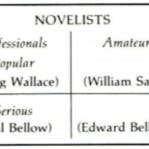

In its long and distinguished history, The New Republic is again about to break new groun: the first four fold table in a book review. (I am feeling the same pangs of achievement as when I invented the "illustrated footnote" while writing a history of American political cartoons.)

The purpose of the following table is to establish some distinctions for reviewing a novel that is not by Saul Bellow and does not pretend to be.

Since the four categories of writers have employed the same genre, some reviewers like to lump them together, obviously to the calculated detriment of the Popular and the Amateur. Thus the reviews cues the reader that he has "standards". He knows the meritorious from the meretricious. If the Amateur is exceptionally skillful (as is Safire), the reviewer can report his "surprise" and still maintain membership of the guild.

The lumping can produce some uneasiness among readers, who do not make the same mistake of equating mysteries with metaphysics. It also produces some unhappiness among writers. The Serious Professional bemoans that he is not popular, i.e., that his books do not make money. The Popular Professional bemoans that he is not taken seriously, i.e. that his books do not receive critical acclaim.

Sometimes, of course, the Serious Professional does make money, often when he sells himself rather thatn his product, viz, Norman Mailer. Sometimes the Popular Professional is taken seriously, usually after he is dead, viz, Dickens and Dostoyevsky.

In general, however, the system works to reward the good Professional who strives to be Popular with the coins of the popular, money, and the good professional who strives to be Serious with the coin of the serious, states (measures in honorary degrees, a festschritt, and the admiration of Benington students.)

The Amateur, on the other hand, is responding to a different drummer. Being a novelist is not what is he trained for, not how he spends most of his time, nor how he would describe himself. If he is a Serious Amateur, his design may be to "educate’ (B.F. Skinner, Leo Szilard); he chooses the form as a way of reaching a mass audience. If he is a Popular Amateur, he simply wants to tell a tale, and sometimes to cash in on notoriety acquires elsewhere (Spiro agnew). He often knows something—presidential politics of iontrigue in academia of aviation—that he think he can explain most usefully in fiction. He is usually a one-book noelist, though not always (Disraeli, C.P. Snow).

So why compare him with Saul Bellow? The reviewer need not feel an obligation to protect the potential buyer. No one is apt to confuse a John Ehrlichman with the most recent Nobel Laureate for Literature.

Here is what he is: An amateus. Hence the purpose of the four-fold table. The distinctions are made. Ifg he is Serious, we must ask whether he has done an effective job of educating us to his point-of-v0ew (Waldin Two no less than Contingencies of Re-Enforcement). If he is Popular, the standards by which we should judge him are: has he amused us, if that is clearly his intention? He has told us enough about something that interests us and that we did not know? In short, has he give us our money’s worth?

In the case of William Safire, former Nixon speechwriter and now a columnist for the The New York Times, the answer is a resounding yes.

Full Disclosure is about presidential politics by a men who intimately knows presidential politics. His novel meets the criterion of telling things we did not know about practices that interest most of us.

The story opens in Yalta with the Soviet Foreign Minister engineering a plot to assassinate the Soviet Premier and the US President, who are riding together in a helicopter. The Premier dies and the President is blinded. The rest of the book concerns the President’s efforts to keep from being declared disabled and removed from office under the 25th Amendment. (In the case of the serious novelist, professional or amateur, the plot is probably secondary and the reviewer is free to reveal as much as necessary to make a point. With the popular novelist, revelation would be bad form. The reader’s satisfaction depends on learning whether the butler did it at the point in the story that the author wants him to have this information, thereby confirming or contradicting the reader’s expectations.)

Safire’s plot surprises. The characters have funny lines. Those who their turn on the stage include a beautiful Official Photographer to the President: a Super-Rich Secretary of the Treasury; an Idealisitic Young Speechwriter, who shares the beautifull Official Photographer with the Lincolnesque President; a lovable Seeing Eye Dog; and a Pompus Ass Columnist. The pace is brisk. There is abundant sex between people of high rank. There are even villains to hiss. Full Disclosure meets the other criterion of those who can afford $10.95. It’s worth it.

For people who feel guilty if they are not reading from the Lower Left, this ain’t it; for those who can find pleasure in the Upper Right; enjoy.