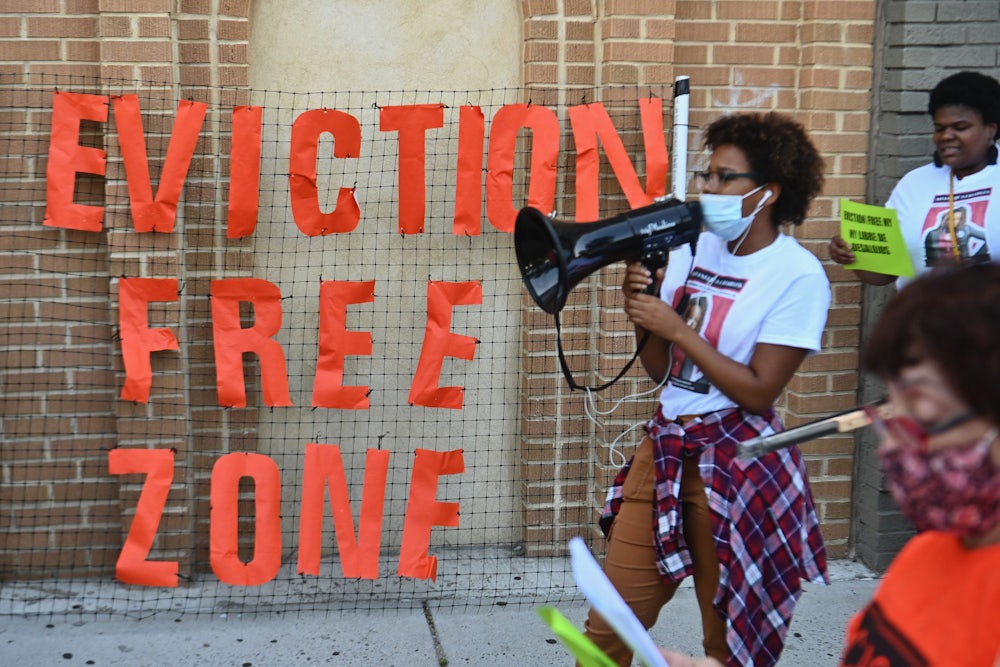

For a fleeting moment in the pandemic, it was common sense that tenants shouldn’t have to pay rent. How could they pay, amid a world-rending health crisis prompting millions of layoffs, when one might have to choose between shelter, debt payments, or groceries? The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s eviction moratorium helped for a time. But landlords found loopholes that allowed them to evict despite the virus, and in August 2021 the Supreme Court killed the mandate off entirely. Housing cases piled up once again.

Today, evictions far exceed pre-pandemic levels, as rents have increased and politicians’ will to help tenants has evaporated. In red states like Texas, save for a few cities, evictions never really stopped, and in 2023 lawmakers took action to prevent local eviction moratoria from ever happening again. In some regions, eviction rates have doubled after natural disasters, exactly when tenants are most vulnerable; experts watching the aftermath of Hurricanes Helene and Milton on the Southeast are already anticipating the spike (in Florida, landlords are under no obligation to waive or even pause rent after a storm). In New York City, where tenants had recently won a right to an attorney, judges facing a dramatic backlog of cases simply scheduled eviction hearings faster than tenants could find lawyers.

On average, the trial to determine if you can remain housed lasts less than two minutes—your fate decided about as quickly as you can watch a couple of TikToks—and a great deal depends on the individual whims of each judge. An eviction can also prevent you from finding housing again: While the Department of Justice cracks down on software firms like RealPage, which allows property owners to collude on rent increases through an algorithm, landlords in many states also routinely scrape housing court data to pinpoint “problem” tenants, effectively blacklisting people as soon as they apply. This partly explains why evictions are associated with high mortality rates: Once the sheriffs force you out of your home, your ability to sit, lie, or camp in public space—the only space immediately available to you—often comes with heavy fines or violent restrictions by police. In some municipalities, it’s illegal for passersby to offer you food without a proper permit. By that point, you are more likely to be arrested than to find an affordable home.

This pipeline to lifelong housing insecurity, which exists with varying degrees of barbarity across the country, is often called the “housing crisis.” In this framing, the central problem is merely a shortage of housing, meaning high demand for a limited supply, driving prices up and making affordable units ever more scarce. The proposed solution is more construction, on the theory that more housing (even the luxury condos that typically get built) decreases demand on cheaper units. But as Tracy Rosenthal and Leonardo Vilchis point out in their new book, Abolish Rent, this approach ignores many of the issues tenants face. “Housing isn’t in crisis, tenants are.” While there is indeed a shortage of cheap units, the housing system is working exactly as designed: It maximizes the profits of landlords, developers, and real estate speculators at the expense of people who need homes. Current efforts to increase construction “do not produce lower rents, but rather rents that rise less quickly,” effectively kicking the can down the road. The “housing crisis” framing also obfuscates the power imbalance between landlords and tenants, and suggests that to “solve” the crisis, we should focus on building more, rather than on giving tenants a voice in their homes.

The argument of Abolish Rent is that the tenant crisis isn’t strictly about “housing units” or land-use codes; it’s about power. “Tenants can’t afford to be passive objects of social intervention or beneficiaries of a quick ‘one-weird-wonky-policy’ fix,” the authors write. Drawing on around a decade of experience organizing the Los Angeles Tenants Union, currently the largest union of its kind in the U.S., Rosenthal and Vilchis demonstrate how tenants can save themselves by flipping the logic of evictions on its head. What if every housing complex was as fit for a union as any factory floor, with bosses that could be confronted, obstructed, and overcome through tenants’ collective strength? What if, together, we refused to pay rent?

Isabel Garcia could name every past owner of her building for nearly 60 years. She moved from Mexico to Boyle Heights, Los Angeles, in 1962. In 2010, a new landlord bought her unit and those of several other tenants and began a campaign of harassment. Garcia’s apartment was protected by a local rent stabilization ordinance, but that didn’t stop her landlord from trying to evict by other means. Rosenthal and Vilchis recount how he installed surveillance cameras and removed the building’s amenities (washing machines, clotheslines, and common spaces), filed repeated “cure or quit” notices, which threaten tenants to “fix” a lease violation in three days or face eviction, and targeted Garcia’s son, who passed the time outdoors, with nuisance complaints. Rather than abandon their homes, she and her neighbors stayed put. The harassment drew Garcia “closer to her neighbors than ever before,” and in 2020, at the start of the pandemic, she decided to withhold half of her rent in solidarity with those who could no longer afford to pay at all.

The rent strike, Rosenthal and Vilchis argue, works on several levels. On the first night of withholding rent, the authors note, tenants are often shocked that nothing really happens: The building doesn’t crumble around them, their keys still open the door, the police don’t come crashing through the windows. While risky (this strategy of attrition can last years, they acknowledge, and “victory isn’t guaranteed”), it also exposes landlords’ overarching dependence on tenants. Just as a labor strike hampers the owner’s ability to profit off the production or distribution of goods, the rent strike tamps the landlord’s source of income, creating leverage from which tenants have won “rent cancellations, rent reductions, direct payments, structural repairs, the restoration of amenities, and more.” Tenants rarely have a say in the condition of their home and cannot predict sometimes steep rises in rent from year to year; people forgo food and medications, exhaust themselves by picking up extra shifts at work, or secure payday loans at extortionate interest to make rent. Even if tenants do everything right, landlords can unilaterally decide they want a different tenant by refusing to renew the lease, thrusting tenants back into the churn of the housing market. But rent strikes claw stability back. “We fight,” Garcia tells the authors, “because we have to continue living.”

The tactic goes back over a century, when thousands of Jewish immigrants living in New York’s Lower East Side tenements withheld rent from slumlords and secured the country’s first housing regulations and rent controls. As a “simple, purposeful inaction,” the rent strike suggests that “the right to housing already exists; all we need to do is claim it.” That purposeful inaction also serves as a shared experience among tenants; it requires coordination, trust, collective decision-making, and community support. “Rent strikes are a means and guide toward the ends of our work,” write Rosenthal and Vilchis. They create an “internal culture of tenant democracy,” connecting residents through a “stronger sense of ownership” over shared space.

The authors follow tenant associations as they begin to reclaim the neighborhood through acts big and small—potlucks, bake sales, art-making, movie nights, even filling in potholes and cleaning up alleyways. In the garden Isabel Garcia had planted outside her building as a teenager, tenants began to host meetings and distributed fresh groceries weekly. (In response, her landlord installed a fence and planted cacti to prevent gatherings.)

YIMBYs imagine that community sprouts out of dense living spaces—that development precedes and enables tight-knit neighborhoods. But density doesn’t guarantee a healthier body politic; studies show that, in cities with increased multifamily construction, some residents actually report feeling isolated and bemoan the loss of community. The goal of the real estate industry is to sell homes, to extract rent, not to build or nurture a social fabric. “Our landlords want to limit our gardens, our yards, even our lobbies to mere amenities,” the authors contend. Indeed, before organizing a rent strike together, they note, many residents of the same apartment complex hardly knew their neighbors. When evictions are experienced alone, they exploit a system that encourages isolation, tricking tenants into feeling powerless to stop them. By contrast, withholding rent together empowers a collective response. Defending your community may also be precisely what builds it.

In a recent review of Abolish Rent, Holden Taylor, a Brooklyn-based tenant organizer, argues in part that Rosenthal and Vilchis’s emphasis on rent gives the impression this is the main “reason that some tenants are houseless while others are (precariously) housed.” If we focus too closely on the price of rent, Taylor writes, we may overlook the precarity of tenants and the many other abuses that owners can inflict on them—“akin perhaps to a trade union fixation on increasing wages” rather than fighting for deeper forms of self-determination.

The book doesn’t fully answer these questions, although it admirably extends the definition of tenant to “anyone who doesn’t control their own housing,” and looks closely at the lives of tenants who have been pushed out of their homes and live on the streets. (More recently, Rosenthal also argued in The New Republic that the Gaza encampments on university campuses signal a shared fight with tenants and the unhoused.) “The tenant struggle is a land struggle,” the book argues. “It is a struggle for collective sovereignty over the use of our resources and the places we inhabit.” In this way, tenant unionism is not dissimilar from the ongoing Stop Cop City protests in Atlanta, or the Landless Workers Movement in Brazil, organized by rural residents who occupied and expropriated vacant estates to form workers’ cooperatives. The point is to prioritize the common good over the corporations and institutions that seek to extract as much profit as possible out of the things we need to survive.

“The actions of tenants already in struggle insist that the solution to our current crisis will not arrive just by building new, publicly owned buildings, but by building power to take back and control public space and the private housing we live in now,” they write. One might look to the squatters’ movement of the 1960s and ’70s, when tenants laid claim to abandoned housing. Some of these homes became cooperatives, while other neighborhoods formed community land trusts to prevent real estate speculation. Such efforts were imperfect, vulnerable to the market in the former case and to funding disputes in the latter. Rosenthal and Vilchis leave the solutions somewhat open-ended, aside from proposing “collective control,” enacting the principle of “small-d democracy,” even “small-c communism” over the places we live. Rather than solely demand new social housing, they argue, we must socialize housing. If this is beginning to sound somewhat vague, that’s because it is, but Abolish Rent doesn’t presume to have every answer. “In our nascent movement, our actions are experimental and provisional,” they write. They organize around the idea of refusing the profit-driven housing model, and propose we learn together, through ongoing collective work, what another world might look like.

Such experimental action may produce still more tactics, the rent strike being one of a set of tools for the tenant movement. While reading, I kept thinking of the suburbs, where single-family homes are the norm and built-to-rent single-family communities are increasingly constructed in high-eviction cities across the Sunbelt, the fastest-growing region in the U.S. “Today,” the authors note early on, “the majority of America’s poor call the suburbs home,” but they never quite return to this fact, which marks the terrain for tenants across the country.

The rent strike has historically worked best in apartment buildings where tenants live close together—with precisely the kind of closeness that suburbs are designed to avoid. Multiple tenants striking at the same time are harder to suppress, but one tenant in a single-unit building? They’re easier to remove. In Houston, my hometown, landlords bought up single-family homes and converted them into rental properties, occasionally dicing them up into multifamily homes, but not always. Some of the zip codes where this practice is common are also eviction hot spots. Which tactics might work here? Abolish Rent is refreshingly confident, the authoritative work on tenant unionism in the U.S. today. But one day, with any luck, it’ll only be the prologue.