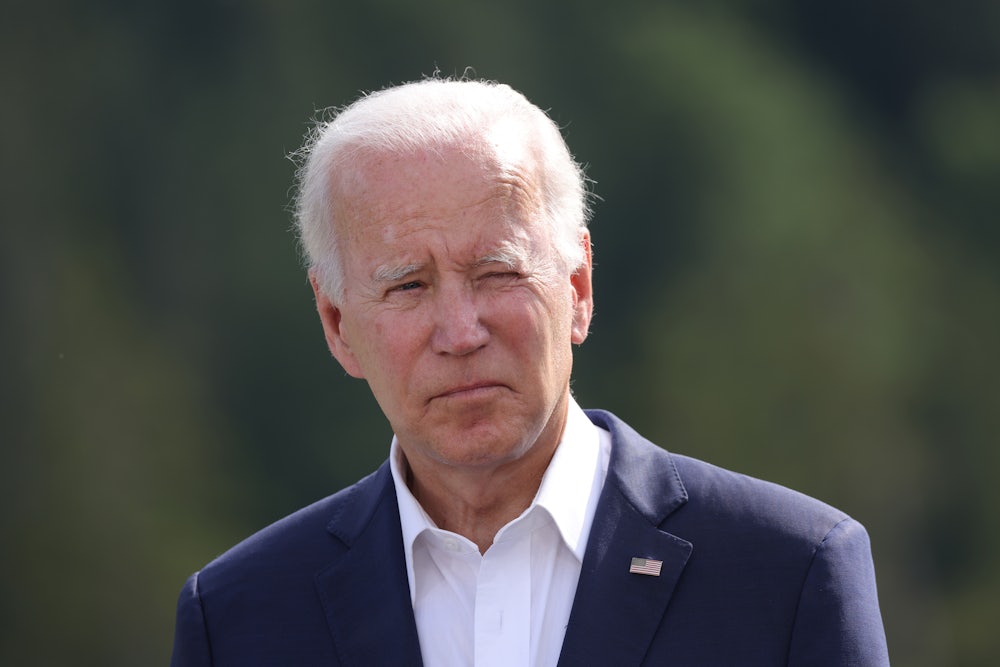

Panicked Democrats, vibrating with anxiety over the polls, continue to nurture an unlikely fantasy: Joe Biden looks at his family across the Thanksgiving table on Nantucket and says with a weary sigh, “I can’t do this for another five years. I’ve tried my best. But I just don’t have the stamina to keep going through 2028.”

Nothing in the president’s makeup suggests that he would abruptly jettison his reelection campaign, especially since Hamas’s attack on Israel has further convinced Biden that he has become the world’s Indispensable Man. Every sign emanating from his inner circle and reelection campaign suggests a stubborn refusal to even acknowledge his growing legion of Democratic doubters. But even if Biden were to accept the truth embedded in the polls, as Harry Truman did when he bowed out in 1952, the subsequent multicandidate scramble for the Democratic nomination would create as many (if not more) political problems as it would solve. In fact, were Biden to suddenly abandon his reelection campaign, the clichéd news magazine headline from the 1990s would be apt: “Now for the Hard Part.”

It is easy to get caught up in questions of logistics since the filing deadlines have already passed for the Democratic Party’s first two authorized primaries: South Carolina (February 3) and Nevada (February 6). By the end of November, California (March 5) will have closed the books on its primary, and the deadline for Michigan (February 27) is in early December. But barring a divisive contested Democratic convention in Chicago, any Biden delegates chosen in these early states would presumably rally behind the leading candidate in the name of party unity.

What about money, which a deep-pocketed presidential candidate once described as “the most reliable friend you can have in American politics”?

In a suddenly wide-open Democratic presidential race, well-known candidates (particularly big-state governors like Gavin Newsom) will have more than their share of reliable friends. Powered partly by online giving, presidential contenders raised more than $1.2 billion for the 2020 Democratic primaries—and that doesn’t count lavish self-funders Michael Bloomberg and Tom Steyer. The effective collapse of campaign finance rules also means that Democratic super PAC billionaires, dreaming of a cushy European ambassadorship or a minor Cabinet post, would also play a major role in any non-Biden 2024 nomination fight. True, a truncated primary season would make it impossible for an out-of-nowhere candidate to have enough time to catch fire in the early states like Pete Buttigieg in 2020 or a former Georgia governor named Jimmy Carter in 1976.

If Biden dropped out at any point before the Democratic convention, it is virtually certain there would be a contested battle for the nomination. That’s the way politics works—and not even a Biden endorsement of Kamala Harris would change that. Vice President Richard Nixon in 1960 is the last nonincumbent to be granted a presidential nomination without a fight. And even Nixon had to mollify New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller. Since then, three sitting vice presidents have faced spirited challenges: Hubert Humphrey at the tempestuous 1968 convention, George H.W. Bush in 1988, and Al Gore in 2000.

Maybe things might be different if Harris were universally beloved in the party and had an unequivocal edge on Donald Trump in the polls. Neither is the case unless you insist on cherry-picking poll numbers. The hope would be that the specter of an unfettered Trump in the White House—trying to imprison his enemies, quash dissent, and round up immigrants without papers—would temper the likely intraparty discord triggered by a Biden withdrawal. But, alas, the modern history of the Democratic Party screams, “Don’t bet on it.”

As president, Biden has papered over many of the ideological fissures in the party by being far more ambitious in his legislative agenda than his prior moderate reputation might have suggested. But if the 81 year-old (as of today) Biden opted out of a second term based on age, presumably that would also leave Bernie Sanders (82) and maybe Elizabeth Warren (74) on the sidelines.* An unanswered question under such a scenario: Who, if anyone, would emerge as the left-wing favorite in the primaries? There is no natural successor to Sanders or Warren being bandied about as a break-in-case-of-emergency option should Biden withdraw. Left-wing California Representative Ro Khanna has been making all the right moves with frequent visits to early states like South Carolina and New Hampshire. But he is far too little known to take off in a 2024 campaign with a very short runway.

If Biden announced on the Monday after Thanksgiving that he would be retiring, it would give 2024 presidential contenders fewer than 100 days to declare their candidacies and define their image before 14 states pick delegates on Super Tuesday, March 5. And 11 other states will be holding Democratic primaries later in March.

Organizing a campaign and raising the money at that pace would be gruelling enough. But candidates would also face high-intensity scrutiny from the media and the voters without any benefit from a learning curve. It would be the equivalent of opening a musical on Broadway without a single tryout and just three days of rehearsals.

Unless you have run for president or witnessed a campaign close up, you have no idea how daunting it is. A statewide campaign, even against fierce Republican opposition, offers only limited preparation. And it is even harder if you are coming out of a one-party state like California or Illinois. Regular appearances on Sunday morning shows or a few tough interviews on Fox News are barely comparable to spring training, let alone the World Series. Even a naturally charismatic candidate like Barack Obama seemed lost in the wilderness in the fall of 2007 until he belatedly found his footing against Hillary Clinton. The leading names being bandied about as theoretical Biden replacements, moreover, are all governors who have not run for president before: Newsom, Illinois’s J.B. Pritzker, and Michigan’s Gretchen Whitmer. Although all three have done a major chunk of cable TV hits during Biden’s three years in office, many Democratic primary voters would not recognize any of them if they shared a small elevator.

Those who have been watching the Republican debates (not necessarily a recommended activity) probably will have noticed that, in a technical sense, both Nikki Haley and Ron DeSantis have grown more adept over the last three months. That is the learning curve at work. A bygone example illustrates this point for me. Gary Hart—the Democratic front-runner who had been driven from the 1988 nomination fight by a sex scandal—returned to the fray in December 1987 after seven months on the sidelines. The rust showed. Normally a sharp debater, Hart was fuzzy and imprecise when he faced off against his Democratic rivals (who had been sparring for months) at the University of New Hampshire in January 1988.

Even a globe-trotting governor like Newsom, who visited China last month, would be ill prepared for the full range of queries that would be immediately hurled at him as a presidential candidate—hourly questions about a cease-fire based on the latest glimmers of news from Gaza, repeated inquiries about the best Democratic strategy on Capitol Hill to keep the government open, and never-ending queries about how to finance proposed new government programs. Senators obviously have a more national and international focus than governors, but such would-be candidates as Georgia’s Raphael Warnock or Connecticut’s Chris Murphy would also need time to build their repertoire of stock answers.

Obviously, those candidates who ran for the nomination in 2020 would have a built-in advantage in a too-much-too-soon Democratic primary season. But Harris has gone from flaming out in the presidential race before a single primary vote was cast to struggling to find her footing as the vice president. Remember, she is currently running in most polls at roughly the same level against Trump as Biden. Buttigieg, who narrowly won the 2020 Iowa caucuses, has not been as dominant a political figure as might have been expected as Biden’s transportation secretary. Despite a strong run as a surrogate, particularly on Fox News, he has faded from view after being criticized for a tardy response to the train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio. Amy Klobuchar, who outperformed expectations in the 2020 New Hampshire primary, and Cory Booker, who never got traction in the primaries, are senators who have struggled to raise money for a national campaign. And neither of them has been at the center of the action in the Senate during the Biden years or done much to enhance a sense of inevitability as a future presidential contender.

Any of these candidates could excel in a post-Biden presidential campaign. But with a truncated primary schedule, there will almost inevitably be embarrassing stumbles and setbacks on the way to standing victorious on the convention stage in Chicago. Since the media is normally sycophantic to candidates on the way up (and vicious on the way down), a winning presidential candidate is apt to be bathed in a hero narrative at least until he or she accepts the nomination. But a replacement candidate forced to plunge into the middle of a campaign without a rehearsal period may appear to the voters as a more flawed option than Biden does today.

By my reckoning, Biden made a heedless mistake by not bowing out of the 2024 presidential race last spring, knowing that his age would be a political liability. Such a springtime 2023 decision would have given his Democratic successor ample time to run a winning and hopefully inspiring primary campaign.

Instead, Biden chose to defy Father Time. And at this point, Biden—despite his obvious flaws as a candidate—is probably the Democrats’ best option for president against Trump. For in politics, it gets late early. And it is, sadly, too late for a compelling Biden replacement.

* This article originally misstated Biden’s age.