The American Conservative magazine published an article last week in which the author, Peter Tonguette, argued that Trump should be able to run for a third term in office in 2028. This drew some attention in non-Trump circles as a potential trial balloon by Project 2025, the authoritarian policy agenda that is guiding Trumpworld right now.

Tonguette argued that Trump’s victory in the GOP primary contest this year shows that voters still support him—and that they should be allowed to do so indefinitely. “As the primary season has shown us, the Republicans have not moved on from Trump—yet the Twenty-second Amendment works to constrain their enthusiasm by prohibiting them from rewarding Trump with re-election four years from now,” he wrote, perhaps getting ahead of himself a bit.

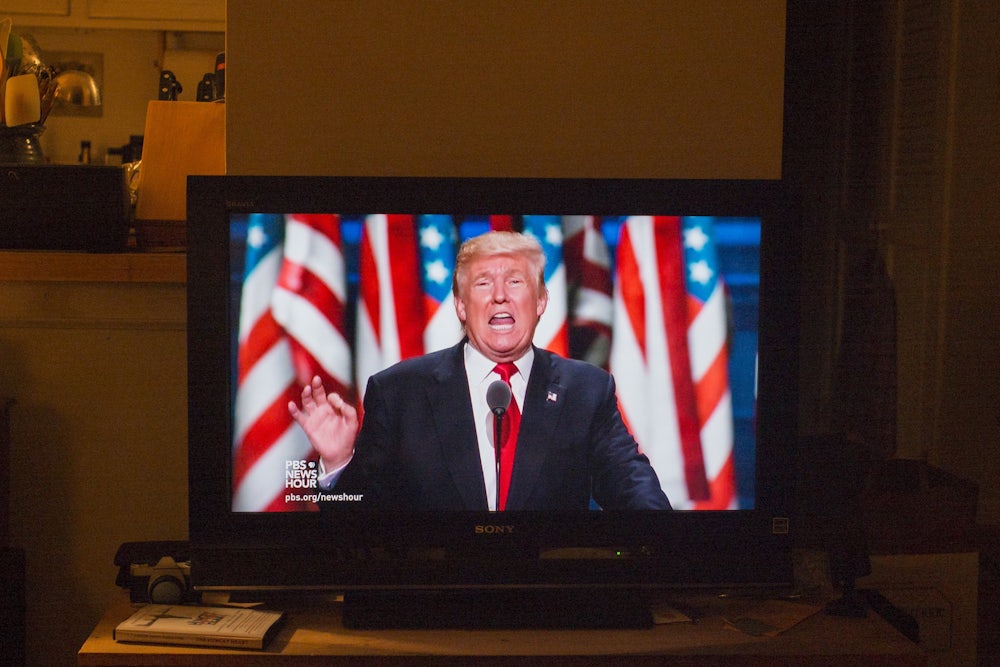

I do not doubt that Trump would run for a third term if he could. He has addressed the possibility before, suggesting in 2020 that he should get to run for one “because they spied on my campaign,” referring to his political opponents. And at a closed-door fundraiser in 2018, Trump also favorably referred to Chinese President Xi Jinping for eliminating the two-term limit in that country. “He’s now president for life, president for life, and he’s great,” he reportedly told his supporters. “And look, he was able to do that. I think it’s great. Maybe we’ll have to give that a shot someday.”

But Tonguette’s article does not appear to foreshadow an actual constitutional amendment on which Trumpworld might campaign. Instead, this offering—as well as his other writings—seems to confirm the political and philosophical hollowness of Trumpism and how it exists, if not as a vehicle for its supporters’ grievances, then primarily as a form of nihilistic entertainment for them.

While Tonguette frames his argument in democratic terms, American voters have, in fact, never truly elected Donald Trump to be their president. Hillary Clinton received three million more votes than Trump in 2016. Joe Biden received seven million more votes in 2020. Trump only made it into the White House because a structural flaw in the Constitution occasionally gives the presidency to someone who comes in second place. (Once bereft of the Electoral College’s unique advantages, Trump then attempted to retain office by fomenting an insurrection, a move that should have tabled the notion that he was somehow a “popular” figure in the democratic sense indefinitely.)

None of this math figures into Tonguette’s calculus. The real triumph of democracy here, he wrote, was Trump’s ability to win over the Republican Party’s base. “The primary voters and caucus-goers who chose Trump did so in spite of January 6, the prosecution of the former president, or even the popularity in some MAGA quarters of Ron DeSantis,” he wrote. “They chose him because they damn well felt like it.”

Trump often referred to his GOP approval ratings as if they ultimately mattered more than his standing with the general electorate. Tonguette simply repeats this phenomenon. “This is democracy in action: The voters surveyed the scene, tuned out the noise, and selected the man the rest of the world loves to hate,” he continued. “What could be more democratic than voting for your preferred candidate against the advice—the warnings, the threats, the fear-mongering—of your betters?”

It’s worth noting that Tonguette does not actually describe how the Twenty-Second Amendment should be overcome. With a vague reference to Prohibition’s reversal, Tonguette suggests that a new amendment might be drafted and enacted to repeal it. That would require the assent of two-thirds of both houses of Congress and three-fourths of the state legislatures within the next five years. Luxembourg is more likely to win every gold medal at the Olympics this summer.

This lack of details isn’t surprising. Tonguette is a culture writer, and an accomplished one at that. He writes frequently on a variety of right-of-center websites about books and film, and he has published a biography of New Hollywood director Peter Bogdanovich. I do not point out Tonguette’s usual beat to suggest he is unsuited to write about Trump or about contemporary American politics. Quite the opposite, since Donald Trump is a creature of spectacle whose primary medium is sound and screen.

There are many Trump voters who support him for the entertainment value, as Tonguette knows well. Earlier this year, he wrote an article titled, “My Mother Loved Donald Trump,” where he reflected on why his own mother, who had recently passed away, had so adored the former president. While his own support for Trump came belatedly, and only after some skepticism, Tonguette noted that his mother backed Trump from the moment he came down the Trump Tower escalator in 2015.

“Even though I was the one who had established himself as a writer in various right-of-center magazines, my mother was the one who first saw the promise and logic of Trump,” he wrote. “Like millions of others—but before me—she recognized his announcement speech at Trump Tower as something almost never seen in our political culture: a man operating under no obligation to any person, party, ideology, or standard of behavior or speech, who was willing to call balls and strikes on the issues of the day, including immigration, trade, what we then called political correctness.”

This was a bonding moment—and a strange one at that. “Our family was united as we soaked in the debates between Trump and Hillary Clinton—laughing at the coup de grâce of Trump having invited Bill Clinton’s accusers to the town hall forum—and stayed up late as Trump emerged victorious on election night,” Tonguette wrote. It’s worth noting that Trump invited these Clinton critics to the debate to deflect from taped remarks he had made where he appeared to brag about sexually assaulting women.

Even Tonguette seems to acknowledge that they saw Trump as an entertainer first. He described how his mother used to regularly follow pop culture like the Oscars until turned off by “the undisguised radical leftism that had overtaken the mainstream media since Trump’s arrival,” at which point watching his rallies became her primary form of entertainment. He estimated that his mom watched every Trump rally from the 2016 and 2020 election cycles, and even most of the ones after that. This is no small feat considering that Trumpworld didn’t have anything akin to NFL Sunday Ticket.

From these writings, Tonguette stands out as an oddity. For one thing, he seems to be one of the last people to earnestly believe the Trump mythology of 2016 that most others have since abandoned or modified. He approvingly writes at one point that his mother claimed that Trump was a necessary reaction to “Barack Obama’s far-left presidency,” which left the country in such a dire state that it required “a man wealthy enough to reach his own opinions independent of donors, gurus, and think tanks, and uncouth enough to express them.” This was doubtful at best in 2016; it is almost amusing now that he is turning the GOP’s donor apparatus into his own legal defense fund.

Second, and perhaps even more surprisingly, Tonguette appears to be one of the only Trump supporters who still refers positively to democracy. A great many Trump supporters belong to the “It’s a republic, not a democracy” school of conservative thought, which is built around rationalizing the House’s gerrymandering, the Senate’s geographic disparities, and the Electoral College’s existence. Most of them now approve of his coup attempt on January 6, 2021. Some are just undiluted fascists.

Yet Tonguette does not appear to be among any of them. (He does not mention January 6 except in passing, though he seems to not find it disqualifying.) He earnestly criticizes the Twenty-Second Amendment because of the “artificial limits it places on voter choice.” Then he goes on to make what he describes as an “ethical argument” for repealing it in Trump’s case, if such a thing is possible.

“If a man who once was president returns, after a series of years, to stand again for the office and proves so popular as to earn a second nonconsecutive term—as Trump seems bound to do—to deny him the right to run for a second consecutive term cuts against basic fair play,” he argued. “If, by 2028, voters feel Trump has done a poor job, they can pick another candidate; but if they feel he has delivered on his promises, why should they be denied the freedom to choose him once more?”

It is worth noting here that Tonguette does not say why he thinks Trump should run for a third term, beyond because he and a great many Republican voters would want it to happen. Franklin D. Roosevelt won a third term in 1940 because he argued he would provide stability and experience after the outbreak of World War II. That extraordinary crisis persuaded millions of Americans to set aside George Washington’s two-term tradition, overcoming a barrier that Theodore Roosevelt and others had failed to surmount.

But there is no explanation here of what Trump has done to merit a third term in Tonguette’s eyes. He does not point to any policy proposals for the future; he does not even reference any policy achievements by Trump in the past. Indeed, one gets the sense from Tonguette’s writing that his support for Trump is driven out of a sense of entertainment, of punching back at the left, of deriving joy and amusement from Trump’s haranguing of them.

“Yes, his charisma and celebrity were part of it, but he marshaled those attributes to do something critical to a functioning democracy: He boiled down issues that had long been rendered needlessly fancy, complex, or intractable by professional politicians,” Tonguette claimed in his January article. “His slogans, catchphrases, and rallying cries were once mocked—and are now laughably described in apocalyptic terms by our woke cultural commissars—but they had the practical effect of making political creatures out of people who would otherwise tune out politics.”

Some political scientists have described this phenomenon in more precise terms. They see a nihilistic desire among some voters to actively share misinformation and to burn down social and political institutions for the sake of burning them down. As The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson recently explained, there is a sense here that some voters aren’t driven by specific policy goals or concrete political beliefs, but by a sense of boredom, resentment toward hazily defined “elites,” and a “need for chaos.”

Trump always had the uncanny ability to instill the idea that he could be the avatar of this chaos and that he really was doing it on behalf of his followers—what Tonguette described more pleasantly as “the gift for making his supporters feel as if his wins were theirs.” In another article on Trump’s multimillion-dollar fraud and defamation penalties, Tonguette argued that he and Trump’s “blue-collar and middle-class supporters” simply “believe that what Trump earned through his business ventures he should be free to keep,” before turning his ire toward Rachel Maddow and E. Jean Carroll for trying to steal it from him.

I do not disagree that the Constitution’s two-term limit is antidemocratic, and I am not necessarily against repealing it. But I feel comfortable saying that repealing the Twenty-Second Amendment is not what Tonguette truly wants. What he is really hoping for is simply that his family’s favorite TV show stays on the air, no matter how many other people and families will suffer for it—or, perhaps, because they will.