The “Kennan Sweepstakes,” they called it in the early 1990s. Decades earlier, the diplomat George Kennan had won lasting renown (and lifelong self-torture) with his writings at the Cold War’s outset that outlined the nature of the Soviet threat to the United States and prescribed a vague strategy to counter it. Now, as the Soviet Union relaxed its grip on Central Europe and then imploded, leading thinkers, government officials, and policy wonks scrambled to define the nature of this new age in foreign affairs (ideally via a catchy term like Kennan’s “containment”).

Francis Fukuyama’s essay on “The End of History?” in The National Interest is only the best-remembered of the ideas that were tossed around. The journalist Charles Krauthammer identified a “unipolar moment” where peace could only be assured by the United States having “the strength and will to lead a unipolar world, unashamedly laying down the rules of world order and being prepared to enforce them.” With less literary felicity, the political scientist John Mearsheimer foresaw a Europe dissolving into chaos and war as “Germany, France, Britain, and perhaps Italy will assume major-power status” and battle for power. Leaders like Mikhail Gorbachev, George H.W. Bush, and Joe Biden called for a renewed emphasis on cooperation through the United Nations and anticipated reduced military conflict, while, in 1993, President Bill Clinton floated “democratic enlargement” as his guidepost.

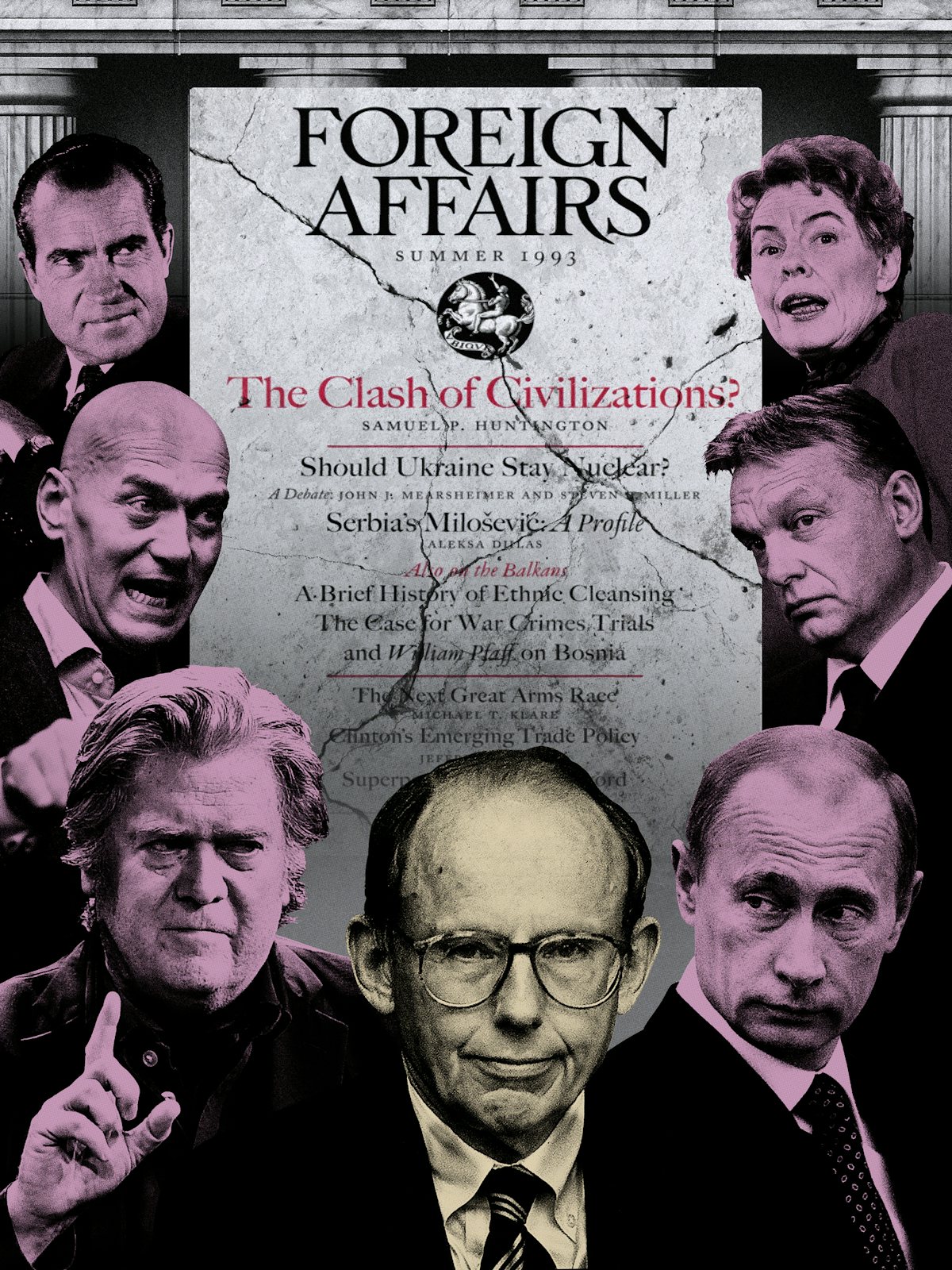

This was the context when Samuel Huntington injected his famous ideas into public consciousness 30 years ago. A 1993 Foreign Affairs essay he expanded into a bestselling book with a slightly different title three years later, “The Clash of Civilizations?” argued that the source of conflict in the world in the coming decades would not be primarily economic or ideological, as it had been. Rather, cultural issues would rise to the forefront of the international arena in unprecedented ways. “The clash of civilizations will dominate global politics,” he wrote, making a bold prediction despite the question mark in the essay’s title. Countries should be grouped together not by their political systems or levels of economic development but by civilizational belonging and be “differentiated from each other by history, language, culture, tradition and, most important, religion.” Nation-states would still be the predominant actors in the world, but they would battle less over geopolitics as it had been traditionally understood since the seventeenth century than over resurging cultural and religious identities. “The next world war, if there is one, will be a war between civilizations.”

Huntington clarified that he wasn’t eager to see a clash of civilizations—he advised Western policymakers to be cognizant of the tremendous sensitivities around cultural issues so they would avoid imposing their values on non-Western peoples and refrain from interfering in their affairs. “The reason he wanted to put the question mark is that he didn’t want the world to go down this direction; he wanted there to be cooperation among civilizations—reconciliation and dialogue,” recalled his one-time doctoral student Fareed Zakaria, who commissioned Huntington’s article as managing editor of Foreign Affairs. That call for peaceful collaboration between civilizations was largely lost in the subsequent furor over the article, although calls for cooperation were admittedly not the bulk of the essay or the book but merely a small component.

Huntington died in 2008, but the argument he ignited has long outlasted him. The debate over the clash has not abated, 30 years on. It is still common each month to read in the media about a civilizational clash or hear elected officials and intellectuals reference the catchphrase, as a random sample indicates. “The Theory Is Alive,” the Indian version of The Telegraph declared in April. In June, Morocco’s King Mohammed VI said that the world was witnessing not a clash of civilizations but a “clash of ignorances.” Chinese leaders recently proposed an “equality of civilizations” in place of the West’s clash, according to The Economist, which reported a diplomat lamenting that “the antiquated thesis of a ‘clash of civilisations’ is resurfacing.”

Indeed, Huntington’s argument is so antiquated that it has already gone through several afterlives and been resurrected, like a horror movie villain. As the twentieth century ended and liberal capitalist democracy seemed unrivaled, it appeared as though The Clash of Civilizations was unduly pessimistic and perhaps irrelevant to the international arena. But after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Huntington’s book became a bestseller for a second time, as conservatives across the United States and Europe cited its arguments for why Islam was fundamentally incompatible with Western society. When refugees from Syria and elsewhere in the Middle East attempted to find stability in white-majority countries, Huntington’s ideas were invoked as a reason for opposing such ventures. Right-wingers like Steve Bannon have utilized the Clash of Civilizations thesis to reject immigration to the United States. Perhaps most surprisingly, thinkers around Russian leader Vladimir Putin have argued that their country is the leading defender of a Christian civilization that the rest of Europe has largely abandoned, providing yet another lifeline to a 30-year-old essay.

Huntington would almost certainly abhor many of the uses of his arguments, given his interpersonal decency, frequent travel to universities and legislatures around the world, mentorship of and friendship with people of color, and lifelong support for U.S. interests. “I think he would have absolute contempt for this type of stuff,” said Gideon Rose, another of Huntington’s students and the Foreign Affairs managing editor following Zakaria. “He would have been appalled at the disorder, he would have been appalled at the prejudice, he would have been appalled at the anti-intellectualism. He was no fan of elites, but he was also in no way a populist.”

And yet, by simplifying the world into categories defined largely by culture and religion and declaring them inevitably hostile to one another, Huntington established an intellectual template for what has followed in his wake. By portraying the West as a unique civilization under siege from mass immigration and Islam, he drastically underestimated America’s assimilative power and most Muslims’ rejection of fundamentalist Islam. Even worse, Huntington’s ideas were so powerful and popular that they deepened currents hostile to peaceful coexistence between Western countries and others. One of the most prescient comments on Huntington’s ideas came from the Indonesian Australian writer Wang Gungwu, who observed in 1996, “This is what is so stunning about The Clash of Civilizations: it is not just about the future, but may actually help to shape it.” Wang was right about that, and we are largely worse off for it.

Huntington was a shy political scientist who began teaching at Harvard in 1949. A quintessential WASP, he’d registered as a Democrat the year earlier at the age of 21, met his wife while writing speeches for Adlai Stevenson, advised presidential nominees Hubert Humphrey in 1968 and Michael Dukakis in 1988, and served on Jimmy Carter’s National Security Council. A visit to his archive at Harvard reveals that he offered some thoughts on foreign policy to Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign in 1992, around the time he was putting the finishing touches on the “Clash” essay.

Despite his long relationship with the Democratic Party, Huntington was anything but a partisan hack. Before he gained international fame, he already stood at the top of his profession for his contributions to subfields of political science. His first book, The Soldier and the State, had an enormous impact on the theory of civilian-military relations. His next major work, Political Order in Changing Societies, was a landmark in comparative politics. And his book immediately preceding Clash, The Third Wave, introduced that phrase to encompass the series of transitions to democracy that numerous countries undertook in the late 1970s and 1980s. (It also displayed Huntington’s knack for fashioning memorable neologisms to describe political phenomena.) Mixed in with these achievements were other books and many journal articles he wrote, alongside co-founding Foreign Policy and serving as president of the American Political Science Association. In a 1999 cover story for this magazine on the decline of political science, Jonathan Cohn called Huntington “arguably his generation’s most influential student of international relations.”

With his skeptical worldview, Huntington was slow to see that the Cold War was ending as the 1980s wound down. But when it did, he anticipated not Fukuyama’s pacific ideal but a “jungle-like world of multiple dangerous, hidden traps, [and] unpleasant surprises,” he said in a 1990 lecture. He added, “We need a good word to describe the international relations of this new world … the right phrase to replace [Walter] Lippmann’s Cold War as a label for this much more complicated situation of ambiguous relationships and multiple conflicts.” Over the next two years, he set himself to that task.

Some of The Third Wave had examined the relationships between cultures and democratization. The book argued that changes within the Roman Catholic Church and economic development had led countries with Catholic majorities toward democracy, whereas before the 1970s, democratic countries had mostly contained Protestant majorities. Huntington attached a great deal of importance to culture’s role in political affairs, and “The Clash” was an extension of this. But his thinking evolved in spurts, and it was comfortable with nuances to the point of being contradictory.

In October 1992, Huntington wrote a memo to Bill Clinton’s campaign suggesting the Arkansas governor prioritize the expansion of democracy. “A world in which Russia and China were democracies like all the other great powers would truly be a democratic and a highly secure world,” he wrote. But that same month, Huntington debuted a far more pessimistic thesis about a clash of civilizations in a lecture at the American Enterprise Institute, the conservative think tank.

He adopted the term after reading the historian Bernard Lewis’s 1990 essay in The Atlantic on “The Roots of Muslim Rage.” Lewis argued that the separation of church and state arose from Christian principles, not universal ones. Conversely, many Muslims were reverting to what he called the “classical Islamic view” that deemed secularism, modernity, and the equality of nonbelievers with godly people as heretical. “This is no less than a clash of civilizations—the perhaps irrational but surely historic reaction of an ancient rival against our Judeo-Christian heritage, our secular present, and the worldwide expansion of both,” Lewis wrote.

Lewis was a conservative-leaning scholar, charged as a quintessential contemporary Orientalist scholar by the left-leaning literary critic and Palestinian activist Edward Said. But Huntington was an admirer of Lewis, being a conservative Democrat, as devoted to order, security, and American traditions as any Republican. And so his appearance at AEI was unsurprising. “The great divisions among humankind and the dominating source of conflict will be cultural,” he announced. “The major conflicts will [be] between peoples of different civilizations.” He said he was not offering a prediction but a hypothesis, although that uncertainty decreased in the following years.

Huntington circulated a version of the speech as a working paper for Harvard’s now defunct John M. Olin Institute for Strategic Studies, which he directed (the Olin Foundation was a longtime funder of conservative causes). His students included Zakaria and Rose. Senator Bill Bradley and historian Paul Kennedy also discussed the essay, and Huntington’s archives contain a handwritten note from former President Richard Nixon congratulating the professor for writing the best post–Cold War essay and having “raised issues [in the AEI lecture] that no one else, in or out of government, has adequately addressed.” Even before it was published, then, the essay was generating buzz.

When Zakaria became managing editor, he asked Huntington to adapt the paper as the cover story for the summer 1993 issue of a redesigned Foreign Affairs. “I definitely knew it was going to be big because it was so provocative,” Zakaria recalled. “And he wasn’t famous, but he was famous enough that he had authority.” Zakaria admired Huntington’s prescient understanding of the power of culture in the post–Cold War era and his willingness to dispel liberal illusions around the triumph of globalization, free markets, and democracy.

But nobody, not Zakaria nor Huntington, could possibly anticipate how big Huntington’s essay would be. With some changes made to the Olin paper at Zakaria’s suggestion, “The Clash of Civilizations?” attracted more attention than anything Foreign Affairs had published since Kennan’s Cold War essays, and more than anything it has published since. Editors were deluged with requests to reprint the article and responses from other intellectuals, some of which they printed. Huntington was flooded with interview and lecture requests from around the world, where readers seemed as fascinated by, supportive of, or angry about the “Clash” thesis as were Americans. As much as any article in a popular foreign policy journal can, “The Clash” penetrated into the public consciousness and began influencing world events immediately. The U.S. ambassador to Indonesia cabled the State Department in August 1993 complaining that the article had “caught on like wildfire in Asia,” to the point that “dealing with the issue is as great a challenge for policy and public diplomacy as any in the post–Cold War era.”

What made “The Clash” radioactive was not just its unfashionable pessimism or its author’s establishment pedigree. Rather, it seemed to explain complex global realities in a novel, simple way. The Gulf war could, if one squinted hard enough, impersonate a conflict between different countries from different civilizations. The same was true of the Yugoslav Wars then raging, the Israeli-Arab conflict, and China’s opposition to U.S. policies. Any friction between states with different cultures could appear as evidence of a clash between civilizations, as could any friendship between countries with similar cultures, which Huntington called “kin countries.” Even an inchoate sense that other people around the world were just somehow different from Westerners could be justified in civilizational terms.

Huntington also had something going for him that most political scientists do not: He could really write. His sentences were clear, bold, and blunt, perhaps at times to a fault. “Differences among civilizations are not only real; they are basic,” he wrote. Huntington was notable for his confidence in writing declarative sentences that simplistically categorized billions of people. The world would be shaped, he said, by “Western, Confucian, Japanese, Islamic, Hindu, Slavic-Orthodox, Latin American, and possibly African civilization.” Billions of humans were assigned to these eight groups. Each group possessed their own “philosophical assumptions, underlying values, social relations, customs, and overall outlooks on life.” This cultural determinism was nearly inescapable and explained the world’s complicated political and economic circumstances. “Islamic culture explains in large part the failure of democracy to emerge in much of the Muslim world,” he wrote, minimizing such weighty factors as geography, history, imperialism, economics, and leadership quality. Comprehending Huntington’s paradigm didn’t require knowing any history or global politics; anyone could just look at a globe, see the divisions, and chalk them up to inevitable cultural differences.

Huntington’s blithe generalizations about millions of people recalled discredited modes of thinking. In the book, he wrote that “civilization and race are not identical” but conceded that “a significant correspondence exists between the division of people by cultural characteristics into civilizations and their division by physical characteristics into races.” Civilizations as entities defined by stubborn cultural elements differed from civilizations defined by immutable racial characteristics—but the two were close enough to be kin themselves.

Relatedly, Huntington portrayed the West as unique and fretted that its very survival was threatened by mass immigration and Islam. Mexican immigrants particularly were not assimilating into the United States, inciting a “demographic invasion.” He saw civilizational conflict in such minor developments as Mexican immigrants demonstrating in Los Angeles against a referendum meant to deny state benefits to undocumented people. These sections of his book have largely been forgotten, but swaths of The Clash of Civilizations read like a Trump campaign brochure with footnotes.

Huntington responded to little of the barrage of criticisms the book inspired. He argued that his paradigm was more accurate than any other, and that simplifications of international relations were always necessary. Otherwise, he addressed only what he saw as misrepresentations of his argument, and even then he did so only occasionally. “His modus operandi would be to do his work on a subject, answer a question to his own satisfaction, and then to move on to another topic that he found interesting,” recalled Gideon Rose. However, Huntington, unafraid of being unpopular, did grant many interviews and traveled internationally to address his argument to local audiences.

But while Huntington was largely content to let the furor over his argument rage, he grew increasingly vocal with his alarm about Latino immigration to the United States. When he cast his vote for Bob Dole in 1996, he was voting for a Republican presidential candidate for the first time. “Recent Mexican and Muslim immigrants identify more with their country of origin than with the United States,” he said in 1998. He said multiculturalism had replaced a national feeling among elites, alienating them from ordinary Americans. “If multiculturalism continues to spread, it is likely at some point to generate an ethnic and possibly racist populist reaction from white Americans,” he predicted. “If this occurs, the United States would become isolationist and hostile toward much of the outside world.”

Huntington was correctly, brilliantly anticipating the direction in which the United States was headed, but he absolved white Americans of their xenophobic, authoritarian turn, perhaps because he shared some of their anxieties and prejudices about Latin Americans. His concern about Mexican immigration became a panic, one he said could jeopardize the country’s future, not just its allegedly fragile national identity. His last book, 2004’s Who Are We?, was borderline hysterical about the failures of the United States to remain unified in the face of the “illegal demographic invasion” and cosmopolitan elites. In this final work, Huntington did not just foresee the Trump movement that would emerge more than a decade later; he supported some of its primary grievances. “Cultural America is under siege,” he wrote. “Mexican immigration is leading toward the demographic reconquista of areas Americans took from Mexico by force in the 1830s and 1840s,” he wrote. Huntington suggested that Mexican culture and values were different from American ones, citing observers who believed “Hispanic traits” included mistrust of people outside the family, laziness, low regard for education, and an acceptance of poverty as a precondition to entering heaven. If the United States did nothing to reaffirm its “historic Anglo-Protestant culture,” it would devolve into two countries, he believed: one that retained its traditional values, the other a Hispanicized bloc that undermined what had established American greatness.

After Who Are We?, Huntington commenced a new work about the relationship between religion and nationalism called Chosen Peoples. Sadly, he never finished it, suffering health failures for years before dying in 2008. Even his many critics admitted that few other academics had shifted the world outside the academy as he had.

After 9/11, when The Clash of Civilizations hit the bestseller list for the second time, Simon & Schuster rushed 20,000 new copies of it into print. With extremists claiming to attack major American capitalist and governmental symbols in the name of Islam, it was easy to mistake Huntington for a prophet. Within hours of the attacks, fretful voices worried about making a civilizational clash a self-fulfilling reality. On September 11 itself, Pakistan’s ambassador to Russia said, “This must not be seen as a clash of civilizations between the Islamic and the Christian world. You must pay attention to the fact that every Islamic nation worth its name has condemned this.”

To some degree, his caution was heeded. French, German, Canadian, and Arab leaders swiftly cautioned against perceiving the attacks as part of a clash of civilizations, demonstrating how deeply and widely Huntington’s phrase had penetrated. President George W. Bush repeated that Islam was a great world religion not represented by terrorists and invoked Huntington’s phrase to repudiate it. “This struggle has been called the clash of civilizations,” Bush said. “In truth, it is a struggle for civilization.” Even Henry Kissinger warned against feeding into the narrative of a clash, as did analysts at the Heritage Foundation. Rudy Giuliani, at his zenith disguising himself as a big-hearted statesman, told the United Nations, “Surrounded by our friends of every faith, we know this is not a clash of civilizations. It’s a conflict between murderers and humanity.”

Others were less circumspect, in the United States and elsewhere. “It’s a clash of civilizations,” former Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick said on The O’Reilly Factor on September 13. The Economist praised Huntington’s views on Islam as “cruel and sweeping, but nevertheless acute.” The Atlantic featured a glowing, nearly 9,500-word profile of Huntington, written by the journalist Robert Kaplan. A few years earlier, Kaplan had written Huntington a letter, found in his archives, praising the political scientist for being a bomb-thrower. “The real purpose of the intellectual is to constructively disturb,” Kaplan wrote. “That is exactly what you have done.”

Indeed, Huntington seemed to enjoy the role of provocateur, and it gradually overtook his vocation as a detached political scientist. The Boston Globe profiled his revived fame in a front-page article, and Huntington believed a real clash was forthcoming as the West responded to the attacks, telling the paper, “I fear that while Sept. 11 united the West, the response to Sept. 11 will unite the Muslim world.” He believed that, as Osama bin Laden reportedly hoped, Muslims everywhere would revolt against the West and foment a world war. Soon after, Huntington wrote a Newsweek essay that was more narrow-minded than anything he had written. “Contemporary global politics is the age of Muslim wars,” he argued. “Muslim wars have replaced the Cold War as the principal form of international conflict.” Few other academics were writing anything like this for popular periodicals at the time. Huntington also strengthened the panic around terrorists using deadlier weapons than airplanes to attack the United States, estimating that bin Laden ran a network “with cells in perhaps 40 countries,” and 9/11 had “highlight[ed] the likelihood of chemical and biological attacks.”

Huntington’s caricatured generalizations about Islam legitimized other voices espousing religious and cultural essentialism. Talk about Islam as a dangerous, monolithic entity represented by its most violent elements became mainstreamed. The military historian John Keegan complimented Huntington’s prescience and declared, “A harsh, instantaneous attack may be most likely to impress the Islamic mind.” The syndicated columnist Richard Cohen wrote that “a rereading of [Huntington’s] article shows that much of it has held up” because “whatever happens to bin Laden or, for that matter, the Taliban, the cultural roots of this conflict will persist.” Another columnist, Rod Dreher, wrote in National Review, “it is unarguable that very many Muslims and their leaders despise non-Muslims, attack us rhetorically in religious terms, and wish to see us die for our infidelity to Allah.” He added menacingly, “if there is an Islamic fifth column in this country, the American public needs to know about it.” Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi got in on the action, declaring that “our civilization is superior to Islam.” But his views were widely criticized, and he took the rare step of half-heartedly apologizing.

In the ensuing years of Bush’s tenure, however, fewer apologies would be made for such denigrations of Islam as a religion and a civilization. As jihadists occasionally attacked Western countries, Muslim immigration continued, and Western armies occupied Iraq and Afghanistan, Islamophobia became more politically acceptable, first on the religious right, then among think tankers such as Steven Emerson and Daniel Pipes, and, finally, among more moderate intellectuals such as Martin Amis and Sam Harris. Amis said, “I don’t think that we can accommodate cultures and ideologies that make life very difficult for half the human race: women.” By the time Barack Obama ran for president, anti-Islamic sentiment was widespread enough to facilitate frantic rumors about his religion. A language was needed to sanitize the anxieties of what was often sheer bigotry, and Huntington provided the lexicon and establishment imprimatur.

But even as Huntington’s thesis hardened into conventional wisdom in segments of the foreign policy and journalism worlds, matters took quite a different direction in the academy. In the book version of Clash, Huntington laid down a simple marker to help determine the value of his argument. “A crucial test of a paradigm’s validity and usefulness is the extent to which the predictions derived from it turn out to be more accurate than those from alternative paradigms,” he wrote. Soon after he published those words, scholars took up the challenge and began testing his theory. Among the first was a 2000 paper in Journal of Peace Research, in which three political scientists examined conflicts between 1950 and 1992 to determine if states from different civilizations were likelier to be in conflict, and to assess whether other theories better accounted for these conflicts. “There is little evidence that civilizations clash,” they found. Traditional international relations theories like realism better accounted for world events. Huntington responded that his thesis was meant to apply to the post–Cold War world, not the bulk of the years his critics had studied, although his essay made numerous present-tense statements about anti-Western civilization alignments, such as, “A Confucian-Islamic military connection has thus come into being, designed to promote acquisition by its members of the weapons and weapons technologies needed to counter the military power of the West.”

The following year, two different political scientists looked in International Studies Quarterly at the relationship between civilizations and wars over nearly two centuries, between 1816 and 1992. They, too, found little support for Huntington’s theory. “Most importantly, our analysis reveals that during the post–Cold War era (1989–1992), the period in which Huntington contends that the clash of civilizations should be most apparent, civilization membership was not significantly associated with the probability of interstate war,” they wrote.

In 2002, still another scholar looked at conflicts between 1946 and 1997, also in Journal of Peace Research. This analysis, too, found that “state interactions across civilizational lines are not more conflict prone.” The same was true for the eight years since the Cold War ended, pace Huntington. Again in 2002, when Huntington’s retrograde ideas about Islam were coursing through American life, a paper in the British Journal of Political Science looked at data to assess whether ethnic conflicts since the Cold War that could be defined as civilizational had increased in quantity or intensity, let alone defined the period. Alas, “civilizational conflicts make up only a minority of ethnic conflict in the post–Cold War era.” Nor were those conflicts more intense than those wars waged by states in common civilizations.

The research empirically finding Huntington’s theory to be wrongheaded continued to mount. A 2006 European Journal of International Relations paper found that “violence is more likely among states with similar ties, even when controlling for other determinants of conflict.” Other scholars took aim at particular aspects of Huntington’s thesis. In a 2009 article in the British Journal of Political Science, two political scientists looked at data to assess civilizational clashes not in terms of war but in terms of terrorism. The Clash had gained renewed attention following 9/11 after all, and Huntington had cited jihadist terrorism against the West as evidence of his thesis. “Significantly more terrorism is targeted against nationals of the same country than against those of other countries,” they found. Examining Huntington’s most controversial claim, they concluded that there was “no significant effect with respect to terrorism from the Islamic civilization against nationals of all other civilizations in general.” As for migrants, a 2003 report in Comparative Political Studies crunched the numbers and determined that “diasporas and immigrants did not increase intercivilizational conflicts.” Later studies have confirmed these shortcomings and added more.

Not all academic research pointed away from Huntington. A 2010 article in the journal Cooperation and Conflict buttressed several components of Huntington’s theory, looking at wars between states from 1989 to 2004. “The findings illustrate that Western countries paired with a country from any other civilization, in particular the Islamic bloc, increases the likelihood of violent international conflict,” it read.

But the analysis was an outlier: Most studies empirically testing Huntington’s argument found the data lacking. Peer-reviewed studies aside, the world’s conflicts demonstrate the failures of Huntington’s thesis. Huntington’s wrongheaded belief that the Muslim world would unite in response to what was then called the war on terrorism revealed his limited understanding of the divisions among, and motivations of, the hundreds of millions of people in Muslim-majority countries, who are as divided along nationalist, ethnic, and intra-religious lines as any other civilization. Similarly, by far the deadliest war of the twenty-first century so far has been the Second Congo War, which lasted from 1998 to 2003. Most of the three million people killed in the war were civilians. The ongoing Syrian Civil War has claimed the lives of more than 300,000 civilians. That number is similar to the number of people killed in Sudan in the war that began in 2003. These three wars top the list of the worst conflicts of the twenty-first century, and they have something in common: they were largely fought within civilizations.

And then there is the Russo-Ukrainian War, the conflict with the most potential to escalate into a nuclear exchange. In The Clash, Huntington argued specifically that the future relationship between Russia and Ukraine would serve as a test of his theory. He rebutted John Mearsheimer’s claim that the two countries were headed for conflict because of a long, undefended border, a history of mutual enmity, and Russian nationalism. “A civilizational approach, on the other hand, emphasizes the close cultural, personal, and historical links between Russia and Ukraine and the intermingling of Russians and Ukrainians in both countries, and focuses instead on the civilizational fault line that divided Orthodox eastern Ukraine from Uniate western Ukraine, a central historical fact of long standing,” Huntington wrote. “While a statist approach highlights the possibility of a Russian-Ukrainian War, a civilizational approach minimizes that and instead highlights the possibility of Ukraine splitting in half, a separation which cultural factors would lead one to predict might be more violent than that of Czechoslovakia but far less bloody than that of Yugoslavia.” Here as elsewhere, the civilizational approach proved demonstrably, even catastrophically wrong, highlighting the limits of a perspective that overemphasizes the role of culture in world affairs. Putin might eventually conquer some of eastern Ukraine, but that occurrence wouldn’t result from some civilizational kinship. “By May 2022, only 4 percent in Ukraine’s east and 1 percent in the south still had a positive view of Russia,” according to an analysis by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Amazingly, people who had called themselves Russians living in Ukraine are now patriotic Ukrainians. “Cultural and historical preferences have also changed dramatically. Sixty-eight percent of respondents from the south and 53 percent from the east now describe Ukrainian as their native language,” the Carnegie analysis found, consistent with other studies. These evolutions illustrate how cultural identities are far more malleable than Huntington suggested.

But even as research and events have discredited Huntington’s argument, it has found important adopters among the far right worldwide. Steve Bannon, the influential adviser to the Trump administration, has adopted variations of the ideas, saying, “If you look back at the long history of the Judeo-Christian West struggle against Islam, I believe that our forefathers … kept it out of the world, whether it was at Vienna, or Tours, or other places.” No wonder that Trump’s White House extensively limited immigration, singled out Muslim refugees as primed for violence, overstated the threat posed by jihadist terrorists, and made defending an apparently embattled American civilization fundamental to its worldview.

Beyond the United States, right-wing figures globally increasingly used the language of clashing civilizations. Pim Fortuyn, a pioneer in the far-right populist crusade against Islam, represented himself as “the Samuel Huntington of Dutch politics.” Russian leader Putin styles himself as the defender of Christendom, saying “Euro-Atlantic countries” were “rejecting their roots,” which included the “Christian values” that were the “basis of Western civilization.” Viktor Orbán, the Hungarian prime minister who has become the de facto leader of Christian conservatives, told an American conference of right-wingers that “Western civilization” was under attack by people who hated Christians and globalists who “want to give up on Western values and create a new world, a post-Western world.”

Huntington likely would have despised some of his new fans. He was a nationalist who was skeptical of immigration, but he was simultaneously a small-d democrat who devoted his life to defending America’s interests and its democratic system. Most importantly, he wanted to avoid the clash of civilizations he foresaw, not provoke one, as people like Bannon are eager to do. Praise for a violent, anti-Western dictator like Putin is unimaginable coming from him. But however inadvertently, Huntington furthered the cause of far-right populists everywhere by giving them a language and academic cover for their apocalyptic, xenophobic sentiments. These reactionaries have targeted Muslims and migrants with brutal rhetoric and actions, fueling the global, cultural, and religious tensions that Huntington wanted to reduce. But that is the thing about theories: Sometimes they clash with the real world, to disastrous effect.