When Representative Nancy Mace was elected in 2020, she defeated the Democratic incumbent by fewer than 5,400 votes, or one percentage point. Two years later, that razor-thin margin was a thing of the past—she sailed to reelection by 14 percent.

How did Mace pull it off? The shift in partisan leaning in South Carolina’s 1st congressional district certainly helped. The startling difference in her winning margin came via redistricting: After the 2020 census, the Republican state legislature redrew her seat to be safer for Republicans. But Mace could once again face a challenging road to reelection, as the Supreme Court has taken up a case that will determine whether the legislature racially gerrymandered the district to favor Republicans by moving Black voters, who often support Democrats, to another congressional district. The court heard arguments for the case, Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, on Wednesday.

Given Republicans’ slim majority in the House of Representatives, any congressional seat that is up for grabs becomes a potential pickup for Democrats in their quest to retake the House. If the Supreme Court rules that the districts in question should be redrawn, the ramifications will echo far beyond South Carolina.

“We’re in a district [that] three cycles ago a Democrat was in before the gerrymandering,” said Michael B. Moore, a Democrat running against Mace. “Potentially, we could be the seat that helps Democrats regain control of the House again.”

There’s no question that South Carolina’s 1st congressional district was gerrymandered. The issue before the Supreme Court is whether it was redrawn with primarily racial or partisan considerations in mind. Court precedent dictates that racial gerrymandering is illegal, but redrawing a district to benefit a particular party is permissible.

The district, drawn after the 2020 census, divided communities in Charleston County, placing key suburbs under the purview of Representative Jim Clyburn, the sole Democrat in the South Carolina congressional delegation. Roughly 30,000 Black voters were moved out of the 1st district and into Clyburn’s.

In January, after a case was brought by the South Carolina chapter of the NAACP and a Black voter, three federal judges found that the gerrymander amounted to “bleaching” the district and racially discriminated against Black voters. The judges determined that, in order to create a solid Republican district, GOP legislators drew the district to keep the Black voting-age population at around 17 percent, and ordered a redraw of the map. The court wrote that reducing the percentage of Black voters “was no easy task and was effectively impossible without the gerrymandering of the African American population of Charleston County.”

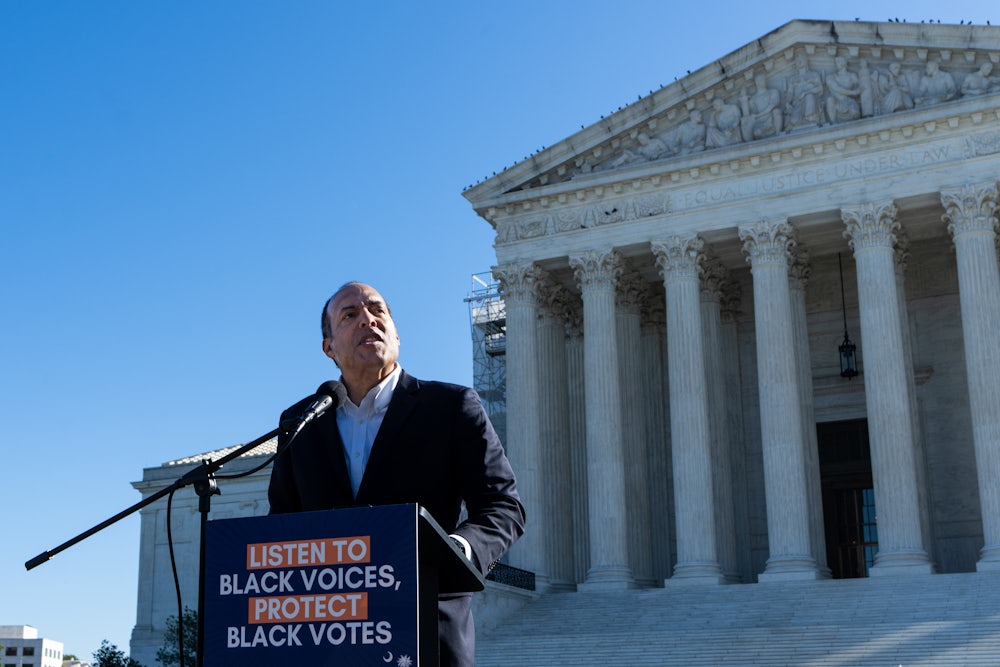

This case is personal for Moore, who is a descendant of Robert Smalls, one of the first Black congressmen to serve after the Civil War. There is some symmetry in the history—Smalls was elected to a different district in the mid-1880s after his seat was gerrymandered. Moore is quick to note that he is “fighting a very similar fight” to his grandfather, roughly 150 years later. “There is a lot about what’s happening now in the country that, for those of us who are attuned to history and have a sense about Reconstruction, at least gives us pause and concern about where we are,” Moore told me in an interview, hours after he spoke at a rally in front of the Supreme Court.

But GOP legislators insist that the redistricting was not motivated by racial discrimination, but rather by partisan concerns. Republican state lawmakers quickly appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that the South Carolina–based judges had assumed the legislature acted in bad faith. Both sides have requested the Supreme Court to make a determination by the end of the year, so that a correct map will be in place for the 2024 election.

Mace’s future may depend on the Supreme Court’s decision. If the court rules in favor of the GOP legislators, her reelection is far more likely. Should the court rule otherwise, Mace’s challenge becomes steeper.

Mace’s role as one of eight Republican representatives to vote to oust Speaker Kevin McCarthy could also factor in to her political future. Mace had garnered a reputation for her willingness to challenge the party line, including occasional criticism of former President Donald Trump. But those moderate credentials have shifted somewhat since she was reelected to a district drawn to be more conservative.

“Now she’s such a wild card, wearing a scarlet letter, that Democrats can make the case that she’s more of an obstructionist who’s hanging out with Steve Bannon than a maverick who’s willing to buck Trump,” said Dave Wasserman, an elections analyst at the Cook Political Report. Mace recently appeared on the podcast of Bannon, a former Trump adviser, with Representative Matt Gaetz—two years after she voted to refer a criminal contempt case against Bannon to the Justice Department.

“Despite talking, at times, a moderate game, she has proven to be one of the more extreme members of Congress,” Moore said.

Supporters of the South Carolina NAACP were heartened by the Supreme Court’s decision this year to order Alabama to redraw its congressional map to account for its significant Black population. However, that decision was based on the justices’ interpretation of the Voting Rights Act, whereas the case coming from South Carolina is founded in an entirely different argument, maintaining that Black voters were discriminated against under the equal protections clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This means that the justices may not be beholden to the same precedent. Indeed, the conservative justices on the Supreme Court appeared skeptical of the plaintiff’s case during oral arguments on Wednesday, where they noted that the challengers did not provide an alternative map.

Wasserman says that Mace could be feeling “cautiously optimistic” about the outcome of the Supreme Court case. Whereas Mace faced a Trumpian primary challenger in 2022, she has stronger bona fides with the right flank of her voter base. “In terms of her place in the Republican coalition, she’s been all over the map. She can make arguments to all kinds of Republicans as to why they should vote for her,” said Wasserman. “If the Supreme Court upholds the lines, she’s only going to have to worry about a primary.”

In a statement, Mace’s office indicated that she is prepared for any ruling by the Supreme Court. “Congresswoman Mace has consistently been an independent voice for the Lowcountry since she took office. She will continue to deliver results for South Carolina no matter what the district looks like,” spokesperson Will Hampton said.

Still, Moore said that his campaign is not relying on the outcome of the Supreme Court case. He highlighted his campaign’s strong fundraising in the first and second quarters of the year as evidence of his efforts, and chance for success, outside of what the Supreme Court decides.

“We’ve developed a plan without regard to whatever the Supreme Court does,” said Moore. “I care deeply about how the Supreme Court rules in this, but we are working hard, and we believe we can win either way.”