Party says you must rebuild the barn yourself and run the farm. The Democrats used to say that we'll help you rebuild the farm, so that we can run the farm for you."

Lamontagne has tried to divert debate from education to gambling, charging that Shaheen, who backs video gaming at race tracks to raise revenue, favors "casino gambling." Smith is attacking Swett for taking out-of-state contributions arranged by his father-in-law, Congressman Tom Lantos. "The issue here is out-of-state money," he told the Rotary Club. "It is not Mr. Swett who is raising money here. It is Tom Lantos. If you see people running ads against me, it is from people out of state." (The Manchester Union-Leader, which backs Smith, has highlighted the pro-Israel connections of Swett's out-of-state contributors, which come through Lantos, a refugee from Nazi-occupied Hungary.)

The incumbent Republican is also trying to disguise his voting record. During a question-and-answer session in Bedford, Smith, a foe of education spending and environmental regulation, said, "Someone asked me why did you vote against Headstart. It's because you have a bill that also cuts $50 million for an environmental program." I called Smith's office to find out what environmental program that was. I didn't get a response.

When I asked Republican operatives in Washington about New Hampshire, they had a ready rationalization. The Republicans might lose some races, but, ironically, it's because they've won the debate over policy. Democrats are succeeding only by co-opting their stands. In New Hampshire, however, Republicans are not winning the debate, but evading it. While Democrats like Swett and Shaheen try to develop positions that accommodate both the electorate's distrust of government and its desire for government services, the Republicans are running from their records. Even if their candidates do squeak by this November, Republicans in New Hampshire and elsewhere are going to have to rethink what their party stands for.