In the 1960s, Arthur C. Clarke was the face of futurism. A deep-sea explorer, inventor, and science-fiction author, Clarke dazzled Anglophone audiences with visions of global computer and satellite networks, space travel, and artificial intelligence. Against his boundless technological optimism, the Cold War could appear but a blip. This sleight of exuberance drove interest in his Wellsian articles and essays, collected in 1962’s Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry Into the Limits of the Possible. The adages that anchor that book—“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”—appeared just as a 14-year old prodigy named Ray Kurzweil was teaching himself to build computers in his family home in Queens, New York. Six decades later, Kurzweil still quotes Profiles of the Future in his lectures and writing. And when it comes to understanding Kurzweil’s signature idea—the merging of human and artificial intelligence that he calls the Singularity—it’s useful to look at the screenplay Clarke wrote with Stanley Kubrick a few years later.

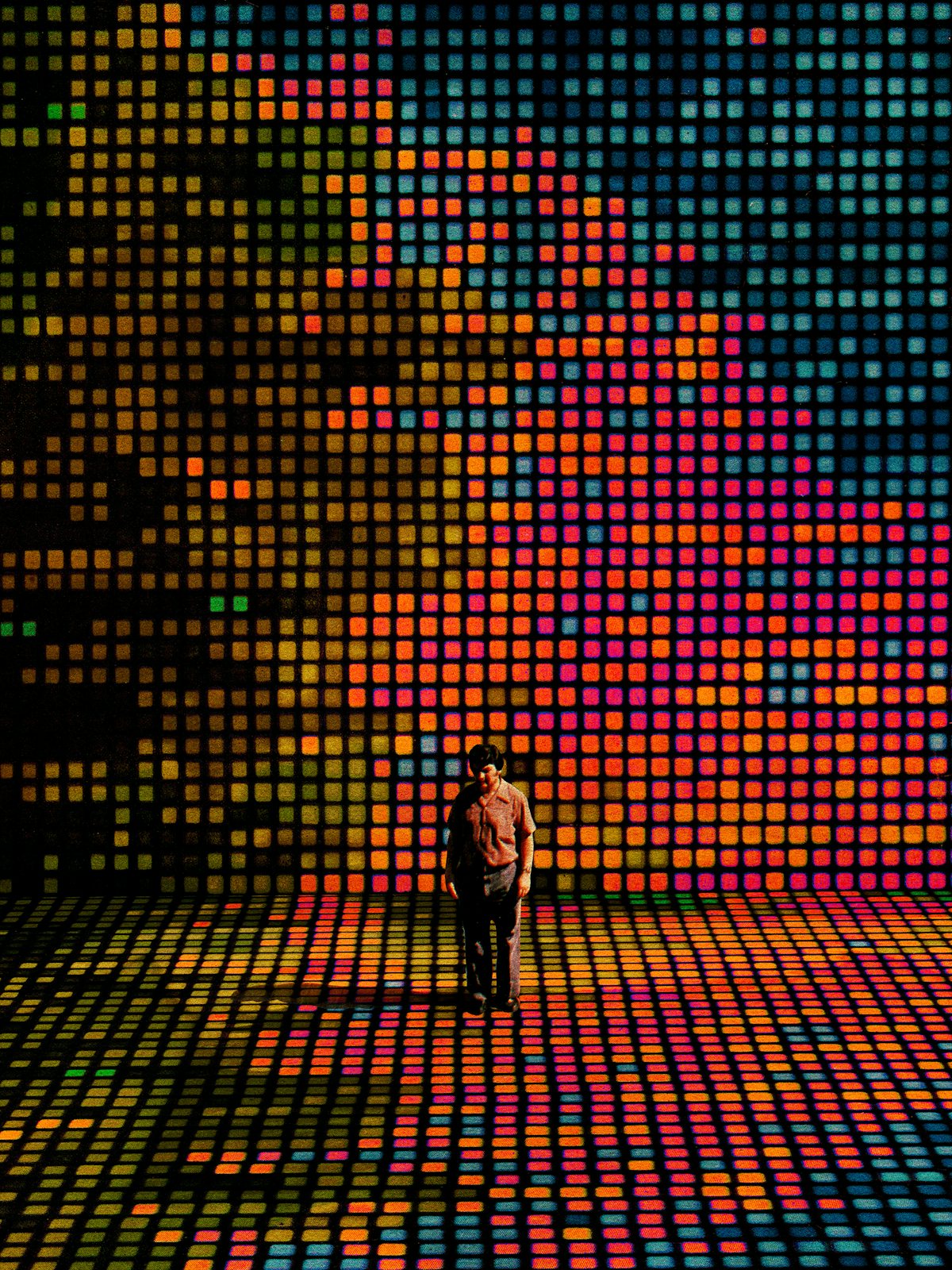

Since the release of 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968, public expectations and fears of sentient AI have generally looked like HAL 9000, the film’s glowing red dot of artificial consciousness in charge of operating the spacecraft Discovery One. The HAL model of computer-based intelligence is basically a murder-machine: an unpredictable, hostile “other” that turns on its creators. It reappears in the red pupils of Skynet Terminators, the dollhouse revolts of M3GAN and Ex Machina, and in the cautionary scenarios of a growing legion of AI doomers. For Kurzweil, however, HAL-like sentience was always a mile marker, not an endgame. His career as a futurist can be seen as an attempt to correct his late friend’s enduring depiction of AI as an external threat, and prepare the public for an inconceivably grander and weirder fusing of carbon- and silicon-based intelligence. In 2001 terms, the Singularity isn’t HAL—it’s the psychedelic interspecies wormhole of the film’s sublime third act, “Beyond the Infinite.”

Kurzweil’s Singularity is somewhat hard to pin down by design, its name stolen from the spookiest frontiers of knowledge. In mathematics, it refers to when the model falls apart; in astrophysics, it is the infinitely dense and mysterious center of a black hole, where the laws of physics do not apply. The Singularity Is Nearer is Kurzweil’s fourth book explaining the inexorable logic he believes has brought us to the doorstep of the brain’s first evolutionary leap since the cerebral cortex began expanding two million years ago. If such a thing is possible, it finds him even more confident in his prediction, first made in 2005’s The Singularity Is Near, that the titular event will be achieved by midcentury.

“We will extend our minds many millions-fold by 2045,” writes Kurzweil. “We are finally getting to the steep part of a fifty-year-old exponential trend…. Humanity’s millennia-long march toward the Singularity has become a sprint.” Kurzweil’s optimism is an energetic counterpoint to the darkening public temper around AI and its specters of deeper oppression and immiseration, never mind the alarms being rung by brooding AI researchers haunted by visions of HAL, who warn the road ahead is elaborately booby-trapped with extinction risks. For Kurzweil, the Singularity still promises only deliverance—from our most intractable problems and the crooked timber that produced them. As the field he helped build rumbles with doubt, Kurzweil is the most prominent spokesman for AI messianism.

When Kurzweil speaks at conferences and summits around the world, he is often introduced as having worked in AI longer than anyone else living. To be precise, he has been active in the development of AI for 61 of his 76 years. In high school, Kurzweil, the son of a conductor, built a computer and programmed it to produce original piano music in the style of dead classical composers. Word of his genius spread, leading to summonses from the giants of the young field, most notably Frank Rosenblatt of Cornell, who invited the teenage Kurzweil to work on a pioneering “neural network” called the Perceptron, and Marvin Minsky, who would become Kurzweil’s mentor and collaborator at MIT.

When Kurzweil was starting out in the 1960s, limited computing power constrained the ability to test early models of “machine learning” such as Rosenblatt’s Perceptron. But Kurzweil never doubted computers would catch up. In 1965, the year Kurzweil enrolled at MIT, Gordon Moore published an article predicting that the number of transistors on computer chips would continue doubling every two years at flat or falling cost, and computers would rapidly improve. As a result, Kurzweil spent his early career laying intellectual foundations for technology decades ahead of its time. He and his peers anticipated but could not yet realize the potential of computerized neural networks; they theorized a “connectionist” paradigm, which understands intelligence as emerging from a complex but replicable web of neuronal relationships in the human brain. (AI programs such as ChatGPT have recently emerged from connectionist blueprints drawn up in the 1950s and ’60s.) Even before these networks became possible, Kurzweil’s peers surmised these networks would eventually enable novel forms of computing to shatter the physical limitations of the transistor. The year Moore’s article appeared, the AI researcher I.J. Good was already thinking ahead to a coming “intelligence explosion” that Kurzweil would later name the Singularity.

While waiting for Moore’s Law to gain speed, Kurzweil stayed busy. As an undergraduate, he started a company that matched high school students with prospective colleges, using a computer program he developed. He sold the company before graduation, the first of what would become a dizzying number of companies, products, and patents racked up by Kurzweil over the course of an inventor’s career that has drawn comparisons to Edison. His best-known work during the 1970s and ’80s involved character and pattern recognition; it birthed the flatbed scanner and the first reader for the blind. The latter invention led to a friendship with Stevie Wonder, who challenged Kurzweil to create a synthesizer that could mimic the pristine sounds of acoustic orchestral instruments. The result was the Kurzweil 250 and a Technical Grammy Award.

All the while, Kurzweil carefully tracked technological megatrends the way a field artilleryman studies the geometry of a distant moving target. His interest was mostly practical. Why waste time on research unless it was aligned with existing or soon-to-exist technology and levels of computing power? Then, in the mid-1980s, Kurzweil detected a warping in the rate of technological advance. Moore’s Law, he noticed, was being outstripped, and mightily, by a plummeting price-performance ratio. He concluded that this process—which as of this writing has multiplied computing power 20 quadrillion times in 80 years—was racing toward the AI-fueled “intelligence explosion” foreseen by Good. One couldn’t say it was ahead of schedule, exactly, because there was no schedule until Kurzweil started writing about it. In The Singularity Is Nearer, Kurzweil describes his epiphany that machine learning systems would soon begin improving themselves by designing ever more powerful neural networks.

“Because computers operate much faster than humans, cutting humans out of the loop of AI development will unlock stunning rates of progress,” writes Kurzweil. “Artificial intelligence theorists jokingly refer to this as ‘foom’—like a comic book–style sound effect of AI progress whizzing off the far end of the graph.”

The publishing result of this insight wasn’t a comic book, but a heavily illustrated anthology that announced Kurzweil’s arrival as a futurist. Appearing in 1990, The Age of Intelligent Machines gathered essays by leading AI researchers, including Minsky, to introduce the public to neural networks—how they worked and what they would soon be able to do. By the standards of Kurzweil’s mature vision of the Singularity, the book’s claims for the future are tepid. He predicts 1997 as the year a computer chess program would defeat a human grandmaster (and he was close—it happened in 1998), but he isn’t yet talking about defeating Death, Seventh Seal–style, at the same game board.

His forecast was much bolder in 1999’s The Age of Spiritual Machines, Kurzweil’s first work of full-throttle futurism and his coming-out party as a transhumanist. At a time when most people still did not use email, he declared that the law of accelerating technological returns made a merging of man and machine inevitable, and that within two generations nanotechnologies would enable “rebuilding the world, atom by atom…. body and brain will evolve together, will become enhanced together, will migrate together toward new modalities and materials.” The book also debuted Kurzweil’s claim, deemed preposterous at the time by many, that the first AI would pass a basic version of the Turing test by 2029. In The Singularity Is Nearer, Kurzweil notes his prediction was not preposterous enough. To appear convincingly human, an AI in 2024 has to intentionally dumb itself down.

The stage was thus set for Kurzweil’s 2005 opus, The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology. A brain-bending work of popular science, the book elevated the profile of both Kurzweil and transhumanism. It posited the Singularity as the natural culmination of a billions-of-years-long story of information organizing itself from chaos in increasingly efficient units. It is a story spanning six epochs, beginning with the formation of atoms shortly after the Big Bang, and continuing into the soon-to-arrive fifth epoch defined by the law of accelerating technological returns and the first merging of biological and artificial intelligence. The sixth and final epoch will be fully transhuman, defined by the proliferation of “exquisitely sublime forms of intelligence … the ultimate destiny of the Singularity and of the universe.”

The Singularity Is Near was a bestseller and spawned two films. The first, Barry Ptolemy’s Transcendent Man, is a traditional documentary and a good introduction to Kurzweil’s life and work. The second, a docudrama starring Kurzweil’s computer-generated female alter ego, “Ramona,” and featuring Tony Robbins and Alan Dershowitz, has unfortunately been scrubbed from the internet, along with the video of “Ramona”/Kurzweil regaling a 2001 TED audience with a rendition of the Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit.”

Now 76, Kurzweil has reemerged on the book circuit as a more restrained kind of character, with outward signs of eccentricity limited to sartorial touches like colorful hand-painted suspenders and Tudor Renaissance flat caps. Unchanged is his belief in the Singularity by 2045. The Singularity Is Nearer is less a sequel to The Singularity Is Near than a progress report on the intact megatrend of accelerating technological returns. It is also a forceful restatement of Kurzweil’s conviction that transhumanism represents not the death of humanism but its fullest flowering.

“Merging with superintelligent AI,” he writes, “is a means to a higher end”:

Once our brains are backed up on a more advanced digital substrate … our behaviors can align with our values, and our lives will not be cut short by the failings of our biology. Finally, humans can be truly responsible for who we are….

Death “prevents us from enjoying more of the transcendent moments that define us—producing and appreciating creative works, expressing a loving sentiment, sharing humor. All of these abilities will be greatly enhanced as we extend our neocortex into the cloud.”

The idea of silicon-enhanced, cloud-based human self-actualization is the antithesis of humanism as we know it, a tradition that has generated mostly critiques of technology and machine logic rather than celebrations. Kurzweil has no more use for what he sees as antiquated critiques of technology than he does for romantic odes to mortality. For him, death is not the mother of beauty, as Wallace Stevens wrote, but its nemesis. With the death of a loved one, “the neocortical modules that were wired to interact with and enjoy the company of that person now generate loss, emptiness, and pain. Death takes from us all the things that in my view give life meaning.” If not always patient with them, Kurzweil is resigned to the persistence of rearguard humanist critics, who question the building of intelligent machines and see hubris in attempts to engineer our way out of social crises and the human condition itself.

Many of these arguments contain echoes of Lewis Mumford, the twentieth-century grandee of humanist critiques of techno-industrial society, who warned that any intelligent machines will “bear the stamp of the human mind, partly rational, partly cretinous, partly demonic.” Kurzweil has always reveled in locking horns with modern-day Mumfordians who denounce the Singularity as a terrifying caricature of techno-optimist delusion, and he devoted a long chapter in The Singularity Is Near to grappling with antagonistic theologians, Marxists, Malthusians, and AI-skeptical philosophers of consciousness. (John Searle’s influential “Chinese Room” dismissal of AI alone received 10 pages of point-by-point rebuttal.)

Nearer lacks a full fight card of rematches, but Kurzweil does return at length to the “hard problem of consciousness,” which asks how AI consciousness can ever be “proved” when we don’t even understand how human brains give rise to the subjective experience that philosophers call qualia. Kurzweil’s argument, first laid out in his 2012 book, How to Create a Mind, rests on the assumption that the subjective self is a product of computation. All that is required to create qualia in nonbiological mediums is a sufficient duplication of this computing model. While some AI theorists believe “whole-brain emulation” will require understanding and copying human brains at the quantum level, Kurzweil is not one of them. “Subjective consciousness,” he writes,

likely stems from the complex way information is arranged by our brains, so we needn’t worry that our digital emulation doesn’t include a certain protein molecule from the biological original. By analogy, it doesn’t matter whether your jpeg files are stored on a floppy disk, a CD-ROM, or a USB flash drive—they look the same and work the same as long as the information is represented with the same sequence of 1s and 0s.... One of the major research projects of the next two decades will be figuring out what level of brain emulation is sufficient.

Even if the nature and origin of consciousness can never be settled in a way that satisfies the requirements of scientific definition, Kurzweil believes we know enough to begin desacralizing biological qualia. For him, both carbon- and silicon-based consciousness are intensely complex forms of information that emerged from chaos and thus command reverence. One is conjured by eons of biological evolution, the other by thunderbolts of technological advance; both represent a “fundamental force of the universe.” If the math adds up, outward signs of consciousness should be taken seriously as evidence of a subjective inner life, in both original AI consciousnesses and “replicants” based on existing human brains. “If there’s a plausible chance that an entity you mistreat might be conscious,” he writes, “the safest moral choice is to assume that it is rather than risk tormenting a sentient being.”

Do androids dream of electric sheep? If they say they do, Kurzweil finds it insulting to suggest otherwise.

The chapters on social and economic disruptions caused by the law of accelerating technological returns are the book’s weakest, and not just because they feel like padding. Kurzweil spends two long chapters summarizing the work of the New Optimist movement, especially that of his friend, the philosopher Steven Pinker. While alive to existential risks, Kurzweil subscribes to Pinker’s view that all the megatrends of the modern era—economic growth, literacy, lifespans—have been and will continue to be largely positive. Supercharged by ever-improving AI, Kurzweil’s version of New Optimism is one of blinding progress, forever. Nanorobots will repair our genes and enable us to achieve “longevity escape velocity.” Three-dimensional printing will dematerialize manufacturing. Miniaturized solar cells will replace fossil fuels. Biocomputers will reduce the energy needed to power an infinitely expanding computational churn, allowing us to beat a hasty AI-powered retreat from the brinks of runaway climate change and ecosystem collapse.

On this last point, the law of accelerating returns is in a race with entropy, and it had better start delivering the promised salvation soon. All this computation is expected to consume one-fifth of the world’s electricity by 2026, part of an overall megatrend of material and energy intensification, not reduction. In The Dark Cloud, French journalist Guillaume Pitron notes that in the 1960s, an analog telephone was built with 10 common elements, while modern cell phones require rare earths as part of a mix comprising more than 50. Powering the steep slope to the Singularity will require technologies that do not yet exist, and must be implemented at scale within a decade or so. Kurzweil is characteristically relaxed—or perhaps arrogantly overconfident—in his faith that collapsing ecosystems and resource wars will disappear into the rearview of the Singularity by midcentury. “Once humanity has extremely cheap energy (largely from solar and, eventually, fusion) and AI robotics, many kinds of goods will be so easy to reproduce that the notion of people committing violence over them will seem just as silly as fighting over a PDF seems today,” he writes.

Even by his own timetable, this leaves another 20 years to contend with various social pains, dislocations, and inequalities wrought by technological progress approaching warp speed. These will be temporary, says Kurzweil, because the arc of the technological universe bends democratic—just look at the smartphone—and will bless our enhanced descendants with novel and magnificent forms of work, communication, art, and leisure. Kurzweil sees hints of this near future in the app-based economy of recent decades. Has technology destroyed industries that once provided stable income and benefits to millions of people? Yes, but the gig economy “allows people more flexibility, autonomy, and leisure time than their previous options.” Are humans near the end of their biological lifespans breaking their knees working double shifts in Amazon warehouses? Yes, but for many, working at later ages “is an enjoyable source of purpose and satisfaction.” He calls a half-century of growing inequality and stagnant wages a “misleading” perception, one that overlooks the “enormous value” people place in social media. The Singularity will absolve us; meantime, let them eat TikTok.

The Silicon Valley–scented anti-politics that pervades The Singularity Is Nearer reflects a general lack of suspicion around the motivations and intentions of state and corporate actors. That the wealthy states and individuals funding the replication of human brains might also want to replicate and entrench their own power—deploying exponential rates of technological advance to achieve an exponential expansion of social control—does not much concern him. He expresses only disappointment, for example, that Meta halted “exciting progress” toward an AI-powered “brain wave–language translator” whose proto-type enabled the company to predict with 97 percent accuracy what words users were thinking.

Kurzweil’s trust extends to the AI research labs overseen by the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. During a combative interview last March, Joe Rogan challenged Kurzweil on his sanguinity about the potential for an AI-powered surveillance state, and more generally about the motives of concentrated power. As Kurzweil muttered about “imperfections in the way phones are created,” it wasn’t clear what surprised him more—Big Tech and the state colluding to surveil the public, or that anyone would care about such trifles on the cusp of superintelligence and endless life.

Futurists can sound like starry-eyed boosters, but they are primarily messengers. The most challenging of them are active inventors like Kurzweil and James Lovelock, who wrote a book advocating a version of the Singularity shortly before his death in 2022 at the age of 103. When Arthur C. Clarke told the BBC in 1964 that soon “men will no longer commute, they will communicate,” he spoke as the author of seminal papers on fixed-orbit satellites. Kurzweil has always operated in the same dual mode, urging us to prepare for the epochal changes he has seen from his motherboarded mountaintop, which can be neither slowed nor stopped. Whatever one thinks about the likelihood or merits of the Singularity, many of his long-range claims related to compounding computing power have landed on dimes.

While finishing The Singularity Is Nearer in 2023, he wrote that any book written on the slope of an exponential curve will be outdated by the time of publication. Indeed, the week the first copies shipped, the Swiss startup FinalSpark offered commercial access to its biocomputing service, Neuroplatform, which uses an electrode-based reward system to teach tiny orbs of human brain tissue known as “organoids” to perform large-scale computation while using a fraction of the energy that computers do. The innovation, in parallel with ongoing breakthroughs in microcapacitors and the grafting of human gray matter onto silicon chips, conforms to Kurzweil’s prediction that biocomputing will soon match extreme power with extreme efficiency.

The book’s discussion of AlphaFold, a biology prediction tool created by Alphabet’s DeepMind division in 2018, was also outstripped by events. In May, the company released an updated version that produces dynamic models of millions of DNA and RNA molecules. Understanding how these proteins fold brings medicine closer to preventing degenerative diseases. It also chimes with Kurzweil’s prediction that we will begin to reach “longevity escape velocity” this decade—adding more than a year of life for every year lost.

When it comes to this front of the Singularity, the exponential curve of medical advance, Kurzweil likes to needle defenders of sickness and death using a transhumanist version of the atheist and the foxhole. When the chips are down, and if given an option, he maintains that the vast majority of people not in excruciating pain prefer life. “Why,” he asks, “would anyone ever choose to die?” Unlike the nature of consciousness, this is an evincible proposition, an aspect of the Singularity that I suspect many of Kurzweil’s bitterest critics would be pleased, if only secretly, to test.

*This article has been updated.