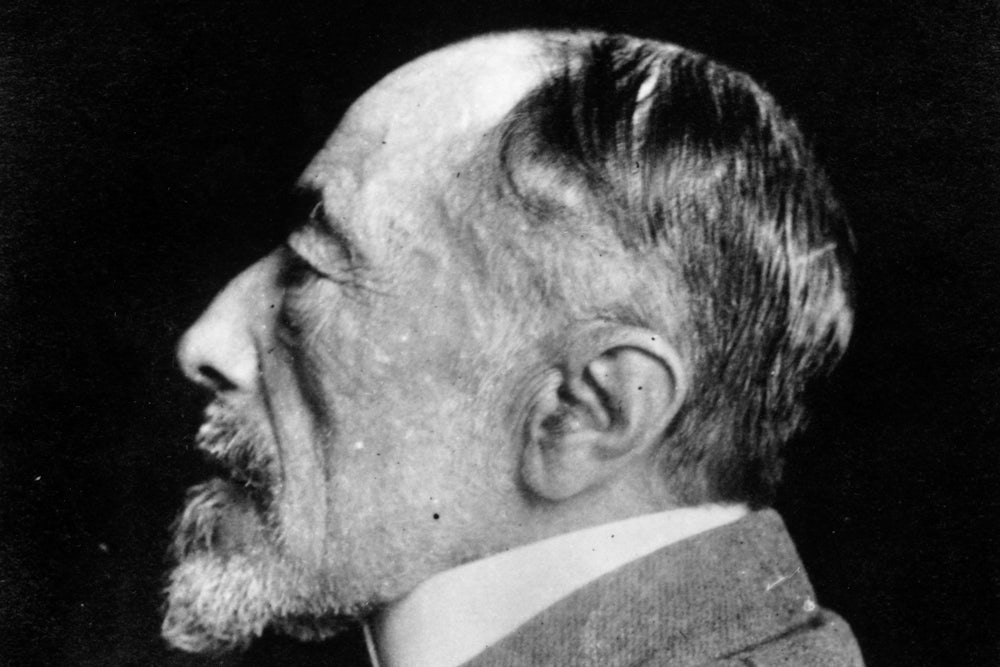

Among the great English novelists, Conrad most resists our understanding. There is sense in this. His largest theme is mystery, and the heart of all his greatest work is dark. He understood this early. “Marlow was not typical,” we read of the surrogate who narrates the first and most celebrated of his major works; “to him the meaning of an episode was not inside like a kernel but outside, enveloping the tale which brought it out only as a glow brings out a haze.” An empty center, then, surrounded by mist. I have studied Conrad for years, yet I perpetually feel, as I don’t with any other writer, that I am only just scratching the surface. Perhaps my mistake, as Conrad’s image suggests, is that I still believe that there is a hard or steady surface to scratch.

And what is true of the work, as E.M. Forster was the first to point out, is true of the man who made it. “Behind the smoke screen of his reticence there may be another obscurity,” Forster wrote, “preceding from ... the central chasm of his tremendous genius.” Another enveloping mist, another absent center. Conrad, who lived three lives--Pole, mariner, and writer--devoted the third to writing about the second and erasing the first. But he knew himself too well to believe in self-knowledge. “One’s own personality,” he wrote, “is only a ridiculous and aimless masquerade of something hopelessly unknown.” His own memoirs are anti-confessional: evasively genial, suspiciously neat, not to be trusted. Conrad did not understand himself, and did not pretend to understand himself, and did not expect to be understood.

Where does all this leave the biographer? In a fog, it seems. John Stape’s new life follows by a year the re-publication, in revised form, of the leading work in the field, Zdzisaw Najder’s Joseph Conrad: A Life. Najder’s study is the more thorough, Stape’s the more readable, but both have serious shortcomings, as does the other major biography, Frederick Robert Karl’s Joseph Conrad: The Three Lives, now almost thirty years old. Karl gets a lot wrong, and also promulgates all manner of Freudian improbabilities. Najder’s work, the result of half a century in the archives, is unimpeachable as to facts, but its interpretations are often vitiated by a rather free use of conjecture, a feeble textbook psychologizing, and--with respect to anything touching its subject’s land of origin--its author’s obvious but apparently unconscious Polish nationalism.

Stape’s study is written with wit and bounce, and with the kind of ironic worldliness that would seem to be a prerequisite for a biographer but which years of mole-work in research libraries are not inclined to foster. In a spirit of accessibility, he has kept his story short, but at less than three hundred pages, excluding appendices, it is too short. Stape can tell us, of Conrad’s collaboration with Ford Madox Ford, that the latter was supposed to act “as a goad on Conrad to produce, a kind of superior secretary with a stick, “ but that the first result, Romance, turned out to be mostly Ford “topped with a drizzle of Conrad.” Somehow he cannot find the space to mention that Ford later drafted a section of Nostromo, which many critics consider Conrad’s greatest achievement, to buy time during serialization while his friend lay incapacitated with depression. Conrad’s brilliant, despairing letters go largely unquoted, as do the many vivid descriptions his contemporaries left of him. Of literary appreciation, the book is similarly devoid: Heart of Darkness gets one wan sentence (“An artistic development of singular importance ... “). The last years of Conrad’s life go by in a welter of visits, illnesses, and royalties. The reader will finish Stape’s volume wondering what happened and what all the fuss is about. A truly satisfying biography of Conrad has yet to be written, and possibly never will be.

Joseph Conrad was born Teodor Jozef Konrad Nacz Korzeniowski into loss, self- division, and illusion--the very circumstances that thwart us in his life and work. The partition of his native land had been completed two generations before his birth in 1857, and there may have been no child of his time who was made to feel the condition of dispossession more acutely. His father, Apollo Korzeniowski, was a writer, and a dreamer, and a leading member of the “Reds,” the most radical faction of the Polish nationalist movement. The poem that he composed on the occasion of his son’s christening gives both the tenor of that movement--with its self-pity, its gloom, its spiritual hysteria, and its cult of the nation as martyr--and the weight of expectation thrust upon Conrad at birth. Titled “To My Son Born in the Eighty-Fifth Year of the Muscovite Oppression,” it reads in part:

Baby son, tell yourself

You are without land, without love,

Without country, without people,

While Poland--your Mother is

entombed.

This was Conrad’s patrimony, and the losses were just beginning.

The Russian yoke had always been the heaviest of the three partitioning empires’. Conrad’s family, living in what is now Ukraine, were Polish gentry--szlachta--amid Jews and Ruthenian peasants. When Conrad was three, his father moved to Warsaw to help organize the resistance movement that was to culminate in the pointless disaster of the Insurrection of 1863. Within five months, he had been imprisoned; within another eight, the Korzeniowskis had been exiled to the killing climate of the Russian north. Conrad’s mother was dead before his eighth birthday, his father before his twelfth. His childhood--he had no siblings-- was not only grim, it was also terribly lonely. “Konradek is of course neglected,” Apollo writes during his wife’s last illness. After her death, “he does not know what a contemporary playmate is.”

Whatever Conrad’s feelings at the time, his ultimate relationship to his father’s commitments was violently ambivalent. Under Western Eyes, the last of his great works and the one whose writing broke his spirit, expresses a loathing of Russian autocracy as a kind of vampiric force, but it also expresses a skepticism about revolutionary action as inevitably devolving into fanaticism and bad faith. Indeed, political idealism is put to examination in at least four of his five major novels--remember that Kurtz, too, is an idealist--and is seen in each to be at best naive and at worst monstrous. The ideological extremism that was the waxing power in European politics during the decades of Conrad’s career, and that he anatomized so acutely, had been his intimate acquaintance since childhood.

With his father’s death, a new influence came to bear. Tadeusz Bobrowski, a maternal uncle, took charge of Conrad’s upbringing. Bobrowski was everything his late brother-in-law was not: moderate, rational, practical. But though he tried to scrub Conrad of his Korzeniowski heritage, he could not prevent his nephew, when he was only sixteen, from indulging in the oldest of youthful fantasies by running away to sea. Of his decision to leave his family for Marseilles and the French merchant service, Conrad would later write that “I verily believe mine was the only case of a boy of my nationality and antecedents taking a, so to speak, standing jump out of his racial surroundings and associations.”

Like many of Conrad’s autobiographical statements, this must be taken as a poetic rather than a literal truth. As Stape points out, some three million Poles migrated westward between 1870 and 1914. But “standing jump” would have had a specific meaning in Conrad’s imagistic lexicon, evoking the moral crisis he had dramatized in Lord Jim. Jim’s breach of faith comes about precisely because he jumps overboard rather than standing at his post while serving as first mate on a ship that seems about to sink. A “standing jump” would appear to combine the two choices, the “standing” of fidelity and the “jump” of betrayal. But to what was Conrad faithful in jumping away from the national ties he would repeatedly be accused of having betrayed? To Polish romanticism itself. He forsook his father’s dream, but not his propensity for dreaming. Indeed, his awareness of this surely colors the fondness with which Jim, that dreamer, is presented. Marlow narrates that novel, too, and in his care for the younger man we can sense an older Conrad’s protective love for the boy he once was.

Conrad’s sea fiction and memoirs tend to mythologize his time at sea as so many years within a band of brothers devoted to the service of the British flag. The truth was more complicated and less happy. He left the French merchant fleet after a few years, not out of any sense that England was his destiny or her service the most noble, but because the far larger British fleet, in greater need of manpower, was more open to foreigners. Even so, the displacement of sail by steam, with its smaller crews, made work increasingly difficult to find. Conrad slowly rose through the ranks, but he was often forced to settle for jobs below his level of certification. In nineteen years at sea, eight of them as a qualified “master,” he captained only one ship.

The young szlachcic also bucked against the conditions of service. Time and again he would quit a berth after quarreling with his captain. His education and background would also have cut him off from the scrum of ruffians, drunks, and drifters who made up the typical crew. He is likely to have been no less lonely as a young adult than he had been as a child. On shore, he lived a life of culture and expense. Uncle Tadeusz, delivering a long series of final warnings, ceaselessly admonished his extravagance and just as unfailingly funded it. Conrad’s long periods ashore--he was afloat less than eight years altogether--were not always involuntary. Throughout his career, he plotted schemes of trade or investment as an alternative to further service; he gave up his only captaincy after little more than a year. His nearly two decades in the service were a series of false starts, and he seems never to have settled to life at sea. Only in retrospect did it assume shape, meaning, and value, and come to stand in his mind for fellowship and fidelity, duty and craft, labor and courage, honor and nation.

This last would prove especially important. A Personal Record, Conrad’s memoir of his youth, ends with his first glimpse of the Red Ensign, the flag of the British merchant service, “the symbolic, protecting warm bit of bunting flung wide upon the seas, and destined for so many years to be the only roof over my head.” His fiction consistently underplays the proportion of foreigners he encountered in the service, which on some voyages ranged as high as 60 percent. In The Nigger of the “Narcissus,” his most personal novel, only four of the sailors are foreign; in the real Narcissus, ten were--half the ship. Conrad’s retroactive reconstruction of an English service served his active construction of an English identity. But during his years at sea, as he wandered from Poland toward an unforeseeable destination, his identity was protean, and in many ways it always would be.

The spaces that Conrad knew--ships and waters alike--were as multinational as they were British. His crewmates were Russian, Scandinavian, and West Indian as well as Scottish and Cornish; his realms of service were the Dutch East Indies, French Antilles, and Belgian Congo, as well as India and Australia. While his French was impeccable, he spoke English, as he always would, with a thick Polish accent. His letters make use of all three languages and a variety of signatures. In fact, his name seems to have been the least stable thing about him, especially during his years at sea. A company of ghost selves floats across the life--nicknames, pseudonyms, garblings, alter egos: Konrad, Korzeniowski, Konkorzentowski, Korgemourki, Kamudi, Monsieur Georges, T. Conrad, H. Conrad, Johann Conrad, and in one instance, touchingly, Comrad. The list suggests a ship of many hands and many nations. Like Kurtz, all Europe contributed to his making.

Only when he steps ashore does the identity we recognize appear: “J. Conrad, “ used for the first time to sign off after what would prove to be his final voyage. By then he had undergone his most marvelous transformation of all. Conrad’s emergence as a writer has no parallel in English literature, perhaps not in any literature. George Eliot was also thirty-seven years old when she published her first work of fiction, but she was already an accomplished essayist, and she moved in the highest intellectual circles. Nabokov, too, was a foreigner, but he had known English from early childhood, and he had already mastered the art of fiction before taking up the language as a literary instrument. Conrad had both their disadvantages and many others. When he began drafting Almayer’s Folly one idle autumn, five years and four voyages before it was ultimately finished, he was an unknown seaman who had written almost nothing more ambitious than a letter, and he was venturing into a language that he had not started to learn until he was twenty.

Then as now, there was no shortage of obscurities nursing dreams of literary greatness, dragging their manuscript along from year to year. Conrad just happened to turn out to be a genius. “There is more--and different things too--in me yet,” he could still declare at fifty. If he was skeptical about the possibility of self-knowledge, that must have been in part because he had experienced the mysterious depths of his own powers.

Conrad would eventually make art out of large areas of his life at sea, but one experience in particular incited him to fiction. In 1887, during his longest stint in the East, he spent four months sailing in Borneo and Celebes, the remotest parts of the Malay Archipelago. It was his first close look at the East, beyond the bubble of large Europeanized ports such as Bombay, Singapore, and Sydney. His voyages took him sometimes as much as thirty miles upriver, to far-flung trading posts set down amid a bewildering complexity of local cultures and dwarfed by their backdrop of jungle and fog. There Conrad stumbled upon the sea wrack of colonial civilization: idlers and adventurers, scoundrels and cranks, lost, lonely men who dreamed of Europe and wealth and consoled themselves with native women and the bottle. In them he recognized what was to become his most enduring theme: moral isolation.

Even more than imperial rapacity or spiritual extremism, more than fidelity or toil or unrest, this is the red thread that runs through Conrad’s greatest work and makes it a supreme expression of his time, which is still our time. Moral isolation--the sense of being without companionship, without even comprehension, in the perilous business of choice--marks his characters’ existence for the same reason that it marked his own. The worlds of Conrad’s fiction are shaped by imperialism, but they are not, by and large, imperial spaces. Forster, by contrast, gives us in A Passage to India the more typical colonial situation: two communities, European and native, living in precisely defined relations of subjugation and power, the lines of allegiance and conduct carefully laid down. Conrad’s attention was drawn instead to the spaces between empires, between nations, the kinds of spaces in which he had passed his nautical career--intercultural spaces, permeated by the force fields of empire but not bound within a single imperial orbit: the Malay world of his early fiction, the Inner Station of Kurtz’s domain, the republic of Costaguana in Nostromo, the anarchist cell in The Secret Agent, the circle of Russian exiles in Under Western Eyes. Each is made up of individuals who have lost the orientation of a familiar community and the restraining context of a stable moral framework. (His sea fiction, stories of fellowship and fidelity within a known horizon of expectation, gives the complementary perspective, a picture of the world that has been lost.)

This is not Dickens’s London, an earlier and more bounded kind of modern space, domestic rather than imperial, where isolation and incomprehension finally give way to recognition and communion. In Conrad’s world of expatriates and isolatoes, mutual estrangement is intractable, cultural fragmentation is irreparable, and neither authorial prestidigitation nor English good fellowship can relieve them. His characters cling instead to shards of broken meaning--a name, an idea, a dream. Each is left alone with his impulses and terrors and illusions, armed only with a fragile sense of right and wrong.

By the time he got to Borneo, Conrad was already several times an exile and many years a wanderer, and what he discovered must have resonated powerfully with his own experience, for he began composing Almayer’s Folly, set in an upriver trading post and concerned with the type of man he had found there, upon his next return to England. Flaubert and Maupassant, long his reading, were now his models. Timely encouragement came from a Cambridge graduate to whom he showed the growing manuscript while serving aboard a passenger ship. Conrad was a man of culture and a writer’s son, and he hungered for contact with the world of letters. His turn to fiction must have felt like a kind of homecoming--perhaps the only one he ever had.

Conrad’s first works, shepherded by his editor Edward Garnett, a well- connected member of the literary world, were well received but modestly remunerated. Conrad would vacillate for years about returning to sea, but for the time being he pressed on. Meanwhile, through Garnett and a few other acquaintances, he groped his way into English life, constructing that masquerade of personality that he called “Joseph Conrad.” His sense of alienation can be gleaned from “Amy Foster,” the brilliant story he would soon write, in which a European castaway on English shores is met with uncomprehending hostility, viewed as a kind of gibbering monster. In person, Conrad could neither hide his accent nor conjure away his foreign looks, but print made for a better place to bury secrets. With a single, slight exception, his fiction would never give the faintest hint of his Polish background. In his first two novels--the name of the second, An Outcast of the Islands, suggests its continuity of setting and theme with the first--nothing directly reveals even his nautical one.

“When speaking, writing or thinking in English,” Conrad had written as early as 1885, “the word Home always means for me the hospitable shores of Great Britain.” The initial qualification is telling, given that Conrad often spoke, wrote, and thought in other languages. Equally telling is the generic nature of his imagined home: Great Britain in general, but not any particular place in it. Conrad had long yearned to find himself a specific English home, and in 1896, immediately after the publication of An Outcast--whose title can be read in more than one way--he made a precipitous jump into English domesticity, marrying an undereducated working-class woman he seems scarcely to have known. He was thirty-eight, Jesse George was twenty-three.

The record of Conrad’s erotic life, both before and after his marriage, is exceedingly thin. Sexuality seems to have been a less potent force for him than his desire for friendship--this is perhaps another reason we find him so difficult to understand. The Conrads settled in the countryside, near Ford, Stephen Crane, H.G. Wells, and other members of his growing circle. His fiction, too, moves toward comradeship and, haltingly, toward self-revelation. The Nigger of the “Narcissus” finally takes up his nautical experiences directly, but the novel is troubled by Conrad’s difficulty in locating himself in relation to the shipboard community whose unself-conscious fellowship it depicts. He seems to have been unable to figure out how he wanted to appear before his English audience. His struggles with identity had become an impediment to his art. The answer that he discovered was not to place himself-- not even his “Joseph Conrad” self--as a narrating presence within his fiction. The answer was to invent yet another persona, comfortably nautical and solidly English, with his own circle of friends and listeners. The answer was Marlow.

Marlow unlocked the door to Conrad’s major work, helping him produce, in the space of two years, “Youth,” the first of his great short stories; Heart of Darkness; and Lord Jim. The second of these is not his most ambitious work, and arguably not even his greatest, but it will surely be the one by which he is longest remembered. A long string of imitations and counter-versions--by Wells, V.S. Naipaul, António Lobos Antunes, James Dickey, Caryl Phillips, Francis Ford Coppola, and many others--has ratified its canonical, or we might say (adopting a term coined for The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, that other river journey) its hyper-canonical status. Like Robinson Crusoe or Kafka’s “Metamorphosis,” Heart of Darkness achieves its transcendent stature by approaching the condition of myth. Indeed, like Ulysses or The Waste Land, though far less laboriously than those other modernist masterworks, it compresses a whole set of myths into a single narrative substance. The voyage of exploration, the heroic quest, the epic descent, the journey into the self: all are implicit in Marlow’s odyssey.

But Heart of Darkness has itself become a foundational modern myth by registering some of the chief anxieties of its historical moment. The menace that Marlow senses emanating from the jungle is a projection of his own guilt. He knows that he is going somewhere he does not belong, and he senses that the universe will intervene to restore the violated balance. The history of literary travel, whether of wandering, discovery, or conquest, holds no precedent for this intimation; in Conrad’s consciousness, imperial expansion reached the limit of its own self-revulsion. That is what has made his tale so adaptable to Dickey’s Appalachia, Coppola’s Vietnam, and every other scene of neo-colonial intrusion.

Marlow returns to England a post-traumatic husk, and his confessions parallel Freud’s development of the psychoanalytic monologue as a path into the darkness of the human heart. But the imperial system that he had discovered in the Congo resembles nothing so much as a parody of Weberian bureaucracy, another key theoretical articulation of the time. What Marlow finds among the accountants and the managers, with their “methods” and their bookkeeping and their reports, is procedural rationality run mad. The “cannibals” who man his steamboat are paid not in anything they can eat or trade, but in lengths of utterly useless copper wire--but they are paid, Marlow acknowledges, “with a regularity worthy of a large and honorable trading company.”

The double reach, toward Freud and Weber, psyche and society, is characteristic of all Conrad’s major work, and places him at the pivot point between the great social chronicles of the nineteenth century and the great psychological explorations of high modernism. He achieves the depth of the one without sacrificing the breadth of the other. And the place where the two orientations meet, where Weberian corruption becomes Freudian revelation, is language. Marlow asks the chief accountant how he manages to sport such clean linen in the midst of the jungle. “I’ve been teaching one of the native women,” the accountant explains. “It was difficult. She had a distaste for the work.” The last phrase points straight toward Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language,” toward “collateral damage” and “extraordinary rendition” and “enhanced interrogation techniques.” As always, its real purpose is not deception but self-deception, the disabling of the ethical gag-reflex.

Moral isolation is only the first step in the Conradian descent. His characters are strangers to one another, especially to those with whom they are most intimate, but above all they are strangers to themselves. Because they have been stripped of an encircling community, the only ideas that matter to them are the ones they have about themselves, and they can have any ones they want. Apocalypse Now is a profound gloss on the novel, but it simplifies Conrad’s scheme by making Kurtz too glibly cynical, too comfortable with his own damnation. The original Kurtz, self-divided and self-deluded, hugs his fantasies to the last. That is finally what makes him such a supreme symbol of the modern soul, holed up in his Inner Station, ensconced in the throne room of his imperial self. Moral isolation is exactly what he wants, because it leaves him free to dream the dream of himself undisturbed.

To the decay of language and the gravitational force of self-delusion Conrad opposed the powers of literary art. “The conquest of the earth,” Marlow famously says, “is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much.” But Conrad’s mission--as quixotic a venture as running away to sea, and equally true to his father’s spirit--was precisely to “look into it too much.” “My task, “ he wrote in the Preface to The Nigger of the “Narcissus,” his declaration of artistic purpose, “is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel--it is, before all, to make you see.” Conrad may be the most visual of novelists, staging his lighting effects with the precision of a master cinematographer: candlelight, lamplight, blinding sunlight; shadow, gloom, and a dozen varieties of haze. An exquisite precision both of visual perception and verbal expression marks his narrative style, a disillusioned irony casting everywhere its cold illumination. “The reaches opened before us and closed behind,” Marlow says, “as if the forest had stepped leisurely across the water to bar the way for our return.”

Writing like that does not come without sweat and tears; for someone composing in a foreign language, it does not come without blood. Conrad’s agonies rival Flaubert’s, and his letters are some of the most colorful in the annals of writerly suffering. He is “lonely as a mole, burrowing, burrowing without break or rest”; he is “like a cornered rat, facing fate with a big stick that is sure to descend and crack my skull”; he is alone with a monster “in a chasm with perpendicular sides of black basalt”; he is about to be “ingloriously devoured” by “an irresistible march of black beetles”; he is trapped in “a kind of tomb which is also hell where one must write, write, write.” He was writing against time--serialization deadlines, promises to agents and editors--and in the face of illness and money trouble. He suffered constantly from gout and depression. Jesse was no healthier, undergoing an endless series of operations to repair an injured knee whose condition was not improved by her steadily increasing obesity. The couple also had two sons. Flaubert could afford to spend six or eight years on a novel, but Conrad turned out nearly a book a year, including short stories and prose sketches, and still grew deeper in debt. He was no better at handling money than he had been as a bachelor.

Jesse was scorned by more sophisticated women--Virginia Woolf called her a “lump,” Lady Ottoline Morrell a “mattress”--but she was plucky and gregarious, and she kept the household together. Yet she couldn’t do anything about Conrad’s writing schedule, which was always hopelessly disorganized. He was the kind of person who used one project to procrastinate on another. Heart of Darkness interrupted the writing of Lord Jim, which had itself interrupted the writing of The Rescue, a book that finally took Conrad twenty-four years to wrestle to the ground. Almost every one of his novels began life as a short story before expanding beyond all prediction. Of course, another way to see this is that Conrad was willing to let himself be taken by surprise, and was smart enough to trust his intuition and let the deadlines be damned.

There was always more--and different things, too--in him yet. After Heart of Darkness, which must have given him an entirely new idea about what he could do, about what there was to do, he returned to Lord Jim, put Marlow at its center, and amid the pressure of serialization produced a novel that, in its fragmentation of linear sequence and its orchestration of competing narrative modes, represents English fiction’s great leap forward into modernist complexity. After Lord Jim and a third volume of short stories (there would be six altogether), he felt that he had exhausted his experiences as a subject of fiction. “It seemed somehow,” he would later note, “that there was nothing more in the world to write about.” And then he remembered a little anecdote about a man who had stolen a boatful of silver, and within two years he had built the republic of Costaguana, and the pseudo-historical epic Nostromo, brick by brick.

His imagination, proving even deeper than he had imagined, had undergone a fundamental change. He had come to understand that he no longer needed to rely on his own experience as a source of material-- another reason that biography is so helpless before his art. The Secret Agent, with its caustic irony and bitter skepticism, and Under Western Eyes, with its Dostoevskian tensions, would complete the trio of great political novels. But the three were not just unforeseeably different from his earlier work. Each of them--indeed, each of his five major novels--is radically different from all the others: in subject, in structure, in tone, even in style. It was not enough for him to reinvent himself as a writer after his career at sea. Fidelity to his sense of artistic vocation required him to re-invent himself again every time he sat down to write.

If his peers were in awe, the public was less impressed. Even before Nostromo, figures such as Edward Garnett, Edmund Gosse, and George Gissing had come to regard Conrad as the finest novelist of his generation. Henry James was genuinely admiring. But Wells had warned him early that “you don’t make the slightest concessions to the reading young woman who makes or mars the fortunes of authors.” Conrad proudly ignored the advice. Of “The Secret Sharer,” another of his great short works, he would boast that it contained “no damned tricks with girls.” But tricks with girls-- romantic interest, as scarce in his major work as it is in the record of his life--was exactly what the reading young woman, and most other book buyers, wanted. Conrad’s darkness and difficulty repelled them, and he refused to play the game of advertising and publicity.

He had fewer qualms about borrowing money from his agent, James B. Pinker, who, like Garnett, became a kind of father figure, even though both men were considerably younger than he. Finally, after years of patience and mounting subsidies, and just as Conrad had finished dragging himself through Under Western Eyes, Pinker put his foot down: no more loans. The ultimatum precipitated a nervous collapse unlike anything even Conrad had ever known. He raved in Polish, held imaginary conversation with his characters, and didn’t emerge from prostration for three months.

When he did, he was a broken man. With scant exception, the work Conrad produced over the last fourteen years of his life is frankly second-rate, and even worse. He simply no longer had the moral energy left for the terrible daily struggle with words. For the first time in his career, in fact, he was able to write with ease, and he started filling his novels with tricks with girls. And so, in the wryest twist of all, he became a success. He finally wrote badly enough to attract a mass audience. Meanwhile the popular press had caught up with the judgments that more perceptive critics had been advancing for years. By the time he gained fame, as is often the case, his best years were behind him, and his late mediocrities fetched many times the price of, and much louder a volume of praise than, his finest works.

Success made Conrad wealthy, but it never made him easy. He spent money almost as fast as it came in, his failing powers tormented him, his wretched health persisted to the end. His towering achievement would make Joyce envious and Nabokov nervous, but for the aspiring writer, his example braces and terrifies in equal measure. It is never too late to begin, his story tells us, but there is no limit to what you will be asked to surrender. You may reach the Inner Station, but do not expect to make it back.

William Deresiewicz is the author of Jane Austen and the Romantic Poets (Columbia University Press).