Two years ago, Justice Clarence Thomas led an originalist revolution of sorts to expand the Second Amendment. The 6–3 decision that he authored in New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen set up a narrow history-and-tradition test that invalidated any gun restriction without a “historical analogue.”

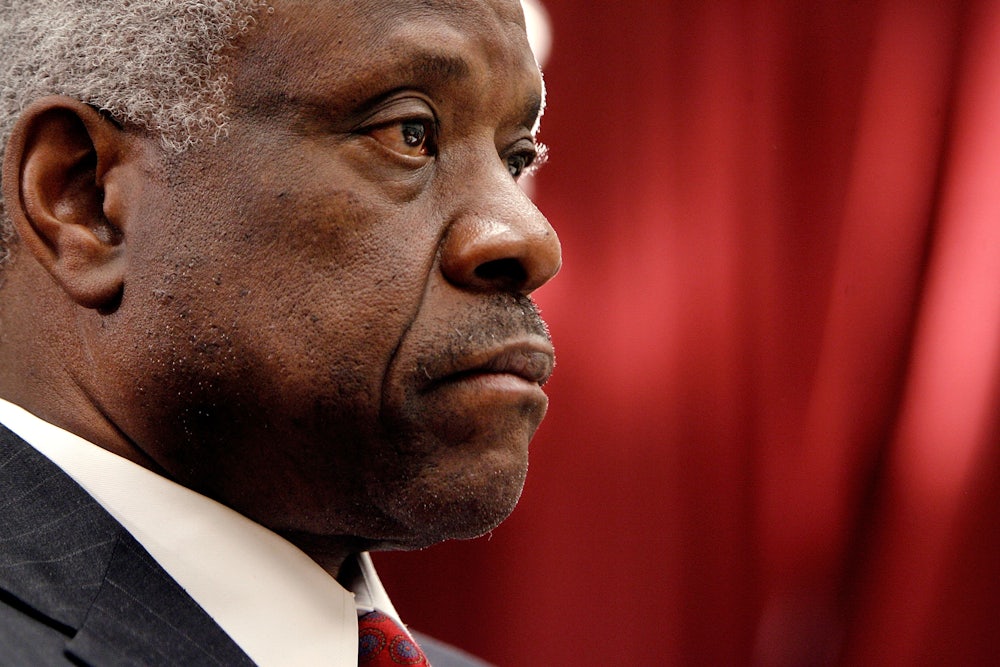

The Supreme Court reversed course on Friday. In an 8–1 decision in United States v. Rahimi, the justices upheld a federal law that temporarily disarms gun owners who are under domestic violence protection orders. This time, Thomas was the sole dissenter in the case. All five of his conservative colleagues in the Bruen majority flipped sides.

“Our tradition of firearm regulation allows the government to disarm individuals who present a credible threat to the physical safety of others,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the court. His 18-page ruling clarified the Bruen test to explain that while courts must still look to founding-era laws for analogues, they need not find a “historical twin” to uphold a modern gun restriction.

Thomas was left to protest the narrowing of his landmark ruling by himself. “After [Bruen], this Court’s directive was clear: A firearm regulation that falls within the Second Amendment’s plain text is unconstitutional unless it is consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation,” he wrote. “Not a single historical regulation justifies the statute at issue. Therefore, I respectfully dissent.”

The ruling has major consequences for gun rights and the Second Amendment. First and foremost, the court shut down the possibility that it would make guns easier to obtain for domestic abusers. Loosening Bruen’s history-and-tradition test also ensures that lower courts will likely find it easier to uphold other restrictions that are currently under scrutiny. Friday’s decision will not restore the pre-Bruen legal landscape, but it is a substantial push in that direction.

Rahimi may also be a watershed moment for the court’s internal dynamics. Periods of Supreme Court history are typically described by the term of the chief justice; we have all lived in the Roberts court era since 2005. For the last few years, the six-justice conservative supermajority led some to describe it as the Thomas court, reflecting his influence as the dean of the court’s conservative wing. With the other justices thoroughly repudiating his hard-line approach to originalism, that brief era may have drawn to a close.

Some Second Amendment cases are about responsible gun owners. Zackey Rahimi is not among them. The defendant in this case has a long track record of misusing guns in public in dangerous ways. Texas police have identified him as the participant in multiple public shooting incidents, including one where he fired at a truck that cut him off in traffic and another where he fired his gun in the air after his friend’s credit card was declined at a fast-food restaurant.

In perhaps the most disturbing incident, Rahimi got lunch with his girlfriend in a parking lot in 2019 and began arguing with her. When he grew angry and she exited the car to leave, he physically dragged her back to the car and shoved her in, striking her head against the dashboard. The incident occurred in broad daylight and in full view of the public.

“When he realized that a bystander was watching the altercation, Rahimi paused to retrieve a gun from under the passenger seat,” Roberts wrote, summarizing the evidence from lower court proceedings. “[His girlfriend] took advantage of the opportunity to escape. Rahimi fired as she fled, although it is unclear whether he was aiming at [her] or the witness. Rahimi later called [her] and warned that he would shoot her if she reported the incident.”

Shortly thereafter, Rahimi’s girlfriend applied for a restraining order against him. The court granted the order after finding that he was likely to commit domestic violence again and that he posed a threat to others. Rahimi soon violated it by stalking her, and when police arrested him for the other gun-related incidents, they found a copy of the order alongside guns and ammunition in his home. Federal prosecutors charged him under a provision known as Section 922(g)(8), which forbids possession of a firearm while subject to a domestic violence restraining order.

A few weeks later, the Supreme Court handed down its ruling in Bruen. The case challenged New York’s concealed-carry permit regime and gave the court an opportunity to lay out a test for lower courts to use when weighing the constitutionality of gun restrictions. Thomas, writing for the conservative supermajority, rejected the balancing tests that most courts had used and instead embraced a maximalist test rooted in originalist principles.

“When the Second Amendment’s plain text covers an individual’s conduct, the Constitution presumptively protects that conduct,” he wrote. “The government must then justify its regulation by demonstrating that it is consistent with the nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation. Only then may a court conclude that the individual’s conduct falls outside the Second Amendment’s unqualified command.”

Gun restrictions could survive, Thomas explained, only if the government could identify a “historical analogue” for them from the founding era. This raised more questions than it answered. What counts as a “historical analogue”? How similar does a founding-era law need to be? How does one determine what falls within the nation’s “historical tradition” of regulating guns? How specific or generalized should judges be when weighing these questions?

Lower courts have struggled mightily to find answers to those questions consistently or coherently. Some federal courts ruled that Bruen had invalidated laws that forbade gun ownership by people with felony convictions and people who used controlled substances because no similar measures existed in the founding era. The “historical analogue” search took strange turns. In one case, a federal judge in New Jersey struck down a state law that banned guns in casinos because even though casinos did not exist in the early republic, a French colonial governor operated one in the 1750s in New Orleans, and he did not appear to ban firearms inside it.

Rahimi challenged his conviction under Bruen; the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in his favor last spring. The three-judge panel took a narrow approach to using the history-and-tradition test, concluding that there were no founding-era laws where state legislatures had disarmed anyone accused of domestic violence. The reason is obvious: While domestic violence itself is not new, American law did not generally recognize the concept until the twentieth century. Women in the early American republic typically could not serve as or elect members of the state legislatures that wrote the “historical analogues.”

Roberts, writing for the court on Friday, squared the circle by looking to roughly similar measures that disarmed dangerous persons. He cited the existence of surety laws, a colonial-era system that obligated someone to avoid committing future acts of violence by posting a bond that would be forfeited if they did so. Roberts noted that legal scholars had found instances where these laws were applied by women against their husbands. He also pointed to “going armed” laws, which generally forbade people from bearing arms to “terrify” others.

“Taken together, the surety and going armed laws confirm what common sense suggests: When an individual poses a clear threat of physical violence to another, the threatening individual may be disarmed,” he wrote. “Section 922(g)(8) is by no means identical to these founding era regimes, but it does not need to be.”

Thomas, writing in dissent, found those historical analogues to be unconvincing. He instead focused on the harm to Rahimi by unfairly depriving him of his individual right to bear arms. He noted that the law in question would disarm people without trial, which he opposed. “This case is not about whether States can disarm people who threaten others,” he wrote. “States have a ready mechanism for disarming anyone who uses a firearm to threaten physical violence: criminal prosecution.”

But the rest of the court was unpersuaded. Five justices wrote concurring opinions to flesh out their views on Friday’s ruling, on Bruen, and on originalism itself. For Justice Neil Gorsuch, the case was easily resolved because it was a facial challenge to the disarmament provision, meaning that the court had to decide it was unconstitutional in all potential cases—a high bar to clear. He left the door open to future challenges on specific applications of it.

At the same time, he found it necessary to defend originalism from its critics. “Come to this Court with arguments from text and history, and we are bound to reason through them as best we can. (As we have today.)” Gorsuch wrote. “Allow judges to reign unbounded by those materials, or permit them to extrapolate their own broad new principles from those sources, and no one can have any idea how they might rule. (Except the judges themselves.)”

So did Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who implicitly acknowledged the problems that Bruen had wrought. At the same time, he also insisted that it was preferable to the balancing tests used in other areas of constitutional law, which he compared to legislating from the bench. “Deciding constitutional cases in a still-developing area of this Court’s jurisprudence can sometimes be difficult,” he wrote. “But that is not a permission slip for a judge to let constitutional analysis morph into policy preferences under the guise of a balancing test that churns out the judge’s own policy beliefs.”

The most interesting concurring opinion came, as expected, from Justice Amy Coney Barrett. Last week, in a First Amendment case involving trademarks, the court’s second-newest justice publicly took issue with the originalist approach used by Thomas in that case. While Thomas had searched for historical analogues in trademark law to resolve it, Barrett disagreed with the inquiry itself.

“Relying exclusively on history and tradition may seem like a way of avoiding judge-made tests,” she wrote in a concurring opinion. “But a rule rendering tradition dispositive is itself a judge-made test. And I do not see a good reason to resolve this case using that approach rather than by adopting a generally applicable principle.”

That cautious stance may have broader implications for how Barrett handles future constitutional questions. In the short term, most observers took that concurring opinion as a sign that she might broaden Bruen’s history-and-tradition test. As expected, she used her concurring opinion on Friday to explain why it was inappropriate to be too specific when searching for historical analogues to modern gun laws.

“Imposing a test that demands overly specific analogues has serious problems,” she wrote. “To name two: It forces 21st-century regulations to follow late-18th-century policy choices, giving us ‘a law trapped in amber.’ And it assumes that founding-era legislatures maximally exercised their power to regulate, thereby adopting a ‘use it or lose it’ view of legislative authority. Such assumptions are flawed, and originalism does not require them.”

Barrett criticized what she saw as a fly-by-night approach to originalism, where random bits of historical evidence are transmuted into evidence of historical tradition. “As I have explained elsewhere, evidence of ‘tradition’ unmoored from original meaning is not binding law,” she wrote, citing her opinion in the trademark case last week. “And scattered cases or regulations pulled from history may have little bearing on the meaning of the text.”

Some of this criticism is undoubtedly aimed at the lower courts, which have taken a wide range of approaches to the Bruen test. She specifically pointed out the “flawed” approach used by the Fifth Circuit, which she described as demanding “overly specific analogues” to existing gun regulations. Barrett did not repudiate Bruen and cast Rahimi as a natural successor. But to clarify Bruen is also to change it. “‘Analogical reasoning’ under Bruen demands a wider lens: Historical regulations reveal a principle, not a mold,” she explained.

The court’s three liberal justices took two different approaches in their own writings. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, who joined the court after Bruen was decided, emphasized that the problem was Bruen itself. She noted the instability that it had produced in the lower courts stood in sharp contrast to the post-Heller, pre-Bruen era, where most of the courts had coalesced around a workable balancing test.

Jackson concluded that the Rahimi decision “inches that ball forward” toward something more reliable. “But it is becoming increasingly obvious that there are miles to go,” she concluded. “Meanwhile, the rule of law suffers. That ideal—key to our democracy—thrives on legal standards that foster stability, facilitate consistency, and promote predictability. So far, Bruen’s history-focused test ticks none of those boxes.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who wrote a concurring opinion joined by Justice Elena Kagan, could have also pointed out that she and the court’s other liberals predicted this problem three years ago. Instead, she played along with the other five conservatives’ narrative that Rahimi was simply clarifying Bruen, which emphasized Thomas’s own isolation from the rest of the court.

“If the dissent’s interpretation of Bruen were the law, then Bruen really would be the ‘one-way ratchet’ that I and the other dissenters in that case feared, ‘disqualifying virtually any representative historical analogue and making it nearly impossible to sustain common-sense regulations necessary to our nation’s safety and security.’” Sotomayor wrote, quoting from now-former Justice Stephen Breyer’s dissent in Bruen. “Thankfully, the court rejects that rigid approach to the historical inquiry.”

Thomas’s isolation in Rahimi does not imperil the court’s conservative majority. Nor does it mean that Thomas won’t write important decisions going forward—indeed, he already released significant majority opinions on the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and on federal trademark law this term. More decisions may come in the next week as this term draws to a close.

The real question now is whether Bruen was a high-water mark for Thomas’s influence on the court. It is often claimed that the two chief justices with whom he has served, Roberts and William Rehnquist, were reluctant to assign major opinions to Thomas because of his idiosyncratic legal views, which made it more difficult to form workable majorities in 5–4 cases. Bruen was a sharp reversal of this trend and a major chance for him to write a landmark decision. If there is one subtext to today’s Rahimi opinions, it’s that he blew it.