The Extinction of Irena Rey, the multilingual translator Jennifer Croft’s fun house of a debut novel, opens with a warning—not a note; not a foreword: a warning—from a translator. Quickly, readers gather that The Extinction of Irena Rey is both the real-world book we are reading and an autobiographical novel whose author, an Argentine translator named Emi, considers the woman now translating it into English her nemesis, “the monster who seems to want to ruin everything.” Alexis, the translator in question, is understandably offended by this. She also takes issue with the author’s choice to write in Polish rather than her native Spanish, whose spirit “comes whooshing through the walls of every paragraph, breaking plates and continually flicking the light switch, creating an atmosphere of wrongness and scaring the shit out of everyone’s dog.”

Linguistic haunting is just one of the many sorts of spookiness running through The Extinction of Irena Rey, which is set largely in Poland’s primeval Białowieża Forest. When the novel opens, the forest—full of poison snakes, mysterious mushrooms, and the memories of Nazi hunting parties; guarded by a mythic shape-shifter named Leshy—is under threat: An invasive beetle has moved in, and the Polish government has responded by tripling logging limits there. For the eponymous writer Irena Rey, who lives at the forest’s edge, this is an artistic crisis as well as an environmental and historical one. Irena, a literary legend and constant Nobel contender, has made her career writing sweeping, beloved works of climate fiction. But now she’s diminished, upset about the forest, and strangely reluctant to share her new manuscript, though she’s summoned all her translators to Białowieża to work on it.

Irena seems at first to be the center of the novel’s swirling creepiness. She is a performatively witchy figure, all black-magic jewelry and strange tinctures. In her house, objects are constantly disappearing; whole trunks and rooms are off-limits. More alarming than any of this, however, is her treatment of her translators. She forbids them to work with other authors, only lets them translate her work in her physical presence, subjects them to arbitrary rules like not discussing the weather, and demands that they refer to each other as “Spanish” and “German” instead of using proper names.

Emi, the novel’s narrator, objects to none of this. She worships Irena. She is confident that the other translators, including Alexis, feel just as strongly as she does; she informs us that each of them believed Irena was “warmth, she was moisture, she was light, she was the adamant perfection of a million billion snowflakes in a split second’s descent.” At first, Croft makes it impossible to tell to what degree the other translators share Emi’s childish reverence. But when Irena vanishes only a few days after summoning her translators to Poland, the group’s frantic efforts to locate or conjure her reveal the varying intensities of Irena’s hold on them. The novel becomes not just a literary thriller but an examination of the delicate mix of desire, impersonation, ambition, and selfishness that the art of literary translation requires.

At first, all eight of Irena’s translators are desperate to find her. They search everywhere, including in her latest manuscript, which they hope holds clues; they perform comical but heartfelt summoning rituals; they even stage a wedding. Emi, the most devoted of all, gives herself the impossible mission of saving the forest from logging in order to somehow bring Irena back. Soon, though, it becomes apparent that everyone but Emi is concerned primarily because Irena’s disappearance drastically impacts their finances: Irena has forbidden them to translate other writers, so if she’s gone, they have no way to pay their rent. For Emi, though, the trouble is existential. Without Irena, she feels profoundly lost—and her lostness shapes the book. Everything else, including the question of where Irena has gone, is less plot than scaffold, there to support Croft’s character writing, her ideas, and her gorgeously descriptive and exploratory prose.

Playful and beautiful language is not unexpected from a translator as gifted as Croft, who has worked with authors ranging from the young Argentine story writer Federico Falco to Polish Nobel laureate Olga Tokarczuk (a partial model for Irena Rey? Certainly Croft is tempting readers to think so, though it seems immensely unlikely that the real writer’s behavior matches the fictional one’s). Neither is it surprising that Croft plainly delights in unusual words, often turning them into Easter eggs of sorts. After the Swedish translator gets bitten by a tree adder on an excursion to the forest with Irena, his colleagues are “unable to keep from sensing the throbbing of Swedish’s hot, pomiform hand.” The basic worry here is apparent—but if you take the time to look up pomiform, or know that it means apple-shaped, the looming end of the translators’ Eden is suddenly clear.

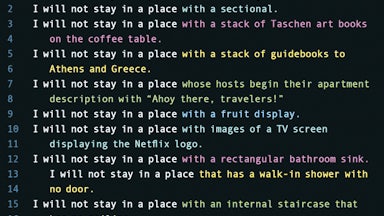

But Croft is not a thesaurus writer. She is elastic in tone, as comfortable in low registers as she is in high ones. Her prose is as funny as it is elegant; it would be propulsive if it weren’t so packed with words, phrases, and translation debates worth appreciating. The Extinction of Irena Rey is, I’d say, the first novel since Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad to pull off a chapter written in the mode of a relatively new app or program: PowerPoint for Egan, Instagram for Croft. But though Croft’s good at both Instagram-caption-as-story and, more broadly, at integrating social media and internet research into a novel about the archetypally analog subjects of nature and literature, she shines most of all in her use of a very old technology: the footnote. The Extinction of Irena Rey’s true plot happens literally below the story, where Alexis, the English translator, footnotes as she goes. At first, she just offers catty clarifications— “perhaps it will be useful to the reader to know that the author liberally employs a very royal ‘we’ throughout”—but before long, the book’s bottom margins fill up with comments, objections, and critiques of the translation philosophy to which poor author-worshipping Emi clings.

Using footnotes is itself a philosophical choice for translators, many of whom argue that doing so is too academic; that footnoting a novel makes it an object of study, not a story to be enjoyed. Alexis would likely agree with this idea, which suggests that not only the content but the presence of her footnotes is meant to undermine the novel she’s translating. Emi would certainly think so. Emi’s enmity toward Alexis is rooted partly in envy of Alexis’s beauty and assurance and partly in resentment of her U.S. citizen’s entitlement (the novel takes pains to distinguish between American, as in resident of the Americas, and person from the United States). Alexis believes in smoothing and tidying translations to ensure her readers’ pleasure. As a translator, Alexis isn’t all about herself, but she has faith in her judgment and prioritizes her own ideas, aesthetics, and career. According to Emi, this means that Alexis violates “our sacred translation honor code”—and flagrantly, too. “She said it openly,” Emi complains: “She thought translation was also editing.” Emi, naturally, would never change a thing. She’s the model of a more old-fashioned school of translation, the translator who strives to be neither seen nor heard. Her goal is perfect fidelity to Irena’s original works—which, to Alexis, is itself a form of betrayal, since preserving meaning word by word can undermine aesthetic and emotional effect.

It’s a sign of Croft’s gift for balance that The Extinction of Irena Rey does not come down on one side or the other—not even to me, a translator very much inclined to work Alexis’s way. In my own translations, I try not to call attention to the source text’s otherness or foreignness; doing so through strategies like footnoting or italicizing words from the original language is, I think, tokenizing. Yet Emi is correct to point out that changing an original too much when translating into a world-powerful language like English can be a colonial impulse, “exactly [what] you would expect a U.S. usurper to do.” (Tellingly, this line is not footnoted, indicating Croft’s agreement, if not Alexis’s.)

Still, reluctance to change an original is often a disservice to it. Early in The Extinction of Irena Rey, Emi is shocked to discover that the author, a brilliant performer of her own prose, sings not in the “magical, mellifluous voice of an angel” but a “wobbly, frail” tone prone to breaking. In the moment, the scene seems simply to demonstrate Emi’s idol worship, but as the novel moves on, it becomes a key to the issue with Emi’s translation approach. Irena has a wonderful reading voice, but a weak, untrained singing one; so, too, she might have a wonderful Polish voice that, transposed straight into another language, needs some help.

Of course, Emi’s problems go beyond artistic philosophy. Worrying that a hookup with one of the other translators may have left her pregnant, she frets about becoming “monstrous and invaded, not even me anymore,” then adds, “Then again, I was a translator. Wasn’t not being me what I spent every day trying to achieve?” In a footnote, Alexis says, simply, “No.” This exchange contains all The Extinction of Irena Rey’s ghosts. Emi yearns to impersonate Irena, not so much to become her—hard to become your own idol—but to win her pure, total approval. Once Irena disappears, this goal, now impossible, haunts and torments Emi. She hates that Alexis can move on from Irena, since it reveals the gap between them: While Alexis wants to produce good translations of Irena’s work, Emi wants an iron grip on Irena herself.

All this may sound technical and heady for a novel, but Croft imbues the two translators’ rivalry with humor, pathos, and judicious hints of lust. The result is captivating and fun on a character level—reading Alexis’s footnotes often feels like gossiping with a friend—but it’s also a reminder to readers of a lesson that Emi needs to learn: Translation is a human act, a human art. As the novel moves toward its conclusion, Croft makes it increasingly clear that Emi does not have either her colleagues’ respect or her author’s. Her drive to translate as if she herself were absent from the text, to create perfect reproductions of Irena’s books rather than her own interpretations, likely undermines the quality of her work—and certainly skews the story she’s telling, in ways small and large, funny and sad.

The Extinction of Irena Rey is haunted by the absent Irena and by the many spirits and inhabitants of the Białowieża Forest, from the fungal networks that “coursed through the soil and stitched the plants and the trees of the forest into a united and communicating whole” to the memory of the native bison hunted to extinction by occupying Nazis. Arguably, it’s haunted by Alexis, the translator who won’t stop inserting herself. But the novel gets its emotional force from the palpable absence of Emi’s confidence, her artistic vision, her ability to pick herself over Irena. Without those things, our narrator is someone to pity: a would-be husk, a machine who wishes she had no ghost within.