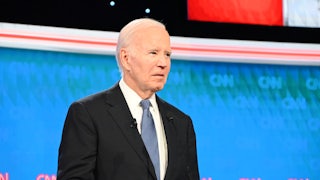

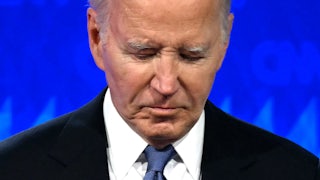

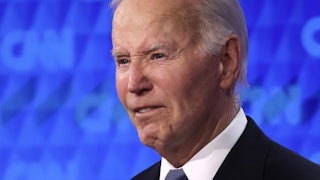

Joe Biden huddled with his family at Camp David Sunday to discuss his political future. We are told, from widely circulated reports, that his decision to stay in the race will come down to what his wife, Jill Biden, says. On Saturday, in a widely circulated report, a source told a team of NBC reporters that “if she decides there will be a change of course, there will be a course.” Then, on Sunday afternoon, The New York Times’ Peter Baker and Katie Rogers reported that Biden’s family “urged him to stay in the race and keep fighting despite last week’s disastrous debate performance.” Well, it sure seems like Jill didn’t decide there should be a change of course.

That, if true, is really a problem. This is not a decision about whether Dad should go ahead and get that triple-bypass surgery. This is a decision about the future of the country and whether it will fall into fascist hands. That isn’t, or at least it shouldn’t be, solely up to the Biden family. There are other people around Biden who have the power to influence him. He calls longtime adviser Mike Donilon several times a day. Ron Klain is out of the White House, but he and Biden are said to have weekly check-ins. (Klain told the Times’ dynamic duo that he is “100 percent certain” that Biden will stay in the race.) And Ted Kaufmann, who’s been Biden’s friend for 50 years, is the person who told Biden in 1987, after he was hit with plagiarism charges, that he needed to end his presidential campaign.

But there’s one other person on the scene whom Biden takes very seriously. And he has an additional power that other Biden insiders don’t have: He and he alone has the moral authority within the Democratic Party to call the difficult shots, map a direction for his party, and get everyone to say OK. That of course is Barack Obama.

Obama made his initial reaction known in a tweet he posted last Friday afternoon that served as a pep talk for panicking Dems:

Bad debate nights happen. Trust me, I know. But this election is still a choice between someone who has fought for ordinary folks his entire life and someone who only cares about himself. Between someone who tells the truth; who knows right from wrong and will give it to the…

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) June 28, 2024

I’m awfully curious about what kinds of conversations he had over the weekend and with whom, and what he really thinks—about whether Biden is still his party’s least-risky choice, and about whether Biden has it in him to be an effective president in 2027, 2028. And if his honest answer to either of those questions is no, then I hope he is thinking about what needs to happen here, and the role he needs to play to make it happen. For now, his public statements suggest that he is trying to be a source of calm, steadying nerves and establishing discipline during what has been the rockiest stretch of Biden’s presidency. But it would be shocking if he wasn’t seriously weighing the risks of the various options the Democrats have in front of them right now.

I’ve been thinking back over these last few days on how we got to this place. I’ve been reading stories like this Ryan Lizza Politico piece from late 2019, when Biden’s people were semi-openly saying that he would serve as a transitional president. He’d beat Donald Trump because, of the 2020 crop, he was best positioned to do so, which turned out to be right; serve one term; and then, in recognition of his advanced years, he’d move on. “If Biden is elected,” a prominent aide told Lizza, “he’s going to be 82 years old in four years, and he won’t be running for reelection.”

Well … that changed. Were they lying? That will be many people’s first thought, but it’s not necessarily so. Maybe that was the plan at the time (at least to aides, if not to Biden himself). But then, stuff happened. A lot of good stuff: Biden had several unexpected legislative successes. He won wide praise for his handling of Russia’s early 2022 invasion of Ukraine. And some bad stuff: Inflation hit. The Afghanistan withdrawal was a fiasco. His numbers cratered. But it was easy enough to convince himself that voters would completely forget Afghanistan by 2024 (they have—so far), that inflation would abate (it has), and that it wouldn’t be such a big electoral issue (it is).

Then the Democrats outperformed expectations in the midterms, and things looked fairly sunny for the moment. It was clear, from the returns, that voters liked Democrats more than Republicans and that they broadly approved of the Biden agenda, even if they were less rosy about the president himself. And as fate would have it, the post-midterm period is when incumbent presidents make their future intentions known, so the speculation was building at precisely the moment when Democrats were feeling overly bullish. Besides, no incumbent president wants to be a one-termer. One-termers are failures.

And, at that point, Biden’s decline wasn’t nearly so apparent, at least to me. I wrote a column in January 2023, during these weeks of speculation, arguing strongly that he should run. Like Biden, that column has aged badly. But the following month, when Biden took that 10-hour train ride across Poland and gave a vigorous speech in Kyiv, I was feeling like I’d made the right call. Remember, the choice has never been between Biden and some clearly excellent and easily attainable alternative; the choice was always what it remains today: Biden or Kamala Harris or a wide-open process that presented the “how do we sidestep Harris?” problem.

The disturbing signs became more frequent, as I recall, in the summer of 2023. On June 1, he fell down at an Air Force Academy graduation ceremony. The next night, he gave an address from the Oval Office, and he looked and sounded old. He’s had decent moments and bad ones since, but the clear picture is that his mental acuity has declined.

Everyone knew this was a problem. But there was no incentive for anyone to do anything about it. No big-state Democratic governor was going to challenge him, and none of his 2020 rivals seemed like credible opponents. It was likely they would lose, and then they’d be poorly positioned (or so such thinking went) for 2028. No single Democratic leader—Chuck Schumer, say—had any incentive to say he shouldn’t run. That could only be done by a chorus of leading voices, all speaking as one. But there was no desire to do that, because that would have constituted creating a crisis where one didn’t exist. Doing so, moreover, would have damaged the party’s ability to govern—something that it has continued to do pretty well over the past year.

Well, since last Thursday, that crisis exists. To deny this is a crisis is absurd. No one can maintain, as Obama did in that tweet, that this was just a case of someone having a bad night. The cognitive decline was obvious. It could be true that Biden can still perform “the job” in the sense of sitting in meetings, having three options presented to him, and choosing the best one. But a big part of the job is public performance and reassurance too. Maybe the polling hasn’t been as bad—yet—as I anticipated. But if Biden loses 3 percent of Democrats and 6 percent of independents—and those are tiny numbers—he’s cooked. That would be a calamity and, given what Trump has told us about his second-term plans, a bigger disaster than Hillary Clinton’s loss in 2016.

We’re already seeing some polls showing Democratic constituencies floating away. And this raises another key point—the gulf in opinion on such matters between party insiders, whose first reflex is always to justify the status quo, and regular, rank-and-file Democrats. I can promise you that if you asked 50 Washington insiders whether Biden should step down and then asked 50 Democrats at the Whole Foods in Madison, Wisconsin, you’d get strikingly different answers.

Again: Sticking with Biden has, until recently, been the least risky of three options: Biden staying in, Harris replacing him, and him being replaced by a non-Harris option. Now it’s just not at all clear that that’s the case. Maybe Harris can energize some younger people. Maybe she can reintroduce herself to the American public in a more compelling way. Maybe, with the right vice president, she can be part of a team that looks like the future.

And, as I wrote last week, maybe an open process and real drama at the convention would be a good thing. Everyone assumes that with Democrats, it would devolve into a food fight. Well, maybe. But maybe not. That depends on someone having and exercising the authority to guide the process and make everyone agree to and play by a certain set of rules. And besides, isn’t a food fight what they’re having now?

And that’s where Obama comes in. He’s the only figure who can unify the party behind a plan of action. He solves the collective action problem, because he gives everyone—Schumer, Hakeem Jeffries, everyone—the excuse to act: “Well, if President Obama is saying it, then I will, too.” If he anoints a nominee, be it Harris or someone else, there will be griping, of course; but I suspect it won’t take long for Democrats to set aside their differences and take on the common cause of stopping Trump. There’ll be a big unity rally in Chicago right after the convention, and people won’t even remember this week of teeth-gnashing.

In other words, this could work out just fine. Better than fine. To all those who say people like me are panicking, I counter that the real panic is in reflexively sticking with a candidate whose shortcomings became so unavoidably obvious last Thursday. A change of course could be just what the Democrats and the country need.

And if Obama really does still think that Biden is the best alternative, he needs to articulate that in a detailed and persuasive way. I don’t know what that argument would be. But the guy talked his way out of a couple pretty big messes in 2008 and got elected comfortably. If he’s going to stick with Biden, he’d better be all in.

Either way, someone has to lead this party right now. And there’s only one person who can do it.