My neighbors in Endwell, New York, are reasonable people. But last February, when their kids came home from Homer Brink Elementary School with a flyer about a new after-school club, they freaked out. They didn’t know what the After School Satan Club was all about, and they didn’t think Satanism had a place in their local public school.

They weren’t alone. This week in Olathe, Kansas, thousands of citizens signed an online petition to ban a new high school Satan Club, warning that it meant “satanic indoctrination” for their public school.

Both clubs were outreach efforts of the Satanic Temple, an atheist activist group founded in Salem, Massachusetts, in 2013. June Everett, director of the Satanic Temple’s After School Satan Club program, insists the clubs are not teaching children to worship Satan. Their point, rather, is to protest the use of public schools by Christian organizations. The After School Satan Clubs only open in schools that include similar after-school clubs run by conservative evangelical Christian groups. The Satan Clubs, Everett says, promise a “fun, intellectually stimulating, and non-proselytizing alternative to current religious after-school clubs.”

Not everyone has limited their opposition to complaints and petitions. In Iowa, a Christian military vet and failed congressional candidate knocked the head off a statue erected by the Satanic Temple at the state house. Though deputies charged Michael Cassidy with criminal mischief, conservative pundits like Charlie Kirk of Turning Point USA rushed to his defense, pledging $10,000 for legal fees and proclaiming, “We stand with Satan Slayer.”

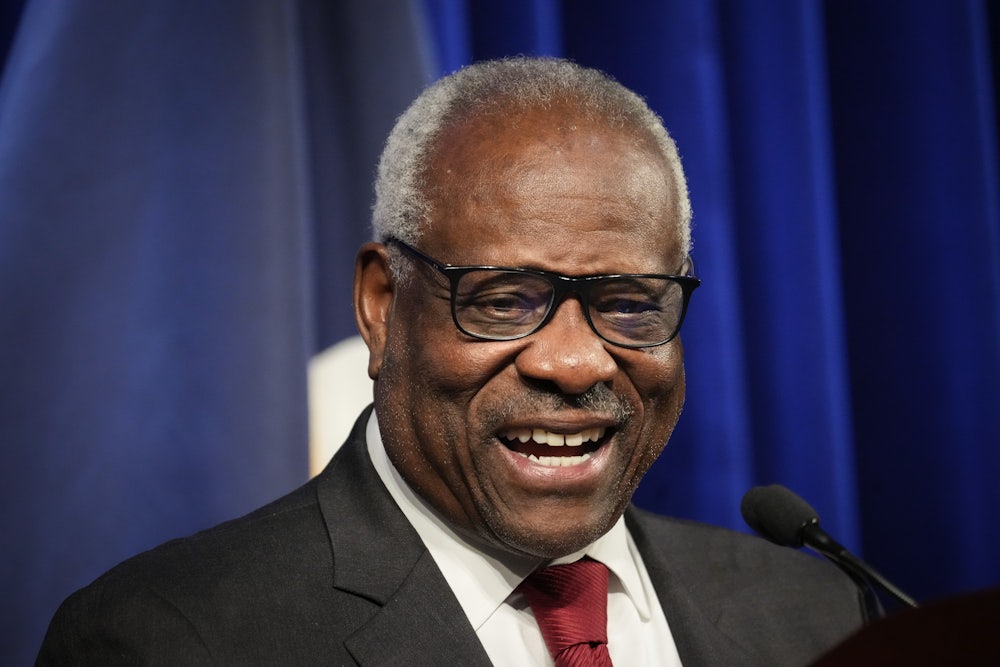

Those outraged about Satan in schools and other public buildings—reasonable and unreasonable alike—are directing their anger in the wrong direction. The people most responsible for allowing Satan into these spaces are not the leaders of the Satanic Temple. They are not even school administrators or heathen Democrats. No, the people most to blame are some of America’s most prominent conservatives—including Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. And protesters’ efforts to block Satanic clubs and displays would, if successful, undermine decades of conservative Christian activism.

So far, despite talk about them in many states, elementary school Satan clubs have been active in only four states: California, Ohio, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania. The proposed club in Kansas—the one that drew thousands of signatures to the petition to “Stop the Satan Worship Club at Olathe Northwest”—was the first to be proposed for a high school.

The clubs put school administrators in a tricky position (which is partly the point). In Hellertown, Pennsylvania, the prospect of an After School Satan Club at the local public middle school prompted a phoned-in threat.* Nervous school administrators rescinded approval for the Satan Club to meet. As the superintendent explained, the “chaos” led to “feelings of instability, anxiety and fear.”

Unfortunately for the superintendent, a Satan club has just as much right to use public school facilities as do Christian clubs. The Satanic Temple sued, and the school district eventually settled the case, agreeing to pay the organization $200,000 in legal fees and open up its facilities to a Satan club after all.

The Satanic Temple was on firm legal footing, thanks to the Supreme Court. Back in 2001, the justices heard the case Good News Club v. Milford Central School, about a conservative Christian group that wanted to run an after-school club at the district’s only K-12 school building in central New York. The district had turned down the group’s application, citing state law and district policy against the use of public facilities by religious groups, but the Supreme Court, in a 6–3 decision, ruled in the group’s favor.

Writing for the majority, Thomas concluded that the Constitution’s separation of church and state did not just justify Milford’s violation of the club’s “free speech rights.” “When Milford denied the Good News Club access to the school’s limited public forum on the ground that the Club was religious in nature, it discriminated against the Club because of its religious viewpoint,” he wrote. Thomas’s opinion did not, however, officially endorse the club’s religion, nor suggest that public schools could endorse religion.

The implications of the ruling, being somewhat narrowly written, seemed modest at the time. The Good News Club received no funding from the school district, and there were no school personnel involved. Perhaps most important, from a constitutional perspective, they also wouldn’t be conducting religious worship, only offering children, in the words of the club’s founder, “a fun time of singing songs, hearing a Bible lesson and memorizing scripture.”

But Thomas’s opinion had chipped away at the wall between church and public schools, and since then the court has opened a gaping hole. In decisions such as Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue (2020) and Carson v. Makin (2022), the justices have ruled that states cannot exclude religious schools from voucher schemes and other programs that include public funding for other types of private schools. And in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District (2022), the court ruled that a football coach at a public school can lead his players in prayer at the 50-yard line, in full view of the crowd, right after a game.

In all those cases, conservative Christians have been given more of a voice in public schools and more of a claim on public school budgets. While conservatives cheer these victories, they have been slower to notice the obvious implication of the court’s pro-religion rampage. Namely, the more gaping the hole in the wall between church and schools, the easier it is for any religion to walk through it. And that is precisely what the activists at the Satanic Temple have done. By provoking outrage, threats, and discord, the After-School Satan Clubs have unveiled Christian conservatives’ supremacist vision of religious freedom.

In case after case, from 2001 to 2022, conservative arguments have rested on one part of the First Amendment: that the government may neither prohibit the free exercise of religion nor abridge the freedom of speech. The Good News Clubs were free to speak about their religion, even in public schools, because they did so as a private group. Coach Kennedy was free to pray—even in the very public arena of a public school football game—because he was doing so as a private individual. And religious schools had a right to public school funding because they were free to exercise their religion without facing discrimination for it.

But the Satan clubs have shown the emptiness of those arguments in the real world of American public education. The First Amendment also forbids the government from ever establishing a religion, and since the 1960s that prohibition had generally kept religious activities out of public schools. Indeed, in his dissent in the Good News Club decision, Justice David Souter emphasized the point. Any “reasonable observer,” Souter noted, would think that a public school with a Christian club was endorsing the club.

The outraged parents in my town and elsewhere are proving Souter right. According to decades of conservative doctrine, a religious group in a public school is a private affair and not part of the public school itself—but these parents reasonably assume that the Satan club is part of the school and therefore subject to control by administrators. And while conservatives have long insisted that religious groups are not worshipping in schools, just speaking freely, it’s worth noting that the petition in Olathe, Kansas, is against “Satan Worship”—not “Satanic Free Speech.”

The tortured distinctions made by Thomas back in 2001, in order to rule favorably for a Christian group, are finally coming to haunt conservatives. There is no legal ambiguity here: The Satan clubs have just as much right to operate in schools as Christian ones do, and administrators are prohibited from picking favorites. That’s tough luck for parents in the grip of Satanic panic, whose only real recourse is to ask the Supreme Court to rebuild the wall between church and schools by prohibiting all religious clubs. But that would require convincing Clarence Thomas to admit he was wrong, and you might say there’s no chance in hell of that.

* An earlier version of this story misstated the location of the school.