I have seen baseball’s past and it is in Baltimore, at Oriole Park at Camden Yards, the new $105.4 million ballpark where the local nine—the Orioles—are now in residence. Its predecessor, Memorial Stadium, was a nice enough and generally self-effacing spot for a ballgame. Camden Yards, on the other hand, promises to do for baseball stadiums what prewashing did for bluejeans.

Until quite recently, modern ballparks were notable for their retractable domed roofing, their synthetic sod and plastic seats, their sushi bars and Evian stands. But America, it turned out, craved something else entirely. Fans were wistful for ballparks where the ceiling is the stars, the grass grows, and peanut shells crackle under your feet. So after touring cities like Boston and Chicago, where the ballparks are old and the vendors hawk hot dogs, not veggie burgers, Baltimore’s stadium design team obliged with an instant antique.

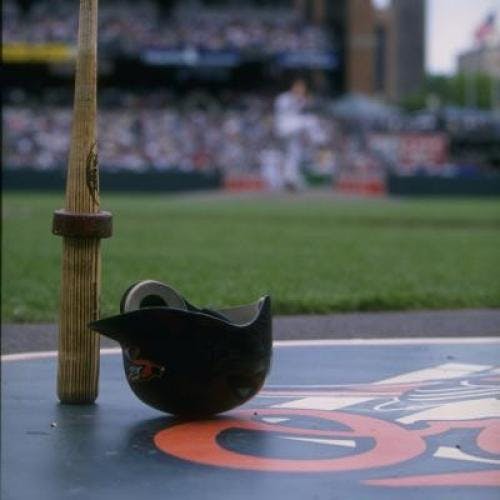

Camden Yards has all you might expect from a dowager ballpark, including an asymmetrical outfield, intimate porches, a red brick facade, 1920s Coca-Cola ads, ushers wearing bow ties and suspenders, and ornithologically correct aluminum “weather” orioles nesting atop the scoreboard. I have it on good authority that old-time baseball trivia is piped into the women’s restrooms. For backdrop, a gone-to-seed 1898 warehouse beyond the right field fence has been completely restored (it houses no wares and has been converted into a tony office building). This is, in short, the temple of retroball, a place, says New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger, “capable of wiping out in a single gesture fifty years of wretched stadium design.” Unfortunately, visitors to Camden Yards may be distracted by a flaw that hasn’t troubled the denizens of Boston’s Fenway Park (1912) or Chicago’s Wrigley Field (1914): from many of its spanking old slatted wooden seats, you can’t see much of the field.

Which is the problem. The beautification of baseball’s past and the consequent miasma of woolly commentary, mawkish sentiment, and cardboard portraits coveted—and priced—like Tintorettos is becoming more than a cultural fad. Partly in response, no doubt, to our increasingly fractured and fracturing society, a national pastime that has existed for the near breadth of our history is being turned into a social balm—and is being embalmed at the same time. Indeed, America is so swamped in baseball nostalgia that the game threatens to be obscured by a cloud of kitsch.

In the late 1980s baseball memorabilia first achieved truly stratospheric price levels. Unlike real estate prices, they haven’t dropped much since. The baseball Babe Ruth supposedly swatted for his sixtieth home run in 1927 just sold for $200,000 in San Francisco, and a flannel uniform shirt once worn by Mickey Mantle cost a reasonably sane-looking gentleman $111,000 in New York. (“Give him the pants,” someone in the audience bellowed when that deal was struck.) Baseball cards, which were once the passion of 10-year-olds, are now a serious commodity. The rarest of cards, a 1909 Honus Wagner, sold for $451,000 last year. More common stock, like a 1952 Mickey Mantle, goes for $30,000. Card shows are spiced by the appearance of a “legend,” old ballplayers like Ted Williams or Joe DiMaggio, who are hauled in for a few hours to sign anything put in front of them by long lines of people who have paid $50 to $100 for the privilege.

Many fans today seem disaffected with contemporary Major Leaguers who routinely command multi million-dollar contracts. Instead, they prefer to travel vast distances and spend large sums of their own to commune with men who hit and threw balls forty years ago. This coming winter, for $1,295, aficionados of the 1951 National League pennant race may sprawl on deck chairs on a cruise to Bermuda, within suntan-lotion-sniffing distance of the heroes of that autumn, ex-Giant Bobby Thomson and former Dodger Ralph Branca.

THIS OBSESSIVE NOSTALGIA is now permeating the broadest reaches of popular culture. Besides the glut of mainstream baseball history movies (Eight Men Out, Field of Dreams, The Babe, A League of Their Own), Ken Burns is following up “The Civil War” with a documentary history of baseball, due out in two years. American audiences have recently been treated to professional productions of an old-time baseball ballet in Pennsylvania, an opera in New York, and plays in Chicago, Boston, and off-Broadway. On the front of the current Wheaties box, you’ll see the face of Lou Gehrig, who died in 1941. There is a Nellie Fox Society in Chicago, a Burleigh Grimes museum in Wisconsin, and a Dizzy Dean Museum is thriving in Mississippi. The National Baseball Museum in the snug hamlet of Cooperstown, New York, had 373,793 visitors last year (compared with the 253,917 who went to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City). Just eight years ago only half that many made it to Coopers town.

“Old Timers Games,” painful exercises in which aged pros of summers long past gather in their knee breeches for a less-than-brisk three innings, have been gaining steadily in popularity. The idea of observing 61-year-old Willie Mays tottering after a pop fly or a 71-year-old Spec Shea serving up slowballs has proved so enticing to fans that every major league team now hosts an Old Timers Day. And so severe is baseball’s case of progeria that next year, in their debut National League seasons, the expansion Miami Marlins and Colorado Rockies will have them too.

The stylish American recreation of the moment is pre-baseball baseball. Teams playing 1858-rules “town ball,” which predated foul territory, used stakes rather than base sacks, and favored a soft, lumpy ball, are springing up around the country like dandelions in the outfield. And not long ago a warm-blooded collection of fanatics laced on their skates and took their swings (and their spills) on Mirror Lake in Lake Placid, just as Brooklynites did on the Capitoline Grounds back in the early 1860s, when baseball on ice was the rage. Indoors, meanwhile, on June 25, at U.S. District Court in Chicago, a group of prominent Illinois lawyers brandishing carefully overwrought summations staged a mock retrial of two of the notorious Chicago Black Sox, “Shoeless” Joe Jackson and Buck Weaver, who were banned from the pastime for allegedly consorting with gamblers to throw the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. Both ballplayers were acquitted this time, despite the efforts of their prosecutor, Tom Foran, who had better luck with the Chicago Seven in 1969. (The illiterate Jackson’s autograph, by the way, currently sells for $23,000, while Mozart’s signature fetches a mere $2,500 and Michelangelo’s but $2,250.)

Apparently the word in publishing is that if it’s about baseball, it sells, even if it reads as a dirt road drives just after a hurricane. Recent additions to the burgeoning baseball stock at my local bookshop include volumes investigating the premature deaths of “Big” Ed Delahanty (a slugger who disappeared from a train above Niagara Falls in 1903) and Ray Chapman (struck and killed by a fastball in 1920). Green Cathedrals, Lost Ballparks, and To Every Thing A Season are fresh dirges for old stadiums. Our Game, Baseball: The People’s Game and America’s National Game each lends its own spin to the saga of the early days. Diamonds Are Forever is the title of a catalog for a multimedia exhibition of backward-looking baseball art (well, some of it was art) that was displayed at the Houston Museum, the New York Public Library, and, among other places, at Cincinnati’s Contemporary Art Center, where it spent as many days as Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs. Baseball’s past is available on audiotape too, from a Connecticut company offering broadcasts of 1,000 different old ballgames at $13.95 a reel.

Vintage baseball attire is likewise in vogue. A man I know makes a reasonable living sewing antiquated baseball caps to order in the old cheese house behind his home in upstate New York. Major League Baseball is marketing a Cooperstown Collection, mass-produced souvenirs for defunct teams such as the St. Louis Browns and the Washington Senators, items that appear destined to make those teams more popular now than when they existed. Not to be outdone, some of the surviving franchises such as the Philadelphia Phillies and the Atlanta Braves are playing today in 1950s-style uniforms. Meanwhile, to complete the baseball outfit of today, a company in Nocona, Texas, manufactures 1930s-model baseball gloves and, for an extra fee, is willing to silkscreen an old ballpark such as Ebbets Field in Brooklyn onto the leather. This surfeit of baseball nostalgia would be harmless, of course, if it didn’t obscure the real pleasures of the game. But baseball, the game, faces twin dangers in the 1990s: of being turned into an instant televised entertainment and a homogenized nostalgic syrup. Both processes corrupt baseball’s essence. Unlike radio, which follows the natural pace of the game, the television camera decides what image you will see while the announcer tells you what to think about it. In its constant striving for attention, television brooks no perspective but its own. Unlike football, basketball, or hockey, baseball has no time clock hurrying the conclusion. Its natural rhythms and pauses do not easily correspond to advertising intervals or to frenetic MTV-style coverage. And it’s these pauses that offer the observer’s imagination the opportunity to knead what is seen so that an individual experience is carried home.

Similarly, baseball nostalgia undermines the authentic appreciation of a great game. It deprives the memory, flattens the past, and makes it generic rather than personal. It turns real memories into folklore; genuine stories into a design style; a real old stadium in to an instantly aged contrivance. And nostalgia undermines the true pleasures of baseball in a more obvious way as well. Old Timers games, baseball cards, and the rest are being taken for baseball when they are not that, but ancillary and vastly inferior games of their own, barnacles coating the hull of a handsome ship.

With luck, of course, the nostalgia craze may subside, along with our short attention span and current spasm of national insecurity. Just a few years ago the vagaries of style were skewed in the opposite direction. The 1970s were notable on the diamond for a forward looking approach to baseball: three-d baseball cards; white shoes; cookie-cutter concrete ballparks; waves in the stands; hyperelectronics on the scoreboard; golf carts in the bullpen; avant-garde uniforms featuring day-glo colors, and for the Chicago White Sox, a fleeting fancy—shorts. Baseball tolerates these permutations because they are peripheral. The game itself really doesn’t change very much.

Already there are faint signs that some people are forgetting how to remember. Barry Bonds, the Pittsburgh Pirates’ young left fielder and the son of Bobby Bonds, a fourteen-year major leaguer, took in the Old Timers game held the day before the All Star game in San Diego. The sight of Hall-of-Famers Bob Gibson and Bob Feller pitching to the likes of Ernie Banks and Reggie Jackson left him unimpressed. “I don’t know anything about this history stuff,” Barry sniffed afterward. “I failed history class.”

Nicholas Dawidoff, a special contributor at Sports Illustrated, is writing a biography of Moe Berg. This article appeared in the August 17, 1992, issue of the magazine.