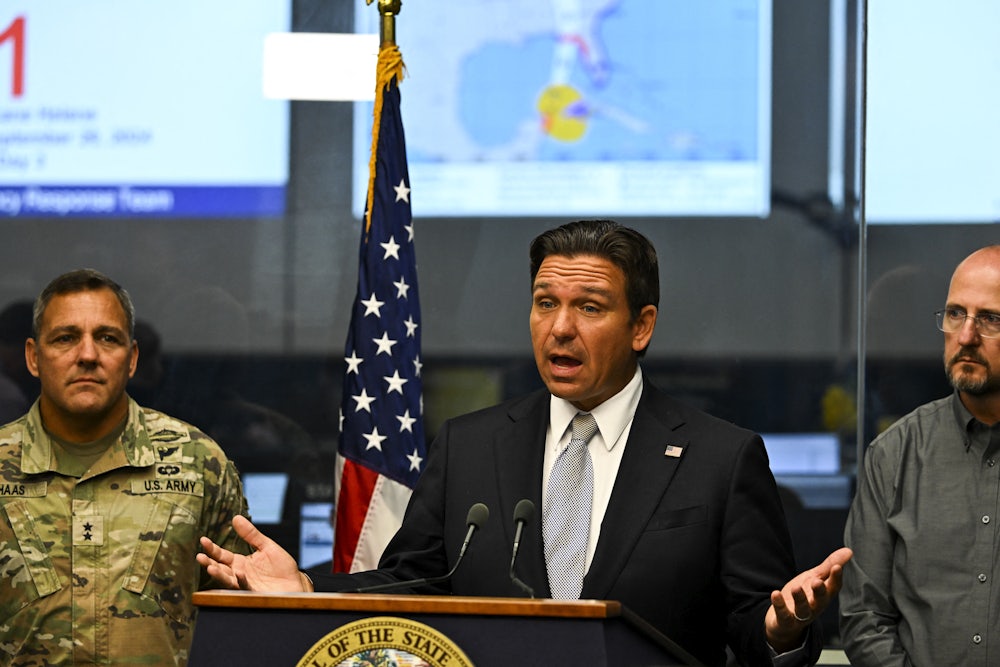

After Hurricane Helene hit in late September, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis visited the town of Suwanee to help serve barbecue to residents. The governor prayed that Florida be spared from another storm that was “brewing” out in the Gulf—a storm now known as Hurricane Milton, which made landfall in Florida overnight. But while handing out plates to people in need, DeSantis also asked them “for help with Amendment 4.” He wanted them to help him block this November ballot measure that could restore abortion rights in the state. DeSantis has apparently refused to allow even hurricane relief to get in the way of his other political efforts.

Amendment 4 gives Floridians the opportunity to reject the near-total abortion ban DeSantis signed following the Dobbs decision. DeSantis has chosen to fight this ballot measure by interfering with the fight: In the weeks leading up to the election, marshaling state agencies in service of defeating the abortion rights ballot measure, DeSantis has spread health misinformation, threatened news organizations, and attempted to intimidate voters. This is, sadly, not unusual for DeSantis. Whether on abortion or other concerns, the Florida governor has turned time and again to undermining the democratic process, to attack the very tools that the state’s residents have to check his power and to protect themselves.

It’s not necessarily out of bounds for an elected official to take a stand on a ballot measure. But when DeSantis uses his X account to repeat the misinformation spread by the measure’s opponents, there’s more going on. “Amendment 4 is a Trojan horse that mandates abortion until birth for virtually any reason—if it passes, taxpayers may be forced to fund it,” DeSantis posted on October 1. “Vote No on Amendment 4 to stop taxpayer-funded abortion-on-demand.” This isn’t true: The ballot measure does not permit abortion after presumed fetal viability (with exceptions for the health of the patient), and it makes no provisions for funding abortion. (These kinds of restrictions are actually controversial in the abortion rights movement, with a growing number of advocates now opposing viability limits, while many in the movement have long opposed bans on public funding for abortion. Nevertheless, the ballot measure does not do what DeSantis claimed it might.)

DeSantis’s claims on X are mirrored and expanded on the website of the state’s Agency for Health Care Administration, or AHCA. “We must keep Florida from becoming an abortion tourism destination state,” the Health Department website urges its audience. This is the agency responsible for administering the state’s Medicaid program, the licensing of health facilities, and sharing health care data. One section representing itself as a fact sheet is headed “Florida is Protecting Life,” and “Don’t Let the Fearmongers Lie to You”—the kind of language one might expect from a political campaign but not a state health agency. The agency’s secretary, Jason Weida, a DeSantis appointee, recently spoke at a campaign event opposing Amendment 4. “Everything that is put out is factual. It is not electioneering,” DeSantis said at another press event, defending the website. “I am glad they are doing it.”

When the AHCA site was launched, about 60 days before the election, Florida Democrats pushed back. “This is completely anti-democratic behavior,” Democratic state Representative Ashley Gantt told the Florida Phoenix; when people talk about The Handmaid’s Tale and “dystopian” societies, she added, “this is how it starts.” Florida law states that “no officer or employee of the state … shall use his or her official authority or influence for the purpose of interfering with an election or a nomination of office or coercing or influencing another person’s vote or affecting the result thereof.” To use “state agency resources for campaign purposes is illegal,” wrote Florida Democratic Party Chair Nikki Fried in a statement, “and we’re looking into any and all recourses to take this website down.”

That was early in September, not long before mail-in ballots would begin arriving at voters’ homes. The ACLU of Florida and Southern Legal Counsel filed a joint lawsuit on behalf of the ballot measure sponsor, Floridians Protecting Freedom, “to prevent AHCA from abusing its power and violating Florida’s Constitution to interfere in the upcoming election,” seeking a temporary injunction. “The State cannot justify its current abortion ban and its dire impacts on Florida’s voters, so instead it is attempting to undermine the political power of the people enshrined in Florida’s Constitution,” said ACLU of Florida staff attorney Michelle Morton. A Florida circuit court judge ruled in favor of the health agency on October 1, allowing the website and ads to stay online.

From there, DeSantis’s administration attempted to flip the narrative. After the ballot measure campaign brought legal action against the AHCA for its misinformation website, the Department of Health’s general counsel threatened Florida’s broadcast television with criminal penalties for allegedly sharing misinformation—by airing a “Yes on 4” ad, made by Floridians Protecting Freedom. In a series of cease-and-desist letters, first reported by investigative reporter Jason Garcia, the state alleged that the ad is “not only false; it is dangerous.” It threatened the station with a “nuisance” law, meant to help the Department to Health address a legitimate threat to health, which it said allowed it to pursue legal action, including an injunction, if the station did not stop airing the ad. “While your company enjoys the right to broadcast political advertisements under the First Amendment,” the letter concludes, “that right does not include free [rein] to disseminate false advertisements, which, if believed, would likely have a detrimental effect on the lives and health of pregnant women in Florida.” The argument, insofar as there is one, involves contesting the story told in the ad by a mother with a terminal cancer diagnosis, who decided to have an abortion so she could undergo cancer treatment, and who in the ad says, “Florida has banned abortion even in cases like mine.” DeSantis and the Amendment 4 opponents keep claiming there are exceptions in the ban that would apply in such cases, but in practice, such exceptions are often nearly impossible to obtain, and not in time to save a pregnant person’s life.

This leaves the DeSantis administration with no real facts to fight. So they are essentially fighting the voters instead. “Florida’s government fears the will of the People, coming after our freedom of speech and engaging in voter intimidation,” Lauren Brenzel, campaign director for Yes on 4, said in a statement, adding that this intimidation tactic comes on top of “launching a state-sponsored and taxpayer-funded political ad—disguised as a website.” In a letter provided to me by the Yes on 4 campaign’s legal counsel, addressed to WCJB-TV, they say the Department of Health letter “reflects an unconstitutional attempt to coerce the station into censoring protected speech.” It goes on to say that they are sure the station has received baseless cease-and-desist letters before, but that in this case, the Department of Health “is threatening the station with criminal prosecution if it does not cease running the Advertisement.” So far, the ads are still running; I caught one Tuesday evening during a Milton advisory on a Tampa station. Likely, they won’t be going anywhere: “The right of broadcasters to speak freely is rooted in the First Amendment,” said Democratic chair of the Federal Communications Commission Jessica Rosenworcel in a statement Tuesday. “Threats against broadcast stations for airing content that conflicts with the government’s views are dangerous and undermine the fundamental principle of free speech.”

“Unfortunately, the tactics we’re seeing in opposition to Amendment 4 in Florida are a continuation of a reprehensible pattern we’ve seen from elected officials in states around the country who are also anti-abortion extremists,” Kelly Hall, executive director of the Fairness Project, a group supporting ballot measure campaigns including Florida’s Amendment 4, told me this week. In Ohio, in Missouri, there were attempts by elected officials to prevent their abortion rights ballot measures from making it in front of voters. Those failed. “Rather than fulfilling their constitutional roles to be stewards of a ballot measure process in which voters get to decide issues of fundamental rights for themselves,” Hall told me, “anti-abortion politicians abuse their power to try to impose their own beliefs on the entire state.”

But this isn’t the only way that the state government under DeSantis is attempting to suppress the democratic process. The Florida Department of State scrutinized tens of thousands of voters’ signatures on petitions used to get the measure on the ballot, claiming to be “concerned” about allegations of fraud, the Tampa Bay Times revealed last month. Then came DeSantis’s “election police” force. Some voters who signed the petitions reported that they were questioned by state police officers on their doorsteps. “What troubled me was he had a folder on me containing my personal information—about ten pages,” one of the voters wrote on Facebook shortly after a detective left his home. It included a copy of his driver’s license and a copy of the petition he signed, he wrote. “Troubling that so much resources were devoted to this.”

The state had already approved the signatures; the deadline to challenge signatures had passed. What was the point of these visits, if not to alert voters that police were watching them? “They want people to stay home and to not vote,” said Democratic state Representative Fentrice Driskell. “They want people to read these articles and hear it on social media that the police showed up at somebody’s door and intimidated them and made them feel bad about signing an Amendment 4 petition.” Defending the election police, DeSantis said, “They’re doing what they’re supposed to do. They’re following the law, and they’re ensuring that anyone that broke the law is going to be held accountable.”

DeSantis first used his election police force in 2022, targeting voters who were formerly incarcerated for felony convictions. In those stings, officers arrived at the voters’ homes, and their arrests, captured on police body cameras, were announced by DeSantis at a campaign event. The stunt capitalized on real uncertainty about the status of voters who had been disenfranchised due to their felony convictions. In 2018, Floridians voted to restore the voting rights of more than one million people who had served their sentences, through a ballot measure also called Amendment 4. In that same election, DeSantis narrowly won, and once in office, quickly worked to roll back those rights, limiting them to only those people who had completed their sentences and paid back often onerous fees and other financial obligations connected with their offense. All the confusion may have kept hundreds of thousands of people who were eligible from registering to vote, a ProPublica–Tampa Bay Times–Miami Herald investigation found in 2020. The weakening of Amendment 4 “may constitute the biggest single instance of voter disenfranchisement,” the investigation found, adding, “Like the poll taxes of the Jim Crow era, the restrictions have especially hit Black Floridians, who make up a disproportionate share of felons and register overwhelmingly as Democrats.”

The 20 people arrested by the DeSantis election police in 2022 had been disqualified from having their voting rights restored. An investigation by The Appeal later found that at least 12 of the 20 people arrested had in fact been sent voter registration cards by their respective counties, “but weren’t pulled from the voter rolls until at least a year later—well after they’d cast ballots.” They learned they had voted in violation of the law only when the election police arrested them in 2022; some of the voters said that before their arrests, they had been assured by state officials that they were eligible to vote. The people punished for multiple layers of confusion and systems failure were the voters.

The arrests of voters with felony convictions served to intimidate voters, to keep people from the polls. DeSantis’s recent work against abortion rights is in keeping with this earlier pattern: The governor is willing to use the power he has to misinform voters and deter them from showing up on Election Day. Meanwhile, abortion and voting rights organizations remain determined to fight. “The tactics we’re seeing in Florida right now are more extreme examples in a long list of extreme examples,” Kelly Hall from the Fairness Project told me. “But Ohio voters saw through these attempts to confuse them, and so will Florida voters.”