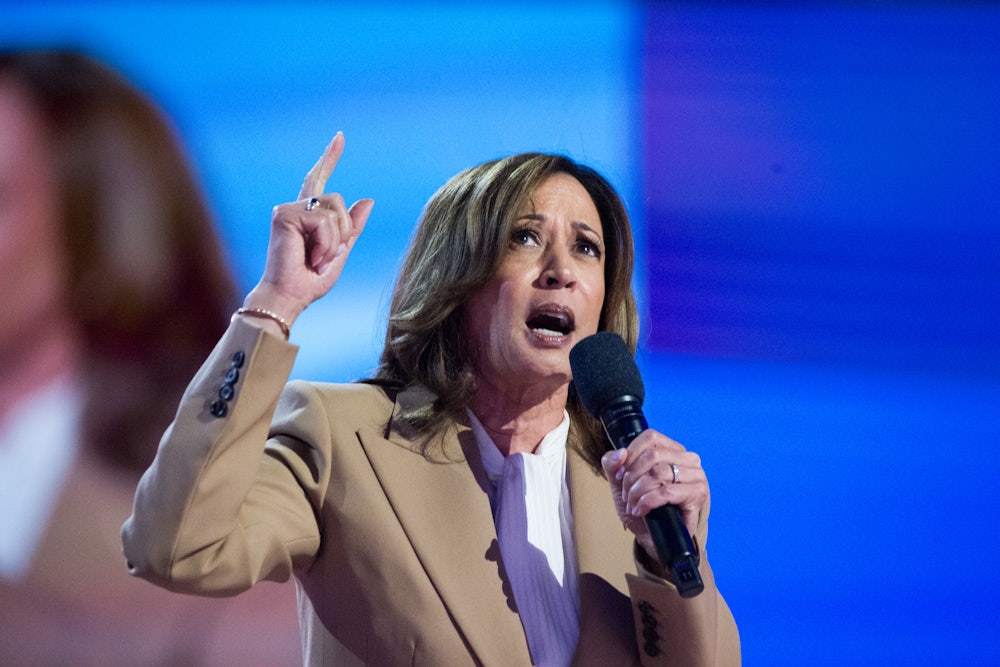

Kamala Harris has made tackling corporate price gouging and raising taxes on corporations and the wealthy cornerstones of her economic platform. She seems to be leaning into some of the Biden administration’s more populist talking points about making life more affordable for ordinary people—earning her plaudits from progressives and predictable freak-outs from Republicans, editorial boards, and economists both on the right and in the discipline’s still mostly orthodox mainstream. So far, however, the Harris campaign hasn’t extended that clear-eyed populism to its climate politics.

Consider the Democratic Party platform for 2024: “To lower prices, Democrats will also keep working to boost supply, fix supply chains and promote competition, especially for essential items like gas and groceries that families depend on,” the party document promises, while boasting that the Biden administration oversaw record levels of oil and gas production. Other parts of the platform talk enthusiastically about “reducing Big Oil’s hold on our economy,” and ding Trump for being beholden to fossil fuel executives.

That’s a pretty wonky jumble of contradictions. And it echoes the Biden White House’s disjointed approach to energy: boosting renewables as the industry of the future, accosting Big Oil for price gouging, then bragging about how much oil and gas they’re producing. The core of the administration’s economic pitch for climate action—reflected in the Inflation Reduction Act, perhaps its signature legislative accomplishment—has been that investing in the energy transition will revive American manufacturing and create millions of jobs. Following suit, green groups backing Harris have launched a $55 million ad campaign across several swing states, aiming to sell the administration’s climate measures to voters on their economic (rather than environmental) benefits. Insofar as this administration has explicitly challenged Big Oil it’s generally for price gouging—not polluting, or having spent decades stalling progress to reduce emissions.

It’s easy to understand how the Biden administration, and by extension the Harris campaign, got into this bind: There’s a defensible case to be made for focusing on the positive aspects of climate action rather than on cutting fossil fuels, and for touting the Biden-Harris administration’s real-world achievements. Yet applying the same talking points that work for grocery prices to prices at the pump has left Democrats ostensibly committed to reducing emissions in an awkward spot: essentially, arguing for unlimited and ever-expanding fossil fuel production. Gas and groceries—paired under the same heading in the platform—are alike insofar as they are things that most people need to buy regularly. But they’re sold by very different industries, and applying the same talking points to both doesn’t work very well.

There’s an alternative available: pointing out how much of a scam the fossil fuel economy is, and the mounting, everyday costs of the climate crisis it’s exacerbating. If the Harris campaign and Democrats more broadly are serious about winning elections and building support for climate policy in the future, they should start crafting a more coherent way to marry the party’s embrace of economic populism with its professed commitments to decarbonization.

First, let’s review why politicians’ promises to lower oil and gas prices are even more nonsensical than they might seem. Needless to say, the U.S. government does not control oil production. Decisions about fossil fuel production, distribution, and pricing in the U.S. are virtually all made by the companies that drill, refine, and sell it. So when the Democratic party says it will work to “boost supply,” what it’s really talking about are additional policies to incentivize that industry into producing more oil; Biden’s favorite tool toward that end has been the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, or SPR, i.e., selling oil from our national stockpile to modestly offset higher market prices, then buying fuel from the industry when it gets cheap enough. For a sense of scale, the U.S. consumes roughly 20 million barrels of petroleum per day and currently makes about 13 million barrels per day. The total authorized storage capacity of the SPR is 714 million barrels. It’s big, but not that big.

Because much of U.S. oil production now happens via more expensive, unconventional extraction methods, including fracking, companies here prefer oil prices to be relatively high so that they “break even” or (ideally) profit. By positioning the U.S. government as a guaranteed buyer of cheaper oil, pledges to refill the SPR amount to setting a price floor—in essence, promising companies they won’t have to sell their products too cheaply. Inducements to “boost supply” of gasoline, that is, often function as guarantees to raise prices. These promises contradict the administration’s other goals, as well. While elsewhere in their platform Democrats state their commitment to “eliminating tens of billions of dollars in subsidies for oil and gas companies,” their efforts to keep gas prices low could entail the opposite of that. There are also very few guardrails in place to prevent companies from overinvesting in fossil fuel infrastructure that could stay online for decades, or to safely shut it down once it’s no longer needed.

The relationship between boosting domestic production and bringing down prices at the pump likewise isn’t an especially direct one. Much of the crude oil produced in the U.S. is refined abroad. Oil is also a globally traded commodity. If members of the Organizations of Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC, decided to pump like gangbusters—flooding the world with excess supply—then there’s not much the U.S. could do to prevent oil prices from crashing. Sparsely regulated, little-known trading firms have enormous leeway to shape prices as they ferry it between buyers in different countries, as well.

Trying to ease pressure on consumers by backing unchecked domestic production, in short, doesn’t make much sense. It won’t guarantee relief and threatens to lock in decades of excess emissions, and hand even more giveaways to an industry that’s poured its fortunes into the Republican Party’s attempts to block anything called climate action.

But that’s not to say there’s nothing the U.S. can do. Throughout much of the twentieth century, the U.S. enforced strategic price controls on fuel, for example rationing gasoline to conserve rubber during World War II or enforcing controls to allay fears about running out of gas during the Nixon administration. It was Democrat Jimmy Carter who opted to let price controls expire in the late 1970s, one of many decisions that helped to spike the cost of living during his administration and hand the election to Ronald Reagan.

The Harris campaign so far hasn’t articulated a compelling story about climate policy, which accordingly hasn’t come up much this week at the DNC. Just pointing to the Inflation Reduction Act’s achievements isn’t a solution: It’s still not clear how much they’re resonating with voters.

The answer may well be to start talking about climate change as a kitchen-table economic issue in its own right. Stories about how the fossil fuel economy is screwing people over are easy to find. As I wrote recently, homeowners in Florida are paying roughly five times the national average for home insurance. Working- and middle-class people from California to Oklahoma are struggling to afford mortgage and rent payments as insurers pass their costs onto their customers. Ratepayers are spending more and more of their paychecks on electric bills made higher by needing to pump air conditioners during heat waves. They can thank their utilities for lobbying to pass the costs of expensive, unnecessary new fossil-fueled power plants onto them. Poorer renters, especially, risk baking in their homes. Workers are dying on the job of heat exhaustion.

The Beltway consensus of the past two decades is that Democrats have to play defense on climate policy, focusing on the benefits of clean energy while quietly conceding to Republican claims about the need for a still largely fossil-fueled “energy independence.” Candidates willing to buck that trend have any number of tools at their disposal to build a more populist climate platform. In addition to drawing on the country’s rich, successful history of using price controls to combat gas price volatility, investments in housing, mass transit, and electric vehicles can help make the U.S. a less car- and gas-dependent place overall, insulating consumers from prices at the pump. Instead of blaming Big Oil for price gouging, Harris can offer rapid progress toward real energy independence: freedom from fossil-fueled volatility and an energy system controlled by a handful of reactionary billionaires. The costs of climate change are already piling up on monthly bills, and there are plenty of greedy corporations plotting to keep profiting off of it.