When Hector was around three years old, and his brother was just a baby, their parents decided to take the children north, from the little town in Durango, Mexico, where they lived, to the United States. They crossed the border through the unforgiving desert, and ended up in Tucson, Arizona. The boys’ mother put in long hours as a chef; their father worked for a company that made water fountains and concrete benches. To all intents and purposes, the children grew up American.

More than three decades later, Hector—who told me that he has never once returned to Mexico, and whose entire family (his wife and their four children, who are U.S. citizens) and business as a personal trainer are Tucson-based—still lacks paperwork. Like millions of others, he is trapped within the shameful dysfunction, and congressional stalemate, that pass for U.S. immigration policy.

Years ago, the young man had status under DACA, which provided a degree of protection from deportation, along with the right to work, for undocumented immigrants who had been brought into the United States as children. But a minor drug charge, for solicitation to possess marijuana, brought him to the attention of immigration officials. In early 2019, shortly after his two years’ probation was up, armed Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents stopped him while he was driving with his children. The agency brought him to a federally run immigration detention facility in Florence, Arizona, and two weeks later sent him to a privately operated facility at Eloy, where, he said, he remained, in squalid conditions, for nearly three months.

Eventually, Hector’s wife managed to get him released on bond. But his legal woes worsened. At a critical hearing about whether Hector should be deported, his attorney, Margo Cowan, sent to represent him a volunteer lawyer he had never met or spoken with before. That lawyer knew nothing about his case, and showed up only 10 minutes before the hearing was set to begin. Not surprisingly, the judge ruled that Hector should be deported—though no date was set for his removal from the country, and he remains in Tucson as of this writing. Cowan’s team filed an appeal. But then Hector received several letters from the courts saying that required information for his file was missing. The appeals, in consequence, went nowhere. “I trusted her,” Hector, a heavily tattooed, squat man, said of Cowan. “But she wasn’t there for me.”

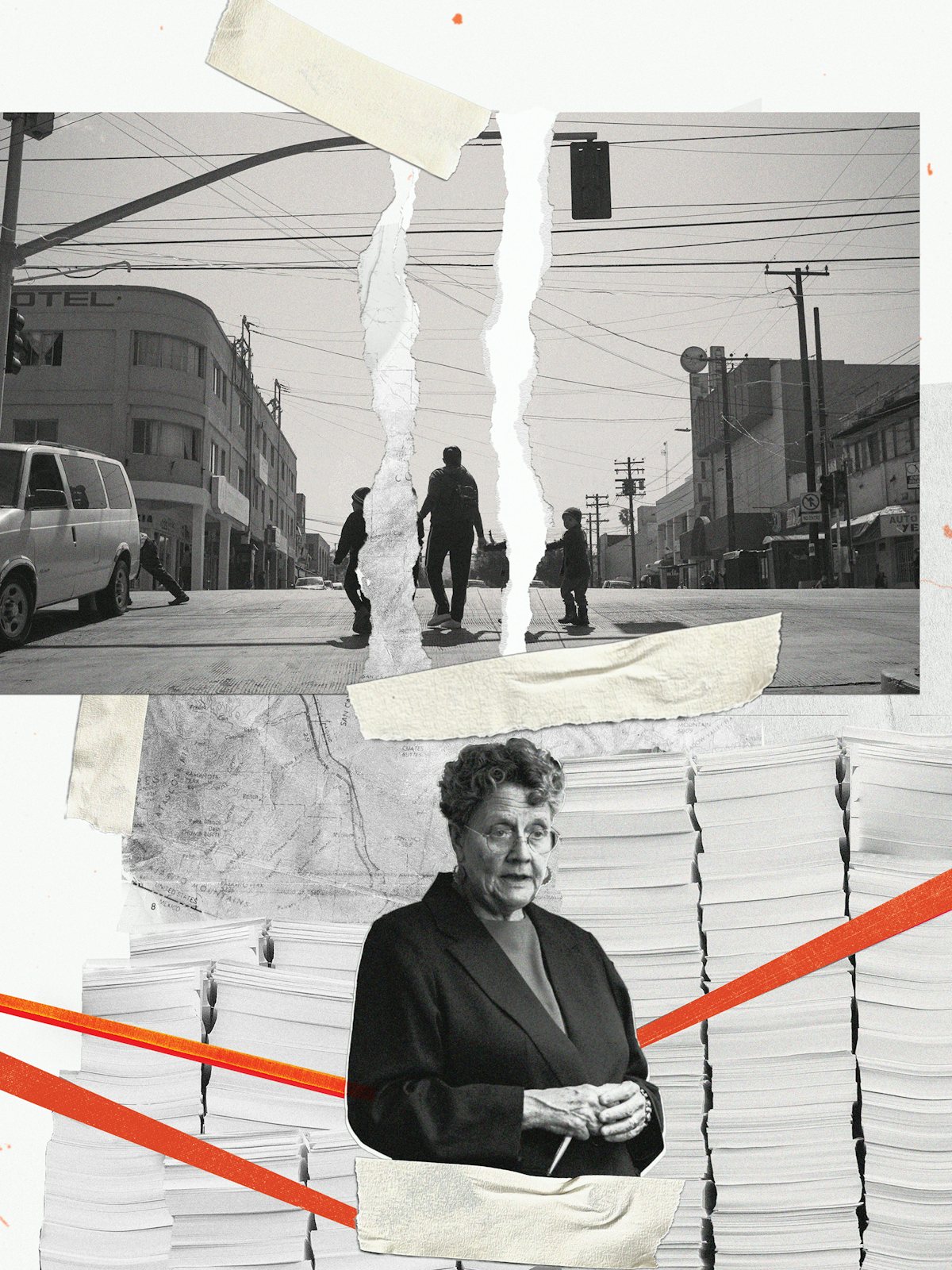

Cowan’s paid job was as a public defender. After hours, on weekends, whenever she wasn’t defending those charged with criminal offenses, she put her heart and soul into working gratis with Tucson’s undocumented immigrant community. Fluent in Spanish, she ran a locally famous volunteer organization called Keep Tucson Together, or KTT, out of a small, blue, adobe bungalow on a residential street, and offered free legal advice at a Thursday evening clinic at Pueblo High School, a huge, redbrick campus on the largely Hispanic south side of town. Cowan had been fighting the good fight for more than half a century, was lionized by progressives in Tucson, and thought of herself as an indispensable part of Tucson’s radical fabric. Her work was, to say the least, challenging; as the federal government sought to deter undocumented immigration by channeling would-be migrants into particularly lethal areas of the desert, increasing numbers of them ended up in those desert wildernesses. The strategy, implemented from the mid-1990s on, was a fiasco: It did not succeed in tamping down migration but did lead to hundreds of thousands of migrants trying to cross into remote parts of Arizona each year, and it has resulted in upward of 20,000 of these men and women being processed through the Tucson immigration courts annually.

For many of them, Cowan’s willingness over the years to work for free was a godsend, a true gesture of kindness in an otherwise bleak environment. Yet as the crisis accelerated, it appeared that Cowan, and the small roster of volunteer attorneys who would step in every so often to do pro bono work for the organization, were bungling some of their cases. Something was going on at Keep Tucson Together. But what was it?

Eventually, with the threat of deportation and permanent separation from his family hanging over him, Hector and his wife decided to raid what little savings they had and pay for a private attorney to represent him. He ended up with the firm of Green Evans-Schroeder, an outfit specializing in immigration law that had taken on scores of Cowan’s disgruntled ex-clients and helped file bar complaints against Cowan in roughly 15 of these cases. (Cowan, for her part, dislikes immigration attorneys who, she says, “extort money” from their clients by “selling knowledge” that should be shared.) His new attorney is now working to remedy the errors made by the Keep Tucson Together team. Hector hopes it isn’t too late. “I don’t know nothing about Mexico,” the 33-year-old told me. Then, incongruously, the tough guy with the fighter’s crooked nose started to cry. “I don’t want to leave my family. I don’t want to leave everything I’ve built since I was little.”

Monica Silva Valenzuela faced a similar crisis. A middle-aged woman, who kept her long gray hair tied back in a ponytail, she had arrived in Tucson from Mexico in 2017, with her son, Jose Angel, then aged 21, and three more of her children, after Jose Angel had been set on fire with gasoline and horribly injured by cartel members in Magdalena de Kino, in the Mexican state of Sonora.

The immigration authorities immediately took Jose Angel to a hospital, where over the following weeks doctors treated the third-degree burns that snaked up his tattooed arms and his back. Not knowing where to turn for help with the family’s immigration case, Monica ended up seeking advice from Margo Cowan and her small team of volunteers.

It should have been pretty straightforward; there was, after all, abundant medical documentation of Jose Angel’s treatment, and the family, which had repeatedly been targeted by the cartels, were prime candidates to qualify for asylum under the provisions of the Convention Against Torture. Instead, Monica alleges, the volunteers at Keep Tucson Together lost her documents and failed to submit required paperwork by the deadlines the courts had set. Finally, Monica received a notification informing her that she now had a removal order against her. “The judge asked them what was the evidence I had to defend my case, and they never submitted the evidence,” Monica told me, sitting in an airy conference room in Jesse Evans-Schroeder’s art-filled offices. “Things about my nephew who had been disappeared, newspaper articles.”

Monica alleged that she provided Cowan’s team with her family’s original documents, including her children’s birth certificates, and that all of those documents subsequently went missing. “I never got anything back,” she said angrily. When she insisted on a meeting with Cowan, the attorney would say words to the effect of, “Yes, I am going to help you, this is a very easy case.” But she didn’t. And when they lost, Cowan promised to appeal—but Monica said the paperwork for the appeal was never filed, and one of the volunteers later admitted to her that he had forgotten to do so. Cowan disputes such claims, arguing that paperwork was always returned promptly, and insisting that the KTT offices have a first-rate methodology for filing the documents entrusted to its care.

Eventually, Monica decided to get another attorney and filed a bar complaint against Cowan, alleging inadequate counsel. As of this writing, Monica remains undocumented but is protected from removal because she has a pending asylum application (filed by Jesse Evans-Schroeder’s team); she also has an extension on her work permit that is valid while the application is being processed.

Usually, scandals about immigration attorneys involve scam artists taking the money of vulnerable and desperate clients and essentially failing to follow through on the outlandish promises they make. The grifters peddle dreams to the poor and walk away with what little money those folks can cobble together. A few years ago, a husband-and-wife team of attorneys in Tucson were sentenced to months in jail and lost their attorney’s licenses for similar practices. By any reasonable measure, Cowan isn’t a scam artist. In fact, from the 1970s, when she served as the youthful director of the immigrants’ rights group Manzo Area Council in Tucson, she has spent her adult life working, for either low pay or no pay, with marginalized people, and her efforts to secure publicly funded representation for anybody in need who has a case in immigration court have been backed by U.S. Representative Raúl Grijalva and have received financial donations from luminaries such as Lin-Manuel Miranda.

Cowan cut her teeth organizing at Cesar Chavez’s side, on a farmworker unionizing effort in north San Diego County. “He taught me how to be fearless,” she recalled fondly. (Decades on, she remains friends with Chavez’s partner-in-organizing, Dolores Huerta, now 94 years old.)

In the mid-1970s, she, along with others, was prosecuted by the federal government for “aiding and abetting” undocumented immigrants. Cowan herself faced dozens of felony counts, one of which concerned giving an undocumented young woman a ride in her car to juvenile court so that she could seek permission to marry the father of her child. “That,” Cowan remembered, with a sardonic smile, “was a transporting charge.”

It was around this time that she got to know legendary civil rights lawyers such as New York’s William Kunstler. Cowan’s Tucson clinic—with its files, its colorful Central American fabrics hung over the windows, its grimy sofa coverings, its piles of folders and books, its disposable coffee cups and plastic containers of takeout food—bears more than a passing resemblance to Kunstler’s cluttered Greenwich Village office, which I visited in the mid-1990s as a young journalist. The charges were eventually dismissed and, after Jimmy Carter became president and the political climate became slightly less hostile for undocumented immigrants and would-be asylum-seekers, Cowan was made a certified representative, allowing her to represent people in immigration court. Her victory over the federal government made her something of a hero in Tucson. Over the decades, she built on that status to become one of the proudly liberal city’s most influential figures.

A few years after her successful fight against the feds, at the side of the storied immigrants’ rights attorney Peter Schey, who successfully sued Texas to establish the right of undocumented immigrant children to K-12 education, she witnessed the possibilities of immigration law to fundamentally transform community.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, she was the first attorney from Arizona to go into immigration detention facilities in California that were holding hundreds of Central American refugees, and was one of the first to start providing legal advice to those individuals—whom the U.S. government was determined to deport, since it was allied with the right-wing juntas of Central America as part of its Cold War efforts versus the spread of communism and didn’t want to alienate these governments by providing succor to their enemies.

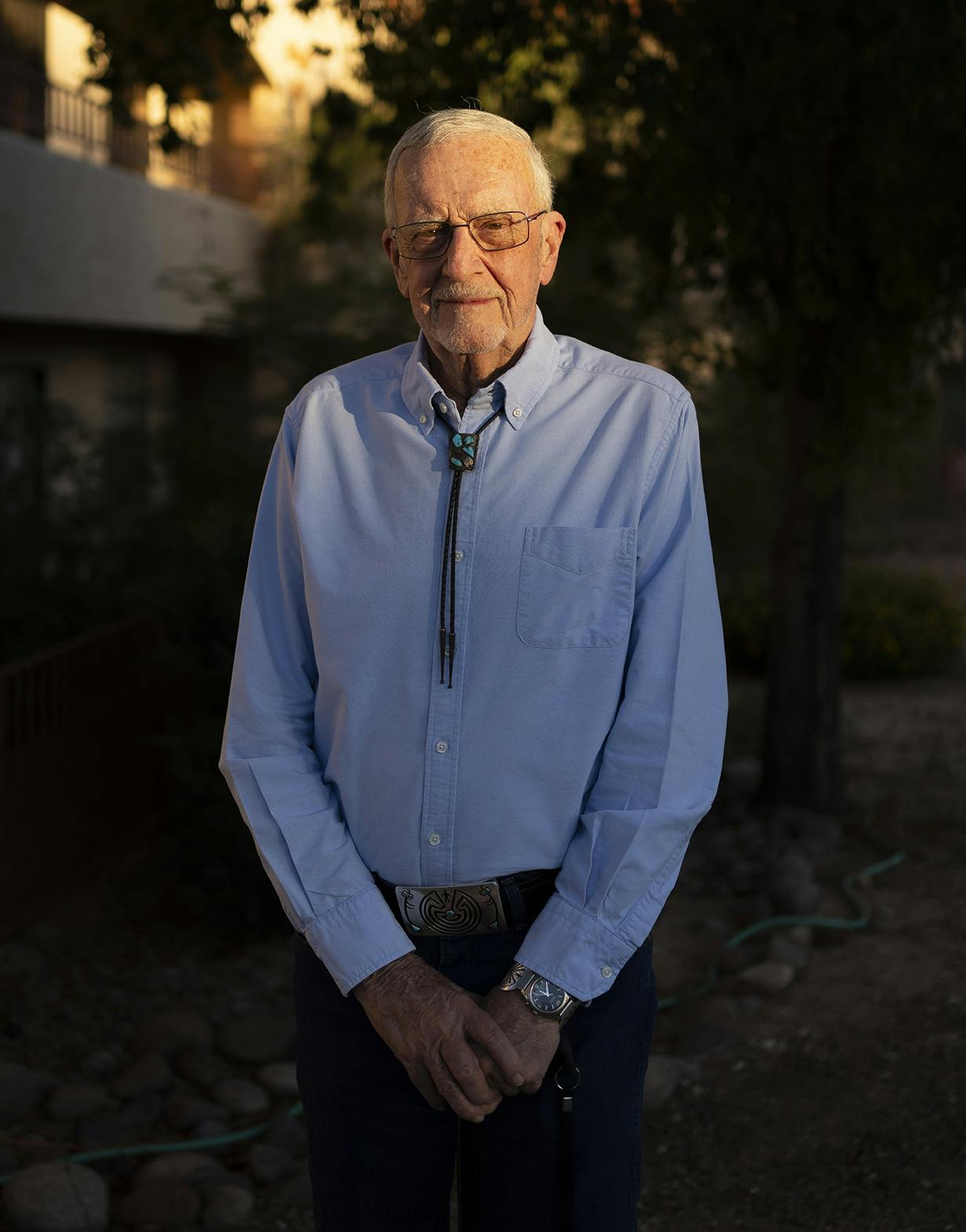

Shortly afterward, the young attorney began working with sanctuary movement founder the Reverend John Fife, then the pastor of the Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson, who helped smuggle across the border hundreds of refugees fleeing death squads in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala, and who built up a nationwide coalition of churches, synagogues, and other religious centers willing to provide sanctuary.

“We knew deportation could mean death,” recalled Fife—now in his eighties, his shock of hair fully white, his walk slowed by a recent injury, his handshake still bone-crushingly strong. He sat in a conference room off the church property’s central courtyard. “Margo was the first one to sound the alarm about Central American refugees being deported from El Centro [detention center] and said they needed representation. We organized the detention center to resist deportation.” In the mid-1980s, the federal government indicted Fife and more than a dozen others, including two Roman Catholic priests and three nuns, on aiding and abetting, transporting, and harboring charges. After a high-profile trial, eight of the defendants received five years’ probation; upon the trial’s conclusion, however, many publicly pledged to immediately return to their sanctuary movement work.

A generation later, Cowan and Fife were among the co-founders of the activist group No More Deaths, which in recent years has worked to try to prevent fatalities along the brutal migrant trails that snake through the Sonoran Desert and traverse the U.S.-Mexico border south of Tucson, often baked by temperatures soaring upward of 120 degrees. To the fury of the Border Patrol, as well as the plethora of right-wing militias that now patrol those desert lands, they helped set up water stations in the desert, engaged in food drops, and took four-wheel drives out into the wilderness to distribute emergency medical supplies.

All of this helped build up Cowan’s progressive bona fides. She became—and remains—close friends with Representative Grijalva, who for many years led the progressive caucus in Congress. (He declined to comment for this story.) She is tight with several ex-mayors. She is regularly fêted by leading progressive academics, journalists, and authors in the city. In 2021, the American Immigration Lawyers Association recognized her outstanding pro bono work for immigrants. She is also a onetime Museum of Contemporary Art Tucson “local genius” honoree.

Yet, as the numbers of desperate, impoverished undocumented immigrants skyrocketed, even a woman with Margo Cowan’s progressive chops and seemingly bottomless wells of energy struggled to keep up with the demand for legal services. The attorney’s “whole strategy,” Fife noted, “was to keep families in Tucson. Battling for their immigration and political asylum cases for as long as possible and doing it all for free.” That meant accepting a huge number of cases and, with scarcely any resources, hoping to somehow perform miracles.

Cowan’s bare-bones team at Keep Tucson Together—long on the sort of idealism that had inspired community organizing efforts from the 1960s on, but desperately short on resources—was, it seemed, floundering. It hadn’t filed a request with the IRS to qualify for 501(c)(3) status allowing for donors to deduct their donations (not until spring 2024 did it file for—and receive—this status), and, perhaps as a result, was perennially short of funds and unable to hire any salaried attorneys.

One of Cowan’s right-hand men, Ulises, an asylee from Mexico, sometimes, clients alleged, passed himself off as an attorney when dealing with them, despite his having no U.S. legal credentials. (Cowan and Ulises denied that this occurred, and it is certainly possible that, in the chaos of the high school clinic, some of these clients simply didn’t understand the difference between an attorney and a community adviser, and that in the heat of the moment Ulises didn’t bother to spend the time making clear the distinction.) In many ways, the wheels seemed to be coming off KTT’s bus.

Cowan’s organizing model resembles that of Saul Alinsky, whose legendary Industrial Areas Foundation taught organizers in poor communities to empower themselves through local work and on-the-ground campaigns; and she fervently believes that knowledge—in her case legal know-how—is to be shared with the community. She is, in many ways, on the side of the angels, a foot soldier in the campaigns for social justice that have helped transform so many American communities over the past 60 years. “Am I proud of the work we’ve done at this clinic?” she asked, and then answered her own question. “Yes, I am. I was fortunate enough to go to law school, and I have an obligation to share that knowledge with the community, not sell it.” When she goes to the supermarket near her home in the Barrio Hollywood neighborhood of Tucson, people stop her, she told me, to thank her for the work she has done, free of charge, on behalf of one or another family member. “That’s the magic you make in community,” she explained, “when your values are to keep families together. And so that’s what you do. And you don’t ever sell that. You just make magic.”

But while she is selfless with her work and with her time, she has a stubborn streak—which seems only to have gotten more pronounced with age—that some critics say lends itself to the belief that she, and only she, has the wherewithal to save these vulnerable people. Faced with a dysfunctional and often cruel immigration court system, an increasingly militarized border, and demagogic political rhetoric from Donald Trump and his allies regarding immigrants—faced too with state laws in Arizona that have empowered local sheriffs to go after people they suspect to be undocumented—Cowan has, over the past decade, responded in two ways: Firstly, she has tried to slow down the machinery, hoping that if she can delay her clients’ deportations long enough, eventually the laws will change in their favor, as they did in 1986, when President Reagan signed an amnesty for large numbers of undocumented in the country, and later when Central American asylees were granted temporary protected status and work permits. Secondly, on the not-unreasonable theory that, given the absence of other clinics in Tucson with a no-fees model for providing legal assistance to the undocumented, any representation is better than no representation, she has taken on as many cases as she possibly can—even though, realistically, one attorney working in her spare time and a group of community volunteers who mostly lack paralegal qualifications can’t possibly effectively represent hundreds, even thousands, of people simultaneously.

In the Trump era, with the president calling undocumented immigrants animals and predators, and as ICE agents rounded up undocumented immigrants without criminal convictions who had under previous administrations been low on the priority list for deportation, Margo Cowan was, it appeared, simply swamped by the needs of desperate people. Under American law, while the landmark Gideon case established a right to an attorney in criminal cases, there is no right to public counsel for most of those appearing in what Cowan contemptuously terms “crimmigration” court. In the absence of a federal right to counsel, Cowan has worked locally for years to persuade Pima County, where Tucson is located, to set up an office to pay for legal representation for the undocumented. But, at the same time, with no public moneys being spent on programs to help people navigate the immigration bureaucracy, and with her local efforts to expand guaranteed representation stuck in quicksand, out of good motives Cowan signed on as the attorney of record for more and more and more immigration cases. Driven by an almost obsessive idea that, for Tucson’s thousands of undocumented, she and her plucky team of volunteers represented the thin line between deportation and salvation, she was trying to represent so many indigent clients simultaneously that, in the end, critics allege that she hurt many of the sorts of people she’d spent more than half a century trying to help.

It was, many fellow attorneys came to believe, a cascading tragedy. “We have a crisis of representation, a lack of representation in Arizona, especially for non-detained people,” said one Arizona-based immigration attorney who was particularly critical of Cowan but wanted to explain the context out of which her actions arose. “My understanding is KTT has helped a ton of people. But her thinking is, ‘These people, they’re going to lose anyway; we’re just going to be a cog in the wheel and slow the process, and down the road there’s going to be reform.’ She doesn’t prepare the clients for the hearings at all. She takes on way more clients than she can handle. Individuals are sacrificed, and they’re sacrificed without their knowledge. People with viable claims aren’t being adequately prepared. Any attorney knows, you can’t expect to win a case if you don’t prepare it.”

That’s what happened to Juan Gonzalez Plata, a father of five who, in 2004, migrated to the United States as a 15-year-old, worked for years in restaurants and in construction, and ended up detained in the Eloy Detention Center in 2017. Cowan took on Juan’s case but then neglected to provide the courts with required information, including getting his fingerprints put into his court record. Because of the length of time he had been in the country, and because he and his wife had newborn twins, he had a strong case for the courts to cancel his removal order. But the judge denied his application, specifically citing Cowan’s failure to provide her client’s fingerprints to the court as the reason for his decision.

It is also what happened to Luis Ochoa, a young man with a trim goatee beard, who was represented by Cowan for nearly a decade. In 2018, Cowan called him out of the blue to tell him that his case, which had been closed during the Obama era, was reopened once Trump became president. Only then did Cowan learn that he had gotten married to a U.S. citizen, a development that ought to have made him eligible to apply for a green card. Cowan did not, apparently, follow through on this knowledge. To Luis’s surprise, by January 2021 he had received a deportation letter. Despite this glaring failure on the attorney’s part, the judge refused to grant an extension of the case.

Luis remains in the country, but he still lacks paperwork and knows that, unless his new attorney can convince a judge to let him file for a green card, he might well one day be separated from his family. It’s a bitter pill to swallow. He desperately wants the legal status, and the right to work, that his new attorney tells him he would now have had Keep Tucson Together done a better job with his case; and he wants to be able to travel to visit his father, in Mexico, whom he hasn’t seen since 2008, without fearing that he won’t be able to come back into the United States afterward.

As thunder clouds rolled into Tucson on a particularly hot and windy summer day, University of Arizona professor emeritus of law Andy Silverman sat in his second-floor office and pondered Cowan’s situation. Long a friend to Keep Tucson Together, Silverman is among the small group of local attorneys and law school professors who have frequently represented the clinic’s clients pro bono. He considers himself close with Cowan, whom he has known for more than four decades, yet reluctantly he has come to believe that in recent years she has bitten off more than she can chew. “Margo basically had two full-time jobs,” he explained: working at the public defender’s office, where she led the lawyers who represent Spanish speakers, and running KTT. “It was a lot—too much for anybody to really handle. Margo has this feeling that no one should go before the immigration court unrepresented, so she does everything she can.” This translated, he said, into a caseload that was “clearly into the hundreds,” without any paid staff attorneys to handle them. “It’s [just] Margo. I think a lot of us told her, or expressed concern, about the fact it’s just too many cases. There were mistakes made along the way. There were things that probably should have been done that weren’t done.”

In the years before the pandemic, the number of complaints against Cowan grew by leaps and bounds. There were allegations that, because of failures to file basic paperwork or to ensure that clients completed biometric requirements, men and women had lost their DACA or lawful permanent resident status. That asylum-seekers with viable claims had instead been ordered removed. That people who ought to have been able to adjust their immigration status because they were married to U.S. citizens or could prove that their deportation would result in extraordinary and unusual hardship for family members instead had their cases closed and were entered into the deportation process. That people with viable cases to stay in the country under the provisions of the Convention Against Torture had their appeal dismissed after no brief was filed.

In 2020, an adjudicating official, after completing a disciplinary hearing triggered by complaints from immigration court judges and members of the Board of Immigration Appeals, found that Cowan had “failed to manage her workload such that she could comply with court imposed deadlines.” In his scathing 45-page decision, Munish Sharda concluded that “the respondent’s misconduct injured her clients, the legal system, and the legal profession as a whole.” She had demonstrated a “lack of competency,” Sharda wrote, and exhibited a “failure to act with reasonable diligence and promptness” in representing her clients. He suspended her right to practice immigration law for a minimum of five years.

Cowan is tall and somewhat stout with age, her hair gray and cut short. Her lawyer, William Walker, suggested to the Arizona Daily Star that the actions against her were motivated by the Trump administration’s effort to deprive immigrants of representation. “This isn’t about Margo Cowan,” Walker told the Star. “This is about an administration that has wanted undocumented people thrown out of this country.” Cowan appealed the decision, and in 2023 the suspension was reduced to two years. The Arizona Daily Star reported that on 11 counts, “the government claimed Cowan failed to provide specific grounds for an appeal” for the decisions against her clients. She also “failed to file an appeal after stating an intent to do so in the Notice of Appeal,” and “did not timely notify the board that she didn’t intend to file an appeal in any of the cases listed in the Notice of Intent.” Yet, even with the reduced penalty, Cowan continued to be vocal in her views that the sanction was unjust and that border officials and conservative judges, who had long opposed activist groups that stood on the side of the undocumented, were looking to remove an effective thorn in their sides. The longtime attorney-activist wouldn’t, maybe couldn’t, admit that she and the team of community volunteers had made any mistakes along the way.

Meanwhile, however, her erstwhile colleagues at No More Deaths, which had long marched to the same tune as KTT, lost patience. They were no more sympathetic than was Margo Cowan to the immigration courts and to the government agencies that policed the border and targeted community members for deportation, yet as the pandemic raged they became convinced that Cowan’s team was responsible for a growing number of serious legal errors.

In 2022, No More Deaths severed ties with KTT, announcing that the number of cases alleging inadequate counsel was simply too great to ignore. “The stories shared by the families are devastating and we honor their bravery in coming forward,” the group’s statement read. “After several requests for information and exhaustive efforts to hold KTT accountable internally, we have decided to no longer be associated with services provided by KTT.”

Cowan continues to defend her methods. “When you’re a community organizer, you organize a model that meets the needs of the community,” she argued to me. “I am a lawyer, but I’m first and foremost an organizer. You don’t turn anyone away. You don’t. You organize. That’s what you do in community; you tie up shit until there’s something else.” Her helper, Ulises, agreed. “As long as God gives us license, we’ll continue to fight,” he said. “I won an asylum case for myself, and I know how scary it is to go to court—and what awaits me if I’m deported, and what awaits these people who I prepare forms for.”

By Cowan’s reckoning, she has long filled a void: giving free legal counsel to impoverished immigrants, many lacking not only legal status but basic documentation, and trying, against the odds, to rescue as many of these poor souls as she can. She is, in her mind’s eye, a fearless warrior for social justice. Of course, she argues, in perhaps her only concession to the messy realities of the case against her, it would be better if the initiative that she has pushed to get on the ballot for years now—that would mandate Pima County to guarantee the right to counsel for indigent immigrants as they go through the notoriously byzantine immigration courts, and that would fund an office devoted exclusively to this—were to pass. It would be better if the undocumented community didn’t have to rely on KTT. But each election cycle that she and her allies have tried to get the initiative on the ballot, the coalition has failed to gather enough signatures to qualify it for a vote. And so, absent representation paid for by the county, and absent any other law clinics that will guarantee free representation to the immigrant poor, Cowan and her team struggle on, taking delight in organizing methods that they see as pissing off the powers that be, and issuing broadsides against critics both from within the government and from within the immigrants’ rights and legal communities in Tucson.

“When you start standing with people, the show ain’t smooth,” the aging attorney told me, in a small conference room of her cluttered Keep Tucson Together offices. Interviewed by local journalist Todd Miller on the podcast The Border Chronicle in September 2023, Cowan told listeners that she had created “a lot of animosity” among judges by gumming up the works, that she was representing people who previously didn’t have counsel and thus could be deported after only two or three hearings.

As for the allegations from ex-clients, the KTT founder argued that the fault was usually theirs, that they didn’t provide needed documents, didn’t let her know when they moved homes, missed court dates, and so on. “We are always there when we say we’ll be there, and we always produce when we say we’ll produce,” Cowan told me. “And if we don’t produce it’s because the client didn’t come in and sit with someone and bring in the documents. Clients didn’t do what would allow us to produce the work. I have not seen one complaint yet that has been valid.” These clients, she said, were free to go elsewhere, but were in “good positions” with her as their attorney.

Not surprisingly, Evans-Schroeder—who years ago did volunteer work for Cowan’s DACA and Naturalization Fairs and expressed a healthy appreciation for Cowan’s efforts to get public funding for immigration attorneys—disagrees. She wants to admire the Keep Tucson Together founder, but over the past several years she has come to the conclusion that Cowan, despite her storied past, has harmed so many clients that her suspension from practicing immigration law is merited. “She sacrificed them,” Evans-Schroeder told me in frustration. “She was trying to make a statement, but at what price?”

Cowan isn’t wrong that the immigration court system is broken. Nor is she incorrect in saying that the lack of right to counsel is a scandal. After all, in the criminal justice system a person has a right to counsel no matter the triviality of the case against them; in the immigration system, however, where a court decision can permanently uproot lives, fracture families, and deprive people of livelihoods and of homes, there is no such right. In a city such as Tucson, which is only an hour’s drive from the Mexican border, and which has long been a key stopping point on the journey north, this fact leaves tens of thousands of people particularly vulnerable to the ever-changing whims of federal immigration policy, of law enforcement, and of popular opinion. That knowledge, however, seems to have driven Cowan and her KTT colleagues, in their aim to serve as many people as possible, to take shortcuts with immigration cases; and those shortcuts over time hurt a growing number of people.

“Every time I phoned her, I never got a call back. She never returned my email,” said Dulce Alvarado, who was brought into the United States by her parents when she was a young girl and became a permanent resident in 2010, after qualifying for a work permit under the Violence Against Women Act—she had suffered for years at the hands of her violent partner. Then, in 2019, she lost her legal status after being detained (although not convicted) on suspicions of people-smuggling connected to illegal activities engaged in by one of her close friends. “I lost peace, I lost a lot of weight. I was very depressed. I’d end up in the hospital every so often.”

Dulce, who is now a pro bono client of Evans-Schroeder, said that she gave all her personal documents to KTT, including those detailing her interactions with the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services over the years, but that, in the course of her many deportation hearings, it filed hardly any relevant paperwork with the courts. “She was all over the place and was just losing everything,” she recalled of Cowan. Finally, Ulises told Dulce that she had to show up for a court hearing—but allegedly neglected to tell her that it was her final hearing, the one that could result in her deportation. He promised her that Cowan would show up, but she showed up so late that Dulce was already in conversation with the judge. The defendant stated on the record that she was unhappy with her legal representation. And then, she recalled, Cowan walked out of the courtroom.

As of this writing, Cowan is not allowed to practice before the Board of Immigration Appeals, the immigration courts, or the Department of Homeland Security—though she still visits Keep Tucson Together on a regular basis, and attends the weekly clinic at Pueblo High School.

In the wake of the decision that suspended her from practicing immigration law, the floodgates opened. Suddenly, immigrants who had long been dismissed or ignored were getting their stories told. A number of private attorneys stepped forward to try to undo the damage that Cowan’s allegedly inadequate counsel had caused. In some cases they did, as Cowan had always argued they would, charge thousands of dollars for their services. In other cases, they worked pro bono or charged clients on a sliding scale. Against the odds, many of those men and women got their deportation orders reopened on appeal, having successfully shown that they received “ineffective assistance of counsel” from Cowan and her KTT team.

Dulce Alvarado was one of the lucky ones. Her hearing was extended by a month, and Evans-Schroeder’s team prepared all the files and gathered all the necessary documents, submitted her youngest child’s birth certificate, produced proof of her elder son’s epilepsy, documented the extreme abuse she had suffered at the hands of her onetime partner. At the end of the process, the judge canceled the removal order.

“I’m trying to get my life back,” Dulce, who is currently applying for jobs, said simply. “Because I lost it this whole time this happened. I lost Dulce down the road and I’m trying to still find her daily. I live with hope the Dulce that was lost will come back.”

Ultimately, this is a story of good intentions gone awry. “Anything she’s done has been out of her feeling of what needed to be done,” Silverman said, talking of his friend’s efforts over the years to plug the gaps of a broken, dysfunctional, and often merciless immigration system. “She’s very devoted to the migrant community and always has been.”

Cowan’s is a story of who has power and who is left vulnerable in an immigration system burdened by historically large numbers of cases, and in an era in which the undocumented, fleeing poverty, government and cartel violence, environmental collapse, and political dysfunction, have been increasingly demonized by demagogues such as Trump and Arizona’s own Kari Lake, by Fox News, by rifle-toting militias and self-aggrandizing county sheriffs. It’s also a story of human fallibility and self-destructive pride: the septuagenarian Cowan’s refusal to acknowledge that, after a half-century working in a pressure-cooker environment, she was overwhelmed; that her desire to push through despite not having the resources had ultimately ended up harming the very people she had devoted her life to and, finally, led to her fall from grace in the immigration courts. And it’s a story of friend pitted against friend in Tucson, where No More Deaths has very publicly distanced itself from Cowan and KTT.

“I’m using up my leave time and then I’ll probably retire,” Cowan said. When asked what she wanted her epitaph to say, she had no doubt: “She was a good old girl,” the attorney told me, pondering her nearly 60 years on the community organizing front lines. “That’s the line. ‘She was a good old girl.’”

Others, however, aren’t so sure. “I don’t want to believe that she just doesn’t care,” said Dulce, her hair tied back, her eyebrows carefully sculpted, looking far younger, now that she is no longer worn down by daily panic, than her 43 years. “Maybe she just had a lot of cases in hand and had to deal with a lot of people. But she was just going around the bushes with me, and I don’t know why. I forgive her. I bless her and I bless her soul for being who she is. But I hope that if they [KTT] are still operating, they’re taking care of the people who need her assistance. Not to feel hope and see the light at the end of the tunnel is the worst feeling a person can go through.”