According to recent polls, most young Democrats are profoundly unhappy with Joe Biden for backing Israel’s war in Gaza. They believe Palestinians deserve a secure, fully independent nation of their own just as Israelis do. Yet they view the president as continuing the empty rhetoric of past administrations. He favors a two-state solution but sends arms and has given unstinting support to a government that allows, even encourages, the expansion of settlements in the West Bank and denies human rights to Palestinians there. Biden’s young critics protest that the atrocities Hamas committed on October 7 cannot justify bombings that have killed thousands of Gazan civilians, deliberately or not.

If, by next November, young voters remain this demoralized and disillusioned, many may either skip the election or vote for a third-party candidate who has no chance to win. Either choice would be a grave error. In a contest sure to be as close as the last two, they could effectively award a second term to Donald Trump. The former president has already proved himself to be a vengeful autocrat—and he is entirely uncritical of Benjamin Netanyahu’s right-wing government, which ignored an intelligence report warning that Hamas was making plans for the very attack it carried out this fall.

Anger at injustice is essential to galvanizing a movement for change. Yet in their zeal, activists can also make things a whole lot worse. I was one of those leftists who made a similar mistake back in 1968, and it helped bring to power Richard Nixon, one of the worst and most consequential chief executives in American history.

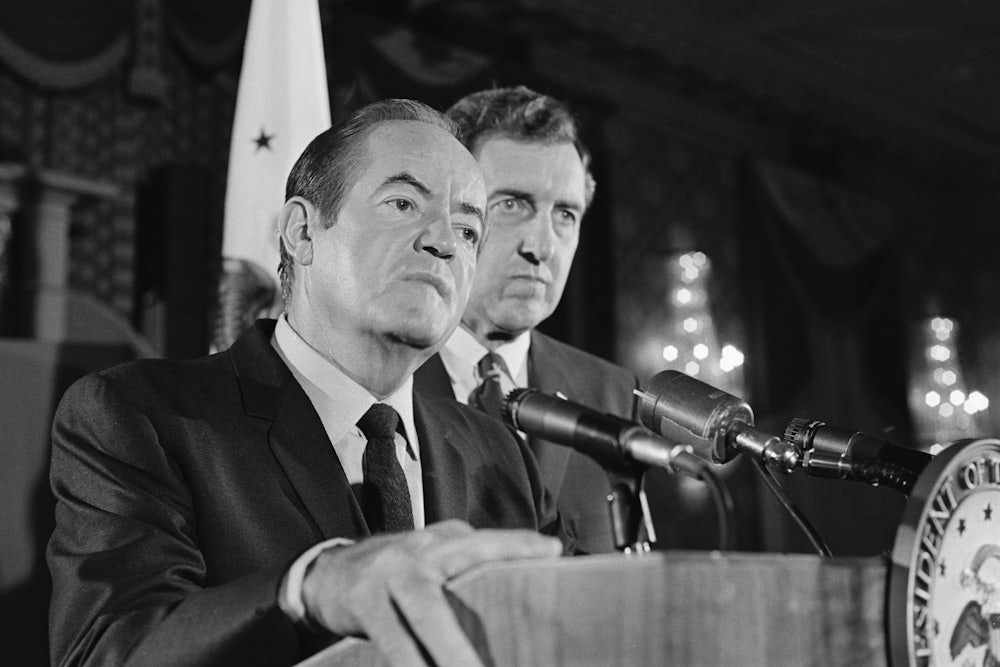

We had a strong moral case for rejecting Nixon’s opponent, Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Under the Democratic administration of President Lyndon Johnson, whom Humphrey loyally served, over half a million American troops were fighting in South Vietnam against an insurgency led by native Communists. The “body count” was horrific: More than 35,000 GIs and Marines and well over 200,000 Vietnamese soldiers and civilians on both sides of the fight had lost their lives. American planes had dropped millions of tons of bombs and herbicides that destroyed jungles and farmlands.

The argument over whether to continue the carnage split the Democrats into two hostile camps. That August, I traveled to the Democratic Convention in Chicago to protest Humphrey’s impending nomination for the White House and got arrested there. A few months later, Students for a Democratic Society, the largest left-wing group in the nation, called for a boycott of the election and backed that up with a student strike and urban rallies. “Vote with your feet, vote in the streets,” I chanted along with 4,000 other demonstrators as we marched up to the State House in Boston.

In November, Richard Nixon won a narrow victory over both Humphrey and George Wallace, the right-wing populist from Alabama who suggested that anti-war dissenters be indicted for treason. A shift of less than 88,000 votes from the Republican to the Democrat in just four states (Missouri, New Jersey, Ohio, and Alaska) would have given Humphrey a majority in the Electoral College, although he still would have lost the popular vote tally overall. It is impossible to know how many Democrats did not cast a ballot for the vice president because he defended the war eagerly and often. But as the political scientist John Mueller has written, “Their support was grudging, belittling, and too late. Others sat on their hands. The margin was enough to send Nixon to the White House.”

Of course, there are differences that matter between how Democrats disagree now and how they wrangled with one another back then. The party’s nominees in Michigan and a few other states have come to rely on the votes of Muslim Americans, who had just a marginal presence in 1968. If they refuse to vote again for Biden next year, that could well tip one or more states to the GOP.

At the same time, protesters against Humphrey’s candidacy actually had a stronger argument than do those who vow they will never vote to give Biden a second term. In 1968, the U.S. government was not merely supplying an ally with the weapons of war, Americans were doing most of the fighting and bombing. The soldiers of the National Liberation Front (known to Americans as the Viet Cong) and the North Vietnamese Army did, on occasion, target noncombatants they accused of collaborating with their foes. But neither engaged in operations as despicable as the rape, kidnapping, and mass murder of civilians carried out by Hamas that precipitated the current war. In addition, Israel today, without substantial U.S. aid, would certainly keep on fighting its Palestinian adversary. But when Congress cut back on funding the South Vietnamese military in the mid-1970s, North Vietnamese tanks were soon crashing through the gates of the Presidential Palace in Saigon.

One crucial similarity does exist between Joe Biden now and the Democrat who claimed his party’s nod for the presidency in 1968. He, like Humphrey, recognizes the peril that opponents of war inside his own party pose to his election and is taking some steps to mollify them.

A month before the 1968 contest, the vice president gave a speech in which he broke, to a degree, with the war policy he had flacked so loyally that New York Times columnist Tom Wicker quipped his subservience had earned him “a place at the White House table, just above the salt.” But in October, Humphrey promised, if elected, to stop the bombing of North Vietnam in order to speed the pace of peace negotiations. Biden wants Israel to continue to pause its Gaza offensive and stop settlers on the West Bank from displacing Palestinians from their homes. He also played a key part in brokering the release of hostages and prisoners. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin warned Israeli officials that the continued killing of civilians would “drive [Palestinians] into the arms of the enemy” and “replace a tactical victory with a strategic defeat.”

If the aim of Biden’s critics is to keep pressuring him to revive the two-state solution, they will cover themselves with virtue. But to continue to oppose his reelection unless he denounces and breaks entirely with Israel risks handing state power to a Republican who will have no reason to bend in even the slightest way to their pressure.

I remain as committed to the ideals of the left as I was back in 1968. But back then, in my small, disruptive fashion, I may have helped elect a president who ended the era when liberals dominated American politics, enacting policies like the Civil Rights Act and Medicare that benefit tens of millions of people. Under Richard Nixon, the nation began to move rightward, a shift from which we are still struggling to recover. Before the Watergate scandal brought him down, he also took four long years to withdraw U.S. troops from Vietnam, after another 20,000 or so U.S. soldiers and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians had died.

Donald Trump may not embroil the nation in a long and bloody foreign conflict. But he’ll hand Ukraine to Putin, and he’ll give Israel a total free hand to kill as many Palestinians as it can. And here at home, Trump has already vowed to wage a war against “the Communists, Marxists, fascists and the radical left thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our country.” Such invective most definitely includes young Americans who sympathize with the Palestinian cause. To support the Democrat who runs against him next year should not be shrugged off as voting for a lesser evil. It will be a necessary choice to preserve what, in his final speech, Martin Luther King Jr. called “the right to protest for right” that is so vital to whatever “greatness” our nation possesses.

Michael Kazin’s latest book is What It Took to Win: A History of the Democratic Party. He teaches history at Georgetown University.