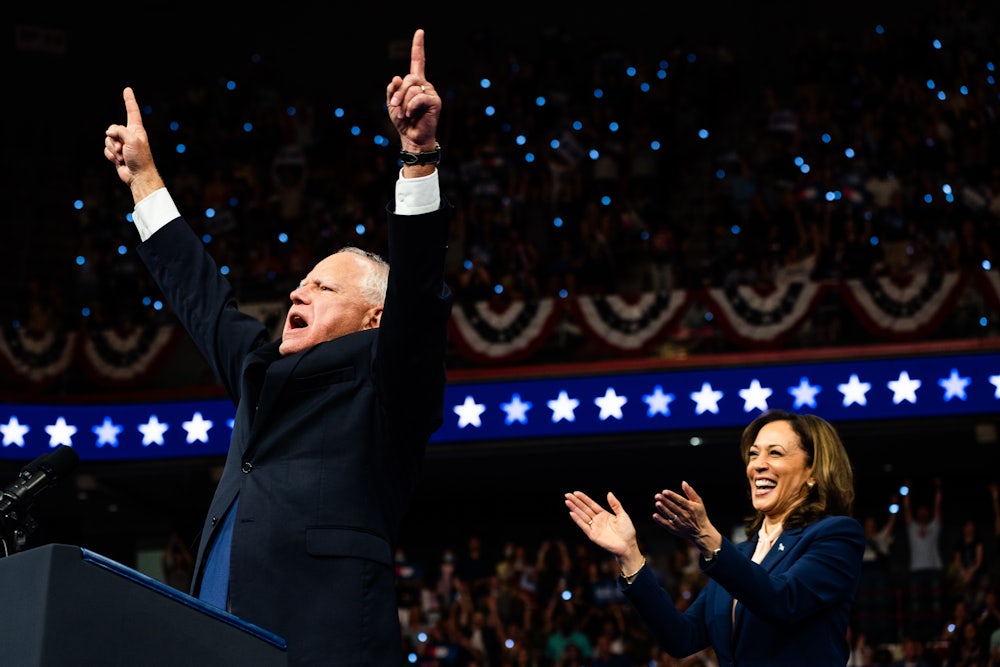

A lot has already been said about Governor Tim Walz’s folksy demeanor, as well as his record when it comes to labor, universal school lunches, voting rights, and generally not being “weird,” the moniker he has stuck on the GOP ticket that became an immediate Democratic rallying cry.

But Walz specifically, and more importantly the Minnesota Democratic Party generally (known in-state as the DFL, for Democratic-Farmer-Labor), has provided an important political lesson: Governing, getting results, and challenging corporate power after winning elections begets success. Their accomplishments, and how they led to Walz joining the Kamala Harris ticket, is a direct rebuke to the triangulating nonsense and constant fear of right-wing attacks that still dominate too many Democratic circles.

“Right now, Minnesota is showing the country you don’t win elections to bank political capital—you win elections to burn political capital and improve lives,” Walz said in early 2023. Indeed, after unexpectedly winning full control of the state legislature in 2022, Minnesota Democrats went on an absolute policymaking spree, passing a major voting rights package, a major labor law reform, paid family and medical leave, universal school meals, a mandate that electricity be carbon-free by 2040, and a reproductive rights guarantee. That record was reportedly one of the things that drew Harris to Walz over some of the other, higher-profile candidates.

Embedded in much of this legislating was a willingness—an eagerness, even—to directly challenge entrenched corporate power. Minnesota Democrats approved, and Walz signed, a ban on noncompete agreements, for example, eliminating an abusive contract corporations use to lock workers into their jobs and lower wages. He also signed an economy-wide ban on junk fees, eliminating the obnoxious and anticompetitive charges levied on everything from live events tickets to hotel rooms to rental housing.

Add to that the nation’s most extensive right to repair law, giving consumers the ability to fix their own consumer electronics, as well as a new law to rein in hospital consolidation that kiboshed what would have been a hugely destructive merger between a Minneapolis hospital and a South Dakota–based health care conglomerate, and you have a meaningful and broad blow against the corporate consolidation that has allowed megabusiness to dominate local economies over the last several decades.

Minnesota Democrats did all this with just a one-seat majority in the state Senate, putting to shame other supposedly blue states where Democratic supermajorities don’t have a list of accomplishments a third as long. It’s no coincidence that several of those policy items—such as the noncompete ban and the elimination of junk fees—mirror some of the most popular efforts of the Biden administration, which has more aggressively attacked corporate power than any other president’s over the last half-century.

In my experience pushing for state-level, anti-monopoly policies over the last four years, these are the sorts of things that move people and votes. Over the last 20 years or so, 75 percent of U.S. industries have grown more consolidated, leading to a range of downstream harms, including lower wages, lower rates of small business creation, and the outsourcing and eroding of the U.S. manufacturing base as CEOs sought to financialize rather than build. Voters across the country, in areas red, blue, and everything in between, get that this has occurred and understand its consequences. They know Amazon warehouse jobs are dangerous, that corporate landlords are taking advantage of them, and that pricing tricks and games are unfair, and they’re willing to vote accordingly.

Minnesota Democrats understand this dynamic and have made a big bet that aggressively addressing it will pay off politically not only over the next few months or for the next few news cycles, but over the long haul. While in Congress before becoming governor, Walz displayed some similar tendencies, voting against the 2008 bank bailouts and against fast-track approval for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which had become a national lead weight around Democrats’ ankles. Such positions helped him consistently win a Republican-leaning district, even in 2016 when Trump dominated among the same set of voters.

Which is not to say he doesn’t have blemishes when it comes to corporate power and governance. He vetoed a bill that would have set minimum labor standards for rideshare drivers (though a compromise measure later won at least grudging approval in the state), for instance, and he helped the Mayo Clinic—a major health care industry player—block a bill that would have created a board to set working standards for nurses.

It’s also an open question how much he would have focused on challenging entrenched power absent the statehouse DFLers who pushed bills through the legislature and campaigned on corporate consolidation and control issues. While key members of the Minnesota legislature, such as state Representative Emma Greenman and state Senator Lindsey Port, as well as Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison, were openly promoting an anti-monopoly agenda, Walz was not.

What he did do was recognize those issues’ political salience once ideas and theories become viable laws and act accordingly. When push came to shove, he generally allowed himself to be pushed in the direction the populists and anti-monopolists, and ultimately the voters, wanted to go.

This is key because, with Harris’s own mixed record on issues of corporate power and consolidation, there’s certainly the potential for the campaign to fall back on the triangulating faux-centrism that doomed candidates such as Hillary Clinton or the famous Democratic Blue Dogs, or to embrace the Democratic billionaire-led push to have Harris publicly abandon the Biden administration’s most effective enforcers and regulators.

Doing so would be a mistake, because it turns out that burning political capital to challenge entrenched power is not only effective but appealing to a wide swathe of the public, and hopefully adding Walz to the ticket is a reflection that Harris, and the broader Democratic establishment, understands that reality. Poll after poll shows that the sort of items Walz and the Minnesota Democrats embraced are wildly popular across the political spectrum and across all demographics. They effect real change in workers’ daily lives and in the ways businesses behave, leading to a fairer economy based on the needs of the many, not the profits of the few.

And if Minnesota Democrats are right, that approach will have elevated one of their own to the White House.