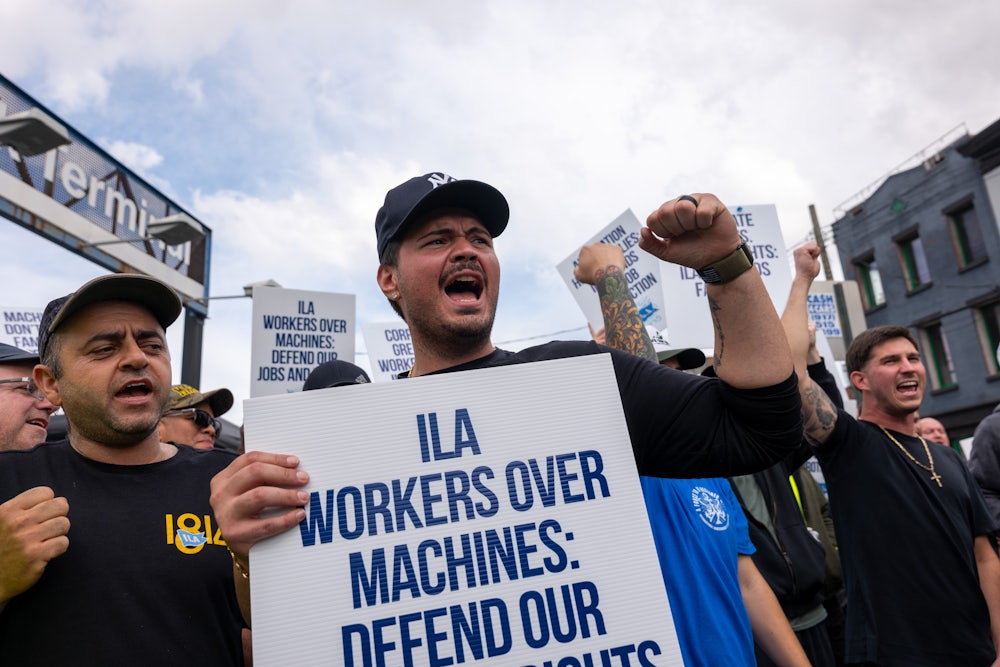

Globalization has been a catastrophe for just about every industrial worker in America except dockworkers. People who make things no longer occupy much of a choke point in our economy, but people who transport things still matter a great deal. Hence the tendency for recent large strikes (and threatened strikes) to involve people in the business of moving stuff around: United Parcel Service, railroad workers, stevedores. That is the reality—leverage—behind the strike begun Tuesday morning by 47,000 dockworkers, all represented by the International Longshoremen’s Association, or ILA, and all situated along the Eastern Seaboard and the Gulf Coast. The dilemma faced by both presidential candidates is what to say about it.

Dockworkers have more clout than other transportation workers because they’re more concentrated spatially (in ports) and therefore easier to unionize; because ports don’t lend themselves to deregulation, something trucking, railroads, and airlines underwent starting in the 1970s; and because nearly every import must arrive by boat. Export or import, it’s all the same to the dockworker, on whom the $79 billion U.S. trade deficit weighs lightly.

The container ships that dockworkers load and unload keep getting bigger. By one estimate their capacity has grown, since their introduction in the 1950s, by 2,900 percent. In August the country’s 10 largest ports increased inbound volume more than 19 percent over the previous year, according to industry analyst John D. McCown.

Dockworkers represented by the ILA earn a base pay of $81,000, and the most senior can earn, with overtime and benefits, up to $200,000. The ILA is asking for a 61.5 percent pay raise over the life of the six-year contract, along with certain limits on automation. That’s an aggressive demand, but shipping industry profits exceeded $400 billion in each of the previous four years. “They don’t want to share it,” ILA President Harold Daggett complained to CNN.

You can be forgiven for thinking dockworkers are forever going on strike, or threatening to do so. That’s true of West Coast dockworkers, who handle the majority of U.S. imports and are represented by the more militant International Longshore and Warehouse Union, or ILWU, founded by Harry Bridges, a radical whose ties to the Communist Party prompted the CIO to expel the ILWU in 1950. (The ILWU rejoined the combined AFL-CIO in 1988, then quit it again in 2013.) The ILWU went on strike in 1971, 2012, and, very nearly, last year, when it engaged in a series of work slowdowns before Acting Labor Secretary Julie Su helped negotiate a contract.

The ILA, on the other hand, hasn’t gone out on strike since 1977, when dockworkers walked out for 45 days. The ILA can be faulted on other grounds (past involvement with organized crime, famously dramatized in the 1954 film On the Waterfront; mob ties are said to linger in the ports of New York and New Jersey). But given that the ILA represents workers who move close to half of all U.S. imports, the union has been very restrained in its dealings with management compared to the ILWU.

For Kamala Harris and Donald Trump, the timing of this strike is very inconvenient. The interruption of supply chains and its potential impact on inflation must be music to Trump’s ears. But if Trump publicly mentions the strike he’ll be expected to say whether he supports it, and it would be foolhardy for Trump to state out loud that he doesn’t (even though this is almost certainly his opinion) because that could cost him some working-class support.

For Harris, however, the strike is an opportunity to declare solidarity with union workers, something she does far too little. But the inconvenience that the strike may cause consumers, especially on prices, likely terrifies Harris, who has hesitated to challenge the Republican narrative that inflation is out of control.

The Teamsters, who last month declined to endorse either presidential candidate, issued a press release backing the ILA and bluntly warning the Biden administration to “stay the fuck out of this fight.” (The press release used asterisks for the u and the c, but the warning was still pretty crude.) The union justified not endorsing Harris in large part on the (dubious) pretext that the Biden administration used its legal authority to force ratification of the rail workers’ contract way back in 2022.

President Joe Biden has similar authority, under the Taft-Hartley Act, to force the ILA to end its strike, as President George W. Bush did in 2022 to end an 11-day ILWU lockout at the West Coast ports. But Biden has stated, wisely, that he has no interest in intervening. “I don’t believe in Taft-Hartley,” Biden told reporters. “Now is not the time for ocean carriers to refuse to negotiate a fair wage for these essential workers while raking in record profits,” the White House added in a written statement.

A good question for J.D. Vance in tonight’s vice presidential debate would be whether he agrees with a letter that 69 House Republicans, including the chairman of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, sent Biden urging him to “utilize every authority at its disposal [italics mine] to ensure the continuing flow of goods and avoid undue harm to American consumers and the nation’s economy.”

Senator Vance, do you favor using Taft-Hartley to force an immediate end to this strike?

Should the same question be directed at Tim Walz, here is how he should answer:

I oppose invoking Taft-Hartley, a law that would be largely repealed by the PRO Act, a bill to expand worker rights that I favor. As governor, I signed into law similar legislation. I would urge the maritime industry to use its $400 billion in annual profits to resolve this dispute quickly, because dockworkers deserve their fair share.

Walz probably doesn’t need my help, but something tells me Harris does. I hope somebody is writing this down for her.