When I see people planning marches and other actions against Trump and his attack on the U.S. government, I am sympathetic. I endorse their revulsion at the president’s disruptive methods and chaotic goals. But I don’t think it is time to march—yet. Big protest marches without follow-up steps could even be counterproductive at this point, because they might simply drain off energy and tensions without leading to anything.

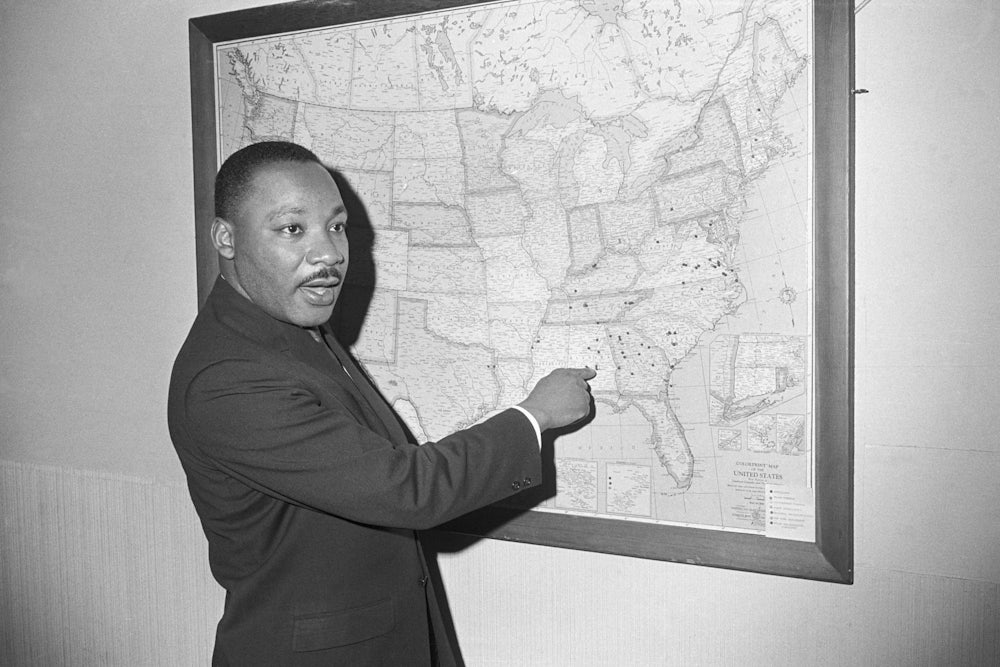

To deal effectively with a major problem, you have to hunker down and ready yourself for a long-term struggle. This was one of the great lessons learned by Martin Luther King Jr. and others in the Civil Rights Movement. There was little that was spontaneous about their movement, and that was a good thing. Preparation for actions was essential. In the Montgomery bus boycott in the mid-1950s, which essentially was a year-long siege of the white power structure of the city, elaborate efforts were made to secure communications, enlist churches, organize carpools to provide alternative transportation, and raise funds to pay for the gas for the cars being used.

By contrast, when the Civil Rights Movement got pulled into an action in Albany, Georgia, in 1961, it was not prepared, had not studied its adversary, and essentially was defeated.

King and his colleagues studied such setbacks and learned. Before going into Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963, they spent months preparing. As he would put it in his letter from that city’s jail that year, “In any nonviolent campaign there are four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self-purification; and direct action.”

Those steps may sound airily Gandhian, but they actually were quite practical as they were applied by the Civil Rights Movement.

First, figure out who you are, and what you want to change, what actions might achieve those goals, and how much you are willing to sacrifice in those actions. This involves a lot of heartfelt conversation and intense listening. For example, before people were permitted to join the 1961 Freedom Rides to desegregate bus stations in the South, they had to write a will and a letter explaining to their parents what they died for. This helped them when they were attacked with rocks, boards, and firebombs by mobs in Anniston, Alabama, and then Birmingham and Montgomery, as police stood by and watched.

Second, consider what tactics you will need to employ. For King, his fellow leaders James Lawson, James Bevel, Diane Nash, and the people around them, this meant studying how to apply the methods of confrontational nonviolence—and also studying the methods of your foes. It took a lot of training for people to learn how to take a blow without either fleeing or responding with violence—and then to show up again the next day for more mistreatment. Fundamentally, it meant changing how people thought about themselves. As one leader taught, “The sheriff is not after you; you are after the sheriff.”

The movement sought conflict in order to make the system of repression show its true face, and then to try to recycle that destructive energy into something positive. For example, in Birmingham, so many marchers were arrested, many of them children, that there was no more room for them in the jails. To deter other marchers, city authorities brought out police dogs and fire hoses, which shocked the nation, including President John F. Kennedy. That reaction finally forced the city to seek a negotiated end to the demonstrations.

Third, figure out what sort of people are needed to carry out such creative, disciplined tactics. Find them and recruit them. Then train them intensely in those tactics, not just talking about them, but acting them out. For example, before the Nashville sit-ins in 1960, students spent hours in church basements rehearsing how they would sit in at lunch counters; how they would react to being hit, spat on, having cigarettes ground out on their backs, or hot coffee poured on them. These exercises not only prepared them for what they would endure but also built bonds of trust and common understanding.

Then go out and do it in direct action. And do it again the next day, each time with focus and discipline. “Keep your eyes on the prize” was not just an inspirational song; it was good strategic advice. Have team leaders enforcing the rules, and monitors on the sidelines watching and taking notes, so they would be able to testify later in court about what they saw, and when events occurred. One of the participants in the Nashville sit-ins, John Lewis, actually typed up and mimeographed 10 basic rules for demonstrators, such as, “Sit straight. Always face the counter.”

The key to these protests was not size but sustainability. For example, rather than have 100,000 people coming and going in a one-day march without any result, it probably would be more effective to have 200 people show up outside the White House or the offices of, say, Senator Chuck Schumer, every day for 500 consecutive days. Chant all day, make it clear that the resistance to Trump runs strong and deep. Don’t blow off pressure. Build it up and set the pace. Make it so the system simply can’t ignore your demands.

Some might ask, what about the 1963 March on Washington that followed the Birmingham campaign? That indeed was a splendid one-day action. But it was not a classic protest. Rather, it was a ceremony of observance and a celebration in which the Civil Rights Movement took the stage in Washington, D.C., in order to introduce itself to the nation. Before then, it had been seen as a regional movement that often went uncovered by the national media. That memorable day in Washington was designed to speak directly to the American people without intermediation by politicians or journalists. It succeeded marvelously. But it was a victory lap, not the beginning of a new series of protests.

And just a few weeks after the March on Washington, the opponents of the movement responded by planting 19 sticks of dynamite in a church in Birmingham, killing or maiming 16 worshippers on a Sunday morning, many of them children. It was a shattering moment that was disorienting for the movement. Dr. King found himself wondering, he later wrote, “If men were this bestial, was it all worth it? Was there any hope?” This may have been the time when all that training and preparation, and the organizational cohesion it produced, proved most essential. In its wake, one of King’s advisers, Diane Nash, wrote a proposal to shut down Montgomery, the capital of Alabama. Even King was skeptical of it, responding, “Oh, Diane, get real.”

Yet Nash’s plan came to fruition early in 1965, with the march from Selma to Montgomery. By then the leaders of the Civil Rights Movement were seasoned veterans. They knew how to run a march, how to maintain security, how to keep an eye out for provocateurs who might use violence to provoke a police reaction. They ran circles around Governor George Wallace. And they shut down his Capitol while he hid inside his office behind a drawn curtain. And they soon had in hand one of the most important laws in American history, the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Arguably, through their actions, they made America a genuine democracy for the first time in its history.

So, I think, slow and steady will prove more effective than fast and unfocused. This is a time to prepare. We should reflect, decide how to act, prepare to act, and put together a resistance to Trump that is strong, sustainable, and relentless.