Senator George Allen is the only person in Virginia who wears cowboy boots. It’s a warm and bright spring day in the swampy southeastern Virginia town of Wakefield, site of the annual Virginia political fest known as Shad Planking. Once a whites-only event where state Democrats picked their nominees, Shad Planking is now a multiracial affair where candidates from both parties come to show off their regular-guy bona fides and trade lighthearted barbs. Beer flows freely. Knots of tailgaters gossip about state politics. In a clearing amid tall pines, shad is cooked on long wooden boards. Though the two Democrats fighting for a shot to challenge Allen this year in his Senate reelection campaign both show up for the event, Allen clearly owns the crowd, as the sea of royal blue ALLEN T-shirts and baseball caps makes clear. The senator has emerged as the principal conservative alternative to John McCain in the early jockeying among 2008 Republican presidential candidates, and today’s event is a reminder of what conservatives love about him.

But nobody else wears cowboy boots. The guy passing out the stickers that say I SUPPORT CONFEDERATE HISTORY MONTH is in sneakers. The libertarian who asks me to ask Allen about industrial hemp and abolition of the IRS is in very sensible shoes. The pink and pudgy sports-radio host drawling friendly questions at Allen is in loafers. A guy walks up to Allen and sticks a piece of paper in his hand. “Some people are handing out these, saying you aren’t pro-gun enough,” he tells the senator, a little menacingly. I look down at his feet. High-tops.

There is a guy in a bolo tie. This excites Allen, who is quoted in the newspaper the next day approvingly advising bolo guy, “If you’re going to wear a tie, that’s the one to wear.” Allen has lots of finely honed opinions about red-state cultural aesthetics, and he is always eager to share them. He talks with the radio host about the merits of Virginia’s different country music stations. Allen is dismayed about the modern country played on one AM station. “I like the real country music,” he says.

It’s credible enthusiasm given that, this afternoon, Allen resembles a froufrou version of Toby Keith. He is wearing a blue button-down shirt and brown pants accented with a fat brass belt buckle that says VIRGINIA in stylized, countrified letters. And, of course, he’s wearing the cowboy boots. They are black, broken in, and vaguely reptilian. From his back pocket, he removes a tin of Copenhagen—”the brand of choice for adult consumers who identify with its rugged, individual and uncompromising image,” according to the company—and taps a fat wad of the tobacco between his lip and gum using an impressive one-handed maneuver. As the scrum breaks up, Allen turns away and spits a long brown streak of saliva into the dirt, just missing one of his constituents, a carefully put-together, blonde, ponytailed woman approaching the senator for an autograph. She stops in her tracks and stares with disgust at the bubbly tobacco juice that almost landed on her feet. Without missing a beat, Allen’s communications director, John Reid, reassures her: “That’s just authenticity!”

It’s a word they use a lot it the Allen world—”authenticity.” His aides and the growing ranks of conservative backers hungry for someone to take out McCain emphasize Allen’s down-home credentials and cowboy-boot charisma far more than his voting record. A glowing National Review cover story, to take one recent example, trumpeted Allen’s preternatural fluency in the sports metaphor- laden language of American masculinity. This gift for communicating in the vernacular of John Madden doesn’t just distinguish him; it makes him the ideal vehicle for a particular brand of Republican campaign strategy. As the GOP has grown increasingly adept at turning elections into contests about style and character rather than issues and ideas, some Republicans have become obsessed with finding candidates who can project the cultural identity of a red-state everyman. It sometimes seems that pro-NASCAR has replaced pro-life as the party’s litmus test.

While Allen’s shit-kickin’ image may be the subject of certain Republican consultant fantasies, it may not be ideal in the current political climate. A certain someone has, after all, used that shtick before, effectively bludgeoning his Democratic opponents with his Texas brand of cultural populism. But, by now, that folksy act looks a little spent. And, although Allen is undoubtedly the hot new thing within the Beltway’s conservative establishment, some denizens of K Street and right-wing newsrooms have begun doubting whether he represents their best hope to snuff out the burgeoning campaign of their enemy, McCain. “If my choice is, ‘Who do I want to go out with to a fun dinner to drink our brains out,’” says one of the party’s top fund-raisers who has met with Allen many times, “there’s no question, it’d be Allen. He’s a guy’s guy, but he didn’t blow me away in terms of substance.”

Fortunately for Allen, he has a protean ability to shift political personas to adapt to the prevailing political fashions. In the 1980s, he was a Reagan revolutionary. As governor of Virginia at the height of the Gingrich insurgency, he promoted his own version of the Contract with America throughout his state. As Virginia modernized, with high-tech eclipsing the tobacco economy, he remade himself as a traveling-salesman governor, luring new companies to the state.

Even in these early days of his budding presidential campaign, he has slipped out of the self-styled image of Bush’s most loyal foot soldier. He now says the president is welcome to campaign for him but expresses no enthusiasm for the idea. He tells reporters he is more like Ronald Reagan than George W. Bush. But it’s not Bush from whom Allen ultimately needs to distance himself. There is a graveyard of old Allen personas—unpresidential personas, downright ugly ones—that could threaten his political ascendance. Even his authentic self—or, rather, the man described by his own family—might prove just as great a liability. His identity crisis has created the most intriguing duel of 2008: Before he runs for president, George Allen has to run against himself.

It’s mid-April, and the private plane carrying Allen and his entourage has just landed at the Stafford Regional Airport. After months of out-of-state fundraising and sojourns into Iowa and New Hampshire, the senator is suddenly taking care of business back home with a three-day, eleven-city reelection announcement tour. Jim Webb, Reagan’s Navy secretary, is running in the Democratic primary, Bush’s job approval rating in the state is in the 30s, and there is some cautious talk about Virginia, once a presumed gimme for Allen, becoming a competitive race.

After all the heady presidential planning—the hiring of big-name consultants like Mary Matalin, Ed Gillespie, and Dick Wadhams and the first-place finish in fund-raising last quarter—nothing could bring Allen down to earth faster than the Stafford event. There are less than three dozen people here, including numerous Allen aides. The wind knocks over the American and Virginia flags that form Allen’s backdrop. And then there is Craig Ennis, who says he’s an independent candidate here to debate Allen. His T-shirt says U.S. SPECIAL FORCES: MOTIVATED, DEDICATED, LETHAL. He positions himself in front of the platform on which Allen and his wife, Susan, stand and holds a homemade sign: why do you hide from me?

Allen delivers a stump speech that rests heavily on his record as governor from 1994 to 1998 and skips rapidly over the details of his five years in the Senate. The soft-peddling of his legislative record may have struck the audience as a strange tack for an incumbent. But it has its own compelling political logic. Allen knows that senators have a dismal record as presidential candidates. There is, however, an equally compelling reason why Allen might not want to revisit his years in Richmond.

In the early ‘90s, Allen exuded the revolutionary spirit of the Republican insurgency. His 1994 inaugural address as governor promised to “fight the beast of tyranny and oppression that our federal government has become.” That year, he also endorsed Oliver North for the Senate even as Virginia Senator John Warner and others in the party establishment shunned the convicted felon. At North’s nominating convention, Allen proposed a somewhat overwrought approach for beating Democrats: “My friends—and I say this figuratively—let’s enjoy knocking their soft teeth down their whining throats.”

But, while Allen may have genuflected in the direction of Gingrich, he also showed a touch of Strom Thurmond. Campaigning for governor in 1993, he admitted to prominently displaying a Confederate flag in his living room. He said it was part of a flag collection—and had been removed at the start of his gubernatorial bid. When it was learned that he kept a noose hanging on a ficus tree in his law office, he said it was part of a Western memorabilia collection. These explanations may be sincere. But, as a chief executive, he also compiled a controversial record on race. In 1994, he said he would accept an honorary membership at a Richmond social club with a well-known history of discrimination—an invitation that the three previous governors had refused. After an outcry, Allen rejected the offer. He replaced the only black member of the University of Virginia (UVA) Board of Visitors with a white one. He issued a proclamation drafted by the Sons of Confederate Veterans declaring April Confederate History and Heritage Month. The text celebrated Dixie’s “four-year struggle for independence and sovereign rights.” There was no mention of slavery. After some of the early flaps, a headline in The Washington Post read, “GOVERNOR SEEN LEADING VA. BACK IN TIME.”

Allen has described those early years as a learning experience. Indeed, he sanded off the rough edges and began molding himself to the Bush era, when conservatives began abandoning the crudeness of their old Southern strategy. During the second half of his gubernatorial term, Allen began positioning himself as the next cool thing in Republican politics, a governor more interested in results than partisanship. Indeed, at the Stafford Airport stump speech, there are no confederate flags or coded racial appeals. Instead, Allen talks about energy independence and the competitive challenge from rising economies like China’s and India’s. If it weren’t for some of the rhetoric about “tax commissars,” one might mistake Allen’s stump speech for a Tom Friedman column.

Even if the moderate turn leads voters to remember the governor of fiscal responsibility rather than the Confederate history booster, there’s still a problem. Before there was a Governor Allen, there was a state legislator Allen. Allen became active in Virginia politics in the mid-’70s, when state Republicans were first learning how to assemble a new political coalition by wooing white Democrats with appeals to states’ rights and respect for Dixie heritage.

Allen was a quick study. In his first race in 1979—according to Larry Sabato, a UVA professor and college classmate of Allen’s—he ran a radio ad decrying a congressional redistricting plan whose main purpose was to elect Virginia’s first post-Reconstruction black congressman. Allen lost that race but was back in 1982 and won the seat by 25 votes. He spent the next nine years in Richmond, where his pet issues, judging by the bills he personally sponsored, were crime and welfare. But he also found himself repeatedly voting in the minority on a series of racial issues that he seems embarrassed by today. In 1984, he was one of 27 House members to vote against a state holiday commemorating Martin Luther King Jr. The Richmond Times-Dispatch reported, “Allen said the state shouldn’t honor a non-Virginian with his own holiday.” He was also bothered by the fact that the proposed holiday would fall on the day set aside in Virginia to honor Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. That same year, he did feel the urge to honor one of Virginia’s own. He co-sponsored a resolution expressing “regret and sorrow upon the loss” of William Munford Tuck, a politician who opposed every piece of civil rights legislation while in Congress during the 1950s and 1960s and promised “massive resistance” to the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision banning segregation.

None of this means Allen is a racist, of course. He is certainly not the same guy today that he was in the ‘80s. But his interest in Southern heritage and his fetish for country culture goes back even further. And what’s truly improbable is how someone with his upbringing ever acquired such backwoods tastes.

George Allen is the oldest child of legendary football coach George Herbert Allen, and, when his father was on the road, young George often acted as a surrogate dad to his siblings. According to his sister Jennifer, he was particularly strict about bedtimes. One night, his brother Bruce stayed up past his bedtime. George threw him through a sliding glass door. For the same offense, on a different occasion, George tackled his brother Gregory and broke his collarbone. When Jennifer broke her bedtime curfew, George dragged her upstairs by her hair.

George tormented Jennifer enough that, when she grew up, she wrote a memoir of what it was like living in the Allen family. In one sense, the book, Fifth Quarter, from which these details are culled, is unprecedented. No modern presidential candidate has ever had such a harsh and personal account of his life delivered to the public by a close family member. The book paints Allen as a cartoonishly sadistic older brother who holds Jennifer by her feet over Niagara Falls on a family trip (instilling in her a lifelong fear of heights) and slams a pool cue into her new boyfriend’s head. “George hoped someday to become a dentist,” she writes. “George said he saw dentistry as a perfect profession—getting paid to make people suffer.”

Whuppin’ his siblings might have been a natural prelude to Confederate sympathies and noose-collecting if Allen had grown up in, say, a shack in Alabama. But what is most puzzling about Allen’s interest in the old Confederacy is that he didn’t grow up in the South. Like a military brat, Allen hopscotched around the country on a route set by his father’s coaching career. The son was born in Whittier, California, in 1952 (Whittier College Poets), moved to the suburbs of Chicago for eight years (the Bears), and arrived in Southern California as a teenager (the Rams). In Palos Verdes, an exclusive cliffside community, he lived in a palatial home with sweeping views of downtown Los Angeles and the Santa Monica basin. It had handmade Italian tiles and staircases that his eccentric mother, Etty, designed to match those in the Louvre. “It looks like a French chateau,” says Linda Hurt Germany, a high school classmate.

Even the elder George Allen wasn’t Southern—he grew up in the Midwest—but the oddest part of the myth of George Allen’s Dixie rusticity is his mother. Rather than a Southern belle, Etty was, in fact, French, and, as such, she was a deliciously indiscreet cultural libertine. She would do housework in her bra and panties. She wore muumuus and wraparound sunglasses and once won a belly button contest. According to Jennifer, “Mom prided herself for being un-American…. She was ashamed that she had given up her French citizenship to become a citizen of a country she deemed infantile.” When her husband later moved the family to Virginia, Etty despised living in the state. She was also anti-Washington before her son ever was, albeit in a slightly more continental fashion. “Washingtonians think their town resembles Paris,” she once scoffed. “If Paris passed gas, you’d have Washington.”

Allen is now so associated with football—he played at Palos Verdes High School and at UVA, speaks in famously complicated football metaphors, and frequently tosses around the pigskin at campaign events—that he is most often described in relation to his father. But his siblings have said he actually takes after mom. Like Etty, George saw himself as disconnected from the culture in which he lived. He hated California and, while there, became obsessed with the supposed authenticity of rural life—or at least what he imagined it to be from episodes of “Hee Haw,” his favorite TV show, or family vacations in Mexico, where he rode horses. Perhaps because of his peripatetic childhood, the South’s deeply rooted culture attracted him. Or perhaps it was a romance with the masculinity and violence of that culture; his father, who was not one to spare the rod, once broke his son Gregory’s nose in a fight. Whatever it was, Allen got his first pair of those now-iconic cowboy boots from one of his father’s players on the Rams who received them as a promotional freebie. He also learned to dip from his dad’s players. At school, he started to wear an Australian bush hat, complete with a dangling chin strap and the left brim snapped up. He wore the hat for a yearbook photo of the falconry club. His favorite record was Johnny Cash’s At Folsom Prison. Writing of her brother’s love for the “big, slow-witted Junior” on “Hee Haw,” Jennifer reports, “[t]here was also something mildly country-thuggish about Junior that I think George felt akin to.”

In high school, Allen’s “Hee Haw” persona made him a polarizing figure. “He rode a little red Mustang around with a Confederate flag plate on the front,” says Patrick Campbell, an old classmate, who now works for the Public Works Department in Manhattan Beach, California. “I mean, it was absurd-looking in our neighborhood.” Hurt Germany, who now lives in Paso Robles, California, explodes with anger at the mention of Allen’s name. “The guy is horrible,” she complains. “He drove around with a Confederate flag on his Mustang. I can’t believe he’s going to run for president.” Another classmate, who asks that I not use her name, also remembers Allen’s obsession with Dixie: “My impression is that he was a rebel. He plastered the school with Confederate flags.”

Politically, Allen’s years in Palos Verdes were dominated by the lingering racial tensions from the riots in nearby Watts in 1965—when that neighborhood was practically burned to the ground—and the nationwide riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, which left other parts of Southern California in flames. It is with that context in mind that four former classmates and one former administrator at Allen’s high school described to me an event for which Allen is most remembered—and the first glimpse that the chateau-raised Californian might grow up to become a defender of the South’s heritage.

It was the night before a major basketball game with Morningside High. The mostly black inner-city school adjacent to Watts was coming to the almost entirely white Palos Verdes High to play. When students arrived at school on game day, they found graffiti spray-painted on the school library and other places. All five people who described the incident say the graffiti was racially tinged and meant to look like the handiwork of the black Morningside students. But it was actually put there by Allen and some of his friends. “It was something like DIE WHITEY,” says Campbell. The school administrator, who says he is a Republican and would “seriously consider” voting for Allen for president, says the graffiti said, “BURN, BABY, BURN,” a reference to the race riots.

Soon after, Allen finally got the chance to become a Southerner. In 1971, his dad was hired to coach the Redskins, and the Allens relocated to Virginia. Allen transferred from UCLA, where he spent his first year of college, to UVA. The old “Hee Haw” fan was like a pig in slop. Even at Virginia’s own state school, Allen stood out for his showy brand of good ol’ boyness. Under the headline “ALLEN AND COUNTRY LIVING,” a 1973 profile in the school paper noted his penchant for country music had earned him the campus nickname of “Neck.” He drove a pickup truck (paid for by the Redskins). He wore cowboy boots. He supported Richard Nixon and the war in Vietnam. He once shot a squirrel on campus, skinned it, ate it, and hung its pelt on his wall. “He was trying to be more Virginian than the average Virginian,” says Sabato.

After graduating, Allen stuck around UVA for three years of law school. Professors remember him as the guy in the back row of class spitting tobacco into a cup. “He was Mr. Cool,” says a UVA law professor who taught him. “But, if you would have said he would go on to be governor, senator, and then run for president, people would have said that was the least probable thing that would ever happen.”

I am standing in front of George Allen, but he doesn’t seem to notice me. He’s seated behind a tank-sized wooden desk in his Senate office, buried in paperwork. In front of him is a white spit cup, the outside of it stained a little brown by some errant saliva. Though I’ve been announced and walked the length of his football field of an office to greet him, he is distracted. I stand for an awkward moment before he finally bounds out of his chair, opening up his six-foot-four frame—perhaps five with cowboy-boot heels—and welcomes me with a hearty shake and a tobacco-specked smile.

His office might be called classically senatorial. In the reception area, there are three walls of power photos, political cartoons, and action shots of Allen. There’s Allen driving a race car. Allen on a horse. Allen throwing a football. A cover story from Richmond magazine features his wife: “WHAT VIPS DRIVE—FIRST LADY SUSAN ALLEN ♥ HER 4WD.”

Allen and I talk a little about being a senator versus a governor. He seems determined to keep his outsider cred in hopes of surviving the anti-incumbent wave building in Virginia. He casts his lot in with the angry voters. “I’m aggravated,” he says. “I get frustrated by the slow pace of the Senate, as are most Virginians and most Americans. I like action. I like to see things get done.”

But, mostly, Allen and I talk about race. It’s a subject that’s much on his mind these days, as he tries to make amends for his old pro-Dixie stances. He’s trying to get more money for historically black colleges. And he has spent the last few years in what might be called civil rights boot camp. In 2003, he traveled to Birmingham, Alabama, on a “civil rights pilgrimage.” “I wish I had [gone] sooner,” he says. “I was listening to the old civil rights movement, the strategies, the foundations, the tactics, and—in watching all of it, and in my point of view—I don’t see how you can stand being knocked off a stool at a lunch counter and just take it. My reaction is, ‘I don’t see how you can take it.’ And they say, ‘You understand, it’s all peaceful and nonviolent.’ And I say, ‘I just don’t understand this.’” Allen bonded at the event with a former Black Panther who agreed with his take on nonviolence. “Of course, he played linebacker, I find out, and we became wonderful friends for the rest of the pilgrimage.” Allen says that, in a few days, he will travel to Farmville, Virginia, for another reconciliation pilgrimage—this one with Representative John Lewis, the heroic civil rights activist.

Allen also tells me about the anti-lynching resolution he sponsored and helped pass in 2005, launching into a soliloquy about what he’s learned in recent years about genocide. Back when he was governor, a series of black churches in Virginia were burned down, and Allen attended a meeting with President Clinton and Vice President Gore on the matter. “I went to the Holocaust Museum, which is the best museum in this country,” he says. “And you recognize that people knew what was going on.” He thought about that experience when he decided to champion the anti-lynching apology.

Allen knows the trouble spots in his record and has ready answers. We talk about his sister’s book (“It’s the perspective of the youngest child, who is a girl”), about the noose (“It had nothing to do with anything other than the Western motif in my office”), and about the Confederate flag once hanging in his living room (“I have a flag collection”). As for his mischievous attempt to scare his classmates into believing that his school was going to be burned to the ground, Allen, who, as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates, co-sponsored a resolution calling for a crackdown on school vandalism, denies the incident had anything to do with race. “It was something like eat crap or something like that,” says Allen, who was suspended for the incident. “Your school sucks, and so forth. It wasn’t racial. Bad enough what I did—didn’t have that to it. The purpose was to get your team riled up against a rival.”

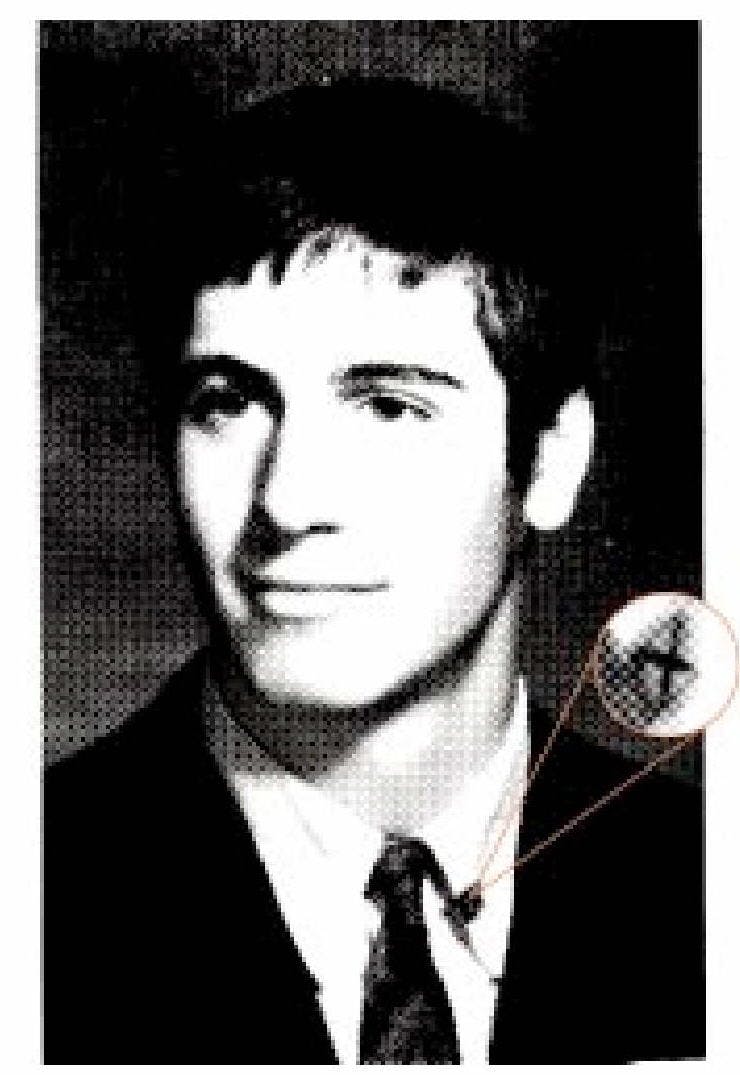

We move away from race and onto energy independence. But there was one nagging question that, even as I sat there listening to Allen go on about soy diesel fuel and lithium ion batteries, I still wasn’t sure I would ask. Two days earlier, while preparing for this interview, I had Allen’s high school yearbook open in front of me. I kept thinking about the creepy game day prank and the classmates who described the rebel flag on the car and the e-mail from Patrick Campbell: “Some of my classmates and I became rather disturbed a few years ago when we learned that George was rising in the political scene,” he had written me. “Mr. Allen is known as a racist in our Southern California society which is why we feel he relocated to an environment which was more supportive of his view points.” Maybe I had just stepped into the middle of a revenge-of-the-nerds type spat; Allen was, after all, the quarterback of the football team, and Campbell was a biology lab assistant. And did anything that happened in high school really matter today?

I stared closely at Allen’s smirk in his photo, weighing whether his old classmates were just out to destroy him. And then I noticed something on his collar. It’s hard to make out, but then it becomes obvious. Seventeen-year-old George Allen is wearing a Confederate flag pin.

Still, I wasn’t sure I’d ask him about it. And then he says something that changes my mind. As a child, Allen tells me, before he even moved to California, he learned about the painful history of the South when his dad would take the kids on long drives from Chicago to New Orleans and other Southern cities for football bowl games. There was one searing memory from those trips he shares with me. “I remember,” Allen says, “driving through—somehow, my father was on some back road in Mississippi one time—and we had Illinois license plates. And it was a time when some of the freedom riders had been killed, and somehow we’re on this road. And you see a cross burning way off in the fields. I was young at the time. I just remember the sense of urgency as we were driving through the night, a carload of people with Illinois license plates—that this is not necessarily a safe place to be.”

Now the pin seemed even worse. Why would a young man with such a sensitive understanding of Southern racial conflict and no Southern heritage wear a Confederate flag in his formal yearbook photo?

I finally ask him if he remembers the pin, explaining that another of his classmates had the same one in his photo, a guy named Deke. “No,” Allen says with a laugh. “Where is this picture?” He leans forward over his desk and tightens his lip around the plug of Copenhagen in his mouth. “Hmmm.” He pauses. He speaks slowly, apparently searching his memory. “Well, it’s no doubt I was rebellious,” he says, “a rebellious kid. I don’t know. Unless we were doing something for the fun of it. Deke was from Texas. He was a good friend. Let me think.” He stretches back in the chair, his boots sticking out from underneath his desk. “Yeah, yeah, that’s interesting. I’ll have to find it myself.” Another pause. “I don’t know. We would probably do things to upset people from time to time.”

He stammers some more, says he saw Deke in an airport recently. “I don’t know, I don’t know,” he continues. “It could be some sort of prank, or one of our rebellious—we would do different things. But I remember we liked Texas.”

The next day, at Allen’s request, I send him a copy of the yearbook photo. A few hours later, his office confirms that the pin was indeed a Confederate flag. In an e-mail sent through an aide, Allen says, “When I was in high school in California, I generally bucked authority and the rebel flag was just a way to express that attitude.” And then he’s off. He explains that he “grew up in a football family where life was integrated sooner than most of the rest of the country.” He reminds me of his parole, education, and economic achievements as governor. He also tells me about the money he’s trying to secure for minority institutions and an upcoming speaking gig at St. Paul’s College, a historically black school in Virginia. “Life is a learning experience,” he muses. In fact, he says, he’s continuing his education this very weekend at the civil rights pilgrimage. But, in the Allen versus Allen primary, every time the new Allen has the upper hand, the old Allen comes punching back. After Allen’s stirring statement, an aide adds a coda to the e-mail: The senator doesn’t remember the Confederate flag on his Mustang, “but it is possible.”