When the sociologist Arlie Hochschild observed a set of couples for her book The Second Shift: Working Families and the Revolution at Home, she tried to make her presence “as unobtrusive as a family dog.” She mostly sat in the living room observing how they ran their households—who gave the kids the bath, who made dinner or did the laundry—and then compared her assessments with how the spouses themselves described their workload. The accumulated details of her observations—the way Evan putters around with his tools in the evening while Nancy does bedtime, dishes, and laundry, or how Peter claims to not help around the house out of fear Nina won’t respect him—stack up to a pile of blame, laid at the feet of often alarmingly useless husbands. One gets the sense that Hochschild sometimes wishes she could jump up and bite some of her subjects.

In Holding It Together: How Women Became America’s Social Safety Net, the sociologist Jessica Calarco takes the baton from Hochschild. Through in-depth, qualitative research with families from across the socioeconomic spectrum, most of them in Indiana, combined with insights from large-scale surveys, Calarco arrives at a different damning conclusion. Thirty-five years on from The Second Shift, it’s clear that the problem women face is larger and more amorphous than the stubborn asymmetry of straight marriages. The problem, according to Calarco, is that women have come to stand in for America’s social safety net in its entirety.

The Second Shift was first published in 1989, the era that birthed the image of the coiffed career woman holding a briefcase in one hand and a baby in the other. Hochschild’s 10 representative families from the Bay Area illustrate a range of what she calls the “gender strategies” of each spouse, how they align their own visions of gender roles (traditional, transitional, egalitarian) with the professional and marital opportunities available to them. But when Hochschild was writing, nearly 85 percent of 35-year-old Americans had married. Today, that share is under two-thirds. Income and wealth inequality have widened, and union membership has plummeted, while the basics of a decent life, such as housing, childcare, and health care, have gotten increasingly expensive. America’s two parties and its citizens are more polarized, and unable to agree on public policy solutions to a crisis of care. Women are often left picking up the slack. These social, economic, and political trends cannot be addressed by men washing a few more dishes.

Holding It Together is among the latest in a stream of books addressing the peculiar ordeal that is American motherhood: nonfiction memoirs-cum-manifestos such as Screaming on the Inside: The Unsustainability of American Motherhood by Jessica Grose, Essential Labor: Mothering as Social Change by Angela Garbes, and This American Ex-Wife: How I Ended My Marriage and Started My Life by Lyz Lenz; novels like Jessamine Chan’s The School for Good Mothers and Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s Fleishman Is in Trouble; and academic books such as Failing Moms: Social Condemnation and Criminalization of Mothers by the sociologist Caitlin Killian. Calarco’s book sits somewhere in between, combining the rigor and depth of formal academic work with journalistic readability.

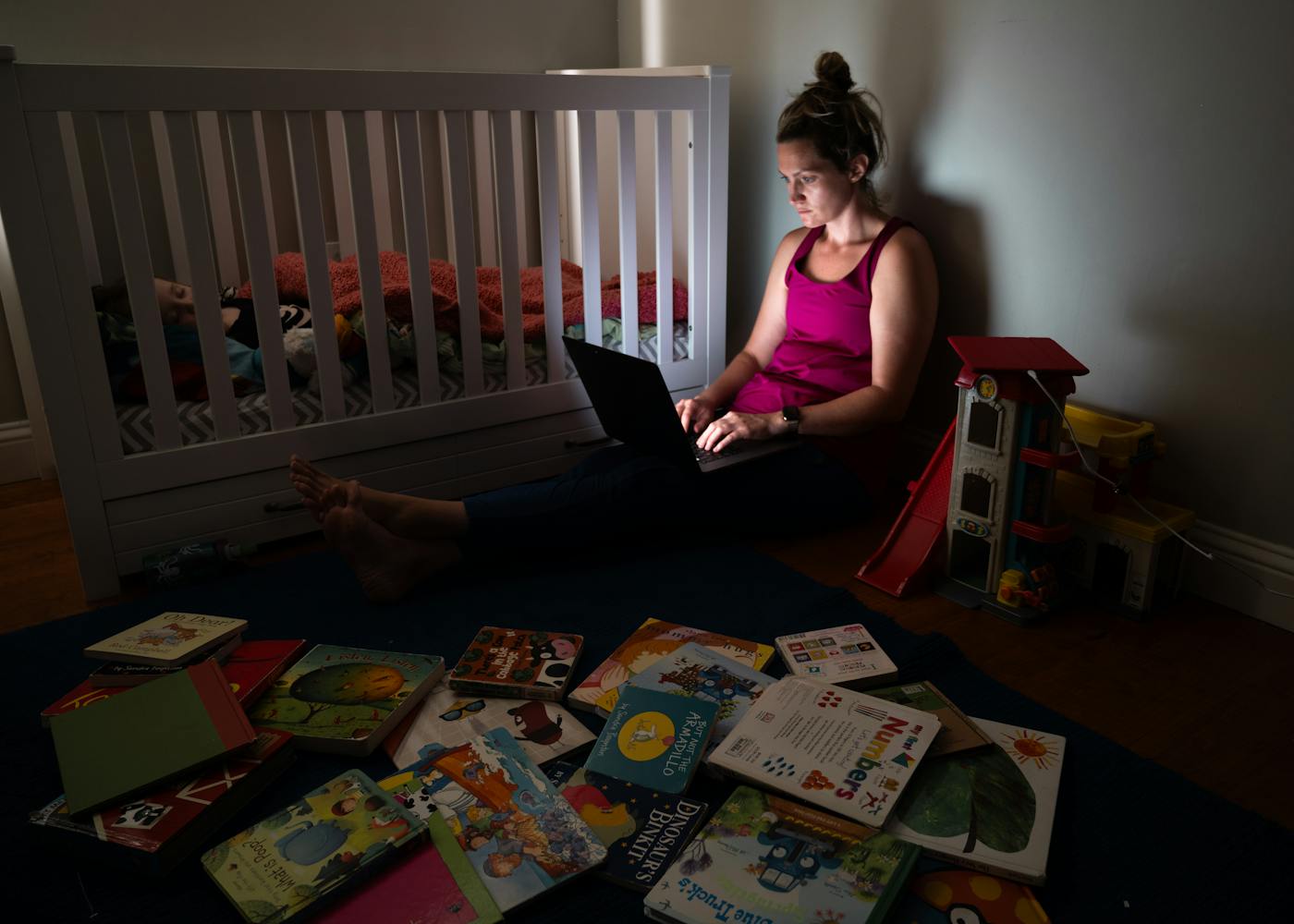

Calarco and her research team interviewed over 250 families between 2018 and 2022, many times “sitting with moms at kitchen tables or on back porches or on the floor in living rooms as kids played nearby,” although the pandemic meant some research had to be done remotely. She also conducted qualitative surveys of her participants, in which she asked questions such as whether they would support a national low-cost childcare program, or if they agreed with statements like, “People who are poor have not worked as hard as most other people.” These were complemented by two national surveys on parenting during the pandemic and attitudes about parenting and social programs. These stories, which make up the heart of the book, paint a devastating portrait of a callous, stingy country held together by duct tape and paper clips. Where other wealthy countries have invested in welfare states that support families and help cushion people when work or life goes off track, the United States has assigned much of that care, responsibility, and mental workload to women.

Calarco begins her story in 1942, when the United States, desperate for workers while men fought abroad, allocated money to childcare through the 1940 Lanham Act, which funded housing and infrastructure in war-related production hubs. The share of women with young children participating in paid labor swiftly rose from one in 30 to one in six. Once the men came home, though, the funding dried up, and women were shooed back into the home. Institutions “from the media to the medical establishment” helped create the idea that women “would have to be ‘crazy’ (or maybe not even ‘real’ women) to want a job when they could stay home,” Calarco recounts.

Meanwhile, throughout the 1930s and 1940s, members of the National Association of Manufacturers, a pro-business lobby, brought over Austrian neoliberal economists to train students at U.S. universities. Star acolytes such as the University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman successfully spread the ideology she calls “the DIY society,” “one where people are expected to solve their own problems, rather than count on the government or even their employers to support them,” and are shamed when they fall short. The 1980s and 1990s reinforced this combination of family values and neoliberalism in rhetoric and policy, even as Americans got divorced at some of the highest rates in the world. The result is a country that, in word and in deed, offers individuals and families little except blame as they struggle to survive.

Yet something, ostensibly, is keeping this nation from going utterly to shreds. The duct tape and paper clips keeping our society intact have a gender. This fragile arrangement, in which Americans somehow stay afloat with a fraction of the government support provided to citizens of other rich countries, relies on what Calarco calls “the magic of women.” Why women? In Calarco’s telling, “we groom girls to stand in for the social safety net from the time they’re old enough to hold a baby doll,” socializing them to assume they’re natural caregivers, and training them to be what the sociologist Miranda Waggoner called “mothers-in-waiting.” This is perhaps more likely to be the case in Indiana, where Calarco and her team did the majority of their research, and which skews more conservative and Christian. In other parts of the country and other cultural milieux, motherhood has become far less compulsory, as Anastasia Berg and Rachel Wiseman found in interviews and surveys with over 300 women for their recent book, What Are Children For? Regardless of whether women buy into the ideology, they are the default caregivers. In one of the national surveys Calarco conducted, 84 percent of moms in mom-dad families reported they are primarily responsible for caring for a child who got sick or, during the pandemic, had to quarantine. This was the case even for 77 percent of the moms who said they were the primary breadwinners in their households.

Calarco’s first example in the chapter on how girls become “mothers-in-waiting” is Brooke, who grew up in a conservative evangelical family yet “never wanted to be a mother.” But after getting pregnant in college, she ultimately decided against an abortion after seeing the fetus’s heartbeat on an ultrasound. (The rise of mandatory ultrasounds and abortion bans in many U.S. states now effectively trap women into motherhood, Calarco argues.) The many tentacles of the DIY society quickly begin snaking around Brooke’s life, crushing her dream of finishing college and getting a nursing job, where she could earn $75,000 a year or more. Her parents both work in low-wage jobs, and the family can’t afford childcare for her son, Carter, so she has to drop out of school. She won’t leave him with her parents to take night classes, because she worries they will spank him. She eventually gets a job at the retailer where her mom works, but “absolutely hated it.” When the director of her son’s day care center offers her a minimum-wage job that also saves her the cost of his care, she winds up falling in love with the work. But just as things pick up, with a promotion to assistant director and a raise to $25,000 a year, her higher income renders her ineligible for some of the meager government support she’s been receiving. When her story ends, she has remarried an auto mechanic, had a second child, and continues to work at the childcare center, her dream of a nursing degree conspicuously unrealized.

Another story shows how one need not be a mother at all to get saddled with a caregiving load heavy enough to sink any prospect of upward mobility. Sylvia was only about 15 when her older brother Dustin; his girlfriend, Destiny; and their infant daughter, Maizie, moved back into his mother’s home. Sylvia and Dustin’s mother supported the entire household by holding multiple jobs as a home health aide, gigs that came with no benefits and (you guessed it) low wages, so Sylvia cared for baby Maizie after high school and most evenings, too. Dustin vanished for days at a time because of an opioid addiction, and after Destiny had a second child, Onyx, she moved out with both children. But her severe postpartum illness led her to use drugs as well; she also, according to Sylvia, threatened to kill her children, in what was likely an episode of postpartum psychosis. Instead of connecting Destiny to mental health care and substance abuse treatment, Indiana’s Department of Children’s Services removed both kids from her home and placed them with Dustin, who was rarely home. Sylvia, still in high school, became the primary parent to her niece and nephew.

Destiny finally got her kids back after two years of struggling with her addiction and the state. Fearing further interference from DCS, she asked Sylvia, who had hoped to go to college, to informally take partial custody. Maizie, Onyx, and Sylvia all lived with Sylvia’s mother, and Destiny and Sylvia co-parented, splitting the $200 a week for their childcare. Both women took jobs as home health aides, “a job Sylvia hated.” But Destiny never quite made it out of addiction—“never got the help she really needed,” Calarco notes, and was last known to be dating a truck driver and living with him for weeks at a time on the road. Nor did Dustin ever grow into a reliable parent. Today, Sylvia doesn’t even know where he lives. Even after she married and had a daughter of her own, Sylvia still cared for Maizie and Onyx, who lived with her full-time.

Brooke, Sylvia, and their family members are all white. Black women are often tasked with doing even more with even less. They earn 79 cents for every dollar earned by white women, even though they work more hours. They are 47.5 percent less likely to be married, and Black mothers are 67.5 percent of the primary breadwinners in their households, a mirror image of the situation for white mothers, of whom just 37 percent earn more than their husbands. Historically, Black women had long played “the dominant role in family and marriage relations,” as the Black sociologist E. Franklin Frazier observed. Yet for being both breadwinners and caregivers, they earned not gratitude but opprobrium, blamed for the Black family’s “tangle of pathology,” in Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s memorably insulting phrase.

When Calarco introduces Patricia, who is Black, it is 2020 and she is living with her husband, Rodney, a construction worker who is also Black, and their three kids in Indianapolis. Their combined $28,000 household income made them eligible for some basic government support, such as childcare subsidies, food stamps, and Medicaid. But the help wasn’t enough, and Patricia often found herself at the local food pantry at the end of the month. She worked from home in customer service in order to be present for her children before and after school, or in case one was sick. Although it was “the best work-from-home job she could find,” she found it “repetitive and demoralizing.” When Covid hit, Patricia and Rodney “never even talked about who would care for the kids.” Rodney kept going to work every day, while Patricia was home with three children who constantly needed her and interrupted her throughout her workday. She became impatient and overwhelmed, suffering from headaches and deep maternal guilt. To cope, she cut back her workweek to four days, hoping that extra day would allow her to focus on her children. In early 2021, she found out she was pregnant with twins. Patricia decided to keep the four-day schedule so she could take care of household chores such as groceries and laundry on her day off.

But there were other people who needed her. Patricia, Calarco notes, “is one of the only people in her family with a reliable vehicle” in a city recognized in 2019 for having the worst public transport system in the United States. She became “her family’s chauffeur,” taking them to the grocery store or doctor’s appointments to spare them hour-long commutes by bus. Her mother and sister relied on her for emotional support, too, and she had trouble setting boundaries so she could have time for herself. She was aware, too, that she had often relied on others’ support in the past, and might one day have to do so again. Just before the twins were born, she and Rodney divorced. They had often fought over Rodney’s inadequate help with chores and the kids, and his “refusal to wear a mask or take other precautions to keep the family safe” during Covid was finally too much for Patricia. Her friends and family stepped up, but Patricia was doing the near impossible: looking after five children in a two-bedroom apartment, holding down her job, and covering Rodney’s car payments so he could make the drive to see the kids. “I was depressed on how I was going to keep my job and still trying to manage the needs of my twins. It was a struggle trying to answer calls and type and try to burp a baby and feed a baby and change a baby,” she said. “And oh, two babies have had a blowout at the same time—that just about had my hair out.” She uses her meager downtime to tidy her home, because the clutter brings on depression.

A common thread runs through these stories: aspirations and hopes crushed by caregiving responsibilities, low-wage jobs, lack of or inadequate government support, and men unwilling or unable to help. The historian Laura Briggs has observed that in 1997, the year when President Bill Clinton’s welfare reform policies went into effect requiring recipients to work, Walmart became the nation’s largest employer, with a 75 percent female workforce. (Briggs also observes the irony that low-wage employers such as Walmart encourage their employees to apply for government benefits, which are necessary to subsidize a minimum wage that rarely approaches a living wage.) Today, one of the fastest-growing jobs is home health aide, another poorly paid caregiving profession staffed almost entirely by women, some of whom, like Sylvia, would rather be doing a different job.

It’s easy to assume while reading accounts like Calarco’s that these are simply the unavoidable burdens of parenthood, and to forget how different motherhood can be—and is, in other countries. In the afterword to a 2012 edition of The Second Shift, Hochschild zooms out from America’s kitchen tables and living rooms, and looks across the Atlantic to Norway. Thanks to Norway’s 35-hour workweek, 11-month paid parental leave, and use-it-or-lose-it month of paid paternity leave, she writes, Norway “has undergone a gender revolution, but avoided a stalled revolution.”

I have been to Norway and observed parenting there. It is awesome. My best friend is Norwegian; she sent her three kids to day care full-time in Oslo for less than what I pay to send my daughter for just two days a week in New York. Dads are more present and engaged. These kinds of supports—not to mention the postpartum home visits from nurses, the statutory right to paid leave for a sick child, the public health care system—take a great deal of the structural stress out of parenting in Norway, leaving mostly the idiosyncratic stress peculiar to the foibles of each parent and child.

Calarco also casts her eye to the Nordic countries. Toward the book’s end, she recounts Iceland’s first women’s “day off” in 1975, when women across the country simply walked off the job (whether that job was in a bank, a school, or at home) and took to the streets. In 1980, Iceland and the United States had equal scores on the United Nations’ Human Development Index, 0.57 out of 1.0. Thanks to policy changes in the intervening years (including many put into place by the country’s female president, elected in 1980), Iceland’s score rose to 0.96, while the United States is stuck at 0.78.

Americans who oppose expanding the safety net often quibble that Nordic countries are small and homogeneous, but it is not obligatory to care less for one’s fellow citizens as population size grows or because they look different. Furthermore, the United States is the fourteenth-richest country in the world, behind Norway and a number of tax havens such as Monaco and the Isle of Man, but ahead of Denmark, Iceland, and Sweden. And the United States has extended the social safety net before—through the New Deal during the Depression, the Lanham Act during World War II, and more recently in the pandemic, when the government sent out stimulus checks, helped more people get on Medicaid, and expanded a tax credit for low-income working families. It is not a question of whether a safety net is possible, but of how those in power have been able to withhold it for so long from citizens who plainly need it.

The instinct to shovel responsibility onto women runs so deep that even buckets of free federal stimulus money can’t persuade some lawmakers to lighten women’s load. In 2021, as mothers across the country were at their wit’s end, Idaho Republican state Representative Charlie Shepherd helped vote down a bill that would have directed a $6 million federal grant toward improving the state’s early childhood programs, saying he opposed “any bill that makes it easier or more convenient for mothers to come out of the home and let others raise their child.” By contrast, in a commentary on his country’s family policies, Norway’s former finance minister noted that Norway’s above-average female labor force participation was worth as much to the country as the total value of its petroleum assets. In other words, even on a simple economic basis, women were valuable to Norway, and had been since at least the 1890s, when Statistics Norway began compiling estimates of unpaid household work.

Our miserly social spending is even more maddening when one considers the impossible math of a small day care center. Holly and her wife, Kathleen, struggled with their day care center’s limited hours after it reopened following a Covid-19 closure. Staffing shortages compelled the director to abbreviate the day, from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., and hire fewer experienced workers. “To keep costs low enough for families like Holly’s to afford,” Calarco writes, “the center could only hire staff who were willing to work for low wages and without benefits like health insurance or paid leave.” Holly comes to see how she and Kathleen are “complicit in this thing where it’s like, ‘Oh, we have all these women of color watching our kids and we’re not really taking good care of them.’”

I don’t know the math of the day care center that my daughter attends two days a week, but I know that, at $1,585 per month for those two days, it’s already at the outer limits of what I can afford. Until recently, another woman—my daughter’s grandmother—was my social safety net, watching her for two additional days a week. Then, as the deadline for this review approached, she fell ill with bacterial pneumonia, which likely developed from a virus my daughter picked up in day care. Her doctors at the Center on Aging at Weill Cornell Medicine told her this is increasingly common: Growing numbers of grandparents are helping out, because childcare in New York City is so unaffordable, but then, with immune systems made more vulnerable by age, they get flattened by day care bugs. I’m likely going to rely on another woman—a friend’s teenage daughter—for a few hours each week of additional care.

Other countries have found a simpler solution: Tax people and corporations, and spend that money on public services that benefit everyone. In Norway, both childcare and eldercare are publicly subsidized, which allows care workers, who are mostly female, to earn a living wage ($40,000 annually for childcare workers) and access all the same benefits as any other citizen—heavily-subsidized childcare for their own kids, retirement pensions, and paid vacation days, among other things. A safety net like this won’t fray on account of a bacterial infection; it doesn’t rely on men doing more housework or childcare. It’s a safety net built for women, not constructed of women.