Six months before the most fateful election of our lifetimes, we are entering that moment in the campaign when model makers rush onstage hawking their presidential predictions. And, no, we are not talking about hobbyists who put ships in a bottle or glue together plastic replicas of World War II fight planes. These model makers are election theorists from academia, economic forecasting firms, and polling websites who offer their presidential forecasts based on their proprietary formulas—many of which are blithefully unconcerned with the identities of the actual White House contenders.

To oversimplify a bit, these mathematical approaches to political soothsaying involve combining some variant of presidential approval ratings, economic growth numbers, the inflation rate, prior election returns, and an exclusive blend of herbs and spices to reveal who is going to win long before anyone votes.

Almost nothing scares Democrats more than those ominous three words: “presidential approval rating.” But context is badly needed.

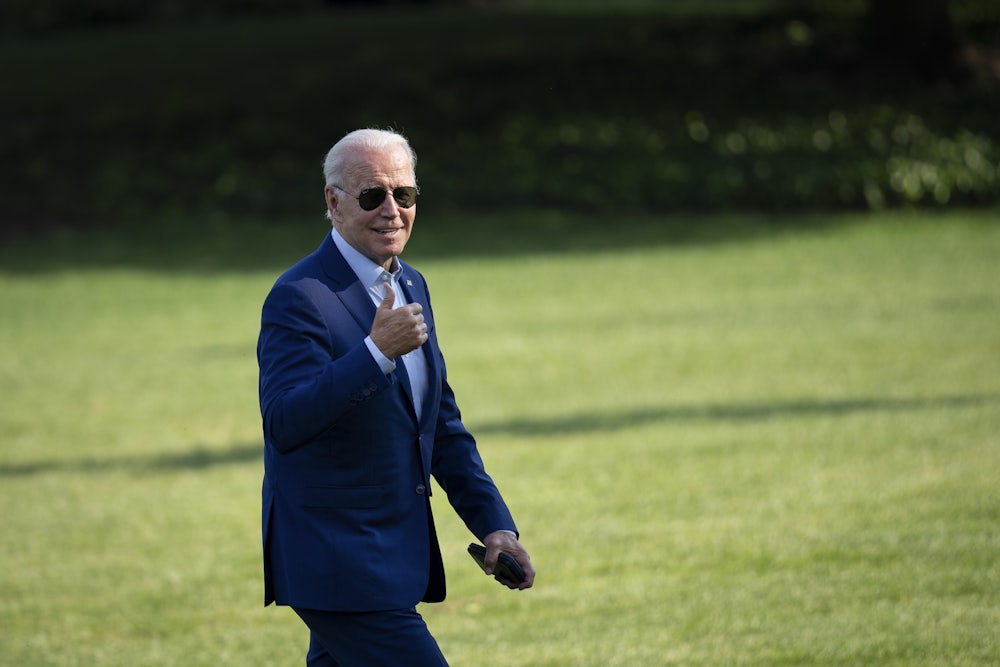

Gallup, which has been charting presidential popularity for more than 70 years, recently released a report showing that Joe Biden’s approval rating at the beginning of the fourth year of his presidency is lower than that of any elected president dating back to Dwight Eisenhower in 1956. Even Jimmy Carter, George H.W. Bush, and Donald Trump—three incumbents who failed to retain the White House—had Biden beaten at this point in their respective presidencies.

On the surface, it looks dire since it is obvious that how voters rate a president’s job performance will play a major role in shaping their ballot choices.

With his approval rating averaging a paltry 38.7 percent over the last three months, it is impossible for Biden to run a “Morning Again in America” reelection campaign, no matter what the jobs numbers are. And Biden’s problem is not just with Gallup, since the aggregate numbers at the survey website FiveThirtyEight give Biden 38.9 percent.

Until 15 years ago, approval ratings were volatile and presidents routinely polled well over 60 percent in Gallup surveys. In the wake of the Gulf War in early 1991, George H.W. Bush had a stunning approval rating of 89 percent. Two years later, Bush was a former guy. Bill Clinton’s approval rate hit 73 percent at the end of 1998 as he was being impeached. And in early 2004, as the Iraq War was fast becoming a quagmire, George W. Bush was still polling over 60 percent.

But since the early months of Barack Obama’s presidency in 2009, no incumbent has hit the 60 percent mark. There are many causes for the unprecedentedly sour mood in the electorate, including enhanced partisan passions. My own guess is that the Great Recession of 2008–2009 may have permanently upended voter trust in any president.

But for Trump and Biden, 60 percent represents the Mount Everest of poll numbers. Stunningly, Trump never once in his presidency broke the 50 percent mark in the Gallup numbers—he would still go on to win more than 74 million votes, the second-highest total of any presidential candidate. Biden, at least, was running over or near 50 percent until the calamitous withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021.

Let me be clear: Six months out, after two agonizingly close elections, I am not in the business of making predictions. That is too lucrative a sideline for everyone on cable TV panels—and it seems rude for me to try to horn in.

But what I think I do know is that there is limited value in desperately searching for signs and portents from prior elections, particularly those from the twentieth century. The list of factors that make 2024 sadly and frighteningly unique is lengthy: A felony trial in Manhattan, the comparative unpopularity of both Trump and Biden, the grim reality that whoever is elected will be in his eighties during his term in office, the increasingly deranged tenor of Trump’s threats about a second term based on retribution, the hangover from the worst pandemic in a century, and, of course, the aftereffects of a certain Trump-inspired insurrection.

When does political time become discontinuous? Some determined political analysts will try to exhume lessons from the dreary rematch election of Benjamin Harrison and Grover Cleveland in 1892. Or maybe they will argue that the proper parallel is the three-way election of 1912 featuring incumbent William Taft, Bull Moose crusader Teddy Roosevelt, and the victorious Woodrow Wilson.

Sorry, I have problems drawing epic conclusions from elections that were played out in the days before radio.

But even more recent examples falter. When Jimmy Carter lost the presidency in 1980, the internet was a futuristic idea not much more plausible for most Americans than flying cars. When George H.W. Bush was defeated in 1992, Google was an obscure mathematical term rather than the most widely used search engine. Even 2020, as we were disinfecting our groceries and nervously counting rolls of toilet paper, seems like it belongs to another century.

If you must brandish a historical precedent, I have one for you that did not show up on the Gallup roster of the nine elected presidents who polled better than Biden. The Gallup list did not include Harry Truman because of the technicality that he took office after the 1945 death of Franklin Roosevelt.

In April 1948, Truman limped home in the Gallup Poll with a dispiriting 36 percent approval rating. That, by the way, is lower than Biden’s current numbers. And as history junkies may recall, Truman pulled off the biggest upset in modern politics. Maybe it is time for Amtrak Joe to dust off the revered tradition of a whistle-stop tour of the Midwest.