There was a certain tidiness to the killings in Youngstown. Usually they happened late at night when there were no witnesses or police and only the lights from the steel furnaces still burned. Sometimes neighbors would hear the short, sharp sound of gunfire and then nothing, a silence you can’t describe unless you’ve heard it, which if you’re lucky you haven’t.

Everyone suspected who the killers were—they lived in the neighborhood, sometimes just down the street—but no one could ever prove anything. Sometimes their methods were simple: a bullet to the back of the head or a bomb strapped under the hood of a car. Or sometimes, like when they got Mr. Magda, they allowed for the more dramatic, tranquilizing their victim with a stun gun and wrapping his head in tape until he could no longer breathe.

Yet the most frightening method, the one that captured the city’s imagination, was the most immaculate: the disappearance of people in broad daylight. They were the city’s ghosts. Police found their cars empty on the side of the street, the engines still warm, or their dinner tables still piled with food. They had, in the most classic sense, been “rubbed out.” The only sign of the killers was an artistic flourish: the dozen long-stemmed white roses victims often received just before they vanished.

So, when Lenny Strollo ordered the hit that summer night in 1996, there was no reason to believe it would go down any differently. As the top Mafia don in Ohio’s Mahoning Valley, he presided over the killings and disappearances in and around Youngstown from his farm in nearby Canfield, where he tended his gardens and ate vitamins to quiet his heart. His reach extended over nearly an entire corner of the state, a stretch of land that was home to more than 200,000 people and that had become, by all accounts, the most crooked county in America—a place, in the modern era, where the Mafia still held sway over every element of society, from the police to the judges to the politicians. Only months earlier, Strollo had ordered his main mob rival mowed down as he drove to work. But this time his choice of target was more brazen: the newly elected county prosecutor, Paul Gains.

The Mafia didn’t ordinarily “take out” public officials, but the 45-year-old prosecutor had so far resisted all the customary overtures, bribes, and campaign contributions, and it was now widely rumored that he planned to hire as his chief investigator the man the Mafia hated most: Bob Kroner, the local FBI agent who had spent 20 years pursuing the mob. In Mafia fashion, Strollo employed endless layers of authority so that nothing could be traced back to him. First he gave the order to Bernie the Jew, the man he relied on for all his muscle. Bernie, in turn, hired Jeffrey Riddle, a black drug dealer turned assassin who was obsessed with the Mafia and, according to friends, boasted that he’d one day be the first nigger ever inducted into the family. Riddle then brought in his own two-man team: Mark Batcho, a fastidious criminal who ran one of the most sophisticated burglary crews in the country, and Antwan “Mo Man” Harris, a crack dealer who, though he still lived with his mother, had already committed at least two other murders.

That Christmas Eve, as Batcho and Harris later recounted, the three men loaded up on everything they needed: walkie-talkies, ski masks, gloves, a bag of cocaine, a police scanner, and a .38 revolver. Around eight o’clock in the evening, they drove out to the prosecutor’s home, in a Youngstown suburb dotted with strip malls. The houses glowed with Christmas lights. But, when they arrived, no one was home. Batcho got out of the car and waited behind a lamppost near the garage. He attached a speed loader to the revolver to enable him to shoot faster and tested the voice-activated walkie-talkie. No one responded. He tried again. Nothing. He couldn’t believe it. Here they were asking him to carry out the premier Mafia hit in years and the equipment was busted. He ran back to the car and said he couldn’t kill anyone without “communication.”

Batcho, Harris, and Riddle regrouped at the Giant Eagle Supermarket on Route 224 and programmed two of their cell phones so they could dial each other at the touch of a button. As they eased up in front of the house again, they noticed that a car was in the driveway and the kitchen lights were on. “OK,” Riddle said, shoving the gun back in Batcho’s hand, “get out and go do this.”

Batcho jumped out of the car, carrying the bag of cocaine Riddle had instructed him to plant on the body to make it look like a drug-related killing. He crept up to the house, his heart pounding. The garage door was open, and he said, “Hey, mister, hey, mister,” but no one answered, and he kept walking. The side door to the house was open, too, and he could hear someone speaking. He decided to go in. Creeping down the corridor, he heard Gains talking on the phone in the kitchen. Batcho rushed in, pointed the gun at the prosecutor’s midsection, and fired. As Gains fell to the ground, Batcho fired again. Blood spilled from two wounds—one in his forearm, the other in his side. Batcho took another step closer as Gains put up his hands to ward him off.

Batcho aimed near Gains’s heart and pulled the trigger. But the gun kicked back in his hand, jamming. Jesus fuckin’ Christ! Batcho turned and ran out of the house, stumbling into the woods in back. He tripped and fell and, getting back up, hit the button on the cell phone, screaming, It’s done! It’s done! Come pick me up! As he came out of the woods, he saw the car approaching down the street and lurched toward it, jumping into the backseat. He crouched down, shivering. “Did you kill him?” Harris and Riddle asked.

“I think so,” Batcho said uncertainly.

“You don’t know?” Riddle said.

“The gun jammed,” Batcho said, “the gun jammed.”

Harris looked at him coolly. “Why didn’t you go in the drawer and get a steak knife and stab him to death?” he asked.

Riddle said they had to go back and finish the job, but just then the police scanner crackled with news of the shooting. Riddle hit the gas and started swerving along the back roads. Fearing they’d get pulled over, Harris took the gun and threw it out the window. But the speed loader was missing. Where the fuck is the speed loader? they started screaming at each other. Then from the scanner came even worse news: Gains was still alive.

It was one of the least skillful murder attempts in the valley’s history: the speed loader was found outside the house, along with a clean footprint; a sketch of the shooter appeared in the paper within days. But, ironically, the crime scene was so messy that investigators couldn’t believe Strollo’s people were behind it—not even Gains, who told friends, If the mob had done it, I’d be dead. Batcho, who had begun to wear disguises around town, slowly emerged from hiding. Amazingly, it looked as if these murderers would get away as well, until one spring night the prosecutor got a phone call at home. “Are you Paul Gains?” a woman asked.

“Yes,” he said, “who’s this?”

“I know who shot you,” she said.

When the woman rattled off details about the crime that few could have known, Gains called the police, who brought in the FBI. “I know everything,” she told the agents who rushed to her apartment the next day. “I know other people they shot. I know everything.”

And so it happened. The call, from the ex-girlfriend of an associate of the hit men, helped solve a mob hit for the first time in the valley’s history. But, coupled with a three-year covert operation by the FBI, it would ultimately help uncover something far broader. It would slowly untangle what authorities describe as one of the last truly mob-run counties in the country: a place where the Mafia still controlled a chief of police, the outgoing prosecutor, the sheriff, the county engineer, members of the local police force, a city law director, several defense attorneys, politicians, judges, and a former assistant U.S. attorney; a place whose residents had grown so used to a culture of corruption that they viewed it casually, even proudly; a place, in a sliver of America, where a malignant way of life was left largely untouched for almost 100 years. Now, after more than 70 convictions, the investigation has wound its way to the most powerful politician in the region, a man whom the FBI caught on tape with the mob nearly 20 years ago but who has eluded them ever since: United States Congressman James Traficant.

Today, the Mahoning Valley is one of the most depressed corners of America. But it wasn’t economic bust that first brought the mob to the valley; it was economic boom. In the early years of the twentieth century, the valley—a thin corridor of land that twists and turns its way through northern Ohio—was the heart of an industrial empire. Steel mills stretched as far as the eye could see, their furnaces streaking the sky with 15-foot flames. For more than 50 years, their lights drew immigrants—Poles and Greeks and Italians and Slovaks who thought they had found the Ruhr Valley of America—as well as a burgeoning class of racketeers who thought they had found their own “Little Chicago.” Youngstown’s streets were lined with after-hours joints, where the steelworkers drank and played Barbut, a Turkish dice game, and where capos, dressed in white-brimmed hats and armed with stilettos, ran the numbers, or “bug,” as the locals called it. Youngstown in the 1940s wasn’t particularly unusual. Like Chicago, Buffalo, or Detroit, it had a teeming immigrant population accustomed to arbitrary and violent authority, a booming economy, and pliable local politicians and police—all the ingredients the mob needed to flourish.

But, unlike those larger cities, Youngstown was too small to have a mob family of its own. And, as a result, it turned into a battlefield. By 1950, as the rackets mushroomed into a multimillion-dollar industry, the Pittsburgh and Cleveland Mafia families began fighting for control of the region. Bombings began to ricochet through the valley—warnings to those who allied themselves with the wrong side. It got so bad over the next two decades that the local radio station ran public-service ads featuring an earsplitting bang and the slogan “Stop the bomb!” In 1963, The Saturday Evening Post dubbed the area “Crimetown U.S.A.,” noting: “Officials hobnob openly with criminals. Arrests of racketeers are rare, convictions rarer still and tough sentences almost unheard of.”

Shortly after Bob Kroner arrived in the valley in 1976 as a 29-year-old FBI agent, a full-scale war broke out. On one side was Joey Naples’s and Lenny Strollo’s faction, which was controlled by the Pittsburgh Mafia; on the other were the Carabbia brothers—known in town as simply “Charlie the Crab” and “Orlie the Crab”—who were aligned with Cleveland. “It seemed like you’d get up every morning and get in your car and hear someone else had been murdered,” says Kroner.

First there were “Spider” and “Peeps”—two petty cons hit within a few weeks of each other. Then came one of Naples’s drivers, shot as he changed a tire in his driveway, and a crony of Peeps’s, who was gunned down outside his apartment. Then, poor John Magda, who was discovered, his head wrapped in tape, at the dump in Struthers, and, next, a small-time bookie who refused to go easily—he was first bombed and later shot through his living-room window while he watched television with his wife. Then, Joey DeRose Sr., killed by accident when he was mistaken for his son, a Carabbia assassin; and finally, a few months later, the son, too. “Oh my God, they got Joey,” his girlfriend screamed when police told her they had found her car burning on a country road between Cleveland and Akron.

A former high school math teacher who turned in his books for a badge in 1971, Kroner quickly plunged into this underworld. He could be seen in town, in his neatly pressed suit and tie, trailing reputed hit men and banging on the doors of the All-American Club. Though he came from a family of cops, Kroner didn’t look like one: he was too tall and slender, almost delicate, and he lacked the easy manner of the police who played craps in the shadow of the courthouse. He wore penny loafers in a city where most people wore boots, and he had a certain stiffness, as if he were a substitute teacher who feared he might lose control of his class.

Unlike his FBI predecessor, who, according to the agency’s own affidavit and informants, had allegedly consorted with gangsters and was later appointed Youngstown’s chief of police at the Mafia’s behest, Kroner was hostile to the local dons. Prickly and shy, he spent hours alone in his small office, smoking cigarettes and listening to intercepted conversations between the different gangs. He made little diagrams of each family, to which he added further details whenever he received a tip from an informant. He did everything he could to bring down their enterprise: tapping their phones, tailing their cars, subpoenaing their friends. In other words, he was, as Strollo and his cronies put it, a “motherfucker.”

One day in the spring of 1981, not long after Charlie the Crab, the head of the Cleveland faction, disappeared without a trace, Kroner searched the apartment of one of the city’s most notorious assassins. The apartment was cluttered with knickknacks, and Kroner and his partner went through each room carefully. In a cabinet, Kroner noticed a bread box and opened it. Inside, tucked amid the stale bread, was an audiotape. When he played it, he heard vaguely familiar voices: “He’s a scared motherfucker.” And: “You either play our fucking game or you[’re] going to be put in a fucking box.” Two of the voices, he was sure, belonged to Charlie and his brother, Orlie the Crab. But there was also another voice, one Kroner thought he recognized from television and radio. Then it dawned on him: It was Youngstown’s newly elected sheriff, a former college football star named James Traficant.

Later, acting on a tip, Kroner and his partner drilled open the Carabbias’ sister’s safe-deposit box, where they found a similar tape with a handwritten note that said: “If I die these tapes go to the FBI in Washington. I feel I have more people after me because of these tapes and ... I pray and ask God to guide and protect my family.” At headquarters, Kroner and his colleagues listened to a jumble of voices arguing about which public officials were allegedly being paid off by the rival Pittsburgh mob.

“You believe they got all them fuckin’ people?” Orlie said.

“I know they got [Mayor] Vukovich,” Traficant said.

“Oh, they definitely got Vukovich,” said Charlie.

“I know they got Leskovansky,” Traficant continued. “I know they got Haynes. I know they got Morley. I know they got Gilmartin.”

“They don’t have Gilmartin,” said Charlie.

Traficant paused, as if running through the names in his mind. “I don’t know all of them,” he finally said. “But I know it’s a fuckin’ fistful.”

With its Pittsburgh rival controlling many of the valley’s politicians, the Cleveland faction knew it needed some pols of its own. And the tapes, apparently made by Charlie the Crab at two meetings during the 1980 sheriff’s campaign, appeared to show them buying Traficant, a rising star. “I am a loyal fucker,” Traficant informs the Carabbia brothers at one point, “and my loyalty is here, and now we’ve gotta set up the business that they’ve run for all these fuckin’ years and swing that business over to you, and that’s what your concern is. That’s why you financed me, and I understand that.”

The arrangement, according to the tapes, was an oldfashioned one: Traficant acknowledged receiving more than $100,000 from the Cleveland faction for his campaign. In exchange, he’d use the sheriff’s office to protect the Carabbias’ rackets while shutting down their rivals. “Your uncle Tony was my goombah...,” said Charlie, “and we feel that you’re like a brother to us.... We don’t want you to make any fuckin’ mistakes.” Traficant assured his benefactors that he was solid and that, if any of his deputies betrayed them, “they’ll fuckin’ come up swimming in [the] Mahoning River.”

But, according to the tapes, Traficant wasn’t primarily worried about his deputies; he was worried about the Pittsburgh mob. As Charlie knew, Traficant had accepted money from Pittsburgh, too—some $60,000, the first installment of which came with the message, “I want you to be my friend.” The young candidate for sheriff was double-crossing the Pittsburgh family (he had just given over at least some of their money to Charlie the Crab to prove his loyalty), and he knew that, when they found out, they would retaliate. “Look, I don’t wanna fuckin’ die in six months, Charlie,” Traficant said.

On the tapes, Kroner and his colleagues could hear Traficant hatching a plan to protect himself from the Pittsburgh Mafia—and the officials they controlled. “Let’s look at it this way, OK?” he said. “They do have the judges.... They can get to the judges and get what they need done.... What they don’t have is the sheriff, and ... I’m one step ahead.” On the day he was sworn into office, Traficant said, he’d take some of the money the Pittsburgh family had given him and use it as evidence to arrest them for bribery. What’s more, he described what he and the Crabs would say if their secret dealings were ever exposed: “I was so fucking pissed off at this crooked government, I came to you and asked you guys if you would assist me to break it up, and you said, `Fuck it ... we’ll do it.’ OK? That’s gonna be what you’re gonna say in court.”

“Orlie too?” asked Charlie. “He’s got a bad heart—”

“Look...,” said Traficant. “I’m not talking fucking daydreams.... If they’re gonna fuck with me, I’m gonna nail them.” Traficant was taken with the audacity of his plan. “If you think about it,” he mused at a later point, “if I fuckin’ did that—”

“You can run for governor,” said Charlie.

They all broke into laughter.

After kroner and his superiors reviewed the tapes, they called Traficant down to headquarters. Kroner had never met the sheriff before, and he watched as he settled into the chair across from him. Traficant was an imposing figure, with wide shoulders and thick brown hair that stuck up on top so that, at first glance, it looked like a wig. You could tell from his muscles that he had once worked in the mills, and he walked as if his joints had been worn down to the bone. As they exchanged pleasantries, Kroner told Traficant he had grown up in Pittsburgh and watched him play football at the university there—where Traficant had starred as a daring quarterback who, as one NFL scout put it, “at the most critical point in a game ... will keep the ball himself and run with it,” bowling over anyone in his path.

What happened next is in dispute. According to sworn court testimony from Kroner and other agents present, Kroner asked the sheriff if he was conducting an investigation into organized crime in the valley. Traficant said he wasn’t. Kroner then asked him if he knew Charlie the Crab or Orlie the Crab. Traficant said he’d only heard of them.

You never met them? Kroner asked.

No, Traficant said.

You never received money from them?

No, he said again.

Then Kroner popped in the tape:

Traficant: “They have given sixty thousand dollars.”

Orlie the Crab: “They gave sixty. What’d we give?”

Traficant: “OK, a hundred and three.”

After only a few seconds, Traficant slumped in his seat. “I don’t want to hear any more,” he said, according to Kroner. “I’ve heard enough.”

In the FBI’s version of events, Traficant acknowledged he’d taken the money, and he agreed to cooperate in exchange for immunity. In front of two witnesses, he then signed a confession that read, in tiny, cursive letters: “During the period of time that I campaigned for sheriff of Mahoning County, Ohio, I accepted money ... with the understanding that certain illegal activities would be allowed to take place in Mahoning County after my election and that as sheriff I would not interfere with those activities.”

According to the FBI, it wasn’t until several weeks later that Traficant recanted his confession, after learning that he would likely have to resign as sheriff and that the reason for his resignation would become public. “Do what you have to do,” he told Kroner, “and I’ll do what I have to do.” Or, as Traficant later told the local TV station, “All those people trying to put me in jail should go fuck themselves.”

The FBI did what it had to first, arresting the 41-year-old sheriff for allegedly taking $163,000 in bribes from the mob and for willfully and knowingly “combin[ing], conspir[ing], confederat[ing], and agree[ing]” with racketeers to commit crimes against the United States. Incredibly, facing up to 23 years in jail, Traficant decided to represent himself in court, even though he wasn’t a lawyer and even after the judge warned him that “almost no one in his right mind” would attempt such a thing.

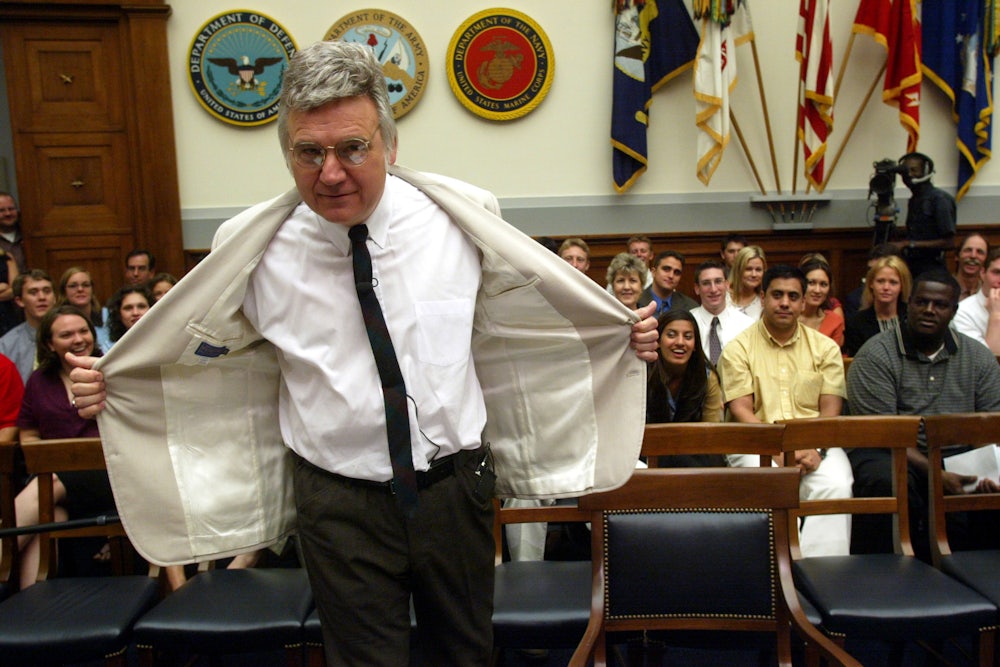

On the day of the trial, pacing the courtroom in a short-sleeved shirt, Traficant told the jury just what he had vowed he would say on the Carabbia tapes: that he was conducting “the most unorthodox sting in the history of Ohio politics.” In a role that he said deserved “an Academy Award,” Traficant told the rapt gallery that he had been acting all along as an undercover agent, trying to convince the Carabbia brothers he was on their side so he could use them to shut down the more powerful Pittsburgh faction. “What I did, and what I set out to do very carefully,” he said, “was to design a plan whereby I would destroy and disrupt the political influence and the mob control over in Mahoning County.”

Though he admitted taking money from the mob, Traficant said he did so only so that his opponent in the campaign wouldn’t get it. And, though he acknowledged that his voice was on the tapes, he claimed they were doctored to incriminate him. And, though he agreed he had signed “a statement,” he said it was different from the fraudulent “confession” the FBI introduced into evidence. And, though he confessed he had initially lied to the FBI about the sting, he said it was only because he couldn’t trust its agents—one of whom, back in the ‘60s, was allegedly tied to the mob. Indeed, he insisted that, if the FBI hadn’t intervened, he would have cleansed the most corrupt county in the country. “The point of the matter I want to make is this,” he said. “I got inside of the mob.” Then: “I fucked the mob.”

It was a stunning performance. When Kroner finally took the stand and testified that he had seen Traficant sign the confession, the sheriff jumped out of his chair and yelled, “That’s a goddamn lie!” During cross-examination he taunted his FBI adversary, saying, “Oh, I see” and “No, Bob.” Half crazy, half charming, he referred to himself as “my client” and asked reporters, “How am I doin’?” In a region instinctively wary of outsiders, he became, by the end of his defense, an emblem of the valley. In Youngstown, people held parties on his behalf. His supporters sold t-shirts touting his heroic struggle. It didn’t matter that the IRS would later find Traficant liable for taking bribes and evading taxes, in a civil trial in which he took the Fifth. Or that the money he had allegedly taken as evidence for the sting was never turned over. Or that one of his deputies claimed on the stand that Traficant had repeatedly asked the deputy to shoot him to make it look like an attempted mob hit. Traficant understood his community better than anyone else. It took a jury four days to decide to acquit. Charlie the Crab was wrong about only one thing: Traficant wouldn’t become governor. He would become a United States congressman.

By the time Traficant went to Washington, D.C., in 1985, the valley was already disintegrating. The worldwide demand for steel had plummeted, plunging the area into near-permanent recession. Mills barricaded their doors. Department stores closed. At least one airline discontinued its service to the region. By the end of the decade, the population in Youngstown alone had fallen by more than 28,000, while the sky, leaden for half a century, turned almost blue.

Traficant, reelected to term after term in Congress, railed against the closings, sometimes even sounding a little like Charlie the Crab. When one of the last steel mills in the region filed for bankruptcy in the late ‘80s, Traficant warned: “I think this is beyond all this talking phase. If [the owner] rips off the last industrial facility ... then someone should grab him by the throat and stretch him a couple of inches.” But there was nothing he or anyone else could do.

And if prosperity had brought the mob to the valley a half-century earlier, depression cemented its rule. The professional classes that did so much to break the culture of the Mafia in Chicago and Buffalo and New York in the 1970s and ‘80s practically ceased to exist in Youngstown. Much of the valley’s middle class either left or stopped being middle-class. And so Youngstown experienced a version of what sociologists have described in the inner city. The city lost its civic backbone—its doctors and lawyers and accountants. The few upstanding civic leaders who remained were marginalized or cowed. Hierarchies of status and success and moral value became inverted. The result was a generation of Batchos, kids who worshiped the dons the way other children worshiped Mickey Mantle or Joe DiMaggio. (Batcho even tattooed a picture of a legendary mob boss on his left upper arm, telling people proudly, “[I’d] take a bullet for him.”) Meanwhile, Lenny Strollo and his partners, in need of players for their cash-strapped casinos, began catering to the local drug dealers and criminals, who were the only people left with money to spend.

The mob, which had once competed with the valley’s civil society, largely became its civil society. As late as 1997, in the small city of Campbell, Strollo controlled at least 90 percent of the appointments to the police department. He fixed the civil-service exam so he could pick the chief of police and nearly all the patrolmen. The city law director literally brought the list of candidates for promotion to Strollo’s house so the don could select the ones he wanted. “Strollo,” says an attorney familiar with the city, could “determine which murderers went to jail and which ones went free.”

In 1996, while three mob hit men, including Mo Man Harris, were on their way to kill their latest target, they were pulled over by the Campbell police for speeding, according to people in the car. In the vehicle the cops found an AK-47 rifle, a .357 Magnum revolver, and a 9 mm pistol. One of the killers used his cell phone to call Jeff Riddle, who rushed to the scene and told the police the men were running an errand for Bernie the Jew. The cops let them go.

In the rare instances when the police arrested a reputed mobster, Strollo and his associates simply paid off the judges. There was such a sense of impunity that once in the spring of 1996, when an incorruptible judge prevented Strollo from fixing a particular assault case, he dispatched Batcho with a walkie-talkie and a silencer to wound the defense attorney so they could get a mistrial. “I said, `Are you attorney Gary Van Brocklin?’” Batcho later recalled. “And he said, `Yes, I am.’ ... And I shot him right in the knee.” “I don’t know how an honest defense attorney could make a living in this town,” says Kroner’s boss, Andy Arena.

And, of course, Strollo’s tentacles reached the valley’s representative in Congress as well. Until he was exposed in 1998, Traficant’s top aide in the district, Charles O’Nesti, served as the “bagman” between Strollo and the city’s corrupt public officials. (Traficant had hired O’Nesti in 1984, despite his claims on the infamous tapes that O’Nesti was a mob crony whom he would arrest as part his so-called sting to clean up the valley.) While working for Traficant, O’Nesti would meet Strollo at the don’s farm or talk with him on the phone. The two even conspired to steal a stretch of city pavement as it was being laid down. “The hold that the mob has had here to this day,” says Arena, “I don’t think you’ll see anywhere else in the United States.”

The FBI sting that would start unraveling this web of corruption began in 1994. Kroner, now middle-aged, had given up smoking through hypnotism and put several pounds on his slender frame. One morning, as he met with other agents in their cramped office in nearby Boardman Township, he could barely contain his frustration. He had just witnessed the disintegration of one of his few triumphs: 14 months after he’d nailed Strollo for gambling, his nemesis had reemerged from prison and reasserted his power. Even when we bust them, Kroner thought, they just come back.

So, after years of disappointment, Kroner and his colleagues opted for a new approach: rather than attack the mob from the top, as they had in the past, they’d start at the bottom, with the number runners and the stick handlers at the Barbut games. The investigation was based on the theory of carpenter ants—if you didn’t eliminate all of them, even the smallest ones, they would simply multiply again. “We set forth right in the beginning that we were not going to stop until we got to the nest,” says Kroner, “and if it meant having to work deals with people we had lots of evidence against, that’s what we were going to do if it would lead us up the chain.”

One of the first people they persuaded to cooperate was a local bookie named Michael Sabella, who worked in the markets and always smelled of fish. After being questioned by the feds on another matter, he agreed to wear a wire around the county’s gambling dens. Eventually, he gave them enough evidence to get wiretaps on several low-level members of Strollo’s sprawling enterprise, who, in turn, gave them enough evidence to tap more phones, and so on. As the number of intercepted conversations mushroomed into the thousands, Kroner and his partners, John Stoll and Gordon Klau, spent days sifting through transcripts.

But, after more than a year of sleepless nights, they still hadn’t penetrated the Mafia’s innermost circle. Hoping to “shake the tree,” as Kroner put it, they started raiding gambling joints, which finally gave them enough evidence to install bugs in Strollo’s kitchen and telephones. They began picking up snippets of incriminating conversations. They heard what sounded like a plot to shake down a priest and what some “asshole did before ... he got whacked.”

At one point early in their investigation, Kroner got a tip from an informant that Strollo was going to kill one of his rivals, Ernie Biondillo. Feeling a moral obligation to warn Biondillo, he picked up the phone and called him. “This is Bob Kroner,” he said. “You know who I am?”

“Yeah, I know who you are.”

“Well, I need to sit down and talk to you alone.”

They met that night in a parking lot. Kroner hoped the warning would encourage Biondillo to cooperate with the investigation. But Biondillo just kept saying, Who the fuck wants to kill me?

Kroner studied him hard. “I can’t tell you that. I’m not out here to start a war.”

Unable to get an answer, Biondillo drove off in his Cadillac. Several months later, as Biondillo turned down a deserted street, two cars boxed him in, and two men wearing rubber masks opened fire. By the time Kroner got to the hospital, Biondillo was already dead.

Though Kroner was sure the hit was ordered by Strollo, the FBI still didn’t have enough evidence to arrest him. But, by the summer of 1996, the authorities were finally starting to close in, and Strollo, sensing it, became more and more paranoid. On the phone, he began speaking almost exclusively in code and, suspecting Kroner was listening in, would say, “Bob, can you hear me? Can you hear me?” Once, upon meeting one of his oldest and most trusted confidants, Strollo had a sudden premonition that the friend was wearing a wire. Another time he decided a plane was following one of his bookies. When someone tried to calm him down, he snapped: “This is my life you’re talking about ... I got to fight for survival.”

Strollo grew obsessed with Kroner. He sent one of his men to find out if the FBI agent’s father, an old-fashioned city cop, could be paid off to control his renegade son. But word came back that the father was honest, like his kid. Knowing the FBI was tapping him, Strollo began to plant evidence against his nemesis to suggest Kroner was on the take. He told associates, almost nonchalantly, that Kroner had received bribes from “Little Joey” and was running drugs through the valley.

Then one day Kroner’s partner heard Strollo grow more and more menacing. “I don’t know what I’m going to have to do about these guys,” he said, referring to the FBI agents. Not long afterward, unbeknownst to the FBI, Strollo ordered the hit on Gains, the county prosecutor who, the Mafia believed, was about to hire Kroner as his chief investigator.

But the bungled hit, of course, only created a bigger problem: In spring 1997, Gains received the phone call fingering the hapless assassins. On the basis of information from the caller—”the scorned woman,” as Kroner gratefully called her—Bernie the Jew, Riddle, and Harris were all charged with attempted murder. One day, as Batcho was leaving his house with a friend to go to Jay’s Hot Dogs, an unmarked car pulled up behind him. “Are you Mark Batcho?” two men said, jumping out of their car. “No, I’m not Mark Batcho. I don’t know him,” Batcho replied. But, in spite of his protestations, they took him into custody, where he eventually became, as he put it, “the lowest form of life there [is]—a mob rat.”

On a cold morning just before Christmas 1997, dozens of FBI agents fanned out through the valley, arresting more than 28 other mob associates. When Kroner showed up at Strollo’s door with an arrest warrant, Strollo said, “Are you happy now, Bob?”

In the end, nearly all of Strollo’s underlings pleaded guilty and turned evidence against one another, except for Bernie the Jew and Riddle, the two men who had adopted the old Sicilian code even though they could never be officially inducted. “The only ones who had any balls were a shvartsa and a shine,” said one of the lawyers familiar with the case.

Bernie insisted there was nothing to worry about: Strollo would never turn on them and break his oath of silence. But just before the trial, even as Bernie was speaking, Strollo’s lawyer was leading his client upstairs, where he cut his final deal with the prosecution and told Kroner, “You win.”

The announcement is surely one of the strangest moments in c-span’s history: “I will probably be under indictment” in the next few months, Traficant says, staring into the camera. It is March 2000, almost 20 years since his last arrest. The congressman has put on a somber black coat and tie for the occasion, but his hair is slightly tousled and his trademark long sideburns make him look like an aging biker. In his 16 years in Congress, Traficant has earned a reputation as a fiery, eccentric populist who often appears on the House floor, in polyester suits, to champion the working class and rail against the IRS. In a city without memory he has become known simply as “the honorable gentleman from Ohio,” an almost cultish figure who sleeps in his office to save money and closes his speeches with the line “Beam me up, Mr. Speaker.”

But today he looks as if he hasn’t slept in weeks, and he says he’s scared to death. “Hawks are circling, buzzards [are] circling, sharks [are] circling ... trying to kill the Traficant election,” he stammers. He pauses, his cheeks flushed. “Let me tell you what: Twenty years ago—not quite—I was the only American in the history of the United States to defeat the Justice Department.... They have targeted me ever since.” Suddenly he points his finger into the camera: “I’m targeting them. They better not make a damn mistake ... I am mad and ... I’m going to fight like a junkyard dog in the face of a hurricane, and ... if I beat them you’re now watching one of the richest men in America, because I’m going to sue their assets all apart.”

Even stranger than his warnings to the Justice Department and the FBI—and his admonition that he’ll shoot any unexpected late-night visitors to his house—are Traficant’s threats to his own party. He warns that if Democratic leaders don’t stand by him, he’ll switch parties—a critical defection that could undermine the Democrats’ chances of regaining a House majority this fall. And, as further compensation for his loyalty, Traficant demands a list of favors for his district: “I want an empowerment zone from the president of the United States—and I expect it this year—and I want additional appropriations....” On national television, he seems to be extorting his own party.

Traficant doesn’t say what the indictment will be for; nor will the FBI. But his c-span announcement comes on the heels of a six-year investigation into organized crime in the Mahoning Valley that has already led to convictions against Traficant’s former aide O’Nesti, a disbarred attorney who had advised him for several years, and a former deputy in his sheriff’s office. According to news accounts first detailed in the Youngstown Vindicator and the Cleveland Plain Dealer, investigators are looking into, among other things, whether the congressman received illegal contributions—including the use of a Corvette—from associates in the valley. They have recently homed in on two brothers, Robert T. and Anthony R. Bucci, who own a paving company in Traficant’s district and allegedly delivered materials and did construction work on the congressman’s 76-acre farm. Both brothers appear deeply enmeshed in the city’s network of corruption. On one of the FBI’s wiretaps, O’Nesti conspires with Strollo to steer a million-dollar contract to the Buccis’ company. Robert Bucci has since apparently fled the country after allegedly transferring millions of dollars to an offshore account on the Cayman Islands.

Through it all, Traficant has steadfastly maintained his innocence, and the valley is bracing for a second showdown. “Here’s what I’m saying now,” he insists grimly on c-span, “and I’m saying this to the Justice Department in Cleveland, Ohio.... If you are to indict me, indict me in June so I can be tried over the August recess, [because] I don’t want to miss any votes.”

When I arrive in Youngstown on a recent, cold spring morning, there is an odd sense of deja vu, as if the old tapes have been rewound and played again. As Traficant campaigns for a ninth term in Congress, he once again faces the old accusations: bagmen, illicit favors, payoffs. I head downtown, trying to find someone to ask about the allegations, but the city is bizarrely empty, as if people had been called away on a last-minute errand and never came back. Finally, after rows and rows of boarded-up stores and deserted sidewalks, I see a light in one of the shops. In the window, Italian suits hang with handkerchiefs in the pockets. An old man is folding clothes by the cash register. When I ask him about Traficant, he stiffens. “Ain’t no one gonna get rid of Traficant,” he says. “Traficant’s too sharp.” Far from being angry about the city’s history of corruption, he seems almost proud of it. He recalls fondly the “henchmen,” including Strollo, who bought their suits from him. “They didn’t wear red or pink [ones] like they’re coming out with now,” he says. When I press him about the local corruption, he shrugs. “Who cares? If you’re working and making a living and nobody is bothering you, why are you going to butt in?”

Later, at my hotel, several elderly men are sitting around a table arguing about Traficant. “Traficant produces,” says one. “That’s what counts.” “Damn right!” says another. They are all in their seventies and eighties and have lived in the valley for decades.

“When I was eight years old,” one of them says suddenly to me, as if to make a special point, “I delivered newspapers downtown, and I would always go by this speakeasy on Sunday afternoon. Well, one day the owner says, `I want you to meet someone.’ So I went over and it was Al Capone.” He pauses, shaking his head in awe. “Al Capone.”

“You see this,” another man says, referring to the last speaker. “This is typical Youngstown. Here’s an educated man, an attorney, and Traficant is a god of his, and he’s still raving about meeting Al Capone.”

When I stop at Youngstown State University to talk to Mark Shutes, an anthropologist and one of the only academics who studies the region, the first thing he says is, “You’re not gonna write some crap about how we’re all victims of gangsters, are you?” Shutes contends that, after so many years of eroded civic institutions, the community has come to rely increasingly on mobsters, who play the same role in civic life that the police and the political establishment do in other cities. “We have socialized ourselves and our offspring that this is the way the world is,” he says. “This is our little safe part, with our community and church, but in order for it to be safe, you need these people to be brokers.” Indeed, in a world where corruption is normal, he says, values prized in other cities are, in the valley, deemed counterproductive. “We don’t see high ideals as being a benefit,” he explains. “We see [them] as being a weakness. There is no sense in this community in which gangsters are people who have imposed their will on our community. Their values are our values.”

So much so that, despite two opponents railing against his alleged mob ties and an FBI investigation reportedly closing in on him, Traficant won the March 7 Democratic primary with more votes than his two main competitors combined. Traficant seems so unbeatable in November that some congressional Republicans have decided to defend him, apparently hoping he’ll follow through on his threat to switch parties and cement their fragile majority. “Jimmy Traficant is not being done right by,” Republican Representative Steve LaTourette of Ohio told the Cleveland Plain Dealer. “There isn’t a finer man, there isn’t a finer member of Congress, there isn’t a finer human being ... than Jim Traficant. God bless you, Jimmy Traficant, and I hope to serve with you for many years.”

Emboldened by his popular support, Traficant is doing what he’s long done so well: rallying the valley against the outsiders trying to besmirch its name. Over the last year, he has defiantly called his convicted former top aide, O’Nesti, a “good friend” and championed a local sheriff convicted of racketeering, arguing that he should be moved to a prison closer to Youngstown to be near his ill mother. “[T]hese sons of bachelors will not intimidate me,” he likes to say of the FBI, “and they won’t jack me around.”

Though he has retreated from reporters—”I’ll only make an official statement when I’m actually killed,” he says— the press releases have begun to pour out of his Washington office: “traficant bill would create new agency to investigate justice department”; “traficant wants president to investigate federal agents in youngstown.” On the House floor, where his speech is protected against suits for libel, he is bolder still: “Mr. Speaker, I have evidence that certain FBI agents in Youngstown, Ohio, have violated the rico statute and ... stole large sums of cash.... What is even worse, they `suggested’ to one of their field operative informants that he should commit murder. Mr. Speaker, murder.”

At FBI headquarters in Boardman, Kroner and his boss, Andy Arena, are trying to fend off Traficant’s allegations. They are careful not to say anything about the press releases, the pending investigation of the congressman, or even the 1983 trial. But it is clear they are under siege. On talk radio, Traficant supporters denounce Kroner as a thief, a con man, a crook, a creep, a liar, and a dope dealer. “The thing that most depressed me,” says Kroner, “was when I became the subject on talk radio one day and they were discussing my integrity.” He folds his arms. “I just have to block out [those] things.” Rather than a hero, he has become almost a pariah. “Everything is turned upside down here,” says Arena.

As Kroner sits in his neatly pressed jacket and loafers, his 20-year-anniversary FBI medallion mounted prominently on a thick gold ring, he seems slightly defensive. “Every time we charge another public official, the [media] presents it as another black eye for the community,” he says. “I’d prefer if they’d portray it to the community as another step in cleansing ourselves. We’ve got to take a look at what’s being done here as a positive thing.”

It is dusk by the time he shows me around the valley, and we rush past the old steel mills, past the Greek Coffee House and the Doll House and all the other gambling dens, past the place where Bernie the Jew met with his team of hit men and where Strollo had Ernie Biondillo whacked in broad daylight. “We’re a part of this community like everyone else,” Kroner says at one point. “We suffer the same problems if we live in a corrupt town.” He pauses for a moment, perhaps because he can’t think of anything to say or perhaps because he’s not able to talk about the expected Traficant indictment or perhaps because he realizes that, after 25 years in the Mahoning Valley, he’s done all he can do. “As long as they choose to put people in office who are corrupt,” he says, “nothing will ever change.”