American courts and judges are usually pretty good at explaining themselves. They write opinions laying out their reasoning in detail. This informs the public, helps shape future precedent, and gives appeals courts something to work with when reviewing decisions. That can, at times, make the judiciary arguably more transparent than the executive and legislative branches.

This quality can only be truly appreciated when the courts fail to explain themselves. On Monday, the Supreme Court lifted an injunction that had blocked Border Patrol agents from cutting through razor wire installed by Texas along the southern border. The move was a victory for the Biden administration, which claimed Texas officials had obstructed them in performing border enforcement duties. It was also a defeat for Texas Governor Greg Abbott and his Republican allies in Austin, who have aggressively opposed current border-related policies.

When normal cases are heard before the court, there are extensive briefings and oral arguments and, eventually, a written decision on the ruling. But this dispute reached the justices on the “shadow docket,” the court’s mechanism for reviewing stays and injunctions issued by the lower courts. As a result, the court’s announcement at this stage in Department of Homeland Security v. Texas was perfunctory and unenlightening.

“The application to vacate injunction presented to Justice Alito and by him referred to the Court is granted,” the court announced in a short bulletin on Monday. “The December 19, 2023 order of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, case No. 23-50869, is vacated. Justice [Clarence] Thomas, Justice [Samuel] Alito, Justice [Neil] Gorsuch, and Justice [Brett] Kavanaugh would deny the application to vacate injunction.”

This tells us a few important things about what happened. For starters, it gives us the exact lineup of the 5–4 decision. With one exception, everything the court does is by majority vote. (Accepting cases for review requires only four votes.) Sometimes those votes are public knowledge, as when deciding the court’s normal complement of cases. But sometimes the vote breakdowns aren’t revealed unless the justices in question choose to make their votes known.

It’s possible for some justices on the losing side of a decision to not disclose that vote to the public. They can also choose to disclose it to send a signal. Since Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh voted to deny the federal government’s application, we logically know that the court’s three liberals, as well as Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Amy Coney Barrett, must have voted to vacate the Fifth Circuit’s injunction. Otherwise, the vote would have gone 5–4 in the other direction.

This practice transforms court-watching for lawyers, reporters, and the general public into Kremlinology. Are the four dissenting conservatives signaling some sort of heightened displeasure with the majority’s vote? Are they telegraphing the divide to Texas for future litigation strategies? Are the votes rooted in specific procedural aspects about the Fifth Circuit’s stay, or could it reflect the justices’ overall approach to the merits of the case?

Border enforcement–related lawsuits are increasingly common as Republicans ramp up their opposition to the Biden administration’s approach to the issue. Texas, the only Republican-led state on the southern border, has been particularly aggressive. Abbott has deployed the state National Guard, erected physical barriers, and even supported the passage of a new law last month that would create a Texas-specific deportation system.

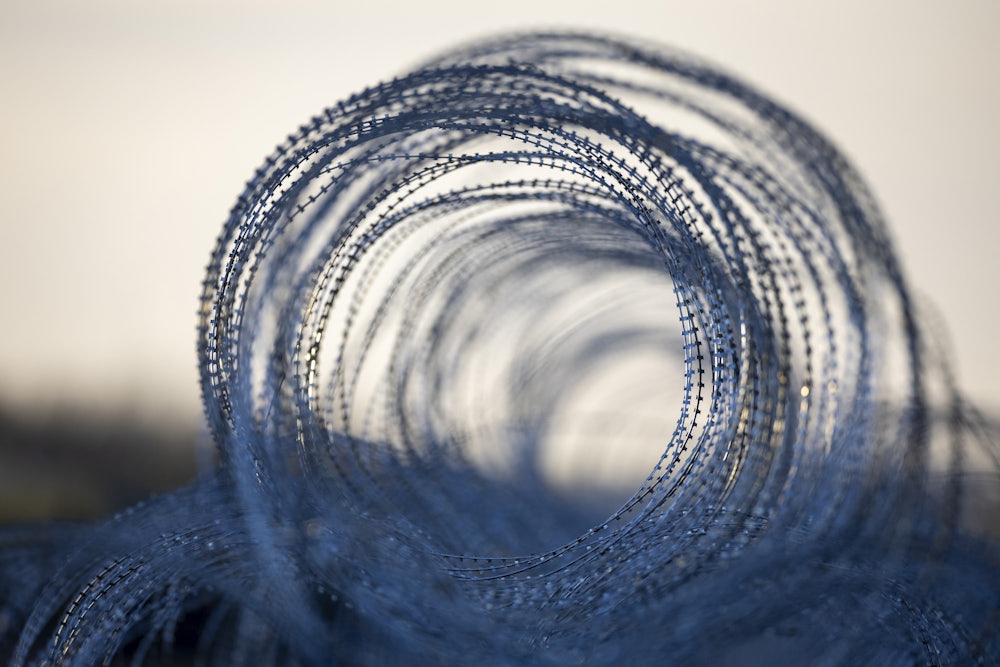

One of Texas’s tactics is the installation of miles of concertina wire in certain portions of the border. To access the border in certain places—most notably in Eagle Pass, Texas, along the Rio Grande—Border Patrol agents have cut through the wire from the U.S. side. Last fall, Texas sued the federal government in federal court for allegedly destroying state property. The federal government, for its part, countered that the destruction was necessary to carry out federal immigration enforcement policies.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which ranks among the most conservative courts in the nation, sided with Texas and enjoined the Department of Homeland Security from cutting Texas’s razor-wire barriers except in medical emergencies. Judge Kyle Duncan, who wrote for the three-judge panel, ruled that Texas had a sufficient trespass-to-chattels claim—a state-law tort for property destruction—to request the injunction and that the federal government’s arguments were unpersuasive.

In its request for the Supreme Court to intervene, the Justice Department argued that Texas had no authority to bring the lawsuit in the first place. “It is a foundational constitutional principle that the federal government is not bound by the laws or policies of any particular State in its enactment and implementation of federal law,” the department told the justices. “That principle is reflected in the multiple legal barriers to this suit.” It emphasized that the Constitution’s supremacy clause, which elevates federal laws over state ones, must defeat Texas’s lawsuit.

Texas argued that it had not run afoul of that principle. “Under the Supremacy Clause, laws passed within the scope of Congress’s enumerated powers may preempt state laws that conflict with federal mandates,” the state told the justices. “But,” it added, Congress “has never declared that property rights vanish at the border or that they exist solely ‘at the discretion, the behest, and the choice, and the desires of’ federal officials.”

In a reply brief, the Justice Department strenuously urged the justices to reject that position, arguing it could be used in bad faith to obstruct a wide range of governmental functions. “The result of Texas’s position would be that States across the country could invoke their laws to impede the federal government’s exercise of its authority,” the federal government claimed. It also not-so-subtly suggested that Texas’s actions and the lower courts’ ruling sprang mainly from policy differences over border enforcement.

“When Border Patrol agents are vastly outnumbered and face blocked access points and dangerous conditions in the river and on the bank, they must exercise judgment as to the best use of limited resources to apprehend, inspect, and process noncitizens safely and efficiently,” the department claimed, quoting from a prior Supreme Court ruling. “Texas and the lower courts may prefer for Border Patrol to operate differently, but as this Court has ‘repeated time and again, an agency has broad discretion to choose how best to marshal its limited resources and personnel to carry out its delegated responsibilities.’”

In the grand scheme of things, whether some state-owned wire is cut or not cut by Border Patrol agents should not be a high-profile legal dispute. But the heightened political sensitivities surrounding immigration have transformed it into one. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton framed the situation in dire terms in a statement after the court’s decision. “The Supreme Court’s temporary order allows Biden to continue his illegal effort to aid the foreign invasion of America,” he claimed. “The destruction of Texas’s border barriers will not help enforce the law or keep American citizens safe.”

Some Republican lawmakers went even further with incendiary rhetoric. Louisiana Representative Clay Higgins reportedly claimed that “the feds are staging a civil war, and Texas should stand their ground.” Some right-wing figures even encouraged Abbott to defy the court’s order to defeat what they describe as an invasion.

“If the Supreme Court wants to ignore that truth, which a slim majority did, Texas still had the duty, Texas leaders still have the duty, to defend their people,” Texas Representative Chip Roy told Fox News earlier this week. “It’s like, if someone’s breaking into your house, and the court says, ‘Oh, sorry. You can’t defend yourself.’ What do you tell the court? You tell the court to go to hell, you defend yourself and then figure it out later.”

Naturally, a Supreme Court opinion will not stop public officials from saying reckless and dangerous things. But the justices’ silence on the reasoning behind its actions can also be unhelpful. The court, after all, has no inherent ability to enforce the law itself. Chief Justice John Roberts is not going to fly down to the Rio Grande and stand between the Texas Rangers and the Border Patrol. The court’s power comes entirely from persuasion and explanation. And while the court’s silence on a major shadow-docket case may be its normal practice, it is also a regrettable one.