John Lennon was shot on December 8, 1980, finally laying to rest the dream that the Beatles would rise again. Lennon’s murder guaranteed the legend of the Beatles. History is kind to those who do not die in their beds. And the massive mourning surrounding Lennon’s death confirmed the opinions of those who saw the Beatles as not only singers but symbols. A generation that had come of age to their music now mourned not only a hero but a lost hope.

In 1963, when the Beatles emerged from Liverpool onto the national scene, England was in radical transition. The society was changing from being top dog to becoming America’s poodle, from 13 years of Conservative rule to a Labour government. It was the era of the miniskirt and the twist, when the English were beginning to move to new rhythms and to adopt new styles. “I saw no reason why childhood shouldn’t last forever,” the fashion designer Mary Quant said. “I wanted everyone to retain the grace of a child and not to have to become stilted, confined, ugly beings. So I created clothes that worked and moved and allowed people to run, to jump, to leap, to retain their precious freedom.” The Beatles, those “lads” who mixed Cardin chic with Liverpool cheek, embodied the daydream of abundance and eternal youthfulness. Their success was as exciting as their songs. By late 1963, even if Britannia no longer ruled the waves, the Beatles dominated the airwaves. They were at the center of the new boy network of renegade energy and classless achievement. The Beatles’ songs and their public high jinks gave British life the backbeat of promise.

The Beatles coincided with the renaissance in English theater, and they learned to “make show.” The phrase, “Macht show, Beatles! Macht show!” was screamed at them by the owner of the Hamburg club where in 1961 they were losing listeners and business to the livelier bands along the Reeperbahn. Stomping, gyrating, shouting “Nazi” and “Sieg Heil” at the customers, the Beatles soon figured out that a little stage anarchy went a long way at the box office. Having named themselves in homage to Buddy Holly and the Crickets, the Beatles also aped, in their stage carryon, the frenzy of Gene Vincent, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Elvis, and the other American rock ‘n’ rollers whose pulverizing energy they loved. “We had cooked up this whole new British thing,” Paul McCartney later recollected of the Hamburg days, when they were an amalgam of American sound and European fashion. “We had a long time to work it out and make all the mistakes in Hamburg with almost no one watching…A lot of things had been happening with our chemistry…We’d put in a lot of work. In Hamburg we’d work eight hours a day while most bands never worked that hard.” By 1962 the stomping and the “Beatle” hairstyle they’d carried back from Germany (it gave them the look of cuddly Teddy Boys) had turned them from a rock and dole group into the most popular scouse (that is, Liverpudlian) band. Playing lunchtime and evening gigs, the Beatles packed the Cavern, a subterranean rock ‘n’ roll club which tapped the army of adolescents who wanted to get high on music instead of on draft Guinness. The Cavern, which became the Mecca of the Mersey sound after the Beatles vaulted to superstardom, offered a venue for the proliferating number of local bands. Rock ‘n’ roll, like the American kid acts in the early part of this century, put a premium on energy, not expertise; and places like the Cavern were a new kind of vaudeville. As with the vaudeville of yesteryear, the ill-educated, the outcasts, renegades, and dropouts with an ambition to shine but no credentials for conventional success, were attracted to it. They could act out their daydreams of vindictive triumph and get paid for it. “I was always different,” Lennon recalled in Jann Wenner’s Lennon Remembers: The Rolling Stone Interviews (Penguin), voicing the infantile longing behind every star’s obsession. “Why didn’t anybody notice me?”

Lennon especially was noticed by Brian Epstein, the 27-year-oId businessman turned impresario, who had an eye for the boys as well as business. A failed actor who had trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, Epstein encouraged their off-stage theatricality while he coaxed them out of smoking, swearing, and eating on stage. “We were very popular, not being goody-goodies,” Lennon recalled of their success with the tough Liverpool kids. But once Epstein had finally gotten them a record contract (he purchased 10,000 copies of the debut single “Love Me Do” to ensure the Beatles made the Top 20), the act was tarted up for the mass audience. The image of stomping tear-aways was tossed out with their Hamburg leathers. The Beatles now only shook their forelocks. They were “lovable mopheads” and “happy little rockers.” While other English groups like the Rolling Stones and the Who followed the hot, horny message of rock ‘n’ roll and sold the postures of aesthetic outlaws, the Beatles were spectacularly ordinary. They presented themselves as decent English blokes at heart. When they asked for love in their early hit songs, they didn’t shout; they said please. “Oh please, say to me and let me be your man,” they pleaded, wanting only to hold hands. Their songs were more about camaraderie than conquest. “Please, please me,” they sang, just as they had politely bleated on their first record, “So ple-e-e-ease, love me do.”

Before the Beatles, rock ‘n’ roll stars were faces and voices. The Beatles changed that. They took rock ‘n’ roll off the entertainment pages and put it in the headlines. “We turned everything into events,” Lennon said of the group’s genius for making a spectacle of itself, Between October and December 1963, the Beatles, by then boasting a fantastic list of hits including “Please Please Me,” “Ask Me Why,” “From Me to You,” “She Loves You,” were on the front page of at least one major English paper every day. Their music was fresh and fun, but hardly extraordinary. There were Lennon-McGartney songs (like “One After 909”) that only showed them to be slick hit-makers who could sometimes write as shoddily as the next man:

Move over once

Move over twice

Hey baby, don’t be cold as ice.

The Beatles succeeded and survived because they were theater. They turned a press conference into a cabaret and treated the reporters like the Hamburg audiences for whom they made show. Their ad-libs had the wit and vivacity of comic cross-talk:

RINGO: A guy at Decca turned us down.

PAUL: He must be kicking himself now.

JOHN: I ‘ope he kicks himself to death.

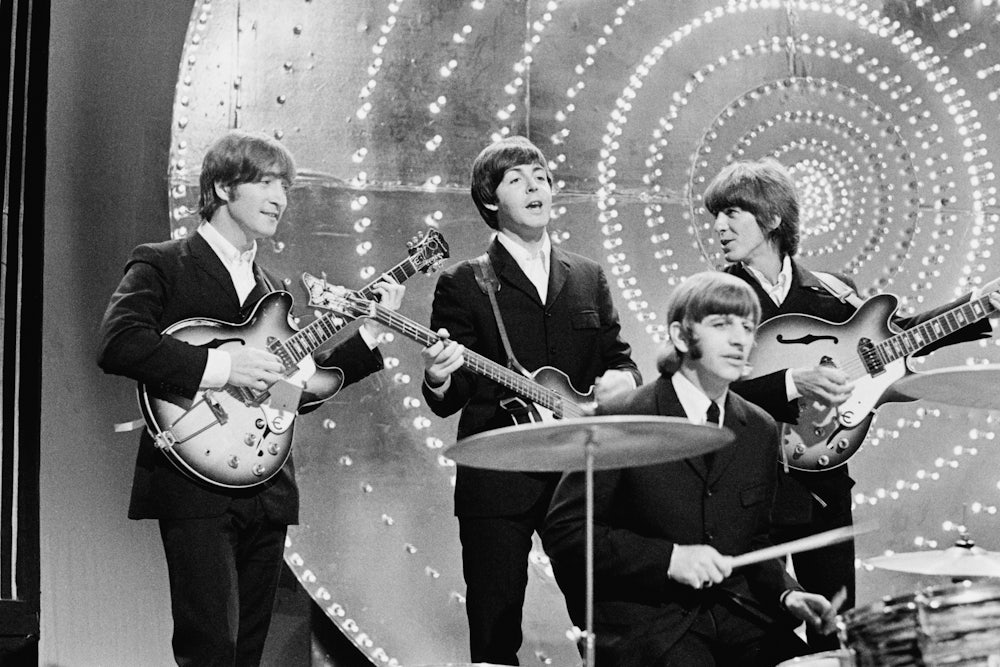

They were not a faceless group of musicians with a new sound, but a collection of affectionate, endearing individuals whose personalities were increasingly acted out in their music. The drummer Ringo Starr, who could barely read or write, was steady, uninspired, constant, good-humored. The lead guitarist George Harrison, the youngest of the group, was intense and introverted. The handsome Paul McCartney, who wrote with John Lennon the songs he sang and actually had some academic and musical training, was flashy, romantic, and professionally charming. Lennon, the founder in 1957 of the Quarry Men, the skiffle band which evolved into the Beatles, was the hard man, the loner, the prankster who best embodied rock ‘n’ roll’s rogue energy. Together, the group’s humanity and high spirits were infectious. As the Beatles became more sophisticated and musically ambitious, they seized on the drama of their differences and built them into their music. Increasingly isolated by their fame, the Beatles drew finally on their past and their future as their only musical subjects. Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), Magical Mystery Tour(1967), Abbey Roadde 2 (1969)—their finest musical achievements--mythologize both their personalities and their problems in song. These records are vaudevilles on disc after they’d stopped touring in 1966--a collection of astonishments and virtuoso turns which carried messages from their own well-publicized lives to their public. Abbey Road, their last recording session before the group broke up over musical and business differences, turns even the group’s disintegration into a spectacular show. Harrison’s “Here Gomes the Sun” holds out the promise of hope and harmony:

Here comes the sun

And I say, ‘It’s all right.’

The hint of harmony is picked up by McCartney’s lullaby “Golden Slumbers” and turned into a bitter nightmare. “Boy,” they sing of their Beatles fame.

You’re gonna carry that weight.

Carry that weight, a long time.

In “The End,” the Lennon-McGartney partnership, recalling their rock ‘n’ roll beginnings, shout:

OH, YEAH!

ALL RIGHT!

Are you gonna be in my dreams tonight?

But instead of the usual Beatles backing, the musicians erupt in an instrumental battle with Ringo performing his first drum solo. “The separation of the four instruments,” writes Milton Okun about the instrumentation in the behemoth, two-volume The Compleat Beatles (Delilah/ATV/Bantam), which includes the arrangements of over 200 of their nearly 300 songs, “can be understood as a musical separation of the group themselves.” There is no musical irony in the Beatles’ poignant farewell:

And in the end the love you take

Is equal to the love you make.

They play the clowns up to the very end, and the record’s coda lightly sidesteps the sadness of their curtain call to cock a snook at royalty. “Her Majesty’s a pretty nice girl,” sings Paul, ending with a throwaway laugh, not a lament. “But she doesn’t have a lot to say.” The Beatles’ end takes them back to their beginning.

At a Royal Gommand Performance given in aid of charity in December 1963, English television viewers got their first prime-time look at the Beatles. They saw John Lennon lean away from his microphone and say: “Those in the cheap seats clap your hands.” Then, glancing up at the Royal Box, where the Queen Mother and her entourage sat, he added: “The rest of you just rattle your jewelry. “The rehearsed quip made headlines. The Royal Family and the general public were at once startled and titillated by this brashness, the unfamiliar voice of the have-nots publically tweaking the noblesse. The style was familiar in the English market stall, but not on the stage. “Taste can be vulgar, but it must never be embarrassing,” lectured Noel Goward, the king of English boulevard entertainment, after the incident. Now the mood of England was brazen and bumptious; and taste could be offensive as long as it had style. The Beatles had plenty of that; and, at least at the beginning, it was earthy, funny, frank, spontaneous, egalitarian. Their films--A Hard Day’s Night and Help!--capitalized on their antic spirit and the public’s love of seeing the “lads” get away with everything.

And everything was exactly what they got. In 1965 the Beatles were given the prestigious Member of the British Empire award (and the public thrilled at the false rumors that John had smoked some reefer in Buckingham Palace). Their biographies were in the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Even Harrods bowed to their whims and extended a tradition only previously offered to the Royal Family. They opened their emporium after hours so the Beatles could shop. By 1968 the Beatles were having their latest single, “Hey Jude,” sent in special gift boxes to the Queen, the Queen Mother, and the Prime Minister.

It was a Labour government that honored the Beatles, and Prime Minister Harold Wilson (the Beatles insisted on mispronouncing his name as “Mr. Dobson”) was quick to exploit his acquaintance with them. But he was not the only world leader who scrambled to wrap himself in the Beatles’ aura. The power of song to unite the body politic in wartime had always been conceded. But the political implications of song in peacetime were suddenly and dramatically apparent with “Beatlemania.” Their music and their phenomenon promoted social contentment on a massive scale.

“Songs,” Plato wrote in Laws, “are spells for souls directed in all earnest to the production of…concord.” “Beatlemania” was a misnomer. Beatles fans were not so much hysterical as spellbound. The Beatles’ music was a form of sympathetic magic, and the Beatles were local divinities who could change the mood and the look of their times by a song, a style, a word. “We’re more popular than Jesus,” Lennon wisecracked; but at first the Beatles didn’t understand either their healing power or their shamanistic role. “It seemed that we were just surrounded by cripples and blind people all the time,” Lennon recalled. “And when we would go through the corridors, they would be touching us.”

Lennon said of the public’s credulity, “They gave us the freedom.” in Magical Mystery Tour, the Beatles teased the power of their spell by dressing up as wizards with wands:

The Magical Mystery Tour is waiting to take you away

Waiting to take you away....

Their music exuded confidence in its enchantment. “Changing a lifestyle and the appearance of youth didn’t just happen,” Lennon told the National Observer in 1973. “We set out to do it.” Song was no longer seen just as entertainment but as a force for social change. As their power to shape consciousness became more apparent to them, the Beatles’ songs spoke more directly to their times. “We started putting out messages,” Lennon explained. The Beatles both molded their era and were a reflection of it. The messages were compelling and simple. “Love, love, love,” the Beatles sang on a TV special, “Our World,” that was beamed instantaneously by satellite to 150 million people waiting for their words, “all you need is love.” A whole generation of radical rebellion and protest was played out behind Lennon’s slogan: “Give Peace a Chance.” (“We don’t have a leader,” Pete Seeger said during the 1967 March on Washington, “but we have a song.”) The Beatles were agents of optimism; their music didn’t fan the flames of discontent, but cooled them in the name of peace. “Don’t you know it’s gonna be alright, alright, alright,” they sang at the height of the 1960s disruption in “Revolution,” a Lennon number that scolded:

But if you want money for people with minds that hate

All I can tell you is brother you have to wait…

Despite the Vietnam War and massive urban unrest, life was celebrated as getting “better, better, better…all the time.”

“We got our ideas off the street,” Lennon said, at a time when the streets ruled, The Beatles took the anxieties and aesthetics of the day and transformed them into an ecstatic experience. In search of their musical and personal identities, the Beatles flirted with mysticism and drugs, those symbolic rebirths which typified the era’s desperate retreat from death-dealing society. The Beatles caught the numbness behind the age’s reckless bravado—”She said, ‘I know what it’s like to be dead’”; “I read the news today, oh boy”—and also the idealism behind its relentless role-playing. These dropouts-turned-rockers-turned-movie stars-turned poet/priests-turned-business tycoons celebrated the myth of transformation which the “changes” in their own lives reflected:

There’s nothing you can do that can’t be done. . . .

Nothing you can make that can’t be made

No one you can save that can’t be saved.

Nothing you can do, but you can learn how to be you in time.

“We were descendants of rock ‘n’ roll,” Lennon explained, after the group had strayed far from its origins and discovered its own musical identity. “We sort of intellectualized it for white folks.” The generation’s search for new imagery was successfully evoked in the visual and aural innovations of their masterful album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The record cover’s Pop Art collage, with the Beatles in the foreground surrounded by scores of their intellectual and personal influences, broadcast the era’s eclecticism which had its musical correlative in the new Beatles pastiche. Sgt. Pepper was a majestic record in which the Beatles broke out into a whole new realm of musical sophistication. It consolidated the experiments made in earlier records: the sound effects of “Yellow Submarine”; the surreal juxtaposition of words to create vivid new images in “Strawberry Fields” (“Living is easy with eyes closed/Misunderstanding is all you see”). Sgt. Pepper was gallimaufry of new and nostalgic sounds: Indian sitar and tabla, military bands, GeorgeFormby music hall backing, electronic crescendo added to which were barking dogs, canned applause, cock crows, a fox hunt. The songs ranged as widely as the sounds, turning the album into an expression of contemporary consciousness: working-class English life in “Lovely Rita” and in “When I’m 64,” which conveys even the syntax of the shabby genteel world it describes; the ever-widening generation gap in “She’s Leaving Home”; the inward-turning mysticism in ‘Within You Without You”; an acid trip in “Lucy In the Sky With Diamonds.” In their acid vision, language is used as a collage of found objects to make surreal images: “a girl with kaleidoscope eyes,””newspaper taxis,” “rocking horse people.” Although this poetic self-consciousness has not worn well with time, their effortless evocation of the small dramas of daily life remains poetic:

Woke up, got out of bed

Dragged a comb across my head…

Even the great finale of the Sgt. Pepper album, “A Day in the Life,” is a collage of two different songs with two opposing moods, which creates at once the sense of escape and the sense of terror that dominated the time. The Beatles’ musical flowering reflected the experiments and the innocence of their age; and their breakup in 1970 foreshadowed the coming disenchantment. “Nothing happened except that we all dressed up,” Lennon said later in his self-imposed American exile. The same bastards are in control. The same people are runnin’ everything, it’s exactly the same. They hyped the kids and the generation.” In their naivete, the Beatles had only reinforced the system they fondly thought they were changing. (Even their company, Apple Records, was conceived, they said, as a form of Western Communism.”) But fame makes the myths of capitalism glorious; and the stars are the performing workhorses of free enterprise that are trotted out to prove that the system works. The Beatles scorned the bourgeoisie, only to find they were the new hipoisie. In Lennon’s apt and angry words, the Beatles were “fab, at myths.”

“It was awful being on the front page of everyone’s life, every day,” George Harrison says in his modest but elegant catalog of songs and Beatle memories, I Me Mine (Simon & Schuster). As the ironic title taken from one of his songs suggests, Harrison has followed the path of Eastern mysticism toward nonattachment, a route somewhat belied by the book and his baronial Oxfordshire estate from which he “watches the river flow.” McCartney, the most conservative of the group, has followed fame’s line of least resistance and become still more rich and famous with his second band. Wings. Ringo good-naturedly wanders the world as actor/singer/drummer, following no particular path. And until Lennon was murdered by a fan, his path had been the most tortuous and musically the most rewarding. He spent much of the 1970s trying to disenchant the public--in songs like “God”--of its appetite for magical solutions. “The Beatles is another myth,” he said. But so far, the Beatles myth has proved stronger than the men who made it. As soloists, none of the former Beatles have attained the impact or the excellence of the group. The genesis of that music and the real lives of the group remain shrouded by the ill-written hagiography about them. The books gloss the orgies and the outrageousness. “Fuckin’ big bastards, that’s what the Beatles were,” John Lennon said in Lennon Remembers, the only book that rings true about the monstrous greed that fame engenders in the most modest heart. “You have to be a big bastard to make it.” Even when the ugliness of Lennon’s own megalomania is frankly exhibited in Lennon Remembers, the Beatles legend keeps its brutality from being seen for what it is. “They can’t feel,” Lennon said, speaking for the public and spouting the blinkered romantic notion of the superiority of the artist. “I’m the one that’s feeling because I’m the one expressing. They live vicariously through me and other artists, and we are the ones…”

Listening to the Beatles’ records again from the long corridor of middle age, the spell is gone. The songs are still delightful, but the thrill surrounding them has vanished as imperceptibly as youth itself. Each lyric conjures automatically the Beatles’ sound. Each sound recalls the definitive phrasing the Beatles gave to their words. Their three-minute epiphanies were, for many, how time was measured and history recalled in the 1960s. Were the Beatles the Schuberts and Bachs of contemporary music? Such lavish comparisons were made, but they hardly seem to matter. Then, as now, the songs ventilated life with their articulate energy. Familiarity has robbed the music of its astonishment, but the songs still have the power to tap ancient longings. “Once there was a way to get back homewards,” Paul’s sweet voice intones with a sense of loss that hits hard in adulthood. The sound of a hard-driving Beatles song, heard as you are inspecting the crows’ feet and the other crenellations of age in the bathroom mirror, can get you moving, mouthing the magic of an earlier time to banish the fear of death. “Yeah, yeah, yeah.” Once again, the old and good times roll. The Beatles’ music makes joy; and that joy, once felt, is never easily forgotten.