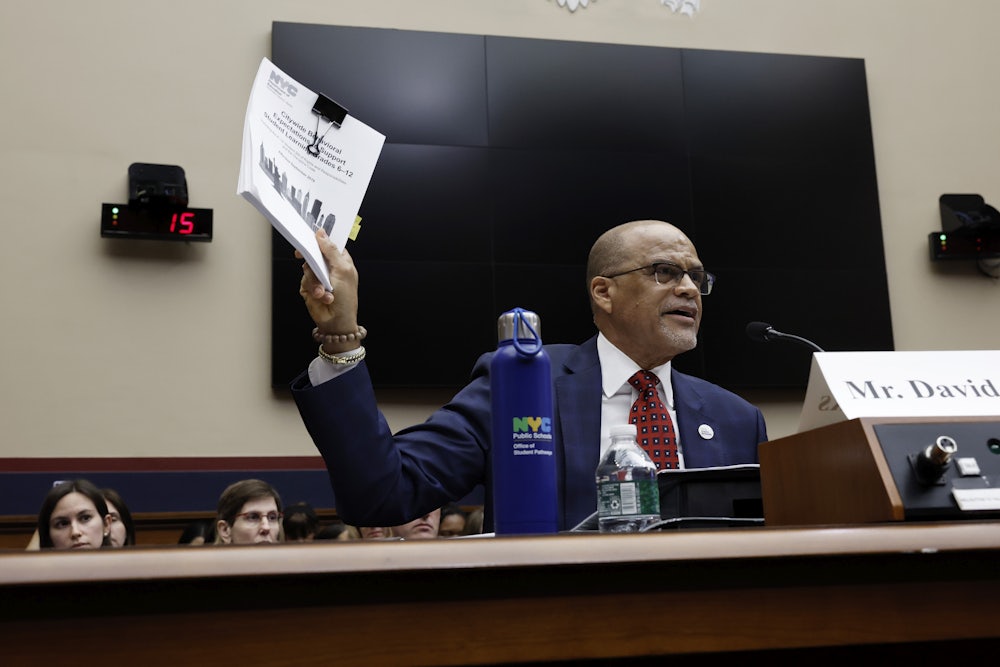

Last week, when New York City Schools Chancellor David

Banks sat for an interview with The New York Times, the big

headline was that he called New York City’s newly arrived migrants a

“godsend” to a school system that has been losing enrollment. The comment would

be received as an unremarkable commonsense statement if we did not live in

such a fascist-adjacent society.

But Banks did say something that should genuinely worry those concerned about the future of this country. When reporter Troy Closson asked Banks about “his vision for the system,” Banks said artificial intelligence “can dramatically affect how we do school in the first place.”

Sure, it can, but it should not. Our children shouldn’t be taught by robots. This should go without saying, but Banks’s interview shows that we do, in fact, need to be saying it. Asked to elaborate about what he meant, Banks said that “the immediate stuff is really around personalized tutoring and support.” Trying, like every other good neoliberal before him, to sell us on a potentially unpopular idea, he added, “You can have almost your own bot that can be a personal assistant to you.”

This sales pitch sounds familiar. Over the last 40 years of political life, politicians have frequently portrayed their attempts to starve the public sector as a shiny, new, and exciting opportunity for everyone, just glistening with choices. In reality, Banks—and the technobillionaires he’s speaking with—view bots as a cost savings, a route to fewer teachers.

It’s disturbing that Banks volunteered this nonsense without even being asked about A.I. He was asked what his “vision” was, apart from making sure every kid learns how to read. Ensuring universal literacy is, of course, a fine vision. So he could have said, “What else is there? Reading is fundamental.” He could have talked about making every school into a place where kids feel happy and safe and look forward to going every day. He could have said something about STEM. That he offered this A.I. snake oil as his response to a question about “vision” is both ridiculous and troubling, especially considering that New York City often serves as a laboratory for education policy ideas (whether bad ones, like getting rid of elected school boards, or good ones like universal school lunch).

Bots can’t teach. They can provide information—as anyone knows who uses Chat GPT for research—but the information isn’t necessarily of the highest quality, and, regardless, providing information is not the same as teaching. Teaching is a relationship between—or among—humans. Research shows, and everyone who spends any time around schools and children knows, that kids succeed or fail in school based on the relationships they find there, especially with the adults who can guide them. The teacher who sees their potential. The basketball coach who helps them see that they need to keep up in their studies. Schools need many more such adults, not fewer.

It’s hard to imagine anyone would look at the youth in our world today and conclude that they need more machines in their lives. Our kids are anxious and depressed, and these mental health issues are a huge factor in many dropping out of school. Of course, climate change is one reason, but it’s not the only one. Loneliness—which research shows is linked to anxiety and depression in kids—is another, and the internet is part of the problem. Even before the pandemic, the trends here were worrisome; a study of high school seniors from 1976 to 2017 found less in-person socializing and a 50 percent increase in feelings of loneliness (this sad trend spikes sharply after 2011, reflecting general adoption of social media). Some governments are beginning to take the problem seriously, to the degree that the Australian government is considering an age limit to prevent children and tweens from using TikTok or Instagram. Whether or not that’s the right approach, one thing’s certain: Kids need people.

What’s particularly galling is that as our school leadership entertains these ludicrous and harmful ideas about our children’s education, they’re also wreaking havoc with those children’s future. I’ve written before here about A.I.’s indefensible climate impact, which the industry is reluctant to discuss in detail. Even without full disclosures, we certainly know enough to tell that it’s a colossal and perilous waste of water and energy—all for no good reason.

Luckily, Banks doesn’t sound like he has any idea what he wants to do in policy terms. He said, “As it relates to the student experience, I think we are just beginning to conceive of how dramatic a change A.I. can make. I don’t even know what it means just yet. But I’m leaning in, and I’m studying.” In other words, Banks’s A.I. policy is even below the level of “concepts of a plan,” to quote the much-memed health care response Donald Trump gave in the presidential debate. Once the venture capitalists and tech bros get involved, though, it will be harder to keep it that way.

Perhaps one reason Banks’s comments on A.I. haven’t stoked more outrage is that they’ve been overshadowed by even more shocking events. The day before the Times published that interview, federal agents seized David Banks’s phone—as well as that of his fiancée, who is first deputy mayor, and those of his two brothers, one of whom is a top aide to Mayor Eric Adams, while another is a consultant. It was part of what appears to be an enormous investigation into possible corruption in the Adams administration. The police commissioner, also under investigation, resigned Thursday. On Friday, the Daily News ran photos of the Banks brothers at a Jets game with a notoriously corrupt businessman who later went to prison for bribery. Given all this, it wouldn’t be surprising if Adams and some of his closest advisers—a small circle that includes Banks—went to prison, or at least lost the next election. Unfortunately, however, even if Banks goes away, A.I. itself won’t get out of our schools without a fight. Teachers’ unions and parents need to start waging war on machine learning now.