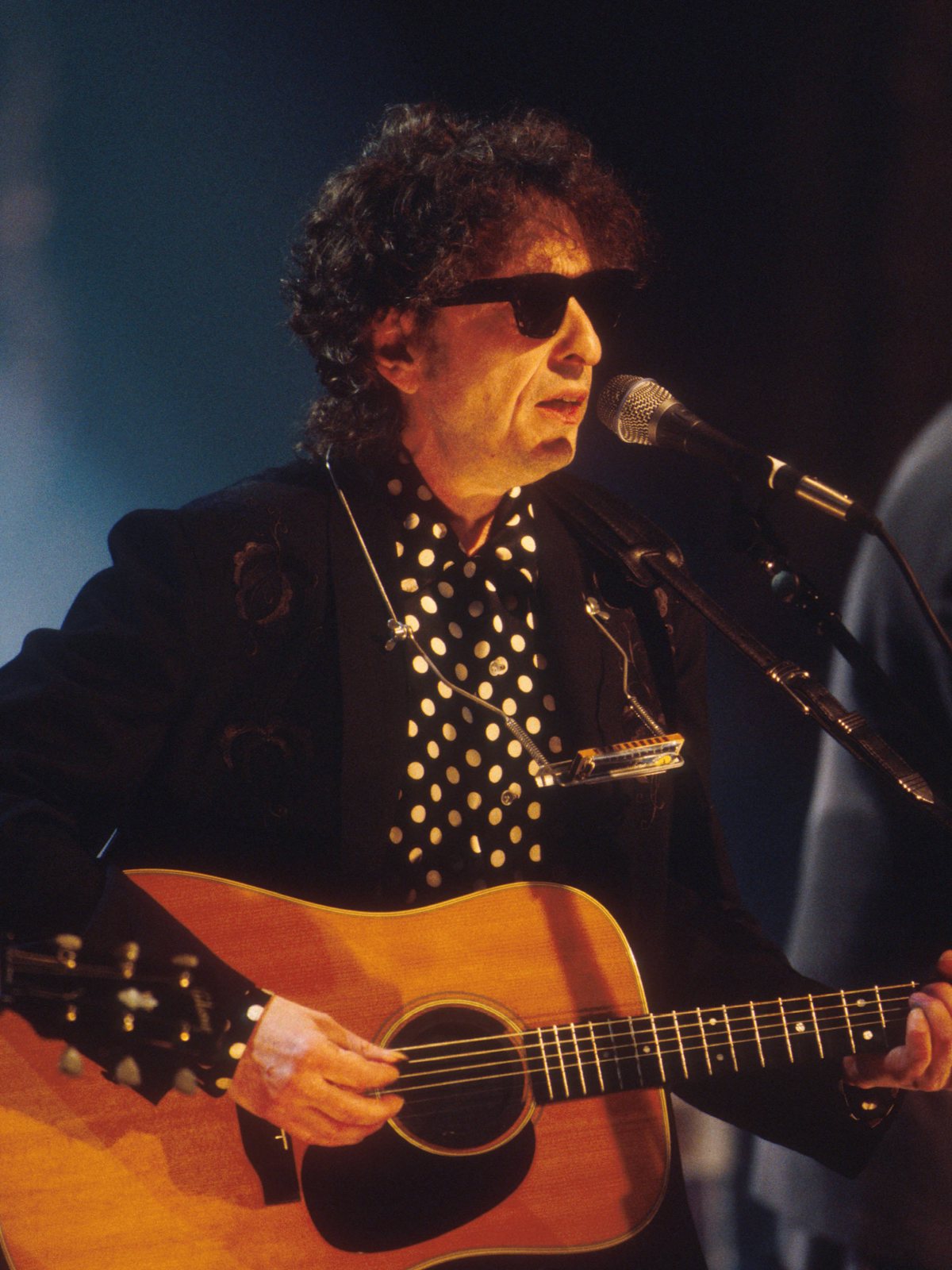

When my fellow classmates and I entered Harvard College in the fall of 1963, our future and the future of our nation seemed bright and full of infinite promise. The charming, handsome, and charismatic John F. Kennedy, a Harvard graduate, was president of the United States. The civil rights movement, which promised at last to give Black people in America equality, was gathering an apparently unstoppable force; the now legendary March on Washington had taken place a month earlier. At that seismic event, a young songwriter and folk singer named Bob Dylan had sung “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” his anthem about the murder of civil rights leader Medgar Evers. (In the recent feature film about Dylan, A Complete Unknown, there is a short news clip showing him in the midst of singing it at that rally.)

Our optimism and good feeling about the future were shattered on November 22 of that year when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated as his motorcade wound its way through Dallas. Evidence shows that this event was also a crucible for the up-and-coming American bard who substituted the first name of the great lyrical poet Dylan Thomas for his real last name, Zimmerman. His 2020 album, Rough and Rowdy Ways (his thirty-ninth of 40 studio recordings), features a biting meditation on the Kennedy assassination, titled “Murder Most Foul.” Some of its lines: “Go down to the crossroads, try to flag a ride/That’s the place where faith, hope, and charity died”; “The day that they killed him, someone said to me, son/The age of the Antichrist has just only begun.”

These words capture the overall bleakness of America’s trajectory since my freshman year in college and Dylan’s emergence as a force in American culture. Back then, we could not have imagined it in our worst nightmares, though it seems perhaps Dylan might have been attuned to the possibility. On election night in 2008, he was giving a concert at the University of Minnesota, where he had spent a freshman year singing Woody Guthrie songs in the coffeehouses of the adjacent bohemian Dinkytown.

After Barack Obama was declared the winner, Dylan appeared on the stage and explained to the audience that he had been born in 1941, the year the United States entered World War II, and had felt himself living in a dark tunnel ever since. This was the first time, he said, that he’d seen a sign of light. But we know now that Obama’s electoral victory was a false flag operation on the part of fate. It was, in fact, a prelude to the possible political disintegration of the nation.

The first Dylan concert I attended was the final show of his 1974 tour with the Band, in Los Angeles. It was the culmination of Dylan’s comeback tour after an eight-year absence following a motorcycle accident in 1966, suffered after his return from a second tour of England, and some of his best-known songs had been drastically rearranged. My second Dylan concert, in downtown Portland, Oregon, in early 1980, was during the unfortunate Gospel Tour. The less said the better about those execrable songs, but, as we know, Dylan did marry his backup singer and produce a child with her (keeping the whole thing secret until after they were divorced). In May 1991, on the lawn of the Charles Ives Center in Danbury, Connecticut, I encountered a very lost and defeated-looking Bob Dylan, who sang one song so badly that I had to go up and stand right next to him to figure out that it was “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” which I knew by heart. Not too much later, however, in October 1992, I attended the thirtieth anniversary concert (the anniversary was of his first album, Bob Dylan, which sold only about 2,500 copies). This concert was magnificent, featuring, among others, the Clancy Brothers singing “When the Ship Comes In” in their deep-throated, sonorous Irish voices, and George Harrison doing a magnificent version of “Absolutely Sweet Marie.” When Dylan himself appeared onstage, however, looking emaciated and sallow, to sing “Girl From the North Country,” you feared that he could collapse at any moment, and you suspected that drugs and perhaps alcohol were getting to best of him at that time (which brought to mind a friend of mine, a heroin addict in his youth, who once told me that on the street there was something called the Dylan Fix, where you mixed together every kind of drug available before shoot-up). In October 1994, I went to a Dylan concert at the Roseland Ballroom in New York City, where, after finishing an extraordinary set, he was joined onstage by Bruce Springsteen and Neil Young to sing, among other songs, “Rainy Day Women # 12 & 35.” At the end of August 2008, while attending a conference in Aspen, Colorado, I purchased tickets for myself and my companion for a Dylan concert at nearby Snowmass Village. We were given a choice, at intermission, between staying on for the rest of the show or going back to our hotel. Dylan’s performance was so bad, so deliberately bad—you couldn’t comprehend a thing he was saying—that practically every single person chose to leave at intermission. One of my last Dylan concerts was at the University of Portland, where Merle Haggard opened by apologizing for writing his song “Okie From Muskogee” (which didn’t stop him from singing the song), and Dylan played on a keyboard so loudly that you couldn’t make out any part of what he was singing.

Apparently over 2,000 books have been written about Bob Dylan, and you can find an impressive number of films out there, including one by Todd Haynes called I’m Not There, in which he is invoked in six different guises. Is it possible to find a real, hardcore Bob Dylan? I will ponder this next time.