In the winter of 1983, I was 25 and working at The New York Times as an editor on the op-ed page. In those days the Times’ staff for editing outside daily commentary was tiny—four people—and I was responsible for most of the pieces on domestic policy, then, as now, my principal professional interest. The pay was handsome ($110,000 in today’s dollars), and I loved living in New York City—then, as now, a powerful magnet for recent college graduates. It was a dream job, and my parents relished the bragging rights of having a son at the Gray Lady. But there was a better job, in Washington, D.C., working as an editor and writer at less than one-quarter the pay for a magazine most people had never heard of. I grabbed it.

The magazine was The Washington Monthly, and the editor in chief was Charles Peters, who died on Thanksgiving, a few weeks shy of his 97th birthday. Charlie was (per the late Russell Baker, the Pulitzer Prize–winning columnist and author) “a great editor in an age that’s not producing great editors,” even though he never took pencil to a manuscript (because no one except his amanuensis, Carol Trueblood, could read his handwriting). Charlie talked instead, and exhorted, and, when he got really excited, jumped up and down pounding his right fist into his left hand, in a ritual that came to be mythologized by Monthly editors as “the rain dance.” He was a passionate idealist, a New Deal Democrat who believed that an activist federal government had done great things in the past and could do great things in the future. But it was very much in need of a Lorena Hickock, whom history remembers chiefly as Eleanor Roosevelt’s probable paramour, but whom Charlie remembered as Harry Hopkins’s eyes and ears traveling the country and writing dispatches about the effects of the Great Depression and Roosevelt’s New Deal programs on ordinary Americans, later collected in the classic volume One Third of a Nation.

Hickock was one of many distinguished Washington Monthly writers who never actually wrote for the Monthly, in Hickock’s case because she died before it was founded. By this I mean writers who approached the topic of government in much the same spirit of intellectual and emotional engagement that Charlie wanted in Monthly pieces. Another was Lytton Strachey (1880–1932), whose profile of Florence Nightingale in Eminent Victorians revealed that the “lady with the lamp,” far from being some ethereal saint, had been a ferocious bureaucratic infighter who’d saved British lives by dragging its army, kicking and screaming, into modern methods of sanitation. Another was Robert Caro, whose The Power Broker demonstrated the extreme dangers of unaccountable public authorities that amass great power. I was astonished one day in 1984 or so when, walking into the Monthly’s dingy offices on Connecticut Avenue, I encountered Caro, already a legend (the first volume of his Lyndon Johnson biography just recently published to ecstatic reviews), perched precariously atop a stack of cardboard boxes in what passed for our reception area (there was no receptionist), waiting uncomplainingly to meet Charlie for lunch. “You work for a very interesting man,” he told me.

As a young state representative in West Virginia, Charlie ran John F. Kennedy’s 1960 presidential campaign there. That brought him to Washington, where he joined the Peace Corps’s extraordinary founding team, led by Sargent Shriver and including Jay Rockefeller, Harris Wofford, Bill Moyers, William Haddad, and Frank Mankiewicz. Shriver decided that the Peace Corps needed an internal department of evaluation to make sure its programs met the needs of host countries and, if they didn’t, to fix them. Charlie quickly concluded that government employees were too circumspect to perform this task properly, so he started hiring professional journalists like Baker, Calvin Trillin, and Murray Kempton on a freelance basis. He quickly realized that all agencies of the federal government could be evaluated along the lines that Shriver had proposed, and in 1969 he created The Washington Monthly to do that.

At first Charlie ran the Monthly like a normal magazine, with professional salaries and name writers and all the other conventional accoutrements. That quickly sent the Monthly into Chapter 11. So, drawing on skills he’d developed when, right out of Columbia, he’d managed a shoestring theatrical troupe, Charlie cut expenses to the bone. Into the 1990s, and perhaps longer, he paid himself only $24,000 and his young editors, who came in for two-year stints near the start of their careers, $8,400. (“Charlie thinks,” Monthly editor Jonathan Alter told me when I applied for a job there, “he may soon be able to pay in the five figures.” It never happened.) Working for a pittance (living largely off his wife Beth’s less-than-grand salary as a schoolteacher) was the price Charlie paid to have the life he wanted, and he paid it gladly. Unlike most small magazines of opinion, the Monthly did not have a wealthy owner; instead, Charlie had a revolving group of small investors to whom he turned in times of need, none of them expecting any return, which was good because they ended up owning well in excess of 100 percent of the magazine. I should here mention that Charlie’s favorite movie was Mel Brooks’s The Producers, whose two main characters go to jail for using that same maneuver to sell shares in a Broadway show that becomes an accidental hit.

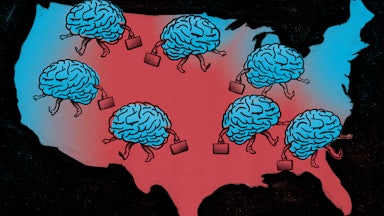

Nothing like that ever happened to the Monthly. It never acquired much of a circulation, even in Washington, where to this day a surprising number of government insiders have never heard of it (though not the better sort). But it caught the attention of candidate Jimmy Carter, who hired Monthly editor James Fallows as chief White House speechwriter. Its principal influence was within the journalism community, as Charlie’s employees infiltrated The New York Times, The Atlantic, Newsweek, and, yes, The New Republic, carrying with them an infectious fascination with the tools of American governance.

Charlie called his creed neoliberalism, which creates some retrospective confusion today because that same word is now used to describe the market fundamentalism embraced by President Ronald Reagan and the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, neither of whom the Monthly had much use for. Charlie was anything but a market fundamentalist. He respected what capitalism could do, and occasionally he found uses for it in meeting public policy ends, but he also believed, like his hero FDR, that business warranted strict regulation and more progressive taxation. He was wary of the public-private partnerships that came into vogue in the 1980s, and, for instance, he thought the quasi-privatization of the Post Office had been a terrible mistake; he wanted it restored to political control.

At one point while I was working for Charlie he penned a “Neo-Liberal’s Manifesto” for The Washington Post that declared common cause with Gary Hart, Bill Bradley, and Paul Tsongas and attempted to lay down a common set of policies. These have not aged well, and they did not reflect Charlie’s true strength, which was to free himself from preconceived ideas of all sorts and embrace FDR’s spirit of pragmatic experimentation to serve the common good. He was repelled by President Ronald Reagan’s declaration that “government is the problem” and by President Bill Clinton’s subsequent fatuous echo, “the era of big government is over.” He saw government as a powerful tool to improve people’s lives, and he believed it was every citizen’s duty to pitch in and help. His final book, published when he was 90, was titled We Do Our Part, which was the slogan of FDR’s National Recovery Administration.

Charlie was a fine writer; his best book, Five Days in Philadelphia, argued persuasively that the Republican convention of 1940, in bypassing the GOP’s isolationist establishment and instead nominating Wendell Willkie, played a crucial role in Hitler’s defeat. But he spoke most powerfully through the journalists he trained: Taylor Branch, biographer of Martin Luther King; Fallows and Nicholas Lemann at Texas Monthly and later The Atlantic (and, still later for Lemann, The New Yorker); Gregg Easterbrook at The Atlantic; Katherine Boo at The New Yorker; Paul Glastris, who succeeded Charlie as editor of the Monthly; Michael Kinsley, Walter Shapiro, Mickey Kaus, and myself at The New Republic; Jason DeParle, James Bennet, and Michelle Cottle at The New York Times; David Ignatius, foreign affairs columnist at The Washington Post; and too many others to name. No less robust is the Monthly’s roster of former interns, including John Harris, co-founder of Politico; Ezra Klein, the influential columnist and podcaster for The New York Times; Michael Waldman, president of the Brennan Center; and Douglas Jehl, international editor of The Washington Post. Under Glastris, the Monthly continues to send journalists out into the world who are engrossed in the unglamorous nuts and bolts of legislating and regulating.

When Charlie retired from the Monthly editorship, he started a nonprofit called Understanding Government to fund Washington Monthly–style investigations of government bureaucracy and how it could be made to work better. It performed good work for about 15 years before shutting its doors. One of Charlie’s frustrations, though, was that almost all those who applied for grants were academics rather than journalists. Charlie had no particular objection to funding academic studies, but he wanted the Monthly’s journalistic approach to covering the federal government to go viral, as we say today. That never happened. The nooks and crannies of government that the Monthly covers get multipage investigations in the Post or the Times when things go egregiously wrong, and more routine coverage in the trade press and in Politico Pro, the trade arm of Politico, where I worked for several years as an editor. But there is still very little in between—ongoing critical coverage aimed at improving government performance at the ground level, pitched not to government professionals but to ordinary citizens who favor more effective governance. People today want to hate government, or to defend it unquestioningly. But in a properly working democracy, when we look at government we’re looking at ourselves. When we don’t like what we see, it’s up to us to set it right. That’s what Charlie Peters taught me and many others.