Thomas Jefferson: a film by Ken Burns (PBS)

The Long Affair: Thomas Jefferson and the French Revolution, 1785-1800, by Conor Cruise O’Brien (University of Chicago, 367 pp., $29.95)

Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy, by Annette Gordon-Reed (University Press of Virginia, 279 pp., $29.95)

American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson, by Joseph J. Ellis (Knopf, 351 pp., $26)

I.

Especially during his troubled second administration, Thomas Jefferson received a lot of hate mail. “You have sat aside and trampled on our most dearest rights bought by the blood of our ancesters [sic],” one angry correspondent snarled at the height of the embargo crisis in 1808. Another letter began, “thomas jefferson, You infernal villain,” and still another saluted the president as “You red-headed son of a bitch.” Jefferson affixed his own laconic endorsements to these messages (“abusive,” “bitter enough”) and then quietly filed them away; but he could not hide his growing annoyance. “They are almost universally the productions of the most ill-tempered & rascally part of the country, often evidently written from tavern scenes of drunkenness,” he wrote angrily to his Secretary of State, James Madison (who was also a target of poison pen letters).

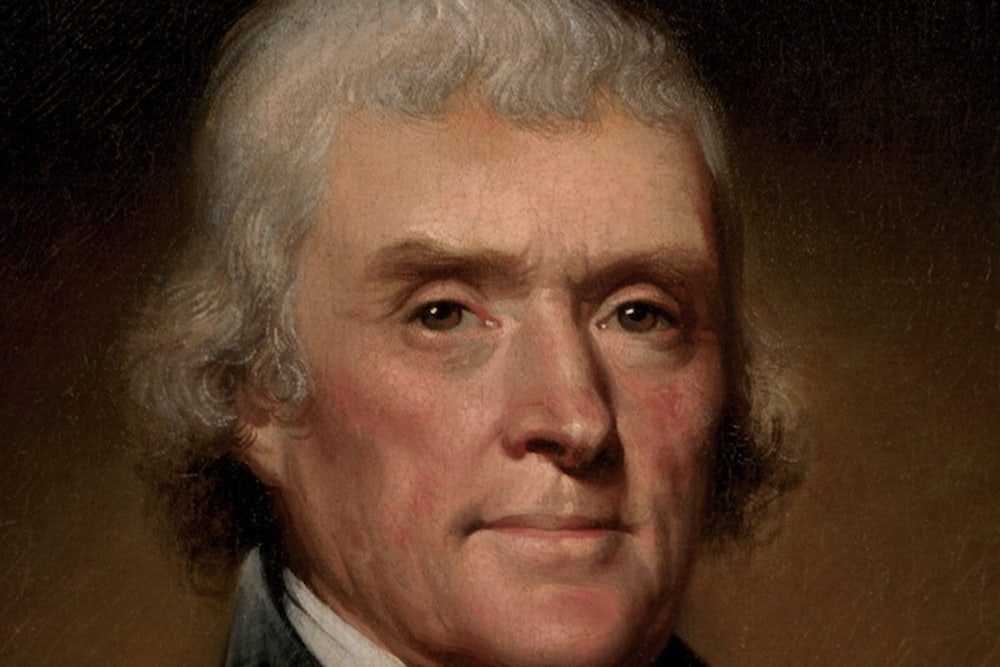

Were he alive today, Jefferson would probably regard modern American historians as a rascally bunch. To be sure, he remains a sainted figure to millions of ordinary Americans, as the author of the Declaration of Independence; and in American popular culture, to judge from Ken Burns’s commendable PBS film Thomas Jefferson, his nobility is secure. But Jefferson has been subjected to intense scholarly attack over the past thirty years, more so than any other Founding Father.

In 1963, the legal historian Leonard Levy heavily damaged Jefferson’s reputation as a civil libertarian by describing how, as president, he tolerated the suppression of opposition editors with selective prosecutions for seditious libel. Soon afterward several leading historians, including Winthrop Jordan, David Brion Davis and Edmund Morgan, challenged the authenticity of Jefferson’s anti-slavery professions and dwelled on his disparaging writings about blacks. Conservative and radical scholars have been discovering common anti-Jefferson ground on issues ranging from Indian removal to the Haitian Revolution, and they have adopted an increasingly acidulous tone. Whereas pro-Hamiltonians such as Forrest McDonald denounce Jefferson as a “wild-eyed political quack,” left-leaning historians such as Michael Zuckerman describe him as “the foremost racist of his era in America.” And now Conor Cruise O’Brien, attacking from the left and the right simultaneously, has written a book that links Jefferson’s legacy to the Ku Klux Klan, Pol Pot, Hendrik Verwoerd and the right-wing militia movement in contemporary America.

To a certain extent, all these vicissitudes of reputation are just the familiar academic boom-and-bust cycle. Undervalued by historians in the nineteenth century (when pro-Federalist New Englanders dominated the field), Jefferson enjoyed a scholarly revival in the 1920s and 1930s, when he was celebrated as a liberal champion of the Enlightenment and a patron saint of democratic reform. The dedication of the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C., in 1943, presided over by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, signaled Jefferson’s enduring stature in the public mind; and thereafter a series of scholarly monuments, above all Dumas Malone’s admiring six-volume biography, which appeared between 1948 and 1981, ratified Jefferson’s greatness inside the nation’s history departments. In recent years, inevitably, there has been a corrective, anti-Jefferson reaction. But this alone cannot explain the shrillness of Jefferson’s current critics, or why so many of them are leftists or mainstream liberals, formerly Jefferson’s defenders against the Hamiltonian plutocracy.

Somewhat paradoxically, Jefferson’s fate has paralleled that of twentieth century American liberalism. There was always something absurd about describing Jefferson, the agrarian anti-statist, as one of the forerunners of Progressive reform and New Deal reform. Jefferson’s writings on religious liberty gave the argument a certain plausibility in the 1920s, amid the Scopes trial and a revival of anti-Catholic nativism. A decade later, New Deal Democrats pointed with pride to their party’s distant genealogical connections to the Jeffersonians. Much more influential, though, was the notion, first popularized by Herbert Croly back in 1909, that modern reformers were trying to use Hamiltonian means to achieve Jeffersonian ends. (That is, it was Jefferson who inspired latter-day government efforts to rein in the malefactors of great wealth.) With that presumption, the reputations of Jefferson and modern liberalism crested at about the same time, in the 1940s and 1950s. Yet as the century has dragged on, and as American liberalism has suffered through its own intellectual and political crises, it has become harder to sustain Jefferson’s reputation as any kind of liberal forerunner.

One problem has been Jefferson’s famous defense of the French Revolution, particularly his passing defense of the Jacobin Terror. As long as 1930s-style Popular Front liberals (along with the Marxists) ennobled the Jacobins as egalitarian radicals, Jefferson looked like a fine internationalist revolutionary. But during the cold war decades, as the Jacobins (and American fellow travelers of a different kind) fitfully fell into disrepute, the delusions of Jefferson’s more enthusiastic writings on France and revolution became difficult to explain away.

The triumphs of the civil rights movement posed much graver problems for Jefferson’s reputation. In the 1930s and 1940s, the New Deal coalition of liberal northerners and the Solid South could comfortably admire a contradictory Virginia slaveholder who had also criticized slavery and proclaimed that all men were created equal. In the 1960s, as the New Deal coalition collapsed under the weight of civil rights reform, so did many liberals’ and leftists’ admiration of Jefferson. Despite his exquisite pain about slavery as “an abominable crime,” Jefferson remained a slaveholder his entire life and arranged for the manumission of fewer than ten of his hundreds of slaves, while a significant number of his fellow Virginians (including George Washington) freed their slaves.

For all of his vaunted egalitarianism, Jefferson proffered, in his Notes on the State of Virginia, some hair-raising, pseudo-scientific personal observations about the innate mental and physical inferiority of blacks, including his notion that Negroes prefer whites “as uniformly as is the preference of the Oran-ootan for the black women over those of his own species.” When he registered his philosophical objections to slavery, Jefferson always seemed more troubled by the institution’s degrading effects on whites than by its oppression of the slaves. Until his dying day, Jefferson doubted that blacks and whites could ever coexist peaceably as American citizens; and he looked forward to the eventual disappearance of blacks from these shores, preferably through emancipation, deportation and colonization.

On similar grounds, of course, almost every politically prominent white southerner of Jefferson’s time (with notable exceptions such as Jefferson’s law teacher, George Wythe, and the Virginia jurist and emancipationist St. George Tucker) could be excluded from being honored in ours. As Robert McColley, one of Jefferson’s most trenchant modern critics, has observed, Jefferson’s hypocrisy in the matter of legislative plans for emancipation was typical of the enlightened, “anti-slavery” Virginia slaveholder gentry of the revolutionary era. Yet it is Jefferson who gets singled out, and it is easy to understand why: he wrote, in the opening lines of the Declaration of Independence, the most famous summary of the American egalitarian creed. Plainly, there was less to those great words than met the eye, for they had been written by a slaveholder who believed in the racial superiority of whites.

Interestingly, many black American reformers and radicals since Jefferson’s time have been able to own the contradictions in his words and his deeds. In 1829, three years after Jefferson’s death, the free black pamphleteer David Walker angrily (and lengthily) refuted the racism contained in Notes on the State of Virginia, calling the book “as great a barrier to our emancipation as any thing that has ever been advanced against us”; but Walker also regarded Jefferson as a great man, “a much greater philosopher the world has never afforded.” Walker held up the Declaration of Independence as an unfulfilled charter for racial equality, to be secured by any means necessary. And more than a century later, Martin Luther King Jr.--speaking at the Lincoln Memorial and not the Jefferson Memorial--echoed Walker’s Jeffersonian themes (though not his violent overtones) by quoting the Declaration during the March on Washington.

Still, black Americans are unlikely to harbor illusions about an American patriot who was also a slaveholder, which may explain why figures such as Walker and King have been able to approach Jefferson’s legacy with a certain ironic detachment. “I’m a forgiving man,” the historian John Hope Franklin remarks in Ken Burns’s documentary, “therefore, I forgive him for what he did. But I remember that what he did was a transgression against mankind.” By contrast, much current historical writing on Jefferson has acquired a single-minded peevishness that at times turns into truculence. On race, as on other matters, Jefferson disappoints many modern liberals and leftists, and that disappointment has led to outrage, and so a new anti-Jefferson left has joined up with the traditional anti-Jefferson right, flinging around invectives and accusations that make “red-headed son of a bitch” sound mild.

II.

It is a little odd, at this late date, to see Conor Cruise O’Brien enter the arena in the guise of an intrepid Jefferson debunker. All of the major pieces of evidence that O’Brien marshals against Jefferson--including the egregious passages on blacks in Notes on the State of Virginia, a notorious sanguinary letter that Jefferson wrote in praise of the French Revolution in 1793, and the stories surrounding Jefferson’s alleged sexual liaison with his slave Sally Hemings--have been familiar to scholars for decades, and many of them have received special attention in recent years. Most of O’Brien’s specific charges about Jefferson’s political chicanery and opportunism were validated long ago. They are accepted by scholars who remain, withal, Jefferson’s admirers.

O’Brien seems to think that the scholarly woods are full of starry-eyed, uncritical “liberal Jeffersonians.” It is a strange idea, given the drift of historical writing over the past three decades, on much of which O’Brien himself relies. “I intend, if possible, to outrage them out of existence,” O’Brien writes of his liberal antagonists, “not out of physical existence, of course, but out of existence as the confused and confusing school of thought they actually constitute.” O’Brien is not very precise about who belongs to this “school,” apart from Dumas Malone and Jefferson’s modern editor Julian Boyd (both of whom have now been dead for more than a decade), along with Malone’s successor, the biographer Merrill Peterson, and President William Jefferson Clinton, and one or two others. But O’Brien certainly succeeds in being outrageous, and at times irresponsible, in trying to exclude Jefferson and his defenders from re-spectable company.

It adds virtually nothing to the historical record, but O’Brien’s book does make three polemical contributions to the fray. First, O’Brien charges that pro-Jefferson scholars, above all Malone, have systematically distorted Jefferson’s writings, to the point of suppressing documentary evidence. Second, O’Brien picks up two distinct and familiar lines of argument--the liberal criticism of Jefferson’s writings on race and the conservative (more exactly, Burkean) criticism of his writings on the French Revolution--and combines them, so as to portray Jefferson’s pro-Jacobinism and his racism as fatefully intertwined. Finally, O’Brien asserts that Jefferson’s image ought to be removed from the American pantheon and handed over to his true political heirs: today’s terrorist, racist right.

In pressing his case against earlier historians, O’Brien dispenses quickly with the usual courtesies and turns abusive. He attacks Merrill Peterson not simply for misconstruing one of Jefferson’s letters, but for systematically introducing his own “sentimental and otherwise misleading assumptions” about Jefferson’s character. He conjectures, rather tastelessly, that Julian Boyd tried his best to present Jefferson as a hero and then died of shock when he discovered that his idol had feet of clay. He insinuates that Boyd’s successors at the Thomas Jefferson Papers “don’t have time to read the stuff that is being edited,” which is to say that they arrive at conclusions somewhat different from his own. But O’Brien spends the most time finding fault in Dumas Malone, who supposedly filled his six volumes with “protectively emollient obiter dicta about Jefferson.”

Critics who are this aggressive had better possess an unerring command of the facts. O’Brien does not. Describing what he calls “the most drastic example I know” of pro-Jefferson scholarly tampering, O’Brien accuses Malone of glossing over Jefferson’s infamous letter of January 3, 1793, to William Short, a letter in which, according to O’Brien, Jefferson offered an “apology for genocide” in connection with the French Revolution. Malone sanitized matters, O’Brien says, by failing to quote from the letter directly, and by reducing Jefferson’s bloody sentiments to an innocuous, one-sentence paraphrase. The truth is that the third volume of Malone’s biography discusses the letter at considerable length, and quotes copiously from precisely the portions that O’Brien finds so horrifying, and offers Malone’s reasons why the letter should not be read as a blueprint for mass slaughter. In this “most drastic” instance, it is O’Brien, not Malone, who appears to have suppressed a part of the historical record. And later O’Brien, apparently without double-checking the original documents, sustains two other historians’ erroneous attribution to Malone of some borderline racist comments linked to the Hemings affair, comments that were actually written in 1873 by one John A. Jones, the editor of the Waverly [Ohio] Watchman.

But it is Jefferson, not the historians, who receives the roughest handling in The Long Affair. According to O’Brien, Jefferson’s attachment to his privileged social station and his singular contempt for blacks overrode whatever abstract criticisms he made of slavery. The Piedmont philosophe lived well enough off black slave labor. Worse, he probably kept his slave Sally Hemings, thirty years his junior, as his concubine (though even O’Brien, who believes the Hemings story and offers some speculative reasoning to back it up, admits that he cannot prove its veracity). Worse, virtually all of Jefferson’s public life and much of his private life, as O’Brien reads them, were shaped by a deep-seated defensiveness attached to his slaveholding. On this view, Jefferson’s famous battles against Hamilton’s financial and military plans arose not (as most historians contend) from his fear of an encroaching, British-style corruption of the new republic, but from his desire to shield slavery from Federalist criticism and northern-style economic development. O’Brien claims also that Jefferson’s racism and his slaveholder’s anxieties explain his abiding and “almost manic” support for the French Revolution.

Jefferson’s record on the French Revolution has long been established. As the American ambassador to France, Jefferson was caught by surprise by the revolution’s outbreak in 1789, but he immediately welcomed it as an extension of America’s revolution and a mighty blow against a rotten old regime. His early political advice to his French comrades, on the eve of the fall of the Bastille, was to persuade Louis XVI to issue a charter of rights--a fairly modest, even conservative proposal that would have left the monarchy intact (and which O’Brien fails to discuss).

Only after his return home late in 1789, as George Washington’s Secretary of State, did Jefferson’s rhetoric about the revolution become more heated, largely as a symbolic aspect of his larger domestic battles with the Anglophilic Hamilton. As those domestic battles over banks and national finance grew nastier, Jefferson became ever more enthusiastically pro-revolution, even after he received news of the September Massacres and other outrages. Finally, on January 3, 1793, writing to Short (his former personal secretary and now the American minister to The Hague), Jefferson fell into arguing that the revolution’s glorious ends justified apocalyptic means: “My own affections have been deeply wounded by some of the martyrs to this cause, but rather than it should have failed, I would have seen half the earth desolated. Were there but an Adam & an Eve left in every country, & left free, it would be better than as it now is.”

It was an appalling passage in its time, and it is all the more appalling when it is read today, after two more centuries of dictators and apologist intellectuals who have countenanced slaughtering the innocent for the sake of perfecting mankind. It was here, O’Brien contends, that Jefferson exposed his truest self, as a fanatic proponent of utopian genocide, addled by what Burke called “the wild gas of liberty.” Link up that fanaticism with Jefferson’s racism, and you have largely summarized O’Brien’s case that Jefferson foreshadowed the Klan and today’s militia.

By the end of 1793, however, Jefferson’s feelings about revolutionary France had cooled considerably, mainly because of the embarrassing efforts by the French envoy, Edmond Genet, to undermine the Washington administration’s neutrality policy--efforts that Jefferson feared would discredit him and his anti-Hamilton allies. Two years later (as O’Brien himself notes), Jefferson denounced what he called “the atrocities of Robespierre”; thereafter, the notorious XYZ affair, whereby Talleyrand and the French Directory attempted to exact tribute from three American diplomats, alienated him from the Jacobins’ successors. Looking back, in his late 70s, he repeated his original hope that Louis XVI could have been retained as a limited monarch, thereby staving off “those enormities which demoralized the nations of the world, and destroyed, and is yet to destroy, millions and millions of its inhabitants.”

And yet, O’Brien insists, Jefferson retained a lingering fondness for the revolution in Paris--as, of all things, a pretext for protecting slavery and alleviating white southern guilt. Without fear (and without evidence), O’Brien proposes that Jefferson and other Virginians used their loyalty to what he calls the “Cult of the French Revolution” as a ploy to fend off the anti-slavery jibes of Hamilton and other northern Federalists. Weary of being lectured to about slavery, Jefferson supposedly tried to turn the tables by making loyalty to the French cause the measure of one’s loyalty to human liberty, including American liberty.

III.

Every point in this argument is tendentious and is made all the more irritating by O’Brien’s tone of great discovery. In discounting Jefferson’s anti-slavery opinions, O’Brien overlooks Jefferson’s (admittedly wishful) insistence, in 1774, that “the abolition of domestic slavery is the great object of desire in those colonies where it was unhappily introduced in their infant state.” Likewise, O’Brien overlooks Jefferson’s draft in 1783 of a new constitution for Virginia that would have freed all children born to slaves after 1800 (while preparing the way for their removal), as well as Jefferson’s committee’s proposal to Congress the following year to exclude slaves from the western territories after 1800. Had Jefferson died in 1784, his modern critic David Brion Davis allows, he would be remembered as “one of the first statesmen in any part of the world to advocate concrete measures for restricting and eradicating Negro slavery.” (By contrast, Davis goes on to observe, O’Brien’s beloved Edmund Burke drafted a bill for the improvement of the conditions of West Indian slaves in 1780, preparatory to their emancipation--but Burke kept the idea secret for twelve years, out of fear of dividing the Whig Party.)

Since he argues prosecutorially, O’Brien fails to capture the tragic trajectory of Jefferson’s views. When, for example, Notes on the State of Virginia (which Jefferson did not originally intend for general circulation) was printed in a small private anonymous edition in Paris in 1785, it was, as Jefferson feared, the anti-slavery passages that caught people’s attention. (John Adams, one of O’Brien’s Burkean heroes, read the book immediately and congratulated Jefferson, claiming that his remarks on slavery were “worth Diamonds” and would “have more effect than Volumes written by mere Philosophers.”) Thereafter Jefferson would be scrupulously circumspect about his anti-slavery opinions, to the point of maintaining a virtual public silence on the subject. But Jefferson’s retreat from his more youthful convictions is a historical and biographical problem in need of an explanation, one more exacting than O’Brien’s flat description of his attachment to slavery as “a classical case of Odi et amo.”

O’Brien is on much stronger ground when he observes that, even by late-eighteenth-century standards, Jefferson never became a liberal on race, a failing for which authorities ranging from the Abbe Gregoire to various northern Federalist editors took him to task. O’Brien correctly points out Jefferson’s antipathy to the legal rights of Virginia’s free blacks, which became especially evident during the debates over revising Virginia’s legal codes in the 1770s and 1780s. And as late as the 1820s, when he acknowledged that the size of America’s slave population was too great to allow for a summary deportation of blacks, Jefferson was still cooking up colonization schemes whereby the federal government would buy all newborn slaves from their owners and eventually ship them to Santo Domingo.

It would be a travesty to portray Jefferson as a proponent of the sort of interracial American democracy that is a cardinal principle of modern liberal politics. But it is also unfair to portray Jefferson as O’Brien portrays him, as the prophet and the patron of racist evil. One can find racist statements from some of Jefferson’s southern antagonists (and even from some northerners) that are just as damning as Jefferson’s, but that also justify the institution of slavery, which Jefferson never did. The pro-slavery racism that later helped to propel southern secession had less in common with the ideas of Thomas Jefferson (whom the more thoughtful Confederates rejected as half-hearted) than with those of figures like the South Carolina Federalist William Loughton Smith, who declared in the House of Representatives in 1790 that the slaves were such an indolent, improvident people that “when emancipated, they would either starve or plunder.”

Jefferson, by contrast, struggled with his racial assumptions. In a letter to Gregoire in 1809-- a letter well-known to scholars, but not cited by O’Brien--Jefferson explained that his ideas about blacks in the Notes “were the result of personal observation on the limited sphere of my own State,” that he expressed them “with great hesitation” and earnestly wished to see their “complete refutation,” and that, in any case, superior natural talents could not justify granting anyone superior legal or civil rights. (“Because Sir Isaac Newton was superior to others in understanding,” Jefferson noted, “he was not therefore lord of the person or property of others.”)

Although Jefferson was profoundly pessimistic about social relations between whites and freed blacks, his beliefs about linking emancipation with colonization were far from extreme in his time. Indeed, when Jefferson died in 1826, most white pro-emancipationists (and even some free blacks) favored some sort of colonization scheme, unable to imagine true harmony ever existing between the races in America. In the North, especially outside New England and the Yankee cultural outcroppings of the old northwest, such views persisted into the Civil War era, even among some implacable white anti-slavery partisans. In December 1862, President Lincoln declared to Congress that “I strongly favor colonization,” by which he meant finding the freed slaves new homes “in congenial climes, and with people of their own blood and race.” Three years earlier, Lincoln had proposed “[a]ll honour to Jefferson” for declaring as a self-evident truth that all men are created equal. Would O’Brien cast Lincoln, too, as a precursor of Hendrik Verwoerd or merely as an early, muddle-headed “liberal Jeffersonian”?

O’Brien’s Burkean criticisms of Jefferson’s wild Jacobinism and its pro-slavery origins are also skewed. In fact, as O’Brien notes in passing, American popular support for the French Revolution remained remarkably strong and widespread in 1793, even after the execution of Louis XVI and the onset of the Terror. For domestic reasons, pro-French sentiment did tend to run stronger in the South than in the North--not, however, as O’Brien claims, as a contorted defense of southern slavery, which most northern Federalists were happy enough to leave alone, but chiefly due to reasonable fears (expressed in Jefferson’s numerous writings about the “Anglican monarchical aristocratical party”) that the Federalists aimed to impose a centralized state in order to prop up a northern financial aristocracy.

Indeed, some of the most forthright pro-slavery elements of the planter class supported neither Jefferson nor the Jacobins. They were political allies of the northern Federalists, and sworn enemies, as John Rutledge Jr. of South Carolina declared, of “this new-fangled French philosophy of liberty and equality.” And in later years it would be the anti-abolitionists and pro-slavery spokesmen who upheld Burkean traditionalism against the likes of William Lloyd Garrison and Harriet Beecher Stowe. It is an irony that O’Brien totally misses.

In the North, meanwhile, much of the frenzied millennial rhetoric in the everyday debates over the French Revolution made Jefferson’s passing comments in the “Adam and Eve” letter sound almost meek by comparison. (In 1794, for example, Ezra Stiles, the gentle and venerable Congregationalist president of Yale College, called with full-throated anti-monarchical enthusiasm for “more Use of the Guillotine yet” in France, so that “Right Liberty and Tranquillity can be established.”) Given the fragility of republicanism in a world of monarchs and aristocrats, it would have been remarkable had public emotions not reached such a pitch. And when their own political moment of truth came in 1800, of course, Jefferson and his supporters erected no guillotines and launched no insurrections. Instead they organized an electoral opposition that defeated the Federalists and conducted a peaceful, indeed conciliatory, transfer of power.

None of this, to be sure, extenuates or excuses Jefferson for indulging in delusions about the Jacobins, or for writing some chilling sentences to William Short, or for retreating from his early anti-slavery stances, or for endorsing crude racial theories. If O’Brien were interested only in registering those points, and in lodging a brief on behalf of certain northern Federalists regarding slavery, race and the French Revolution, there could be few objections. But that would have been banal, given all that historians have written of late. Instead, O’Brien rips portions of Jefferson’s writings out of their historical and biographical contexts and extrapolates them 200 years into the future, in order to advance his purpose, which is to turn Jefferson into the political ancestor of Timothy McVeigh.

And O’Brien is too smart to leave matters there. To complete the demonization of Jefferson, he must deny Jefferson’s authorship of the Declaration of Independence, the spiritual wellspring of American egalitarianism. O’Brien certainly gives it a try. The Continental Congress, he states correctly, entrusted the work of preparing the Declaration to a five-man committee, which also included John Adams and Benjamin Franklin. “Jefferson’s draft,” he writes, “was reviewed and corrected by the committee, before being laid before Congress, whose consensus it was designed to reflect. And Congress itself made further changes in the draft already amended by the committee.” Hence, O’Brien concludes, Jefferson was merely the “draughtsman” of the Declaration, not its author--a fact, he contends, that ought finally to “put an end to the official cult of Jefferson within the American civil religion.”

O’Brien’s account is elliptical and misleading. After taking a couple of days to draft the Declaration, Jefferson did submit his work to Adams and Franklin, but they suggested only minor revisions, on the order of substituting “self-evident” truths for Jefferson’s original “sacred and undeniable” truths. Congress then considered the committee’s draft and made several major changes, removing about one-quarter of the text. But almost all of the changes focused on the list of grievances about George III. Aside from striking two redundant words--making the rights endowed by the Creator simply “inalienable” and not “inherent and inalienable”--Congress approved the crucial opening section of the Declaration, written almost entirely by Jefferson, without comment. Thomas Jefferson, in short, was most definitely the author of the words in the Declaration that have meant the most in American history.

A flawed exercise in biographical annihilation, The Long Affair brings to mind the remark of one Jackson-era politician that it is sometimes possible to kill a man too dead. A lighter touch would have served O’Brien better. For there is one subject on which his antipathies may have unwittingly led him closer to the truth than most other historians have been willing to go. And that is the most explosive subject of all: the story of Sally Hemings.

IV.

“Why not talk about the Declaration of Independence, his battles with Hamilton and Burr …the Kentucky Resolutions?” Annette Gordon-Reed asks in her detailed and at times devastating reassessment of the Jefferson-Hemings controversy. It is a question that one hears regularly from Jefferson scholars, who have grown weary of the collective obsession with Jefferson’s sex life, and who have grown worried that, thanks to ridiculous films such as Jefferson in Paris, the obsession will eclipse an awareness of Jefferson’s contributions. Gordon-Reed is convinced that the worries are misplaced, that Jefferson’s legacy is too well-established in history and myth to be effaced by the Hemings story, and she is probably right. Still, the story, and the debate over its truth or falsity, continues to fascinate, if only because it is open to so many conflicting interpretations.

The story first gained widespread notice in 1802, when the vituperative (and racist) journalist James Callender, a disgruntled former Jefferson supporter, reported in the Federalist press that President Jefferson and his “wench Sally,” “the African venus,” had parented five children. Callender based his account on rumors that had been making the rounds in Virginia for years, and he made little effort to distinguish gossip from fact. Callender was known as a scurrilous exaggerator. But he was not an outright liar; and Sally Hemings had given birth to children whose father had obviously been white, and who, in some respects, physically resembled Jefferson.

Seventy-one years later, Sally’s son Madison Hemings--who had been born in 1805, had been freed by the terms of Jefferson’s will in 1826 and was living in Ohio--told the editor of a local newspaper that his mother had confirmed that Jefferson was the father of her children, who were born between 1789 (or perhaps 1790) and 1808. Hemings’s friend Israel Jefferson, another former slave from Monticello, also living in Ohio, corroborated Hemings’s story. (Other details in Hemings’s account jibed with the memoirs dictated a quarter of a century earlier by Isaac, another of Jefferson’s former slaves, including the claim that Sally Hemings was the illegitimate offspring of Jefferson’s father-in-law John Wayles--and, hence, the half-sister of Jefferson’s wife, who died in 1782.) In 1874, however, the prominent historian James Parton published a biography of Jefferson and merited a claim (based on information from Jefferson’s grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph) that Jefferson’s nephew Peter Carr, and not Jefferson, was Sally Hemings’s lover and the father of her children. Here, then, were two clashing genealogies, the one based on the as-told-to traditions of an obscure black family, the other based on the as-told-to traditions of one of the most famous white families in the country.

The revival of scholarly interest in Jefferson during the 1940s and 1950s led to fresh studies of the Hemings matter, the most famous of which, Fawn Brodie’s Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History (1974), argued that Jefferson and Hemings were indeed lovers, in a relationship that began in Paris in 1788 (where Hemings attended on one of Jefferson’s daughters) and lasted until Jefferson’s death in 1826. Brodie’s claim kicked off a furious debate in which, it is fair to say, the overwhelming majority of professional historians (including Malone) emphatically rejected her account, along with all other versions of a purported Jefferson-Hemings liaison. Yet the story has been given life in films, in magazines, in historical fiction and in the insistence of various African Americans living in Ohio, Illinois and elsewhere that they are direct descendants of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings.

Gordon-Reed is a scrupulous investigator who refuses to commit herself either way. It is her view that, given the surviving evidence, and short of performing some sort of DNA test using Jefferson’s remains (which may not be practicable), certainty is impossible. Still, her detailed review of the writings by Jefferson’s supposed defenders--chiefly Malone, Virginius Dabney, John C. Miller and Douglass Adair--exposes recurring patterns of special pleading, faulty logic and misreporting of evidence. Gordon-Reed allows that Fawn Brodie also made her share of blunders, including a clumsy use of gimmicky psychohistory. After Gordon-Reed finishes with the others’ accounts, however, Brodie’s doesn’t look so bad. And after finishing Gordon-Reed’s book, it is difficult to avoid thinking in terms of the probability, and not merely the possibility, of a Jefferson-Hemings liaison.

Until I read Gordon-Reed, I had taken as gospel Adair’s essay “The Jefferson Scandals,” written in 1960, but published posthumously in 1974. Adair was a brilliant intellectual historian, with a special flair for scholarly detective work. Unlike many other Jefferson experts, he believed that Madison Hemings’s account was sincere and, within the boundaries of that sincerity, accurate--an evaluation that squared with my own sense of Hemings’s recollections. But Adair found no mention in Jefferson’s farm account book of any child being born to Sally Hemings before 1795, meaning that she could not have borne a child conceived with Jefferson in Paris, as Madison Hemings claimed. Adair also tracked down the recollections of one Edmund Bacon, a Monticello overseer, originally published in 1862, which, Adair asserted, exonerated Jefferson and offered “presumptive evidence” that Peter Carr was Sally Hemings’s lover. Adair then built what seemed a plausible circumstantial case that, first, Jefferson could not possibly have been Sally Hemings’s lover, and second, that Hemings must have picked up Callender’s story, embellished it, and passed it on to her children.

But Gordon-Reed punches several holes in Adair’s theory. Jefferson did not diligently keep his farm accounts from the time of his return from Paris in 1789 until 1794, years when his duties as Secretary of State mainly kept him away from home; and it is thus entirely possible for Sally Hemings to have given birth in 1789 or 1790 and for the event to have gone unnoted. Nor would it have been surprising if Jefferson neglected to enter the birth, for entering it would have been tantamount to acknowledging his paternity, given his and Sally Hemings’s living arrangements in Paris nine months earlier. The birth of a Hemings child in 1789 or 1790 would be consistent with Callender’s claim that she had given birth to five of Jefferson’s children as of 1802. Finally, Gordon-Reed, with support from Brodie’s book, finds evidence that could explain what eventually happened to the mysterious child, who could have died, run away or been sent to live with another family.

In any event, Adair’s findings (or lack of findings) in the farm book do not settle anything. Neither, Gordon-Reed explains, do the recollections of Edmund Bacon, who only began working at Monticello in 1806 and had his own reasons to deny Jefferson’s paternity. And neither does the rest of Adair’s reconstruction of the evidence, which, as Gordon-Reed shows, is based on a fanciful handling of the facts and a highly prejudiced view of Sally Hemings, Maria Cosway (Jefferson’s famous Paris infatuation) and Jefferson himself. There is one interesting query of Adair’s that Gordon-Reed does not answer: Why would Jefferson risk his presidency and his historical reputation by continuing a liaison with Sally Hemings for at least five years after Callender’s expose appeared? But there are the vagaries of the human heart to consider, and there is also the rest of the evidence that Gordon-Reed discusses, and so that unanswered question does not settle things, either.

The most compelling evidence in support of a Jefferson-Hemings connection was actually assembled by Dumas Malone, who nonetheless stubbornly refused to believe the story. The evidence concerns proximity. We know that Jefferson and Sally Hemings were living in close enough quarters in 1789 to have conceived a child. After their return from Paris, she spent virtually all of her life at Monticello. He spent only occasional stretches of time there (except for the hiatus between his resignation as Secretary of State in 1793 and his inauguration as vice president in 1797), until he completed his second presidential term in 1809. Yet repeatedly, some months after Jefferson did visit his beloved homestead, Sally Hemings gave birth. Gordon-Reed summarizes: “The relationship was so strong that it can be described as creating a pattern. The pattern went like this: Jefferson comes home for six months and leaves. Hemings bears a child four months after he is gone. Jefferson comes home for six weeks. Hemings bears a child eight months after he is gone. Jefferson comes for two months and leaves. Hemings bears a child eight months after he has gone. This went on for fifteen years through six children. He was there when she conceived, and she never conceived when he was not there.”

It seems highly unlikely that some other purported father’s fertility would be so exactly linked, for a decade and a half, to Jefferson’s presence at Monticello. And when these facts are connected to the rest of the supporting evidence that Gordon-Reed assembles-- Madison Hemings’s and Israel Jefferson’s statements, the matter-of-fact diary notations of a Jefferson associate, John Hartwell Cocke, about Jefferson’s having had a slave mistress, the treatment of Sally Hemings’s children including their manumission, and other considerations--the case seems too strong to dismiss out of hand, as most professional historians (though not Conor Cruise O’Brien) are still wont to do.

But so what? Without additional evidence, certain fervent Jefferson admirers will never allow that he could have slept with a slave. Neither will certain fervent Jefferson haters, ranging from black nationalists to anti-Jefferson liberals, who insist that Jefferson’s racism would have precluded any sort of sexual connection with a woman of even partial African descent. And still other Jefferson haters, such as O’Brien, are bound to take the opposite tack, insisting that Jefferson’s likely relation with Hemings advances their own view of Jefferson as a moral monster. Gordon-Reed remains, strictly speaking, an agnostic, but she reasonably encourages what might be called a stance of sympathetic (though not fervent) acceptance.

In doing so, she cuts to the heart of the myths that still govern our thinking about miscegenation under slavery. Those myths lead us to imagine that an omnipotent Thomas Jefferson, the white master, must have imposed himself on the powerless Sally Hemings, the black slave girl, in scenes of more or less forcible rape. Without question, rapes did occur under slavery. Still, as Gordon-Reed smartly observes, the evidence in the case of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings does not support a story involving “thirty-eight years’ worth of nights of `Come here, gal!’” Nor, given the courtship norms of the eighteenthcentury Virginia gentry, would there have been something terribly unseemly about a 45-year-old male establishing a sexual or emotional attachment with a 15-year-old female.

Instead, we are left with a less sensational and more poignant story, along the lines that Madison Hemings outlined, the story of a match that lasted more than a decade, that began with a middle-aged, widowed white statesman (who had pledged to his dying wife that he would never remarry) and a young, fair-skinned African American woman. The woman was almost certainly the half-sister of the widower’s late wife--and she was also the widower’s slave. But enslaved though she was, the woman, by assenting to the match, gained enough influence over the widower to extract the promise that he would free her children, and years later she held him to his promise. Bound though he was by the rules of his class to keep the relationship secret, the widower, a vigorous man who had never abjured female companionship, sustained some semblance of connubial affection, at least when he was back on his Virginia mountainside. The hard facts of slavery, compounded by the widower’s earlier pronouncements against miscegenation and by his need to sustain his respectable position in politics and society, rendered the relationship absurd, almost to the point of tragedy. But neither the widower nor the young woman could undo those facts, and so they lived with them as best they could.

The prospect that Madison Hemings’s story came close to the truth should not, however, fill us with horror. It should fill us with cheer. Miscegenation is not always the same thing as subjugation. If one of the white mandarin men who founded this country respected, even loved, a black woman slave, and created a real but underground family with her, then it is only further proof that intimacy between black and white, and the possibility of decency between black and white, existed even in conditions of brutal racial oppression, and so may exist in the bettered but still troubled conditions in which we now live.

V.

“Almost every other American statesman might be described in a parenthesis,” Henry Adams wrote in his great history of the Jefferson and Madison administrations. “A few broad strokes of the brush would paint the portraits of all the early Presidents with this exception …but Jefferson could be painted only touch by touch, with a fine pencil, and the perfection of the likeness depended upon the shifting and uncertain flicker of its semi-transcendent shadows.” Adams dismissed James Callender’s reports about Jefferson and “Black Sally” as libelous and based “on a confusion of persons which could not be cleared up.” (He also thought that the story was utterly irreconcilable with Jefferson’s “refined” and “feminine” nature.) Yet even if it turns out that Callender’s account was not wholly false, Adams’s general point about Jefferson’s elusiveness holds true, in the Sally Hemings matter as in practically everything else. Move the light even slightly, and the Jefferson whom you thought you knew and understood looks different. Try and describe him whole, and you wind up with a string of paradoxes, with Jefferson the patrician democrat, or the egalitarian slaveholder, or the rustic cosmopolitan, or the pragmatic ideologue.

The strength of Ken Burns’s Thomas Jefferson is its attention to the nuances in Jefferson’s character and career. The film is not flawless. It contains some factual errors, as when it confuses Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, a national contender in 1800, with his brother Thomas. More surprisingly, there are annoying visual mistakes: Delacroix’s famous allegory of 1830, “Liberty Leading the People,” for example, is used to illustrate the events of 1789. Lacking the photographic details that have enriched his previous documentaries, Burns has a difficult time bringing the eighteenth century to life. It is weird to include “Simple Gifts,” the Shaker hymn, on a Jefferson soundtrack. And as in their series on the Civil War, Burns and his scriptwriter Geoffrey C. Ward have a weakness for sentimental passages that detract from a fuller understanding of political events, especially during Jefferson’s presidency.

Still, Burns’s effort is historically on the mark about most of the important themes, including Jefferson and slavery. Where the facts are in doubt, as in the Sally Hemings matter, the film presents all possibilities and wisely suspends final judgment. Where the facts are agreed upon but historians still differ, the film clearly and calmly airs these differences. Above all, Thomas Jefferson tries admirably hard to convey the complexity of Jefferson’s personality, including his stubborn faith in a benign providence despite some crushing personal losses.

These virtues are even more in evidence in American Sphinx, a new study of Jefferson by Joseph J. Ellis, who appears as one of Burns’s talking heads. Ellis is not exactly easy on Jefferson. On some points, such as the “Adam and Eve” letter--which Ellis describes as “an extreme version of what might be called revolutionary realism ... in the Lenin or Mao mold”--he is nearly as severe as O’Brien. Yet Ellis knows that Jefferson’s essential ideas cannot easily be construed from the sentiments contained in a single private letter, or even several letters; and his legacy cannot be converted into the political positions of our own drastically different political and intellectual world. There were, without question, some striking consistencies in Jefferson’s thinking over the course of his long political career; and there was much else in his thinking that he himself, at least, believed to be consistent. But to judge him solely on the basis of the causes and the doctrines that he espoused--or, conversely, to judge him on the basis of his failures to live up to those causes and those doctrines--is to traduce Jefferson, to simplify him, to misunderstand his place in our early history. If he was not quite the enigma that Ellis makes him out to be, he was certainly a paradox.

Jefferson deserves his reputation as an Enlightenment polymath, but he was hardly the most imposing American political thinker of the revolutionary generation. His ally Madison was wiser and more original; his foe Hamilton was bolder and more brilliant; and his on-again, off-again friend Adams, though ponderous, was more prolific. Shy and studious in manner, with a thin high-pitched voice, Jefferson was also an unimpressive public speaker. But none surpassed him in his abiding devotion to the Whig republican principles that originally inspired the patriot leadership of 1776--above all, an intense distrust of concentrated political power and public debt as tools of government corruption. None surpassed him (except perhaps Thomas Paine) in his utopian conviction that an age of reason had truly dawned, in which an enlightened humanity had gained the power to abolish the ancient scourges of kingship, war and oppression. And none matched what John Adams described as Jefferson’s “happy talent in composition,” his ability to proclaim the revolutionary leadership’s ideas in precise and radiant prose.

His optimism about the power of individual human reason at times reached visionary heights, with mixed results. When the spirit was upon him, Jefferson produced all sorts of private schemes for human betterment, including dividing the nation up into small, self-governing ward republics. Occasionally (and mainly in his private correspondence), he stretched his ideas and his loyalties to their logical conclusions, as in his awful vaporizing about Adam and Eve. During the last two years of his second presidential term, moreover, his Enlightenment idealism led him to stick by his experimental embargo policy (designed to avoid armed conflict with France and England) long after the policy had battered the nation’s economy and had nearly ruined his political reputation.

In his more adroit moments as a political leader, however, Jefferson perceived the limits of his idealism and adjusted his words and deeds accordingly, as experience (and from time to time, self-preservation) demanded. Having originally spurned political parties as destroyers of republican harmony, he wound up directing the first semblance of a national electoral organization, in order to remove from power what he considered a corrupt Federalist faction. Having railed against inflated executive power and federal spending, he went ahead with the Louisiana Purchase, in order to expand and to secure what he called America’s “empire of liberty.” Having celebrated rural virtue in Notes on the State of Virginia, and bid Americans to rely on the Old World for manufactured goods, he later allowed that “we must now place the manufacturer by the side of the agriculturalist.”

Less happily, as Ellis calmly but unflinchingly explains, Jefferson also adjusted his idealism about slavery after the mid-1780s. As soon as his Notes began circulating among his fellow southern planters, Jefferson, alarmed at a possible loss of political favor and leverage, backed off from what had been his leading anti-slavery role. Other factors also made him skittish on the subject. He found it difficult to square his pessimism about race relations with an easily practicable plan for dealing with freed slaves. His mounting debts to various English and Scottish creditors deepened his awareness of how thoroughly his own financial well-being relied on the value and the labor of his slaves. And if Madison Hemings’s story is true (which Ellis doubts), Jefferson had additional personal reasons, after the mid-1780s, to say as little about slavery as possible.

Instead, Jefferson withdrew into what Ellis aptly calls a position of “self-serving paralysis.” He hated slavery and beckoned to its eventual eradication, but he would no longer publicly endorse any plan of emancipation. He looked to younger men and to future generations to take up the battle--too weary himself to advance a cause whose time had not yet come. Ellis quotes the Duc de La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, the liberal French aristocrat who, after escaping the Terror, paid a visit to Monticello in 1796: “The generous and enlightened Mr. Jefferson cannot but demonstrate a desire to see these negroes emancipated. But he sees so many difficulties in their emancipation even postponed, he adds so many conditions to render it practicable, that it is thus reduced to the impossible.”

Finally Jefferson fancied himself as a tragic figure who could do little more than keep careful and benevolent watch over the slaves--members of “my family,” he called them--whom fate had entrusted to his care. We are left with an image of Jefferson as increasingly self-deluded on slavery, shielded from any pangs of hypocrisy by his fatalism and his powerful reserves of denial. In the 1820s, Jefferson’s determination to evade the slavery issue led him so far away from his youthful reformism that he backed the pro-slavery side in the Missouri statehood debates, on the specious grounds that if slavery was allowed to expand further westward, it would become diffused and weakened.

But more telling than any of Jefferson’s political positions was the way in which he arranged life at Monticello, as the enlightened patriarch presiding over his Palladian retreat, amid his books, his family, his gadgets and his guests--but with almost all of his slaves (save for the privileged, fair-skinned Hemings clan) living and working out of sight, further down the mountainside or on one of Jefferson’s remote estates. “[T]here were no Negro and other outhouses around the mansion, as you generally see on [other] plantations,” the overseer Edmund Bacon recalled. That is, Jefferson at Monticello did as much as he could, physically and psychically, to distance himself from the fact that he owned other human beings. In his rural seat of Reason, unreasonable slavery, and the blackness that was its emblem, could not be expelled, and so Jefferson concealed them as best he could.

VI.

The Civil War, followed a century later by the Second Reconstruction, exploded Jefferson’s legacy on slavery and race. The era of high industrialism, mass immigration and urban growth at the turn of the last century destroyed what remained of his vision of a homogeneous agrarian America. The New Deal, and then the cold war, enlarged the lineaments of national political and military power beyond anything Jefferson would have thought possible or desirable. The mechanistic natural laws on which he based his views of man and society no longer stand. “The entire mental universe in which Jefferson did his thinking has changed so dramatically....” Ellis writes, “that any direct connection between then and now must be regarded as a highly problematic enterprise.”

What survives of Jefferson’s philosophy exists largely in strange combinations, right and left. The conservative wing of the Republican Party, as Ellis observes, upholds a nostalgic version of the Jeffersonian idea that the government that governs best governs least--except, perhaps, when it comes to government involvement in the moral life of the citizenry. Modern liberals and Democrats are all for the promotion of equality, but with ideas about positive state action and group rights that Jefferson would have found anathema. Perhaps it would be well for these partial Jeffersonianisms to cease and to desist. Perhaps Jefferson cannot provide political guidance, apart from his famous injunction to Madison that “the earth belongs in usufruct to the living,” and that we must truly be the masters of our own fates.

But Ellis is not prepared to give up on Jefferson’s pertinence. He astutely locates a powerful Jeffersonian legacy in the ways Americans of diverse opinions continue to frame their views about personal freedom: “Alone among the influential political thinkers of the revolutionary generation, Jefferson began with the assumption of individual sovereignty, then attempted to develop prescriptions for government that at best protected individual rights and at worst minimized the impact of government or the powers of the state on individual lives.” Illusory though that image of sovereignty might be, it has long endured as a legitimizing principle and core conviction of American politics, liberal and conservative, forever putting more forceful claims of communitarian regulation or group entitlements on the defensive. On the right, it has become a bromide for the unfettered pursuit of self-interest. On the left, it has appeared as what Lincoln, in 1859, called Jefferson’s “superior devotion to the personal rights of men, holding the rights of property to be secondary only, and greatly inferior.” We are not, in any way, a consensual people; but most of the time, our conflicts revolve around how best to secure the individual sovereignty that Jefferson proclaimed.

And there is more to Jefferson’s legacy. Ellis calls it a style of political leadership “based on the capacity to rest comfortably with contradictions.” No, Ellis does not mean that Jefferson knew glibly how to believe in everything. Jeffersonism is not Clintonism. (The present occupant of the White House certainly does not concur with his Enlightenment predecessor that there are fixed rules of nature.) Ellis is referring, rather, to Jefferson’s ability to lead a nation of sovereign individuals who are preternaturally suspicious of government. And in this sense, the protean quality of Thomas Jefferson is indeed serving Bill Clinton in good stead. Jefferson’s elusiveness, his outright deviousness, was a great political strength. As Ellis shows, it allowed different constituencies to see in him what they wanted to see, and this allowed him to lead while appearing to be a follower.

But there was something even greater about Jefferson, and Ellis does not quite pin it down. More than any of his American contemporaries, Jefferson took some of the most radical ideas of the Enlightenment and put them to the test in the highest reaches of the real political world. His failures, his compromises, his flip-flops and his personal shortcomings will forever be seized upon by his critics--and rightly, for they exemplify the limits of rationality in politics. And yet America has been far richer for Jefferson’s hypocrisy, for the egalitarian and democratic impulses that he infused into our public life. Ten days before he died, Jefferson wrote that “the general spread of the light of science” had “laid open to every view the palpable truth, that the mass of mankind has not been born with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few, booted and spurred, ready to ride them legitimately by the grace of God.” Before Jefferson and his revolutionary generation, those saddles and those spurs were fully legitimate. They are legitimate no more, even if they have not all been fully destroyed. We are still far from fulfilling the Declaration’s creed about equality before the law. Nor have we provided, as the Declaration demanded that we do, the equality of opportunity to gain a modest prosperity: if wealth is the measure of opportunity in America, we have become more unequal in recent times. And yet, over the centuries, more and more Americans have also ridden the ride of which Jefferson dreamed, not only by the grace of God, but also by the grace of Jefferson.