Last week Vice, the media company where I frittered away a third of my life, announced that it was essentially shutting down its editorial operations. This meant several hundred people would lose their jobs—a practically weekly occurrence in journalism these days—and that I had to spend an annoying amount of time archiving the portfolio-worthy stories I wrote or edited there. Collapsing media companies, and there are a lot of them right now, sometimes delete their websites. Vice insists it will maintain its website, but if one day it changes its mind—because maintaining even a dormant site costs considerable money—then all evidence that I did anything productive during the 2010s would disappear.

That little digital archive is sitting on my computer now, a few feet away from the stacks of physical Vice magazines I worked on. These battered glossies are going to outlive the company that published them, which is ironic since Vice the company spent years running away from Vice the magazine and its sordid reputation. In my 12 years at Vice, I watched it grow up, hire people who weren’t skaters or cokeheads, and gentrify just like the Williamsburg neighborhood surrounding its office. Vice was intent on becoming a mainstream news organization, which meant an unslakable thirst for investors, comically inflated valuations, and the inevitable succession of expansions, “pivots,” and cutbacks.

In hindsight, Vice’s death was foretold by that ambition. Had it remained a niche print magazine, it might still be alive today.

Stories about the end of Vice tend to lump it in with other failing digital media brands. And it’s true that Vice suffered from the same ailments facing companies like BuzzFeed and G/O (formerly Gawker): an ad market that’s been in a long slump, social media traffic to news sources cratering, and overpaid, incompetent leadership. Cory Doctorow, the pioneering blogger, copyright activist, and science fiction author, portrayed Vice’s end in familiar terms: Hardworking, passionate journalists are producing incredible, important investigative work, but are betrayed by corrupt, greedy executives. Vice’s founders, he wrote, “built a massive, highly lucrative media empire on [young people’s] free labor.” Doctorow praised Vice’s tech coverage team in particular (they were pretty great), and declared, “Whatever problems Vice had, they weren’t problems with Vice’s workers—it was a problem with Vice’s bosses.”

Doctorow meant to be scathing, but if anything he was too generous. Vice was only “highly lucrative” in the sense that it had a lot of money sloshing around. It had a big fancy Brooklyn headquarters, a dozen or more international offices, and hundreds of people on the payroll, some of whom would fly around the world to report from conflict zones. As it grew, it founded a record label and an ad agency, acquired smaller media companies like Refinery29 and i-D, and had TV shows on MTV and HBO before getting its own cable channel. The company even bought a bar and started brewing its own beer, called Old Blue Last, which tasted like the tail end of a long night out. During one holiday party, co-founder Shane Smith handed out envelopes to employees containing $1,500 in cash.

But upon what was that excess built? It wasn’t all those award-winning journalists—they got hired, for the most part, after Vice was already on the rise. It wasn’t that Vice went through a period of gangbusters profitability—the most optimistic insiders only ever claimed “intermittent” profitability. In reality, it was bankrolled almost entirely by investors who believed that it was poised for world domination. There was such optimism among these funders that in 2017 Vice was valued at $5.7 billion, to which a reasonably plugged-in Vice employee might have responded, “with a B?”

These investors believed in Vice because they believed in Smith, who had Trumpian talents of self-conviction and bluster. He sold them on the idea that Vice had a unique, unbreakable connection to millennials (who were then young people) and that it was the future of news, destined to destroy CNN. And at least when Smith started making this pitch, the thing backing him up was the reputation of the irreverent, caustic, irresistible magazine.

“We do stupid smart and smart stupid” was how my first boss at Vice summed up the magazine’s ethos. It was stunt journalism, and arguably not even journalism, but it was daring and provocative. Before I got there, the staff all went to a Native American reservation and edited and wrote all the articles from there (including some by reservation residents). There was a “gross jar” that was a jar filled with gross stuff; this was a recurring column. We had a whole series where we’d give someone acid, send them somewhere weird, and film them. We dressed dogs up in bondage gear for one fashion shoot, and sent models down to Occupy Wall Street for another. We had a try-anything writer who cooked and ate her own vaginal discharge for one article, and covered herself in live raccoons for another.

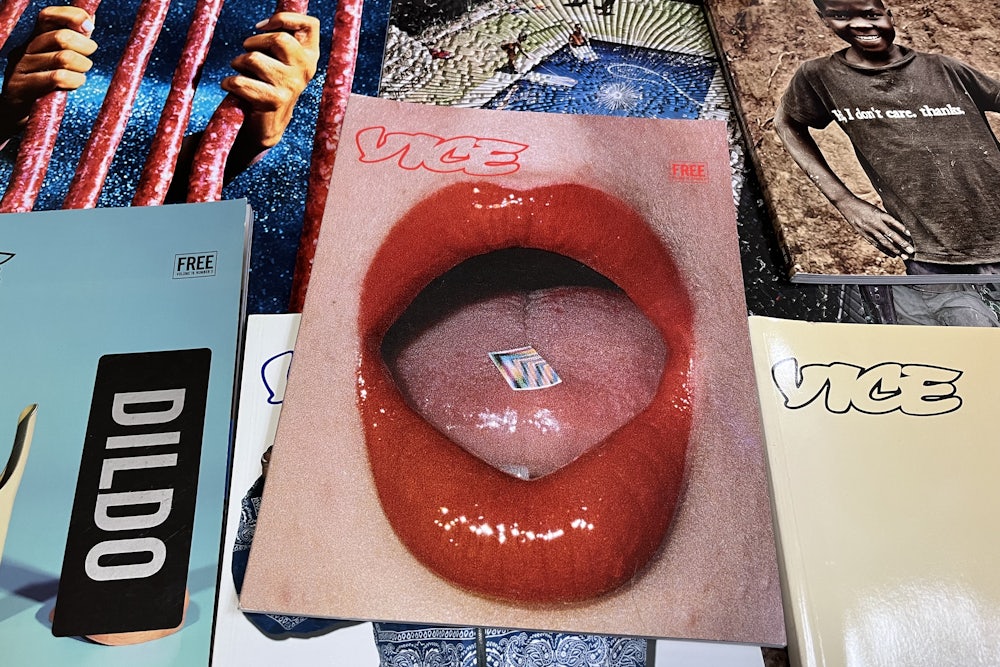

We published fiction and photo essays and incomprehensible screeds and things that probably shouldn’t have been published. One cover was adorned with a photo of a dildo by renowned Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan, covered by a sticker that said “DILDO.” The DOs & DON’Ts, where editors and comedians roasted people in photos submitted by readers, were both hilarious and, by today’s standards, unforgivably vicious. The magazine was stupid, and especially during the tenure of founding editor Gavin McInnes—who would go on to found the Proud Boys—it could be racist, sexist, and cruel. But it touched a chord, as did some of Vice’s early videos. If you smoked a ton of weed in the 2000s, you probably ended up in someone’s ratty apartment watching either Smith’s visit to North Korea or the Epicly Later’d skate documentaries.

The coverage of Vice’s demise rarely mentions this era of the company, a convenient omission for a lot of people. The serious journalists Vice hired in droves starting around 2014 (when Vice News was launched as a standalone brand) understandably didn’t want to be associated with McInnes or magazine features like “Paintballing With Hezbollah.” The company spent years polishing its image, beginning in 2008, when it cut ties with McInnes (when it became clear that his ironic racism wasn’t all that ironic). If the company got a lot of search traffic from “How to Suck Your Own Dick”—an all-time SEO headline—the story it wanted to tell to its own employees, media reporters, and especially investors was that it was a global news organization.

The change accelerated in the mid-2010s. The website and magazine were redesigned, and the fashion photo spreads—once the lavish centerpieces of every issue—were discontinued, the overworked fashion editor laid off. The weird stuff began to be marginalized. In 2018, the magazine’s frequency dropped from monthly to quarterly, ending the photo and fiction issues. A subsequent tweak to the website removed the issue-by-issue magazine archive; old articles are still online, but in most cases their formatting has degraded and the images have disappeared. You can only find the DOs & DON’Ts through Google. A skeleton crew of staffers did keep the print product going, though the magazine was barely acknowledged by the company that owned it. It even came back after a pandemic-related hiatus, producing a few issues in 2021 helmed by editorial director Kate Dries. (The last-ever issue was called “The Indulgence Issue.”)

In ditching its original identity, Vice gained respectability but couldn’t make respectability work for it. How, as a former Vice executive told New York magazine in 2018, “do you scale the essence of a punk-rock magazine into a multibillion-dollar media company? There is no real answer. At some point, what got you there isn’t what you are.” If Vice needed to evolve in order to grow and attract investment, the digital media company it evolved into had serious flaws. Its in-house tech products all sucked, as anyone who ever used its CMS can attest. It was among the first companies to produce truly high-quality videos for the web, but squandered that advantage by pivoting to television and film instead of the short-form content that has since taken over social media. Its traffic numbers were inflated and sometimes outright fake.

Vice journalists did great work and garnered accolades, but that was no great achievement on the company’s part—hire journalists and you’ll get journalism. Where was the business plan? In 2014, Smith predicted Vice would bring in $1 billion in revenue by 2016; in 2022, it was only earning $600 million, $100 million below its target. By then, Smith had left his CEO post following scandals involving sexual harassment and the underpayment of female employees. But his departure didn’t change the company’s downward trajectory. How could it have, when the company was built on his otherworldly powers of spin?

Vice needed to change, of course, and not just for cynical, cozying-up-to-investors reasons. Misogyny, racism, and nihilism were ingrained in the magazine from the get-go. Could you have cut out the toxicity without losing what made Vice compelling to so many readers? Could the company have evolved not into a vaporware global news organization but a different kind of small, weird magazine? Maybe. Jesse Pearson, who was the editor in chief when I was an intern, quit to start a magazine called Apology (get it?) and it might not be famous, but it’s still going.

The simplest way to understand Vice is not as a media company but a zero interest-rate phenomenon, a property investors made speculative bets on because they had to make bets on something. A scam, in so many words, but an unusually fruitful one. Not entirely on purpose, Vice produced some exceptional journalism. It launched careers (including mine). In its corporate era, it paid quite generous salaries to some C-suiters who couldn’t save the company (assuming they were even trying to). Smith walked away with $100 million, which is an unfathomable sum to me but not all that much money, really, given Vice’s rosy picture a decade ago. Me? I’ve got an archive of web stories on my computer desktop, and some old magazines on my shelves.