Last August, police in Kansas executed questionable search warrants on the offices of the Marion County Record, a weekly newspaper that has been publishing since 1869, along with the homes of the publisher and a local city councilwoman. At issue was how the paper obtained a local businesswoman’s driving record, which revealed the woman had had her license revoked for a DUI offense; she had been seeking a liquor license for her Marion restaurant. After a public outcry, the police chief was suspended, then resigned. The co-owner of the Record, 98-year-old Joan Meyer, suffered a fatal heart attack the day after the raid.

While shocking, the Marion County incident underscored the genuine power that local media still retains over our community conversations. But that power is rapidly crumbling, with worrying ramifications for American democracy. An average of 2.5 newspapers shut down across the United States each week, according to “The State of Local News 2023” (a report by Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism), and nearly 2,900 newspapers have ceased publication since 2005. Today, 204 counties in the United States are without any local news hub—and more than 1,500 have only one—leading to “news deserts” in which misinformation, bot-generated “articles,” and social media rumors go unchecked, public meetings and officials escape scrutiny, and community issues are overlooked.

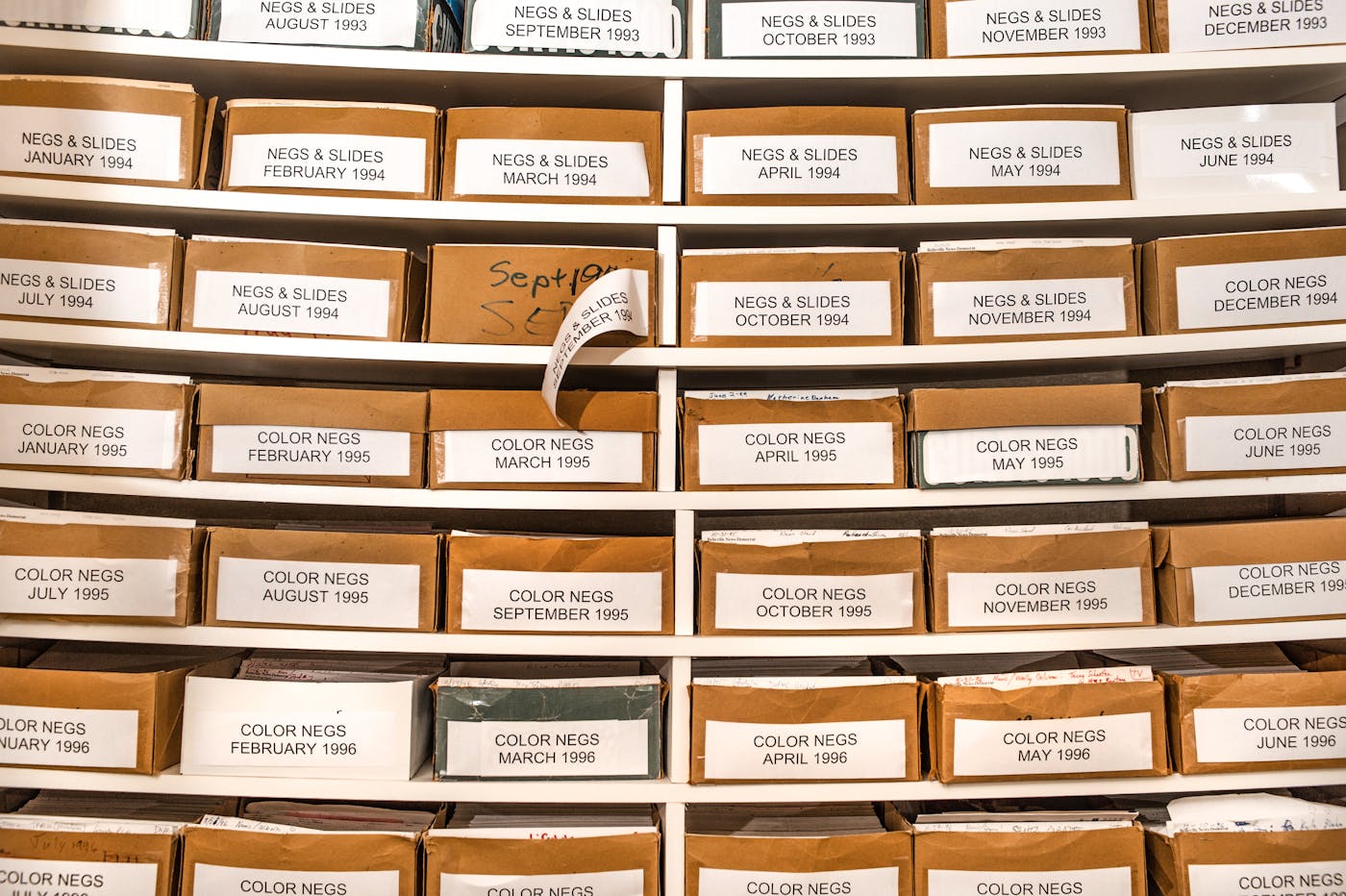

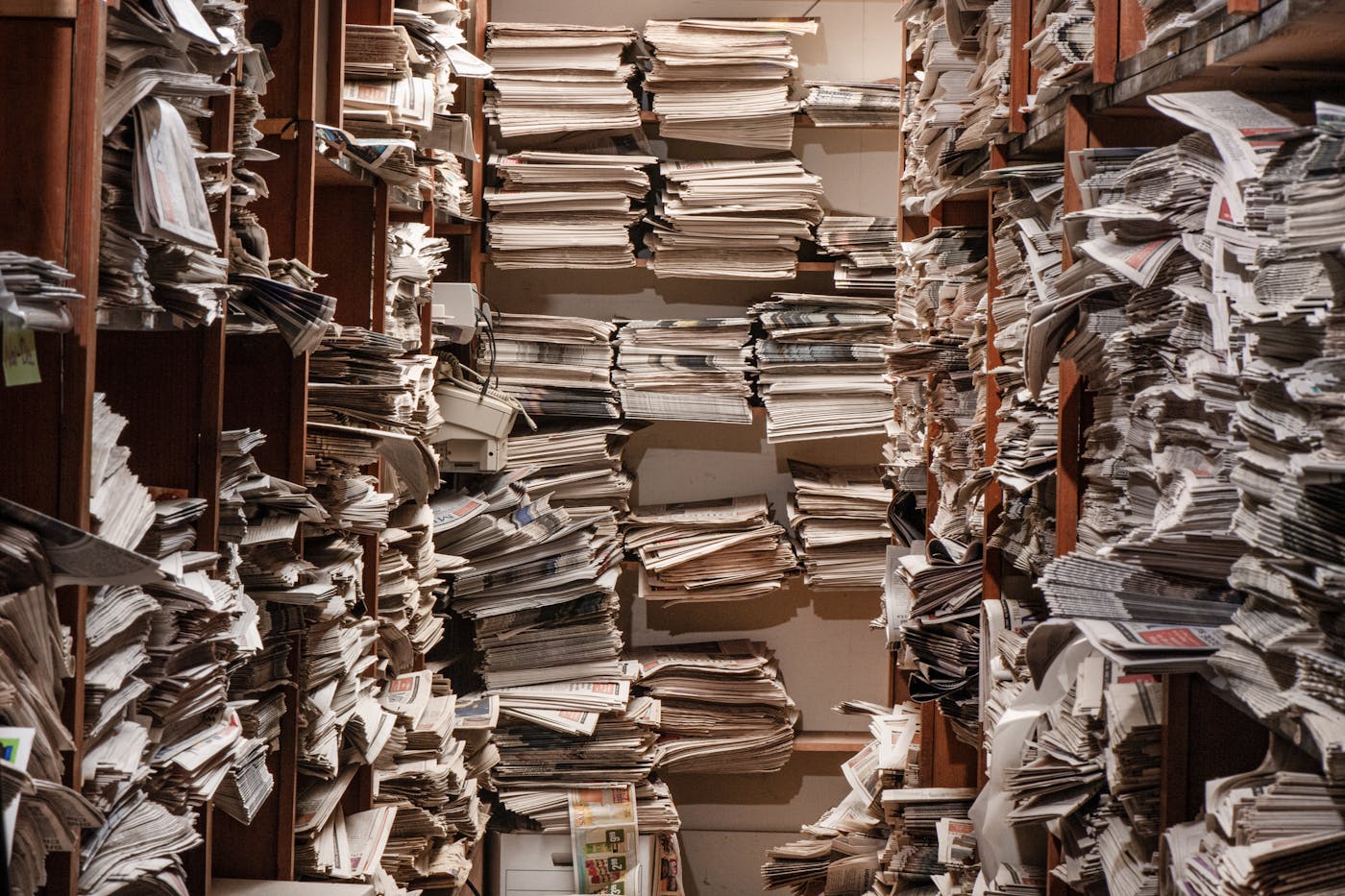

The precarity of local media was on the mind of photographer Ann Hermes during a 2015 visit to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch newsroom. The paper had just won a Pulitzer for its photographic coverage of the 2014 Ferguson uprising but had also been hit by layoffs. At the Post-Dispatch offices, Hermes said, she noticed marks in the carpet where employee desks had been removed. The moment stuck with Hermes, later inspiring her to create a visual portfolio of local newsrooms nationwide. “I figured that if I could show the coffee stains, the bottles of Tums, and the rinky-dink spaces crammed with hardworking journalists, people would see that these are not elitist institutions but people working as hard as they can, under duress, to serve their communities,” said Hermes, who herself spent years as a photographer for outlets like The Christian Science Monitor.

She has spent much of the past half-decade visiting papers in 10 states and talking to journalists about the challenge of producing vital, responsive coverage of the issues that matter most to their neighbors. “People who work in local newsrooms are thinking deeply about journalism,” Hermes observed. And they’re doing so while trying to adapt to largely hit-or-miss business models, along with dramatically reduced staff.

Not all the news about news is bad: The Medill report cites “bright spots”—areas where local news growth has occurred, staff numbers have expanded, and models for news delivery seem promising. Polarization may have helped corrode our national conversation, but those bright spots could prove a signal moment for journalism and democracy.

The Emporia Gazette

LOCATION: EMPORIA, KANSAS

FOUNDED: 1890

PRINT CIRCULATION: 2,245

“If I’m out somewhere and I tell people I’m with the Gazette, they say they’re happy that we’re here, they love that we still have a local paper.”

—Ryann Brooks, news and online editor of The Emporia Gazette

The Conway Daily Sun

LOCATION: NORTH CONWAY, NEW HAMPSHIRE

FOUNDED: 1989

PRINT CIRCULATION: 13,000

“The New York Times and [newspapers] that have an international reputation, they can survive on digital. The middle papers are really in trouble.… It’s the local papers that are doing well.”

—Mark Guerringue, publisher of The Conway Daily Sun

Post-Gazette

LOCATION: BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS

FOUNDED: 1896

PRINT CIRCULATION: 12,000 (estimated)

“People will come in here and tell me things. They trust the Post-Gazette because they know we’re not going to do sensationalism. We’re not going to do fake news.”

—Pamela Donnaruma, owner and editor of Boston’s Post-Gazette

Post Bulletin

LOCATION: ROCHESTER, MINNESOTA

FOUNDED: 1925

PRINT CIRCULATION: 11,651

“There’s ways ... to develop a hunger and an appreciation for local news, and it’s going to vary by community. We need to find the one that works for us, but it can be done.”

—Jeff Pieters, editor of the Post Bulletin

Belleville News-Democrat

LOCATION: BELLEVILLE, ILLINOIS

FOUNDED: 1858

PRINT CIRCULATION: 6,077

“You know, our goal, no matter our size, is still—it sounds like a buzz phrase—but it is to do exclusive essential journalism that makes a difference. That’s what we want to do.”

—Jeffry Couch, editor and general manager of the Belleville News-Democrat

The Daily Star

LOCATION: HAMMOND, LOUISIANA

FOUNDED: 1959

PRINT CIRCULATION: 4,000

“We get calls sometimes ... ‘Why didn’t such and such event get covered?’ I usually just have to tell them, ‘Well ... we’ve only got two people here.’”

—Connor Raborn, editor of The Daily Star

The Sacramento Valley Mirror

LOCATION: WILLOWS, CALIFORNIA

FOUNDED: 1991

PRINT CIRCULATION: 2,500

“A lot of people here, they tell me every day, ‘Keep the paper going, we need it’ because, otherwise, they wouldn’t have anything.... I think most of them think that they’re getting good coverage from our paper.”

—Donna Settle, owner of The Sacramento Valley Mirror

The Keene Sentinel

LOCATION: KEENE, NEW HAMPSHIRE

FOUNDED: 1799

PRINT CIRCULATION: 5,000

“It’s worrisome, what is going to happen when you lose the accountability ... that rules are followed and democracies upheld and all of the things that this country was founded on.”

—Cecily Weisburgh, co-executive editor of The Keene Sentinel

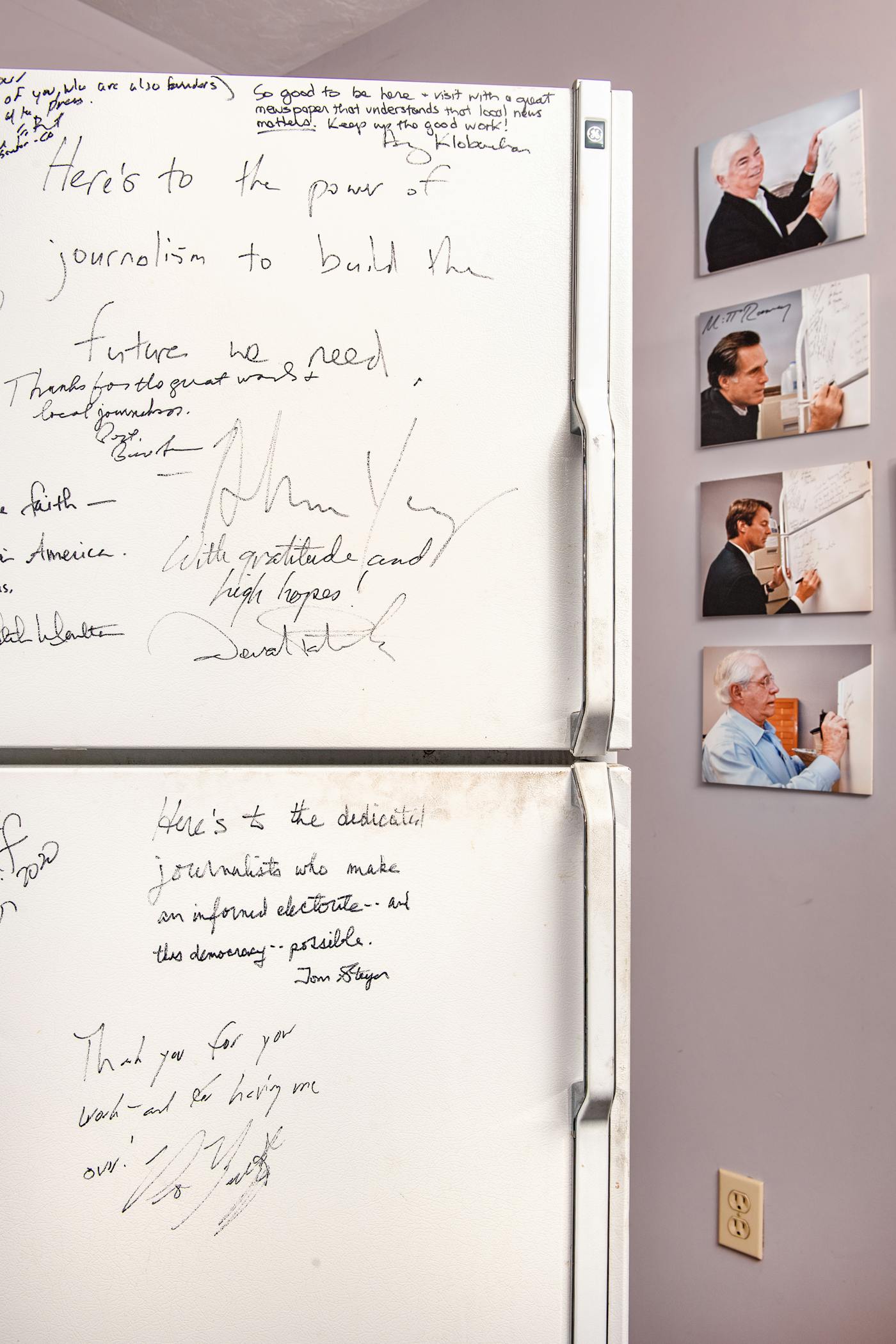

Marion County Record

LOCATION: MARION, KANSAS

FOUNDED: 1869

PRINT CIRCULATION: 5,897

“Without journalism, there’s isn’t a healthy democracy. I mean, you can’t make choices without information.”

—Eric Meyer, owner and editor of the Marion County Record