Former President Donald Trump is not above the law, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled on Tuesday. The three-judge panel unanimously rejected his sweeping claims of absolute immunity from official acts committed while president. Tuesday’s ruling paves the way for the resumption of his D.C. criminal trial on January 6–related charges—unless the Supreme Court intervenes, that is.

There was no real reason to believe that Trump—or any former president, for that matter—had the level of immunity that the former president imagined he possessed. No president had ever claimed it before, the Constitution does not mention it, the Founders would have despised it. One cannot help but wonder if, way down deep in their heart of hearts, Trump’s lawyers even believed the claims they were making in court. They essentially argued that President Joe Biden could murder them and their client if he so wished and nothing could be done about it.

But the D.C. Circuit was obligated to consider it on appeal nonetheless. The court’s 57-page ruling is unsigned, a move that both signals a deep agreement among the judges on the panel and avoids the risk of making one of them a target for death threats or retribution from the former president’s followers. It easily but comprehensively dispenses with Trump’s myriad arguments for immunity.

Trump first argued that his purported immunity flowed from the Constitution’s separation of powers. Most of his argument stemmed from a line in Marbury v. Madison, the foundational 1803 ruling that established judicial review, where Chief Justice John Marshall wrote that a president’s “official” acts “can never be examinable by the courts.”

The panel noted that this was a misreading of Marbury, which also distinguished between a president’s discretionary acts and his ministerial ones. Discretionary acts like naming a specific person to an ambassadorship or issuing a pardon aren’t subject to judicial review, but ministerial ones, such as enforcing federal criminal laws, are.

Trump’s actions, the panel concluded, fell within the latter category and thus could be reviewed by the courts. “Here, former President Trump’s actions allegedly violated generally applicable criminal laws, meaning those acts were not properly within the scope of his lawful discretion; accordingly, Marbury and its progeny provide him no structural immunity from the charges in the indictment,” the panel wrote.

Trump’s next set of claims revolved around public policy considerations. He claimed that allowing criminal prosecutions of former presidents would undermine the executive branch’s ability to carry out its constitutional functions. If former presidents could face criminal charges, Trump warned, it might have a chilling effect on how presidents wield executive power. While undoubtedly biting their judicial tongue, the panel effectively noted that a chilling effect on criminal conduct was precisely the point of criminal laws.

“Moreover, past Presidents have understood themselves to be subject to impeachment and criminal liability, at least under certain circumstances, so the possibility of chilling executive action is already in effect,” it noted, citing the experiences of Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton. “Even former President Trump concedes that criminal prosecution of a former President is expressly authorized by the Impeachment Judgment Clause after impeachment and conviction.” (We’ll come back to that clause later.)

The court was careful to balance specificity with generality. While it rejected Trump’s arguments as he made them, the panel also set aside thornier constitutional questions. In a footnote, the panel noted that its reasoning only applied to former presidents, leaving open the question of whether a sitting president can face criminal charges. And the panel noted that its ruling was based on the specific charges at hand, which alleged that Trump tried to overturn the presidential election results and illegally stay in office.

The latter caveat, if anything, made the panel even less inclined to countenance an immunity claim. “We cannot accept former President Trump’s claim that a president has unbounded authority to commit crimes that would neutralize the most fundamental check on executive power—the recognition and implementation of election results,” it wrote. “Nor can we sanction his apparent contention that the executive has carte blanche to violate the rights of individual citizens to vote and to have their votes count.”

The most bewildering and misleading argument for immunity that Trump made—which is really saying something—is that his prosecution was foreclosed by his acquittal in his second impeachment trial. He claimed that the Constitution’s language on impeachment, which says that “the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment, and Punishment, according to Law,” meant that he could only be tried for January 6–related charges if he had been convicted by the Senate during his second impeachment trial.

This is a nonsensical theory that, as I noted in October, rested heavily on Trump’s legal team misreading part of Justice Samuel Alito’s dissenting opinion in a previous immunity case. The panel duly dispensed with it by noting that the weight of historical evidence suggested otherwise. “In drafting the Impeachment Judgment Clause, to the extent that the Framers contemplated whether impeachment would have a preclusive effect on future criminal charges,” the panel noted, “the available evidence suggests that their intent was to ensure that a subsequent prosecution would not be barred.”

Trump’s last and most desperate claim was that his Senate acquittal for “incitement to insurrection” also barred his prosecution on January 6–related charges under “principles of double jeopardy.” This did not fly with the panel for a few reasons, foremost among them that impeachment is not a criminal proceeding and so the double jeopardy clause does not apply. “To the extent former President Trump relies on ‘double jeopardy principles’ beyond the text of the Impeachment Judgment Clause,” the panel wryly noted, “those principles cut against him.” After all, it pointed out, federal prosecutors had not charged him with the same offense.

The D.C. Circuit’s decision is impressive not only for its clear reasoning but for the speed with which it was written. Some federal appellate courts take months to hand down rulings on complex cases, sometimes even more than a year. It took the three-judge panel only 28 days from oral argument on January 9 to the announcement on February 6. That raises hopes that Trump’s criminal trial, which had been paused during the appeal, can speedily resume. Judge Tanya Chutkan scrapped the March 4 trial date last week but will likely announce a new one in the coming days.

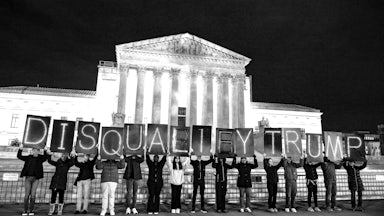

All that remains to be seen is whether the Supreme Court will take up the case. It would not be surprising if the justices decided to give a final, authoritative word on the matter. At the same time, even the most accelerated briefing and argument schedules would make it difficult for the court to issue a ruling before the end of this term. The justices are already under pressure to deliver a ruling on Trump’s disqualification case, in which oral arguments are scheduled to begin on Thursday. In this matter, the court may decide for now to let the D.C. Circuit panel’s opinion stand unless enough justices actually disagree with it on the merits. The high court will likely signal its next steps in the coming weeks after Trump’s inevitable appeal.