I have liked John McCain ever since I met him almost a decade ago. At the time, I was writing a profile of then-Senator Fred Thompson, who was rumored to be considering a run for the presidency. I had been playing phone tag with the press secretaries of senators friendly with Thompson and was getting nowhere. I decided that, instead of calling McCain’s office, I would drop by. I spoke to one of his aides, who asked me whether I had time to see the senator then. To my amazement, I was ushered into McCain’s office, where, without staffers present, he answered my questions about Thompson.

Talking to a senator in this manner, and on such short notice, is unheard of in Washington. Senators like to stand on ceremony, and they also like to surround themselves with solicitous and protective aides. But McCain is different. It is a difference that he refined after being caught up in the Keating Five scandal in the early ‘90s, but it fits his personality and jibes with his public-minded advocacy of campaign finance reform.

McCain is also another rarity in Washington: a centrist by conviction rather than by design. His political philosophy places him closer to Theodore Roosevelt than to his other idols, Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan: more noblesse oblige than libertarian populism or business conservatism. He says he favors “a minimum of government regulation in our lives,” but what really matters is whether a policy or business practice is in the national interest. If it isn’t, he’ll use the power of the government to change it. Goldwater would not have voted for a bill tightening controls over the tobacco industry, and Reagan would have balked at curbing pollution. McCain has backed both. Liberals have recently chided him for wooing his party’s evangelical base, but these have been nominal efforts. McCain pronounced himself in favor of teaching creationism as a theory; but he also devotes a chapter of his latest book to the genius of Charles Darwin. He gave a commencement speech at Jerry Falwell’s Liberty University; but, in a subtle rebuke to Christian conservatives, he spoke entirely about foreign policy. Earlier this year, he voted to block a constitutional amendment banning gay marriage.

McCain’s idiosyncratic approach to party politics also makes him an outlier. His commitment to bipartisanship is real--he worked with Russ Feingold on campaign finance reform, Ted Kennedy on immigration reform, and Joe Lieberman on global warming--as is his relish for battling his own party’s leaders. Last month, when Bush and his congressional allies were using a bill flouting the Geneva Conventions to paint Democrats as soft on terrorism, McCain, along with John Warner and Lindsey Graham, blocked the measure and insisted on a compromise. True, the compromise was flawed. Still, it undermined the administration’s efforts to exploit the war on terrorism for political purposes.

McCain has one other attribute that separates him from many of his peers in Washington: He is willing to change his mind. This may be his most admirable quality; yet it is also frequently overlooked, probably because it seems to contradict McCain’s reputation for stubbornness, even nastiness--a reputation his right-wing opponents are all too happy to speculate about. “Everyone knows McCain has a temperament problem, but no one is going to say anything about it,” one prominent Washington conservative complains. Yet the most distinctive aspect of McCain’s temperament is not his anger; rather, it is his penchant for reconsidering both old enmities and old convictions. Witness his work with John Kerry on normalizing relations with Vietnam, as well as his collaboration on campaign finance reform with activist Fred Wertheimer, who had sharply criticized McCain during the Keating Five scandal.

Nowhere has McCain’s willingness to question his own previous assumptions been more dramatic than on foreign policy. When he first arrived in Washington, he was essentially a realist, arguing that U.S. military power should only be used to protect vital national interests. Since the late ‘90s, however, he has joined forces with neoconservatives to support a crusade aimed at overthrowing hostile and undemocratic regimes--by force, if necessary--and installing in their place democratic, pro-American governments. Unlike many Republicans, he enthusiastically backed Bill Clinton’s intervention in Kosovo. Moreover, he was pushing for Saddam Hussein’s forcible overthrow years before September 11--at a time when George W. Bush was still warning against the arrogant use of American might.

And therein lies my McCain dilemma--and, perhaps, yours. If, like me, you believe that the war in Iraq has been an unmitigated disaster, then you are likely disturbed by McCain’s early and continuing support for it--indeed, he advocates sending more troops to that strife-torn land--and by his advocacy of an approach to Iran that could lead to another fruitless war. At the same time, he has shown an admirable willingness to reevalute his views when events have proved them wrong. The question, then, comes down to this: Is John McCain capable of changing his mind about a subject very close to his heart--again?

To begin to answer that question, you have to understand McCain’s philosophical evolution on foreign policy. Not surprisingly, that evolution has everything to do with Vietnam.

McCain comes from a long line of military men. His father and grandfather were both four-star admirals. Attempting to follow in their footsteps, McCain attended Annapolis and, after graduating in 1958, became a naval aviator. By his own admission, he was brash, sometimes insubordinate--a maverick within a profession grounded in hierarchy. He longed to prove himself by going to war. Having absorbed his father and grandfather’s stories about World War II, he had no doubt that the United States would triumph. “I believed that militarily we could prevail in whatever conflict we were involved in,” he told me.

McCain also acquired from his father a particular view of American power. The elder McCain admired the British Empire and conceived of the United States playing an analogous role in world affairs. In 1965, he commanded the U.S. invasion of the Dominican Republic, which blocked a previously ousted government--one that the Johnson administration believed was too friendly with Fidel Castro--from regaining power. The invasion was unpopular in both the United States and the Dominican Republic; but, afterwards, McCain’s father said, “People may not love you for being strong when you have to be, but they respect you for it and learn to behave themselves when you are.”

McCain’s faith in this approach would be tested in Vietnam. He began bombing runs over North Vietnam in mid-1967, at a time when the Johnson administration was restricting the targets American pilots could hit. McCain soon became disillusioned with this strategy. He and his fellow pilots regarded their civilian leaders as “complete idiots” who “didn’t have the least notion of what it took to win the war.” In October 1967, McCain was shot down over Hanoi. He was imprisoned and tortured for five and a half years, and he emerged thoroughly chastened in his views on war and American might.

Like his father, who commanded U.S. forces in the Pacific during the last years of the Vietnam war, McCain continued to defend the decision to intervene--most notably in an article he wrote for U.S. News & World Report after his release--but he took a fairly narrow view of when wars were worth fighting. During a year spent studying the origins of the Vietnam conflict at the National War College, McCain began to develop a version of what would later be called the Powell Doctrine. He insisted that any intervention had to be demonstrably in the national interest, and he defined national interest in a limited way. Resisting global communism qualified; overthrowing brutal tyrannies or rescuing their victims did not. “The American people and Congress now appreciate that we are neither omniscient nor omnipotent,” McCain would later tell the Los Angeles Times, “and they are not prepared to commit U.S. troops to combat unless there is a clear U.S. national security interest involved. If we do become involved in combat, that involvement must be of relatively short duration and must be readily explained to the man in the street in one or two sentences.”

The McCain who arrived in Washington in 1983, after winning a House seat from Arizona, was still a hawk, but a very cautious one. He had abandoned the gung-ho idealism of the early cold war for a more tempered realism. And the U.S. defeat in Vietnam was still very much on his mind.

McCain’s first application of his newfound realism came in September 1983, when he had to vote on a bill to extend the U.S. military presence in Lebanon. A year earlier, in the wake of Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, the Reagan administration had sent Marines to Beirut to help oversee the evacuation of the Palestine Liberation Organization. But the Marines had lingered in Lebanon to aid the new government, which was fighting local militias as well as Syrian forces. Republican and Democratic leaders lined up in favor of extending the U.S. stay there, but the freshman McCain, to their displeasure, declared his opposition.

McCain called for a gradual U.S. withdrawal from Lebanon. He argued that there were not enough U.S. forces to protect the government. The United States could introduce more troops, he said, but that wouldn’t be justified because there was no “clear U.S. interest at stake.” McCain’s concerns, of course, proved prescient--a month later, suicide bombers blew up Marine barracks in Beirut, killing 241 Americans and forcing a U.S. withdrawal--but, at the time of the September vote, his stance brought him only grief as Republican leaders, infuriated by his dissent, snubbed him in the halls.

The second major challenge to McCain’s post-Vietnam worldview came when Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990. McCain, who had been elected to the Senate in 1986, shared the Bush administration’s determination to protect Saudi Arabia and oust Iraqi forces from Kuwait. But, in the beginning, McCain played the cautious realist. He was concerned primarily about Saddam Hussein monopolizing the region’s oil, and he was initially skeptical of the need to use U.S. ground forces. “I think that we have got to make use of the advantages that we have, and that is through the air,” he told Judy Woodruff in early August. Later that month, he warned in a Los Angeles Times interview, “If you get involved in a major ground war in the Saudi desert, I think support will erode significantly. Nor should it be supported. We cannot even contemplate, in my view, trading American blood for Iraqi blood.”

During Clinton’s first term, McCain remained wary of sending troops overseas. He called for bringing U.S. forces home from Somalia and opposed intervening in Haiti. He also backed the administration’s initial refusal to commit forces to Bosnia, where Serbs were engaged in a campaign of ethnic cleansing against the Muslim and Croat populations. McCain argued that, because the conflict did not bear on America’s “vital national interests,” it did not justify the use of force. Moreover, McCain doubted whether American power could really do any good in Bosnia. U.S. efforts in the Balkans, he lamented in May 1995, were “doomed to failure from the beginning, when we believed that we could keep peace in a place where there was no peace.”

Given McCain’s stance on Bosnia, one might have expected him to caution Clinton to stay out of Kosovo as well. Instead, by October 1998--five months before nato would begin bombing Serbia in response to atrocities committed in Kosovo--McCain was telling CNN that he was “not in opposition to taking military action” to deal with a “humanitarian problem here of tens of thousands of innocent people dying.” What had changed?

McCain’s evolution did not take place overnight. According to people close to him, the senator’s outlook had begun to shift in the early ‘90s, when he started to take an interest in democracy promotion and human rights. In 1993, McCain became chairman of the International Republican Institute, a government-funded group that promotes democracy and capitalism overseas. “We were all intoxicated by the fall of the Soviet Union and the collapse of its empire,” he says.

There was another factor, too. Haunted by the American defeat in Vietnam, McCain had been reluctant to see troops deployed abroad. But his brother Joe says that the American victory in the first Gulf war restored the senator’s confidence in U.S. power, allowing him to again contemplate military interventions. “Once the chess pieces were back on the board, then he thought he would play chess,” Joe McCain says.

And then there was the shock of Srebrenica, where Serb forces murdered thousands of Bosnians in July 1995. Its full impact on his worldview may not have been immediate, but, today, McCain recalls the massacre as a key moment in his evolution on foreign policy. “My reluctance was eradicated by Srebrenica,” he says. “I was belatedly aware of the terrible things going on there and that the only way we were going to solve it was militarily.”

Yet, for a time, McCain held back, possibly because he lacked confidence in the Clinton administration. Days after Srebrenica, he said, “We cannot make a plausible argument to the American people that our security is so gravely threatened in Bosnia that it requires the sacrifice, in great numbers, of our sons and daughters to defend.” When the Clinton administration successfully negotiated the Dayton peace accords in November, McCain initially opposed sending American peacekeepers to help enforce it. After Clinton promised the troops without consulting Congress, McCain relented and supported efforts to secure funding. Still, he joined other Republicans in insisting that U.S. forces in Bosnia have an “exit strategy” and not engage in “nation building.”

But that was the last time McCain would express significant skepticism about U.S. intervention. By 1997, his friend William Cohen was secretary of defense, and McCain was, to paraphrase his brother, ready to play chess. The first visible sign of a change in McCain’s worldview came on Iraq. During the first Gulf war, McCain had backed President Bush’s decision not to advance on Baghdad. But, in November 1997, he announced on Fox News that it had been a mistake not to oust Saddam during the war, and he called upon the Clinton administration to set up an Iraqi government in exile. The following fall--in the face of opposition from both the Pentagon and the State Department--McCain co-sponsored the Iraq Liberation Act, which committed the United States to overthrowing Saddam’s regime and to funding opposition groups. McCain welcomed Ahmed Chalabi, leader of the Iraqi National Congress (INC), to Washington and pressured the administration to give him money. When General Anthony Zinni cast doubt upon the effectiveness of the Iraqi opposition, McCain rebuked him at a hearing of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

The second, and perhaps clearest, indication that McCain was changing his outlook came in his response to the crisis in Kosovo. As in Bosnia, Serb forces were committing ethnic cleansing and atrocities but did not pose a direct military or economic threat to the United States. Yet, this time, when McCain chided Clinton, it was for using American power too cautiously. “The president of the United States,” he said in May 1999, “is prepared to lose a war rather than do the hard work, the politically risky work, of fighting it as the leader of the greatest nation on Earth should fight when our interests and our values are imperiled.” Note the word “values” alongside the word “interests.” Clearly, this was a new McCain.

To be sure, Vietnam still loomed large in his worldview. But the shadow of defeat in Vietnam had lifted, allowing McCain to regain the expansive view of America’s power and responsibility that he had inherited from his father. McCain was still using the example of Vietnam, but to argue for bolder--rather than more cautious--application of U.S. power. “We’re now seeing things that are echoes of the Vietnam war,” he complained in April 1999. “Targets being selected by the president of the United States; restraints on where and when we hit those targets; and, perhaps most importantly of all, an outright commitment that we will not use ground troops as necessary.”

He also dropped his opposition to open-ended commitment of U.S. troops and to nation-building, which, for most Republicans, had become synonymous with everything that was wrong with Clinton’s foreign policy. “Despite the unacceptable circumstances of the weak and endangered peace in Kosovo,” he said on the Senate floor in March 2000, “it is infinitely preferable to the widespread atrocities committed during the course of Serbian aggression, atrocities that would surely reoccur were nato to fail in our current mission.”

McCain’s position made sense. If U.S. forces could prevent atrocities without becoming bogged down in a long war and occupation, why shouldn’t they? And, if they could encourage more democratic forms of government, why not do that as well? But what succeeded in Kosovo--where the United States was intervening as part of nato and had no intention of single-handedly occupying and running a country--would not work everywhere. Iraq would soon expose the perils of an overly aggressive idealism. Which is where my qualms with the new McCain begin.

Until the late ‘90s, McCain’s foreign policy consisted largely of lessons from the past that he applied on a piecemeal basis. In 1998, when The Weekly Standard asked what kind of foreign policy he would practice if elected president, he responded, “The first thing I’d do is convene the best minds I know of in the field of foreign policy, and that would include members of previous Democratic and Republican administrations. I’d have [Zbigniew] Brzezinski, Jim Baker, [Brent] Scowcroft, Tom Pickering, [Henry] Kissinger, Warren Christopher--and I’m sure others. I’d say, `Look, let’s figure out where we are, where we need to go, what our conceptual framework is. Let’s work out a cohesive foreign policy.’” That wasn’t much of an answer.

But, in the months and years that followed, McCain, seeking to differentiate his views from those of other Republican presidential aspirants and from the growing isolationism of House Republicans, would place his new interventionist instincts within a larger ideological framework. That ideological framework was neoconservatism. McCain began reading The Weekly Standard and conferring with its editors, particularly Bill Kristol. Kristol is predictably modest about his influence on the Arizona senator, although he acknowledges, “I talked to McCain on the phone and compared notes.” But when McCain wanted to hire a new legislative aide, his chief of staff, Mark Salter--himself a former aide to neoconservative Jeane Kirkpatrick--consulted with Kristol, who recommended a young protege named Daniel McKivergan. Marshall Wittmann, one of Kristol’s closest friends, became a key adviser during McCain’s presidential campaign. Randy Scheunemann, who had drafted the Iraq Liberation Act and was on the board of Kristol’s Project for a New American Century, became McCain’s foreign policy adviser. One person who has worked closely with Kristol says of Kristol and McCain, “They are exceptionally, exceptionally close.”

The senator’s embrace of neoconservatism was accompanied by a reevaluation of his childhood hero, Theodore Roosevelt. McCain had long admired Roosevelt’s adventurous spirit, but Kristol--as well as other neoconservative writers like Robert Kagan and David Brooks--was busy building the former president into something more: a model for “national greatness conservatism,” a philosophy that linked the development of American character to the exercise of power overseas. Wittmann, a Roosevelt devotee who currently runs a website called The Bull Moose, gave McCain pieces by Kristol, Kagan, and Brooks on Roosevelt, as well as writings by Roosevelt himself. McCain began referring to Roosevelt in interviews, and Wittmann and Salter began working Rooseveltian themes into his speeches. The result was a growing emphasis on America’s responsibility to transform the world.

McCain unveiled his new approach in a March 1999 speech at Kansas State University. The speech--which Wittmann, Salter, and Scheunemann all contributed to--echoed neoconservative themes. Long gone was the McCain who had worried about U.S. overreach. “The United States is the indispensable nation because we have proven to be the greatest force for good in human history,” McCain said, adding that “we have every intention of continuing to use our primacy in world affairs for humanity’s benefit.” In an earlier essay, Kristol and Kagan had described Republican isolationism as “pinched.” McCain now described it as “cramped.” The centerpiece of the speech was a strategy that McCain called “rogue-state rollback.” Scheunemann says he invented the term, adapting it from the conservative critics of 1950s cold war containment. According to this strategy, the United States would back “indigenous and outside forces that desire to overthrow the odious regimes that rule” illiberal states. At the head of this list of regimes was Saddam Hussein’s.

Three years later, as debate broke out over whether to invade Iraq, McCain put himself squarely on the side of Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and the neoconservatives. Like them, McCain evinced a blithe optimism about America’s ability to transform Iraq. Asked by Chris Matthews in March 2003 whether the Iraqis would treat Americans as liberators, McCain replied, “Absolutely, absolutely.” Echoing The Weekly Standard, he also promoted the most alarmist versions of the threat posed by Saddam, insisting that “Saddam Hussein is on a crash course to construct a nuclear weapon” and that “the interaction we know to have occurred between members of Al Qaeda and Saddam’s regime may increasingly take the form of active cooperation to target the United States.” And he indulged wildly optimistic scenarios about how the war might liberalize the Middle East, arguing that “regime change in Iraq” could result in “demand for self-determination” throughout the region.

As the war unfolded, McCain remained a Chalabi booster. With the Iraqi military crumbling in early April, McCain signed a letter with four other Republican senators complaining that Chalabi’s INC was not being funded. Appearing on “Good Morning America,” he argued for “bringing in Chalabi and the Iraqi National Congress as soon as possible.” And, though he would later criticize the Bush administration for giving the public “too rosy a scenario” about postwar Iraq, McCain was, in fact, a major player in this deception. In May, he wrote, “Thanks to a war plan that represented a revolutionary advance in military science, to the magnificent performance of our armed forces, and to the firm resolve of the President, the war in Iraq succeeded beyond the most optimistic expectations.”

For McCain, disillusionment would begin to set in after he traveled to Iraq in August 2003. He returned home convinced that more troops were needed, but, in a meeting with Rumsfeld, his advice was dismissed. The Weekly Standard and McCain began a campaign for more troops--and against Rumsfeld. The arguments echoed what McCain had said decades earlier: that the Vietnam war had been lost because of ineffective civilian leadership. Now he was making the same charge about Iraq.

Yet, even as the administration resisted his call for more troops, McCain continued to insist that the war was being won. After the January 2005 elections, which Sunnis boycotted, McCain said, “I feel wonderful. I feel that the Iraqi people, by going to the polls in the numbers that they did, authenticated what the president said in his inaugural speech: that all people seek freedom and democracy and want to govern themselves.” As late as this July, McCain was assuring viewers of “The Early Show” on CBS that “most of Iraq is pretty well under control.”

In short, McCain’s record on Iraq does not inspire confidence. He was wrong about Chalabi, he was wrong about Iraq’s ties to Al Qaeda and WMD, he was wrong about the reaction of Iraqis to the invasion, and he was wrong about the effects on the wider Muslim world. As McCain prepares to run for president, it’s worth asking: Does he understand that he made mistakes? Does he draw any lessons from these mistakes? And is he once again willing--as he was during the ‘90s, when Srebrenica laid bare the steep price of realism--to adjust his worldview accordingly?

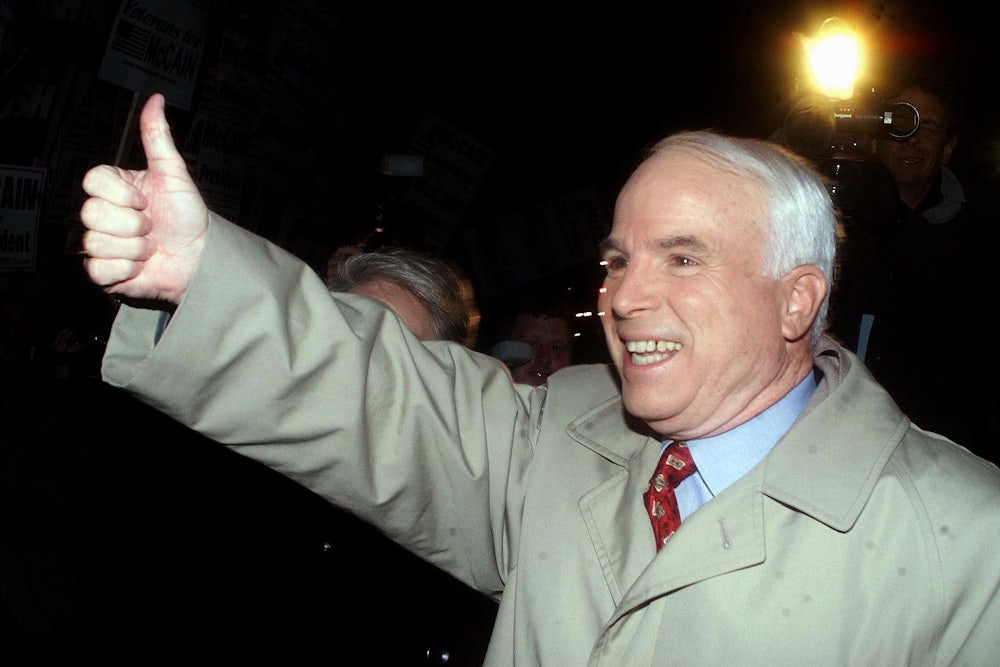

I visited McCain on a hot summer afternoon in Washington and was shown into his office. This time, both his press aides were in attendance and were taking notes. I hadn’t seen McCain in three years and had heard that he had aged significantly, but I thought he appeared to be in good shape. Like white-haired Barbara Bush, McCain, at one point, seemed older than his peers. But now, at age 69, he seems younger. The scar down his face from an operation for melanoma in 2000 is less pronounced than it once was. And he continues to have the best political voice--husky and commanding, without being condescending--since Ronald Reagan.

I asked McCain whether he had taken lessons from the Iraq war similar to the kinds of lessons he drew from Vietnam. He quickly invoked the need for more troops. “The lesson is almost the Powell Doctrine,” he said. “Almost. Every smart person I knew said ... in order to control this country there is almost a formula of the number of troops that are required.”

I told him a story I had heard about the eminent British military historian, Sir Michael Howard. Speaking ten years ago at the Library of Congress, Howard, who had supported the war in Vietnam, was asked whether he still believed that the United States should have intervened. Howard reportedly replied, “It’s a good thing you lost that war. Because if you had won, you’d still be there.” McCain laughed at the story, but brushed aside its point. Instead, he returned to another tactical analogy with Vietnam: “One of the things that bothers me about Vietnam, I mean Iraq, is these grand sweeps that we are doing in urban areas ... instead of clear-and-hold, which [General Creighton] Abrams employed in Vietnam and enjoyed a degree of success.” McCain was saying that, if the United States would employ Abrams’s strategy in Iraq, we might yet achieve the success that has eluded us.

McCain wasn’t willing to concede that there was any flaw in the basic strategy of taking over and attempting to transform an Arab country highly sensitive to Western domination. I told McCain I thought that he failed to appreciate the power of nationalism, either in Vietnam or Iraq. “I hope I have a strong appreciation,” McCain replied. “I think it is fundamental. The Ukraine revolution--they had their revolution to divorce themselves from Russia. I think it was the same thing in Georgia. Nationalism was the first thing that caused the breakup of the Soviet Union. I hope I place sufficient emphasis on nationalism.” But McCain did not address longstanding Arab resistance to Western occupation--whatever the occupier’s expressed motives.

I asked whether he had second thoughts about the case for war that he and the administration had made. I asked about his support of Chalabi in 1998. Hadn’t Zinni been right about Chalabi and the INC? “I never supported Chalabi, per se,” he said. “I supported getting Iraqis to stand up and help in the liberation of their country. Was I too enamored with the INC? I would say yes. I would say yes.” He also conceded that he “underestimated the difficulty of bringing democracy to a people who had been driven to the ground and oppressed in such a brutal fashion.”

McCain has blamed the misinformation that the public received before the war on a “colossal intelligence failure.” But hadn’t Bush officials, I pointed out, exaggerated and distorted what they knew? I read McCain excerpts from Cheney’s March 16, 2003 “Meet the Press” appearance in which he claimed that Saddam “has a long-standing relationship with various terrorist groups, including the Al Qaeda organization” and had “reconstituted nuclear weapons.” Isn’t it true, I asked McCain, that Cheney didn’t know these things, but rather asserted them in the face of considerable evidence to the contrary--for instance, from the International Atomic Energy Agency and the CIA? In response, McCain got a little testy. “I would remind you,” he said, “that every intelligence service in the West shared the same view. That is compelling. When the French believed that, then it has weight. The French, the Germans, and the Israelis believed the same thing.” (In fact, they didn’t share Cheney’s view that Iraq had reconstituted its nuclear program.)

I asked McCain about U.S. policy toward Iran. He had said previously that the only thing “worse than the United States exercising a military option” would be “Iran having nuclear weapons.” This suggested that he favored a preventive strike. Citing Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s statements about Israel, he told me, “We haven’t taken the military option off the table, but we should make it clear that is the very last option, only if we become convinced that they are about to acquire those weapons to use against Israel.” Did that mean, I asked, that Ahmadinejad’s statements about Israel made it unacceptable for Iran to acquire the sheer capability to use nuclear weapons? At this point, McCain seemed to back off. “I think that if they are capable with their repeatedly stated intention, that doesn’t mean I would go to war even then. That means we have to exhaust every possible option. Going to the United Nations, working with our European allies. If we were going to impose sanctions, I would wait and see whether those sanctions were effective or not. I did not mean it as a declaration of war the day they acquired weapons.”

As our hour was drawing to a close, I told McCain that, from what I had learned, he had been very influenced by the neoconservatism of Kristol, Kagan, and The Weekly Standard. “I don’t know whether I fit that label or not,” McCain replied. He added that he also talks to Brent Scowcroft and Henry Kissinger. I asked him whether he had ever had any major disagreements with Kristol, Kagan, or the magazine itself. “I am sure there have been issues that we have disagreed on,” he said, “but I think, generally speaking, I agree with and respect them enormously. I would be glad to go back and look at it.”

I saw McCain once again this fall. I wanted to find out whether he had modified any of his positions, but I could detect little change. I asked him about a statement he had made arguing that Bush couldn’t increase troop strength in Iraq because it would be impossible to “sell that” to Americans. This made me wonder whether McCain had abandoned his own call for more troops. But, during our interview, he said he wanted to “retract” that statement. “If I were president, if I thought that was still necessary, I would risk the presidency, because I would make the case if I thought it was necessary to prevail,” he said. McCain’s insistence on this point suggests that he still hasn’t learned any lessons from our misadventure in Iraq.

That’s too bad, because, if McCain were to reevaluate his positions on the Middle East, he might make a very effective president. He has the ability to lead and a good sense, domestically, of where the country ought to go. Indeed, I talked to several liberals who know McCain and who opposed the Iraq war but who still wouldn’t mind seeing him in the White House. Gary Hart laments McCain’s embrace of the neocons, but still likes the idea of a McCain presidency and was worried that his enthusiasm might “sink his chances.” A former top aide to a leading Democratic presidential contender admitted being ready to pull the lever for McCain in 2008: “I would rather have someone standing up for their point of view than trimming their sails like Hillary [Clinton] or John [Kerry] are. A lot of my friends think that, too.”

Part of McCain’s attraction for me and other opponents of the Iraq war is that his hawkishness would give him the credibility to sell a diplomatic alternative to the imbroglio that Bush has created in the Middle East. Indeed, he is probably the best equipped of all the potential presidential candidates to extricate the United States from the ditch into which it has fallen. But doing so would require him to break substantially with his own recent history.

During our interview, I asked McCain whether he had changed his opinion that the Vietnam war was winnable--a view he had reaffirmed most recently in his memoir, Faith of My Fathers. His response surprised me. “I would say [it was a] noble cause,” he said. “I still believe that. But do I believe it was winnable? I am not sure.” If McCain is willing to reconsider his most basic belief about Vietnam, he could still change his mind about Iraq. It’s true that little he said to me suggests he will adjust his worldview in the near future, but McCain has surprised his critics before. Perhaps he will do so again.