The hard lesson of 2024 is that liberals spent too much time fretting that Donald Trump would subvert democracy if he lost and not enough that Trump would win a free and fair election. We can argue about the reason why voters elected Trump—inflation, transgender hysteria, Joe Biden staying too long in the race—but we can’t pretend that those who cast their vote for Trump didn’t know they were choosing oligarchy.

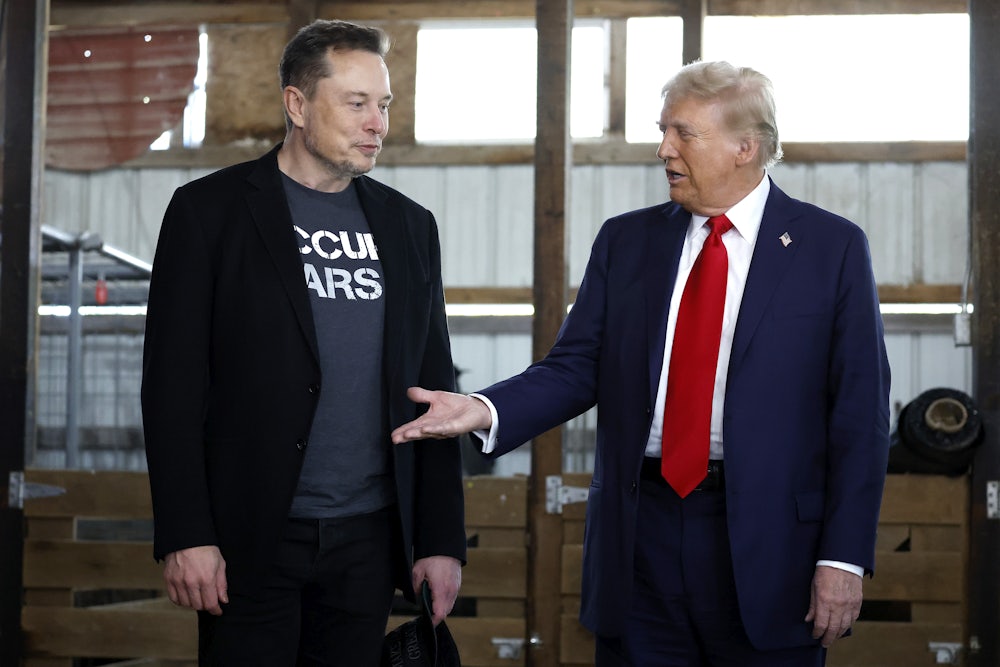

Thanks to the 14-year run of The Apprentice, even the politically ignorant were well aware that Donald Trump (net worth $6.2 billion, per Forbes) was a wealthy real estate tycoon. If anything, the voting public judged Trump wealthier than he really is; as John D. Miller, a marketer for the NBC series, pointed out in October, “We created the narrative that Trump was a super-successful businessman who lived like royalty.” Given that narrative’s predominance, nobody can be surprised that the president-elect’s sidekick ended up being the richest person in the world, or that he’s appointed a dozen billionaires to top posts.

How could this happen? None of liberals’ usual explanations is available. We can’t blame Trump’s victory on the distortions of the Electoral College (as we could in 2016) because Trump won the popular vote. And we can’t blame Trump’s victory on the distortions of money, because even when you figure in outside money, including more than a quarter-billion to Trump from Elon Musk, it was the loser, Kamala Harris, who raised the most cash. Yes, Trump indicated before the election that if he lost he wouldn’t accept the result, just as he still refuses to concede the 2020 election. But in the end, democracy didn’t come under threat. Democracy turned out to be the problem.

This has happened before. The worst presidential choice prior to 2024 was James Buchanan in 1856. Like Trump, Buchanan won both the popular vote and the Electoral College. These two presidents are the lowest-ranked in an annual poll of American political scientists, and Buchanan ranks last in a 2021 survey of American political historians (though for some mysterious reason that one ranks Trump only fourth-worst). Buchanan is reviled for fumbling Confederates’ threats to secede, which of course led to the Civil War. I would argue that the public also chose very badly in reelecting Richard Nixon in 1972 and George W. Bush in 2004—and that in choosing Ronald Reagan in 1980, the party cleared a path that eventually led to Trump.

But 2024 may be the first election in American history in which a majority of United States voters specifically chose oligarchy. This is terra incognita, but it turns out to be a problem to which our second president, John Adams, gave considerable thought.

None of the Founders fretted as much about oligarchy as Adams; he was writing about its dangers as early as 1766, and in 1785 he urged that the Pennsylvania Constitution permit sufficient payment to its legislators to allow ordinary people to serve, lest “an Aristocracy or oligarchy of the rich will be formed.” Six years after he ended his presidency (the weakest part of his legacy), Adams wrote that “the Creed of my whole Life” had been that “No simple Form of Government, can possibly secure Men against the Violences of Power. Simple Monarchy will soon mould itself into Despotism, Aristocracy will soon commence an Oligarchy, and Democracy, will soon degenerate into an Anarchy.”

By this time in his life, Adams had come to believe that the ideal government balanced democracy against elements of monarchy and aristocracy. Adams is widely judged (by the conservative writer Russell Kirk, among others) to have evolved after the American Revolution into a conservative apologist for privilege. There’s plenty of evidence for that view, including Adams’s ridiculous suggestion, as vice president, that President George Washington be addressed as “His Highness, the President of the United States of America, and Protector of the Rights of the Same.” Adams’s successor, Thomas Jefferson, was so appalled by two ornate coaches with silver harnesses that Adams left behind that Jefferson refused to keep them, much as Jimmy Carter would later cut loose the presidential yacht Sequoia, used by every president back to Franklin Roosevelt.

“I think his experience in London, where he was American ambassador during and especially immediately after the war in the 1780s, really shaped his opinion about oligarchy,” Holly Brewer, Burke professor of American history at the University of Maryland, told me. “He became more comfortable with it.” The carriages, pulled by six horses, were “modeled after how the king traveled in London,” Brewer said.

But there’s an alternative view. C. Wright Mills identified Adams as a more incisive critic of the power elite than Thorstein Veblen, and Judith Shklar and John Patrick Diggins voiced similar opinions. In the 2016 book John Adams and the Fear of American Oligarchy, Luke Mayville, a Yale-trained historian and co-founder of the grassroots group Reclaim Idaho, takes this argument further. “In his letters, essays, and treatises,” Mayville writes, “Adams explored in subtle detail what might be called soft oligarchy—the disproportionate power that accrues to wealth on account of widespread sympathy for the rich.” Adams did not judge this attraction benign, but neither did he believe it could be wished away.

The Framers of the Constitution, Mayville argues, believed in checks and balances among various government institutions, but they did not consider any need to balance the power of government against the power of wealthy private citizens. Adams thought otherwise. “The rich, the well-born, and the able,” Adams wrote in A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America (1787–8), “acquire an influence among the people that will soon be too much for simple honesty and plain sense, in a house of representatives.” Adams’s solution to this imbalance of power was to separate out “the most illustrious” among this elite and corral them into the Senate.

Jefferson and other Adams critics saw this as elevating the oligarchs. But Adams judged it “ostracism” because it removed the rich from the sphere of self-interest. A modern expression of this conceit would be that “it takes a thief to catch a thief.” Former Senator Jay Rockefeller was precisely the sort Adams had in mind: knowledgeable and disgusted in equal measure about the tricks by which oligarchs like his great-grandfather John D. Rockefeller acquired and held power. Other former senators in this mold included Herbert Kohl and, to a lesser extent, former Senator John Heinz. But you can’t count on getting a Rockefeller or Kohl or Heinz. Sometimes you get Rick Scott. Jefferson understood this better than Adams. In a letter to Adams, Jefferson argued that “to give [oligarchs] power in order to prevent them from doing mischief, is arming them for it, and increasing instead of remedying the evil.”

The Constitution ended up giving the Senate more power, and the president less power, than Adams thought wise. Jefferson thought the opposite. “You are afraid of the one,” Adams wrote Jefferson, “I, the few.… You are apprehensive of monarchy; I, of aristocracy.” Adams judged a strong president a natural ally of the many against the oligarchs. That theory worked superbly with Franklin D. Roosevelt and reasonably well with John F. Kennedy. It works not at all with Donald Trump.

Adams may have been naïve about the possibility that a rich sociopath like Trump might eventually come to power, but in Mayville’s view, Jefferson was just as naïve to believe that oligarchy would wither and die if government would only deny it power.

Mayville summarizes Jefferson’s view as “Old World aristocracies would be replaced in the republican age by new natural aristocracies of virtue and talent.” To a great extent that eventually happened, aided in the twentieth century first by the spread of publicly funded high schools where attendance was mandatory and, at midcentury, by the spread of higher education.

Mayville summarizes Adams’s very different view as “wealth and family name would continue to overpower virtue and talent.” Half a century ago that judgment would have seemed hopelessly old-fashioned, but it’s a lot harder to dismiss today. Wealth accumulation among the very rich and weaker inheritance taxation at the state and federal levels brought a revival, in the words of the inequality expert Thomas Piketty, of “patrimonial capitalism.” Donald Trump is the consummate patrimonial capitalist, with his real estate success built atop at least $413 million from his father; with his surly, dim-witted older sons managing what’s left of the Trump Organization; and with his more polished daughter Ivanka capitalizing on the family name.

Jefferson failed to anticipate that the voting public would resent his natural aristocracy of virtue and talent—the people we today call meritocrats—much more than trust fund brats and hedge fund billionaires. Indeed, Adams defined “aristocrat” (he also meant “oligarch”) as those who exercise the most electoral sway. “By aristocracy,” he wrote, “I understand all those men who can command, influence, or procure more than an average of votes.”

Why do rich people exert so much influence? Money is the obvious answer, and Adams acknowledged its power. But in The Discourses on Davila (1790) he emphasized another, more psychological explanation. There is, Adams wrote, a universal desire “to be seen, heard, talked of, approved and respected, by the people about [us], and within [our] knowledge.” In short: We all live to show off. This is why Mills compared Adams to Veblen; one might also compare Adams to the journalist Tom Wolfe, the preeminent chronicler of social status in the late twentieth century. Granted, among idealistic college students, associating oneself with the wretched of the earth yields greater status, but for most of the rest of us associating oneself with the rich is what gets the job done. Adams again (in The Discourses on Davila, quoted by Mayville):

Riches force the opinion on a man that he is the object of the congratulations of others, and he feels that they attract the complaisance of the public. His senses all inform him, that his neighbors have a natural disposition to harmonize with all those pleasing emotions and agreeable sensations which the elegant accommodations around him are supposed to excite.…

As Trump put it in the Access Hollywood tape: “Grab ’em by the pussy. You can do anything.” Sticklers might say Trump was talking about being a TV star, not about being rich. But the specific nature of Trump’s stardom was that he played an exaggerated version of himself on TV: A very rich man who, because he is very rich, can get away with anything. During his first presidential term, Trump showed that he could transgress beyond our wildest dreams—flout the woke hall monitors, lie with abandon, defy the law—and get away with it all because he was rich. Even the many Trump voters who pulled the lever for him in 2024 while disapproving of his personal behavior tend to envy the man.

Trump Envy isn’t the only political force out there; that explains why he lost in 2020. But it’s turned out to be shockingly powerful. The United States grew more oligarchical over the past half-century, with the rich accumulating ever-greater power over politics. But Trump represents a quantum leap—supercharged oligarchy not in spite of the public will but because of it. Which makes ours a John Adams sort of moment. This was as bleak an electoral outcome as the country has ever seen, and democracy wasn’t the victim. It was the cause.