The 60-second TV spot begins with a series of brief shots: a lobster boat setting out just after dawn, a man exiting a taxi at a crowded downtown intersection, a farmer on his tractor, a boy on his bicycle. Accompanying the gauzy imagery is soothing dentist-office music and a confident male voice whose intonations suggest safety and comfort.

“It’s morning again in America,” the narrator says. “Today more men and women will go to work than ever before in our country’s history.” We are visually transported to a small-town wedding with smiles everywhere. “Today 5,500 couples will be married, and with inflation at less than half of what it was just last year, they can look forward with confidence to the future.” There is a flash of the Capitol lit up at night before the ad lovingly dwells on a series of flags being slowly hoisted in suburban backyards. “It’s morning again in America, and under the leadership of President Biden, our country is prouder and stronger and better. Why would we ever want to return to where we were less than three short years ago?”

That commercial doesn’t exist.

In fact, aside from changing a few statistics and cutting a single sentence about interest rates, it is lifted word for word from a 1984 Ronald Reagan campaign spot. That Reagan ad, which visually evokes the world of 1950s sitcoms, is widely regarded as the most memorable lump-in-your-throat political pitch in history.

Nearly four decades have passed since Reagan won reelection in a 49-state landslide over Walter Mondale. But it is virtually certain that Joe Biden (who ran more than 20 percentage points ahead of Mondale in winning his third Senate term from Delaware) recalls that ad campaign. And so do many of the president’s senior advisers whose political memories predate the Reagan years.

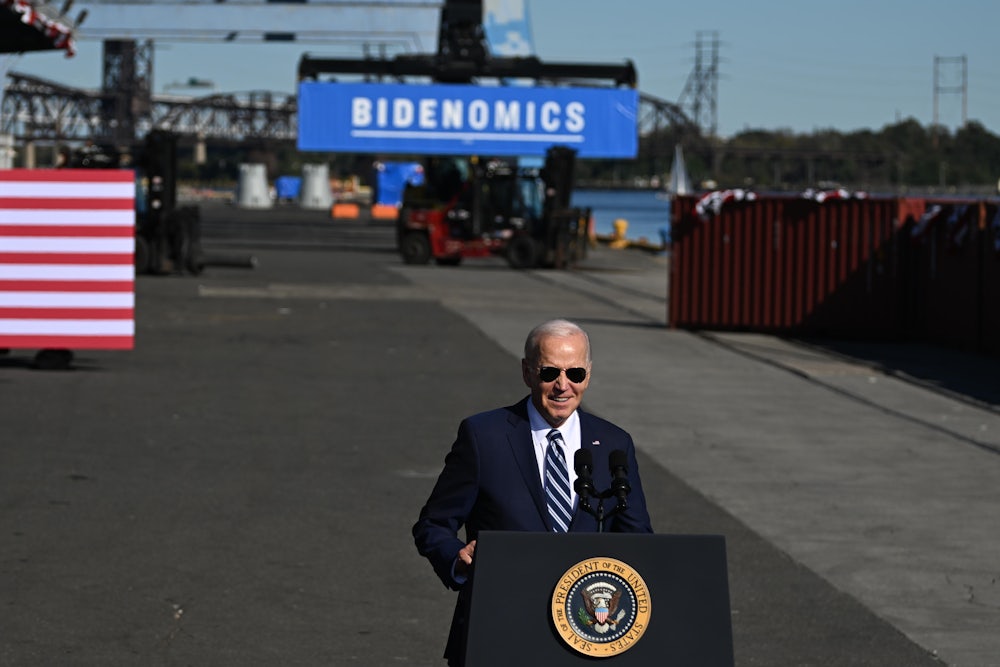

When Biden enthusiastically embraced the term “Bidenomics” back in June, the political success of “Reaganomics” clearly was part of the inspiration. Political linguist William Safire pointed out during the Clinton years that the “omics” suffix works best for presidents whose last names end in n. Biden, of course, is lucky enough to have the right final consonant. But what the president and his 2024 campaign team have consistently failed to appreciate is how much the economic universe has changed since the 1980s.

The result was an unforced political error. After brandishing the term 101 times over the past five months, Biden has virtually abandoned “Bidenomics.” It is easy to understand why. A Gallup Poll, released this week, found that only 32 percent of the voters approve of the president’s handling of the economy, close to Biden’s lowest ebb last year.

But why was Biden and his team gulled into believing that “Bidenomics” would ever be a political asset in a difficult reelection campaign?

The most logical explanation is that by Reagan-in-1984 standards, this is the greatest economy since John Maynard Keynes took his first course at Cambridge in the dismal science. With the unemployment rate consistently under 4 percent and healthy job growth continuing unabated, Biden and the Federal Reserve appear to have pulled off a hard-to-achieve soft landing for the economy. Inflation—the most frightening number for the Biden White House—has plunged to a seemingly manageable 3.2 percent. Wages are growing and have, over the course of this year, begun to outpace inflation. And the stock market, which is the only measure that Donald Trump ever cared about, is up nearly 15 percent since the Former Guy left office.

The “misery index” was the vogue economic concept during the 1970s and 1980s. It is simply the combination of the unemployment and the inflation rates—and Jimmy Carter successfully brandished it against Jerry Ford in 1976. Reagan mocked the Democrats in his 1984 acceptance speech at the Dallas convention, “Four years ago, in the 1980 election, they didn’t mention the misery index, possibly because it was then over 20 percent. And do you know something? They won’t mention it in this election either. It’s down to 11.6 and dropping.”

Under Joe Biden, the current misery index is down to just 7.1 percent. So why then are voters so miserable?

In 1984, the nation had been grappling with inflation rates higher than 3 percent annually since Lyndon Johnson was in the White House. For 15 years, Americans had grown inured to picking up a can of Campbell’s soup and discovering stickers with three different prices on it, each one higher than the last. That was economic life when Jerry Ford was peddling WIN (Whip Inflation Now) buttons in 1974 and when Jimmy Carter ran for reelection amid a 13.5 percent inflation rate six years later.

The political problem for Biden is that no voter younger than, say, 55 years old remembers this prior inflation. Many Democrats grouse that the news media only highlights bad economic news for Biden. While headline writers do seem to detect a mythical recession more often than conspiracy theorists spot UFOs, inflation is treated as news because, well, it’s still new. Prices may have stopped rising, but in most categories, they have not retreated to their pre-Biden levels. Of course, that was also the case in 1984. But back then, voters didn’t long for anything more than price stability at current levels.

A low unemployment rate can be politically tricky. Workers who snag a well-paying job in flush times believe that their success is solely due to their innate talents and their charm during the job interview. But anyone who loses a job in an economic downturn is eager to blame the current president for their misfortune.

There have been other major changes over the past four decades in how voters perceive the economy.

Income inequality was a minor political motif in 1984. Mondale flicked at the issue in his convention speech (“Today, the rich are better off. But working Americans are worse off, and the middle class is standing on a trap door”) but devoted far more political energy to outlining his plans to reduce the deficit. During the 1980s, younger voters did not fear that student loans would be a lifetime burden. And while current mortgage rates are much lower than they were under Reagan (14 percent on Election Day in 1984), the cost of borrowing for a home has doubled since Biden took office.

Many in Biden-land are wedded to the fallacy that with better messaging and an onslaught of Biden TV spots, voters can be shaken from their conviction that these are dire economic times. But, in reality, you can’t convince anyone that they’ve never had it so good when they’re feeling beleaguered. Personal feelings (including a lingering sour mood from the pandemic) define the economy for most voters—and not an array of statistics about comparative inflation and jobless rates.

There is scant hope that the president can sell the argument that it’s morning again in America. In fact, Biden and the Democrats will be lucky if voters cast their 2024 ballots believing that it’s mid-afternoon.