JANUARY 2, 1996.—It is difficult to believe that the race for the Republican nomination, or any other race for that matter, could begin in Manchester, New Hampshire. On the way up, in the whirling snow, cars zipped past me on the highway as if immune to danger; every twenty minutes or so one of them would spin out of control and go plunging off the side of the road. The same people who refuse to fly after a bomb explodes on a commercial airliner hurtle along grimly through a blizzard toward almost certain disaster. Live Free or Die. When I arrive, the only sign of life at 8:00 in the evening were several cars and a couple of dark stooped figures on foot, all heading through the snow in the same direction. I followed on the assumption that if there was only one place in Manchester to go to get out of this mess I wanted to be there. Their tracks ended at the front door of a porn video store called Forbidden Fruit. Then in the distance I spotted a light. On closer inspection it is Phil Gramm's campaign headquarters. A young man is tucked behind a desk at the back. I knock and do my best to explain my business, even though I am not exactly sure what that is. Happily, he seems almost to be expecting me. He keeps calling me “sir,” and instead of just handing me Gramm's schedule, he sits down and laboriously copies out by hand what he feels I need to know.

Tomorrow Gramm is coming to New Hampshire.

JANUARY 3.—The phone rings at 7:00 the next morning. It's another eager Gramm aide wanting to know if I would like to attend a breakfast at 8:00 at which Gramm is speaking. “I can come pick you up,” he said, with a hopefulness that gave him away. I may be new to the campaign trail, but I'm not that new. I rolled over and went back to sleep. Outside, the snow fell.

Two hours later it turns out that all one needs to do to become a campaign reporter is call the campaign headquarters, find out where the candidate is going and tell them you want to come along. They don't seem to care very much where you are from, just as long as you agree to play the role of journalist. If you insist, they will fetch you at your hotel and drive you halfway across the country. For free!

This evening's event was an hour passed with a family of undecided voters in a town called Salem. They are a couple in their late 30s named Matt and Kate Conway. He sells hockey equipment, she is a “housewife or homemaker or whatever the correct term is,” as he put it. Before Gramm arrives, Matt tells the assembled journalists that “we are a typical middle-American Ozzie and Harriet family; we really are.” The point of the meeting is for Gramm to display his commitment to a balanced budget.

Gramm arrives, and within five minutes the Conways seem like guests in their own home. Gramm sits down between them at their dining-room table and starts to make magic with his numbers. He does not explain how he would balance the budget or even why the budget should be balanced—except for a felonious chart he uses to show how much money the typical American family would save from the resulting decline in interest rates. But he does persuade the Conways that Phil Gramm, unlike any other politician, truly is committed to balancing the budget and giving America back to the people. He peddles his balanced budget idea like an Amway salesman; from the moment he pulled out his foot-high laminated chart I kept waiting for him to offer them a new line of steak knives or household disinfectants, but no, he just kept rambling on and on about the budget. Even when the typical 8-year-old twins who belonged to this typical American family rushed into the dining room and demanded to play with mommy and daddy Gramm said, wittily, “Let's see how good they'll feel when they find out they'll have to pay $197,000 in income taxes just to cover the interest on the public debt.” I thought I saw one of the children flinch, but perhaps I was mistaken.

Gramm is charming enough, but he's no match for Clinton. His trouble is that he isn't terribly interested in what other people have to say. I recall reading somewhere about Gramm's upbringing in Columbus, Georgia. After his father became ill his mother used to take little Phil from their lower-middle-class house to the rich folks' neighborhood, where she would point to the houses and say, “If you work hard you can live in one of those!” People really do think like that. The effect on Phil seems mainly to have concentrated his mind on winning the biggest thing he could possibly win: that's what motivates him, as it motivates Dole. He's not interested in the people who vote for him. In Fran Lebowitz's formulation, for Gramm the opposite of talking isn't listening. It's waiting. When the Conways said something he held his breath until they finished—offering an encouraging nod and his endless taut ironical mouth—and then launched into some speech. (“ Well, let me tell you the point I want to make....”) The best he could do was relate whatever they said to his own life:

Matt: “I was born in Pearl Harbor.”

Phil: “Oh, really? My wife is from Hawaii.”

The mouth is the giveaway. Hard, tiny dimples frame his pucker like parentheses. At some point in his life he learned that the way to look smart was to look as if you were always about to laugh at whatever anyone, himself not excluded, was about to say. Every now and then Gramm gets wrongfooted and greets the news of some terrible human tragedy with his little mouth-dimples. Then he has quickly to change his expression, to show that he is still listening. The trouble is he doesn't really have another expression. He wants to put everything that is said inside his parentheses. Talking to Phil Gramm is like being in on one endless aside.

Then again maybe I've got it wrong. Gramm's teeth are very bad; he has the worst orthodontia in this campaign, by far. They are discolored and look as if each and every one has been sharpened to a point—more like animal teeth or pumpkin teeth than human teeth. They alone give you some idea of the poverty he experienced as a child. On the rare occasions he smiles he is frightening. Perhaps he clenches his mouth the way he does because he wants to convey bonhomie yet is uncomfortable with his smile. If so, it shows how physical traits can lead to emotional ones. He's worn his wry look so long that he has become permanently wry.

Whatever the cause of the Gramm mouth, the effect is to make people feel that they are in on some joke they probably don't quite get. Except he's chosen the wrong people to do this with. Kate Conway is fairly nervous, as anyone would be who is suddenly facing a dozen people she does not know asking her questions about the future of the republic. But Matt is Mr. “Capital Gang.” Twenty minutes into the visit he was offering Gramm some fairly plausible-sounding advice about how to package his views. He mentions in passing that he lives near “Bush's FEMA head,” whatever that is. He said—I swear—that they “came very close to buying the house next to John Sununu's.” And he has this strange habit of discussing himself as an archetype. In the context of what was supposed to be a perfectly ordinary conversation (albeit with half a dozen members of the press corps looking on), he'd say things to Gramm like “this house was about $200,000 to get our piece of the American dream.” Do real people really think like this?

PERHAPS THIS IS the place for a brief note on the weirdness of New Hampshire. It contains the world's most professional electorate. Every candidate knows that 10,000 New Hampshire votes might be the difference between winning the White House and ending one's days in obscurity; every voter knows this, too. The state has organized itself so that it is not organized: no one can deliver many votes. Every single citizen must be thoroughly sucked up to, one at a time. The primary is therefore a painful extortion: the people may say that they are for less taxes and smaller government, but they are engaged in the shakedown and are only just worth what they are paid for their votes. And it works. New Hampshire currently is one of the biggest per-capita recipients of discretionary Medicaid dollars. The Portsmouth Naval Yard has managed to remain open during the furlough. Half of New Hampshire seems to have pictures of itself shaking hands with the president on its living room walls; the other half actually gets political appointments after the election. (Apparently Clinton made some N.H. nobody the ambassador to Belize.)

The state is famous for surprising election results, and no wonder. Everyone involved has an interest in making this campaign interesting—thus attracting reporters, attention, campaign promises and money to themselves. Every New Hampshire reporter—indeed every New Hampshire resident—is like a sports announcer trying to keep his audience glued to the box during a rout. The other day one of the campaigns, for example, gets a call from a fellow named Carl Cameron, the only local New Hampshire television reporter (ABC affiliate) and thus a person of influence. He tells the campaign the piece he wants to do that night. He'll lead with the fact that Dole seems to be running away with it, but New Hampshire has a habit of upsetting front-runners. Then he'll assert that Dole's support is not terribly enthusiastic—cut to man on street who says he isn't very enthusiastic about Dole—and feed the competing campaign a question about Dole, which it can put away. So there! You see! Dole's in trouble.

At the end of the home visit I overhear Matt ask Gramm about fuel subsidies, and Gramm said he was doing what he could for the state. This in spite of the fact that the entire evening was devoted to the importance of getting the government out of the Conways' hair. Matt and Phil chitchat privately about pork. Although Gramm doesn't listen he is acutely observant. One of the key features of the house, which I couldn't believe he would bother to notice, was the dining-room furniture. Unlike everything else in the house—and the house itself—it looked old and cherished. At the end of his disquisition on fuel oil Gramm asks, “Did you get this furniture from your parents?” After Gramm leaves the Conways tell the journalists that though they are genuinely undecided they liked Gramm immensely and may well vote for him.

One other odd trait of Gramm's: he's a foot masturbator. The moment he climbs aboard a plane or into a car he removes his shoes and massages his feet. His feet don't smell, but it is still a revolting habit, like chewing tobacco.

JANUARY 7.—It is a special day—the day of the Republican State Committee Dinner, which will gather all the candidates in one room at the Holiday Inn. By 8 a.m. the Morry Taylor people have planted their signs in all the best places. Four teenage supporters of Buchanan are left to wave their signs on a frozen street corner. It is thirteen below zero with the wind-chill factor, and yet they seem perfectly happy to stand there and jab their little signs up in the air in an attempt to catch the attention of passing motorists. Driving past them with the chauffeur from the Holiday Inn, I asked him who he was for. “I don't pay much attention to voting,” he said. Then a little while later he said, “Clinton seems to be doing about as good a job as you can do. I guess I'd like him to stay there.” I think I made him feel badly about not having an opinion. This is an example of a second, related New Hampshire phenomenon: people who have no natural interest in politics feel guilty about it. They acquire political opinions to avoid social embarrassment.

By 4:30 a crowd awaits the candidates. Along the corridor leading to the grand ballroom campaign aides open booths and distribute literature. There is also one nonpartisan booth called GOP Shoppe. It sells paraphernalia: buttons, ties, sweatshirts, etc. The owner, a young Republican, tells me that while business has been booming in Forbes and Buchanan he did not sell a single Dole item—nary a button—in the last three weeks of the year. Although he is their front-runner, Republicans remain much less interested in plastering Dole's name all over themselves than just about any other candidate.

Disappointing news: Dole, Gramm and Forbes are not going to make it. They are snowed in in Washington and New York.

Republicans stand around ostensibly enjoying a cocktail hour but in fact mourning the absence of the front-runner and waiting for the dinner to begin. Jim Courtovich, Gramm's campaign manager, comes over and spins me till I'm dizzy: “You've heard of the A Team,” he says. “Well, what we've got here is the B Team.” But here even the B Team are celebrities. People are actually asking Morry Taylor for his autograph. Morry Taylor! A crowd gathers in a bar to one side of the hotel, and you would think from its size and enthusiasm that Michael Jackson is about to turn up. “We're waiting for Dick Lugar to arrive,” one of the enthusiasts explains.

At length I spot the Conways, the self-described typical middle-American couple, standing alone in the middle of the vast ballroom. Matt explains they are sitting at a Forbes table. It turns out that his other next-door neighbor (the one who doesn't work for Gramm) works for Forbes. He realizes how fickle he appears, what with him having sung the praises of Gramm in his foyer to the national press just three days earlier. “The Gramm people called and asked if I wanted to sit next to the senator,” he says, “and I would have liked to... I really would have.”

Matt has a confession to make. His home visit from Gramm wasn't as spontaneous as it appeared. The Gramm people called to prep him before the senator arrived. Alarmed by how well and broadly informed he was they asked him to stick to the budget. “They especially didn't want me to ask anything about Bosnia,” Matt now admits. I ask Kate if she noticed that Gramm looked her in the chest as he spoke to her. She did; it was one of the things she noticed most about him. Her husband seemed slightly shocked. “I didn't want to tell you,” she explains.

At the dinner I am seated not with the press but with the Buchanan supporters, who occupy a large corner of the ballroom. Unlike the Forbes supporters, who clearly are wearing what they do every night, the Buchanan supporters look as if they have dressed up for the first time in years. The more you look at it, the more the Buchanan section reminds you of the cast of some morality play waiting to take the stage. In addition to the jowly red- faced old men and the paunchy, bench-pressing young men, the section contains a real live minister in collar and a young woman who is a dead ringer for Brooke Shields. The young woman has no interest whatsoever in the priest, the politician or the speeches; indeed, she works at cross-purposes with them. She is busy winning the competition with them for the attention of the New Hampshire Republican mind.

Nothing much happens the first half of the dinner, but then Alan Keyes carves a path through the Buchanan section. Keyes has been sounding a single note: he is the moralist in this campaign. It's an astonishing position for someone who is running against Pat Buchanan, and it says a lot about the Republican race thus far that he fits in as well as he does. Keyes has no interest in economic issues, only social ones. He wants the government to make people behave themselves, more or less. This seems to mean principally not having sex with anyone who is not your spouse.

To promote his program, Keyes works every table in our corner of the room. He shakes the hand of every Buchanan supporter. He tries to get off cheaply, as they all do, by shaking my hand and telling me how good it is to meet me. I explain to him that I write for The New Republic and that, if he buys a subscription, I will write an article about him. I want to see if the raging moralist can also operate on the level of irony. He can't. He turns and says, quite seriously, “You are easily bribed.” True enough, I think, but I don't stay bribed for long. Before I can finish the exchange, however, all hell breaks loose. Buchanan's press director, Mike Biundo, jokingly asks Keyes what it would take for him to endorse Pat. Keyes flips out, yelling and screaming about what a racist Pat Buchanan is.

It turns out that a week or so before, Buchanan included in one of his speeches a story about John Dean, John Mitchell and the Hopi Indians. (The gist of it was that Dean plea-bargained to continue his charitable work with the Hopi Indians. Mitchell's lawyer followed. But before he did, Mitchell leaned over to him and whispered in a voice loud enough that the whole courtroom heard, “If they offer you the Indians, turn them down.”)

“Why is this funny?” screams Keyes at Biundo, so loudly that all of a sudden our table is the focus of attention for half the ballroom. “Will someone please explain to me why this is funny?”

Certainly, the way he tells the story, it isn't funny at all, but who knows? With a little less indignation and a little more work on the punch line, it might get a chuckle. You can't help but pity poor Biundo. He is sitting there with a kind of nervous nausea on his face, staring up at a black man raving on like a lunatic about the importance of Indians to the Republican Party. If you saw this scene unfold on the street you would cross over to avoid the man who is shouting and wonder why they ever let those people out of the mental institutions in the first place. But here it is a major media event. Reporters with notepads and bearded guys with TV cameras come racing over to capture the moment. The New Hampshire primary was passing before Mike Biundo's eyes. You could see him thinking: I'm going to be remembered as the guy who hates Indians.

If Keyes is faking it, he's doing a great job. He's ranting on about how he just met with Native Americans who wept at the thought that abortion was legal and yet he couldn't get them to join the Republican Party because Pat Buchanan was running around America making fun of the natives. “Do you find that funny?” he shouts again. Now virtually every camera in the place is lined up so that Keyes can repeat his rage to CNN, WMUR, the Boston stations, etc. And he does! He gets angry all over again. The most conservative candidate at a conservative convention is openly gunning for the p.c. vote. It's probably not the first time that a black man has charged Pat with racism, but it may be the first time that a black man has charged Pat with racism against Native Americans.

I spy Buchanan looking oblivious across the ballroom and beat a path to him.

“What have you got against Native Americans?” I ask.

He has not the faintest idea what I am talking about. I relate as best I can what Alan Keyes is telling the world's media on the other side of the room. He dimly remembers, then he fully remembers, his speech. “Oh, Christ,” he says, “That wasn't a joke. It happened. Mitchell actually said that!”

“What exactly did you say?” I ask him suspiciously.

He starts to try to explain himself but then wisely thinks better of it. Anything he says will sound absurd. He says, “There's no point in going over this,” then turns away.

The only surprises during the speeches were Alexander (soporific) and Keyes (electric). Everyone had a crack at Dole, and the Dole supporters cheered most loudly for the other candidates. Buchanan was typically popular, bringing down the house with a joke about how Steve Forbes couldn't make it tonight because his polo ponies had caught the flu. Richard Lugar was auto-enthusiastic; he shouted and waved and did all those things a genuinely passionate speaker might do, except be genuinely passionate; he looked like a wind-up toy into which someone had inserted batteries one size too large.

JANUARY 8.—There are two things I've never read anywhere about Pat Buchanan but that become apparent the moment you start hanging around with him on the campaign trail. The first is that he has difficulty with children. He has no ability at all to enter into their world. At a breakfast with activists this morning an adorable 6-year-old girl is put forward by her mother to ask a question. “What will you do to take all that bad stuff off TV?” she asks.

Buchanan puts his hand apart like he's just caught a basketball and is looking to pass it on, the way he does when he's delivering an impassioned speech, and says, “Maybe we can use the bully pulpit of the presidency to clear that TV up.” Then he launches into a powerful diatribe. The little girl shrinks behind her mother's skirt, as well she might.

Balancing against this is Buchanan's other surprising trait: his gift for telling people what they want to hear; or, rather, for not telling them what they don't want to hear. Buchanan is famous, of course, for saying exactly what he thinks no matter whom it offends. But there are all sorts of subjects that he doesn't care to take a stand on. One small example: a man slides into a booth beside him at a diner and announces he is a supporter and asks Buchanan what he thinks of Christie Todd Whitman. Buchanan flinches slightly, as if his mouth caught whatever he was going to say instinctively on the way out and stored it somewhere in his cheek, and asks, “Tell me, what do you think of her?”

“I love her!” the man enthuses.

Buchanan just nods along as the man sings her praises and then changes the subject. He never says what he thinks. He does this sort of thing a dozen times in a single campaign day.

Buchanan alone has ventured up into northern New Hampshire; with the exception of Alexander, who is doing some light lifting in the southern part of the state, the other candidates are either trapped by the blizzard down South or drinking hot chocolate in their hotel rooms. Today, New Hampshire is transformed into Lunaticville, USA. Hundreds of miles of blue highways have been lined with Buchanan signs planted by his advance team. I travel behind a van carrying Buchanan, listening to Buchanan blast the world as we know it to bits on talk radio. We stop in small town halls and libraries and are met by groups of twenty and thirty people known by the Buchanan campaign as “activists.” (By definition, anyone who bothers to walk through a foot of snow to get to Pat.) Men who haven't shaved or bathed squeeze in beside Buchanan in roadside diners to tell him how pissed off they are. Traveling with Buchanan is a tour of American anger. One of his supporters, a middle-aged man with a dry fly sticking out of a Boston Red Sox baseball cap on his head, even says, “I'm so angry that I got to go to anger classes.” Pat thinks this is a joke of some sort, but it's not: some local judge has sentenced the guy to anger therapy. As the man slides out of the booth to make room for another pissed off person he tells me that in the past five years he has had emphysema, cancer, triple-bypass surgery and “the knocks,” whatever those are. His best friend put a bullet through his head last year. “Mr. Buchanan is a good man,” he says.

Buchanan sits in the center of his campaign as calm as the eye of a hurricane. His speech is always the same: he starts out by teasing a small child in the front row until she looks like she wants to cry and then turns his attention to the giggling adults. He attacks NAFTA, Japan, federal judges, Pat Schroeder's $4.2 million government pension and companies that shut down factories and move jobs overseas. He supports the Founding Fathers, term limits for everyone, including judges, and campaign finance reform. He is extremely articulate and, I imagine, persuasive. If you had to distill his message into a sentence it would be this: vote for me and the world will return to the way it was before honest American workers lost control of their country. He's a nostalgia salesman. Like all nostalgia salesmen he appeals to everyone who knows nothing about the past and is unhappy for whatever reason with the present.

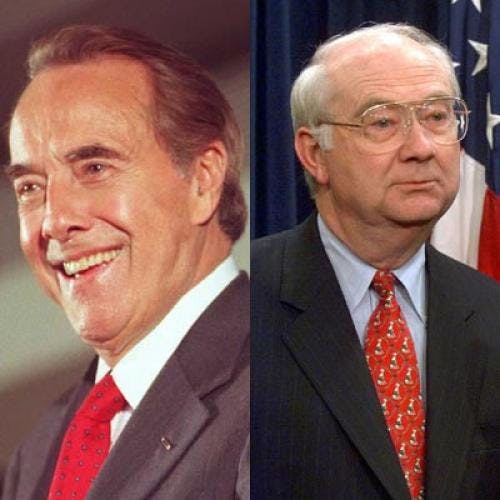

At lunch with Pat Buchanan the conversation drifted onto the subject of Bob Dole's health. I said I didn't think he looked so good. This is every Republican candidate's fantasy: every one of them has a scenario wherein Dole drops out and he wins. Pat doesn't yet need this for consolation. He thinks he can beat Dole. The campaign aides leave it alone until finally the one they call Hollywood says, “Well he is, what, 73?” That's the signal to start tossing the dirt on the coffin.

“Yeah, 73,” says another of the aides. No 72-year-old in American history has been accused so often of being 73 as Dole has been over the past few months.

“An injury like that will take a lot out of you,” says the aide they call Hollywood because he has been filmed both by MTV and ABC over the past week. “He had that operation on his prostate, too,” says Pat, thoughtfully.

People who attack Buchanan as an ugly man with ugly views miss the whole point of him. He is enormously likable, and I'm sure that most of the people who loathe him in the abstract would like him in the concrete. This is what makes him so strange and interesting. He weds an open, friendly, inclusive manner to a closed, hostile and exclusive set of policies. He is able to engage with everyone he meets but is nonetheless capable of demonizing just about every human being on the planet except for his mythic American working people. That is why he can sell his message; coming from him in the flesh it sounds almost friendly. There's some of Huey Long in his message and in him—he even looks a bit like the Kingfish—but he is different in one very important respect: he travels well. Huey outside Louisiana always seemed a bit of a buffoon. Not Pat.

By the time we arrive in the Tamworth Union Hall the blizzard has arrived, and there's a couple of inches of snow on the ground. It's getting dark, and for the past half an hour we have been the only cars on the road, wending our way on white highways through green pine forests dusted with fresh powder. Buchanan has delivered essentially the same speech five times in person and another half a dozen times on the radio. Instead of winding down he becomes more animated with each delivery. When you listen to Buchanan you have to remind yourself that normally people become tired of hearing themselves say the same thing over and over again. Even some politicians—Dole is a case in point—grow weary of their own beliefs. They stop speaking and start reciting. In Dole's case he has almost stopped speaking altogether. At some level, they cease to believe in what they are saying. Buchanan is just the opposite: he is more fully engaged with his views the tenth time he has offered them up than he is the first. It's one of the essential traits of the dogmatist that he acquires faith in himself through repetition.

Thirty people have somehow made their way to the town hall to hear him out. The sum total of political commitment in that one room already is greater than anything I've seen in the entire Dole campaign. Pat starts by poking fun at a 4-year-old boy in the front row who is yawning. The kid enjoys the attention; he hams it up, pretending to yawn for the next five minutes, but Buchanan has moved on. He's on fire, and no one is safe:

Not Bill Clinton: “The army is not his plaything. They aren't the Arkansas state troopers.” Not the Supreme Court: “The Supreme Court has usurped power and authority all across the country from the American middle class. Can you imagine what the Founding Fathers would have done if the Supreme Court had thrown out prayer from all the public schools? lock and load!” Not Ryutaro Hashimoto: “Who is this guy? I'll tell you who he is. This guy is a samurai warrior. He's cleaning Mickey Kantor's clock!” Not the Fortune Five Hundred: “Some of the biggest companies in America don't care about America. They care about profits. The company's got their loyalty, not their country.”

The only two of his usual villains that he misses are Mexicans and Pat Schroeder.

Once he lands on corporate America Buchanan has found his strongest theme: national socialism. Our companies are betraying our country, by which he means this mythic working-middle class of his imagination. As he lays into the rich, his Southern accent comes and goes. Now it comes: “AT&T lays off 40,000 workers. Did you see that? Well lemme tell ya. No one is lookin' out. No one gives a hoot. Clinton dudn't. And the Republicans dudn't.”

He grows hotter and hotter until he has arrived at his favorite moment. Suddenly, I know exactly what he's about to say. I've seen him say it before, and I have no doubt I will see him say it again. He's going to explain that the American working man needs Pat Buchanan because the only other guy in the whole country who even talks about his problems is ... a midget. Actually, he put it a bit more delicately: “Oh, yeah. There's Robert Reich down in the Labor Department. He's this ... little guy.” As he speaks he holds out his hand about three feet off the floor. “Reich talks about the problem, but he's not going to do anything about it.”

Everyone nods. No midget is qualified to deal with such a big problem. The people give Buchanan their grim approval. They nod and clap and purse their lips like they are determined to take charge of their country. I've seen that look before, through a thousand snowy windshields in Connecticut and Massachusetts and New Hampshire. These are the people who refuse to fly on airplanes when a bomb goes off but go hurtling through blizzards at seventy miles an hour. Pat makes them feel like they're back in control.