Consumer boycotts were once thought of as a tactic primarily employed by the left, but the right has recently used them to great effect—just ask Anheuser-Busch and Target, to name just two companies that have recently been caught in conservatives’ crosshairs. Perhaps not surprisingly, given our polarized moment, there’s a movement among conservatives to create an economy of explicitly right-wing alternatives to everyday products. What caused the rupture between conservatives and big business? Is the notion of a parallel economy even realistic, or is it primarily about bringing corporations to heel on social issues? On episode 70 of The Politics of Everything, co-host Laura Marsh surveys the right’s parallel economy with Kathryn Joyce, who wrote about it in the October issue of The New Republic.

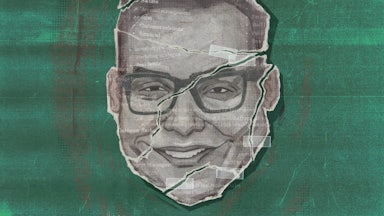

[Clip]: This month I celebrated my day 365 of womanhood and Bud Light sent me possibly the best gift ever: a can with my face on it.

Laura Marsh: That’s Dylan Mulvaney in a video she posted back in April. The clip is a typical unboxing video. It’s the kind of thing you see on Instagram and YouTube all the time, where an influencer shows off a cool product a company sent them. But this one video prompted a furious backlash from the right. Mulvaney is trans, and she was inundated with threats and abuse.

At the same time, prominent figures on the right encouraged a boycott of Bud Light and its parent company. This is Kid Rock firing an AR-15 into a stack of beer cans.

[Clip]: Fuck Bud Light, and fuck Anheuser-Busch. Have a terrific day.

Laura: One entrepreneur even marketed woke free ultra-right lager for $20 a six pack as a replacement. This boycott of Bud Light in the promotion of conservative-approved beers in its place is part of a bigger movement.

The right is increasingly targeting companies it sees as woke with similar campaigns and trying to push “anti-woke” products and services in their place.

[clip] Charlie Kirk: I’m going through my kitchen, and I’m going through my refrigerator and I’m asking, was this ketchup bottle woke?

Laura: Today, we are talking with reporter Kathryn Joyce, who recently sorted through these efforts in a feature for The New Republic. We’re talking about how these boycotts began, what the people behind them want, and what it says about the future of the right in the United States today.

I’m Laura Marsh. This is The Politics of Everything. And before we start the show, I have one housekeeping note: Alex Pareene is out this week, but he’ll be back next episode.

Laura: When the right boycotts a product, they pick a new one to support instead. In fact, the right is building a whole parallel economy made up entirely of right-wing-approved companies and products branded as anti-woke.

Kathryn Joyce surveyed this growing movement in her feature in the new issue of The New Republic. Kathryn, welcome to the show.

Kathryn Joyce: Thank you so much for having me.

Laura: So take us back to this spring for a moment. Bud Light was certainly the highest-profile boycott, but there were other companies that got caught in the conservative crosshairs as well. Can you tell us about a few of those?

Kathryn: Yeah, absolutely. Bud Light was sort of the start. But in May, a lot of attention turned on Target.

Laura: And what prompted the Target boycott?

Kathryn: That was largely over Pride Month. Target had released Pride Month–themed merchandise, including T-shirts and things for children—also swimsuits. A lot of disinformation went out around this time, claiming that Target was selling things that it wasn’t, like “tuck-friendly” swimsuits for children. There were also claims that Target was selling Satanic-themed merchandise. And so you started seeing right-wing, vigilante activists going into Target and filming themselves, having these kind of freak-outs on the staff or on other customers there, confronting people.

And Target also took a fairly big financial hit, and also Walmart and Kohl’s, because they had pride merchandise. The Lego company, not even for a real reason but because there was this false rumor that got spread that they were selling transgender building sets, something that was not actually happening.

Laura: All the examples you’ve given make the term “boycott” seem so insufficient because these are not just instances of people saying, “Oh, I don’t like the politics of this company. I’m not gonna buy their stuff.” These are campaigns of harassment. They’re extremely confrontational and heated. It’s not just saying, let’s use our purchasing power to put pressure on companies that we don’t like.

Kathryn: Yeah, it ballooned out. It even kind of ended up taking in conservative companies as well. Ten years ago, if you would’ve thought that conservatives were boycotting Chick-fil-A, which at the time was being held up as this just paragon of conservative corporate virtue—this year, among this kind of boycott frenzy, somebody found out that Chick-fil-A has had for years an existing diversity program, and people were saying, “Not you too, Chick-fil-A!” and somebody posted a video from Turning Point USA talking about how Chick-fil-A is no longer the Lord’s chicken.

Laura: If it ever was.

Kathryn: If it was.

Laura: The boycotts attracted a lot of attention, but in your piece you suggest that the movement to create a kind of parallel economy began a bit earlier than this, in the beginning of the Biden administration. Can you just talk us through the origins of some of this activism?

Kathryn: The first place that I started noticing it was in January 2021. I was paying a lot of attention to the Catholic right then, and one day, one of the Catholic-right news sites hosted Andrew Torba for an interview.

And Torba is the founder and CEO of the far-right social media platform Gab, which, these days, is best known for basically being a pit of really rampant antisemitism and a lot of white nationalism.

Laura: It was kind of founded as a place for people who are blocked from Twitter to go to, right?

Kathryn: One of many. With Parler and Rumble for video, all of these are already early examples of the parallel economy, but Gab stands out as being particularly vicious. When there was the terrible 2018 mass shooting at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Synagogue, that ended up entangling Gab in a lot of controversy because the mass shooter was a frequent Gab participant. He had posted a lot of his thoughts and kind of threats on Gab. And also in the aftermath of that shooting, Gab was dropped from its web-hosting service and also from payment processors like PayPal and Stripe.

And in response to that, Andrew Torba, the CEO, had this really self-involved response. He later wrote, from that moment forward, we decided we would never again allow something like this to happen, not to Gab and not to anyone else who shares his values. And of course, the thing that should never happen again is not the mass shooting that he’s talking about, but them being demonetized in response to having been a platform for this most vicious, far-right activity.

Laura: So people like him are already thinking about the structure of the internet and how they can avoid relying on services that will cut them off for their actions. That’s the back end of things. What about the day-to-day? How extensive is the parallel economy more broadly? Is it possible to get through an entire day just using products and services from the parallel economy at this point?

Kathryn: If your day consists largely of drinking parallel-economy coffee and eating parallel-economy beef jerky or duck jerky or buffalo jerky, there’s a lot of kinds of pemmican and dried meats and things like that.

Laura: Well, what’s coming out in the list of stuff you’ve just mentioned there are all products that already feel explicitly branded as male—like really strong coffee and jerky that you can take out into the wilderness with you, even though you probably drove there in an incredibly expensive SUV and you’re only going to be there for an hour or something. A lot of this is about making sure that products are really touted as manly.

Kathryn: Manly and patriotic and freedom loving, for sure. One of the more successful parallel-economy coffees, called Black Rifle Coffee, it’s got these different roasts named after different kind of weapon terms. I think that the smooth roast, the light blend, is something about a silencer.

Laura: Oh my goodness.

Kathryn: A lot of it is like that. But they are definitely trying to go a lot bigger. I think if it was just that—and it has been that for a long time—that’s kind of easy to mock. But there are also things like parallel financial advisory services or health plans. There is some survivalist stuff in there too, but also, there are cell phone carriers. Um, there is also a large marketplace that is sort of bidding itself to be where all of these products can be found under one banner.

There’s going to be a conference next year tied into different digital currencies, some of which are already pretty associated with the far right. So it is definitely something that they are trying to blow up into a much bigger ecosystem.

There are all of these different product substitutions that they list. So you can swap out Patagonia because, in their words, they have literally handed their company over to Mother Earth and because they support Black Lives Matter, and you can choose this patriotic “outleisure” clothing company instead, and they’ve got that for everything: for protein bars that are anti-abortion, for anti-vaccination probiotics, for teeth whiteners, all kinds of things, eyewear—it, it goes on and on.

Laura: Incredible. But a lot of those offerings seem to come from companies that are operating, at least at the moment, on a fairly small scale. And I wondered, how much uptake you think this parallel economy is really getting? There might be people who are pretty fired up by the Bud Light stuff, and maybe they bought that $20 six-pack once, but Bud Light’s kind of cheaper, and that’s what people are used to drinking.

Kathryn: Yeah, and I think you have to get the six-pack shipped to you. You have to plan your parallel drinking pretty far in advance, and then you have to pay an awful lot of money for it.

Laura: It’s an interesting strategy because typically, you think that a business can influence culture by becoming very successful and then imposing those values through its base of consumers rather than saying, “Well, these are already your values. We don’t really have a business plan, but buy this stuff and then hopefully we’ll get successful.” Do you think these really are serious businesses or are they essentially merch for a kind of political ideological campaign?

Kathryn: I think a lot of it feels very much like political merch. If you go into certain stores in certain parts of the country, you might see some of these products.

Laura: I’ve seen Black Rifle Coffee in the wild.

Kathryn: Yeah. Or you might see a T-shirt for one of these products in the wild. I feel like they seem to have a much bigger life, such as it is, on social media. So a lot of this just does feel confined to unreality or not the concrete world so much. It is going be a lot easier to end up going to Target or a place like that if you need to buy something that you need for now, rather than going and finding the alternative and waiting for it to ship to you.

Laura: After the break, we’ll talk about the Wall Street debut of an anti-woke marketplace, as well as the right’s changing stance toward big business.

Laura: We’ve

been talking to writer Kathryn Joyce about the rise of the parallel economy. In

July, an anti-woke marketplace called PublicSq. made its debut on the New York

Stock Exchange as a kind of right-wing Amazon.

Laura: Kathryn, I tried to log on to PublicSq., and you have to sign up for an account, which I didn’t feel like doing because I don’t want to participate in the parallel economy. So what is PublicSq.? How does it actually work? What are they trying to do?

Kathryn: Yeah, so PublicSq. builds itself as an Amazon alternative and the centerpiece of the parallel economy. They want to be the place where all of these different parallel economy products have their business home. They claim to have a little over a million users now, and as of this summer, I believe just under 56,000 different vendors are signed up. They’re selling all kinds of things there—everything from clothing and eyewear to vitamins and supplements.

And then this July, they ended up launching as a publicly traded company at the New York Stock Exchange. So it was this really interesting scene. Donald Trump Jr. is involved with PublicSq. So is Kimberly Guilfoyle, the former Fox News host and Donald Trump Jr.’s fiancée. Also the former chief of staff for Mike Pence. And so they are all there on the balcony of the stock exchange alongside the two men who are launching this company publicly. And when it launches, there’s this moment that ends up getting replayed across conservative Twitter and other social media, where the crowd of supporters that PublicSq. has brought with them applaud, and then they burst into this really loud, really long chant of “U-S-A, U-S-A!” and Jim Cramer, the television financial analyst, looks very annoyed at all that’s going on. And this moment that just gets repeated across conservative media is: Here we are; the deplorables are taking over Wall Street and the patriot economy has arrived.

Laura: Right. There’s something about that scene that’s so jarring, and you point this out in the beginning of your piece, which is that the idea that the right has to conquer Wall Street seems utterly bizarre. Big businesses dominated by conservatives. The Republican Party is traditionally extremely friendly toward big business and toward Wall Street. So how do we get to this point where Donald Trump Jr. is able to stand there and make gestures to the effect that “we are taking Wall Street back”?

Kathryn: Yeah, it’s kind of bewildering, but it follows from this narrative that’s been building on the right that conservatives have lost so much control over the culture and over various sorts of non-governmental institutions in society, that they are going to have to go on this campaign to retake those institutions. For a long time, Republicans and big business traditionally went hand in hand and they feel, in a lot of ways, betrayed that companies are breaking with them on different social issues.

Laura: What do you think the turning point was for them? When did this feeling that those two groups are not aligned begin?

Kathryn: I think a kind of prominent one was what happened between Governor Ron DeSantis in Florida and Walt Disney back in 2022. DeSantis and his administration and his allies had been pushing all of these pretty radical measures through their state legislature, including the Parental Rights in Education Act, which is called widely by its critics the “Don’t Say Gay” law. This severely limited how teachers or anybody in schools could talk about or, in some cases even acknowledge, the existence of LGBTQ issues or people.

And when this happened, of course, Disney came out and said, “We don’t think that this is the right move.” And they weren’t doing this because Disney is such a wonderful, progressive organization. They were sort of pushed in that direction in part by employees; they were also responding to what they thought that the greater share of the public wanted. But they got kind of pulled into this debate, and DeSantis was furious that his law was being criticized by Disney—which is just this economic powerhouse in the state—and, together with Christopher Rufo, ended up fighting back.

Chris Rufo, of course, was the kind of architect of the anti–critical race theory moral panic. But he also laid out this strategy that the first step in fighting back against this, is you have to get the average, conservative citizen pissed off about things that they probably weren’t pissed off about before. Concepts like diversity, you have to convince them that this is leftist code. And then you have to get them whipped up enough that they are going to demand change, including demanding some government action against big business, which is really interesting because, again, this is the Republican Party, which has been the ultimate defenders of the rights of big business to do whatever they want.

And so this was changing the arrangement, and it led to all of these really furious demands for action against Disney. So at the state level, people in the legislature were threatening Disney with revoking its special tax district. And at the federal level, people were saying when Disney comes to renew its copyright applications, Congress should just say no. So it’s a fundamental change in how big business and Republicans are relating to each other in general.

Laura: Disney is an interesting example because it is a beloved company by the public in many ways, but it’s also an entertainment company. And in that way, I think it’s a prime target for conservatives. You only have to look at the way Ben Shapiro got incredibly whipped up about the recent live-action version of Little Mermaid, and there’s all this furor about Snow White. Are there certain companies that are attracting these boycotts more than other certain types of companies? I’m thinking of Bud Light being a beer, that’s obviously something that, again, is easy to kind of latch onto in a culture-war sense.

Kathryn: Yeah, one of the people who I spoke with for this story pointed out that a lot of conservatives just assumed, Bud Light is ours; Bud Light is emblematically conservative. Not really realizing that’s not all it is.

So I think, yes, sometimes it is these companies that are seen as representing something that is supposedly theirs. I think Target being just a kind of really super-basic megastore probably also fits that bill, as does Walmart. But I think you see it in different sorts of ways as well. They are also going after big banks and financial firms that are involved with promoting more environmentally conscious standards for their lending or companies that have any sort of diversity policies. It’s really any company that is doing anything against this increasingly strident right-wing point of view— which is also most companies. Most companies have diversity policies. Most large companies do have some recognition of Pride Month and, again, not because they are progressive but because this is how they avoid lawsuits from staff in the first instance and how they appeal to a broader base of consumers.

Laura: It feels worth pointing out that the initiatives that these companies are doing— and having a DEI policy or endorsing Pride Month—are not things that the left particularly commends them for, right? There is a critique from the left that a lot of these policies are just gestures at inclusion that are pretty empty.

Kathryn: Yeah, absolutely. I think that’s why we have terms like “pinkwashing” or “greenwashing,” or one that I heard while reporting this, “wokewashing.” The same companies that are getting boycotted and criticized by the right for supposedly going woke are being criticized, I think with good reason, by progressives because they are mostly just talking a lot. Large banks or investment managers have attracted a ton of right-wing ire for saying, We’re going to limit our lending to companies that are drilling new oil and gas wells or are building new coal-fired power plants. Those companies are still, in a lot of cases, getting really rich off of oil. So they’re getting this reputation without really earning it, and at the same time, they’re being completely lambasted by the right.

Laura: I want to talk about the use of boycotts in all of this. Typically we associate boycotts with the left and with social justice movements. What do you think is different about the way the right is doing this?

Kathryn: Yeah, I think that association is there—that boycotts and consumer activism, these are tools of the left—but it’s always been a little more complicated than that. Lawrence Glickman, a historian at Cornell, has written about this a lot in looking at how pro-segregationist activists in the South in the 1950s and ’60s were calling for boycotts of car companies that supported integration or even boycotting television shows that had interracial casts.

I think that there had been concern, even among leaders on the right, about how well this would work. Ted Cruz at some point in the spring said, This is all well and good, but traditionally, conservatives have not been very good at following through on their boycotts. But Professor Glickman did tell me, this does feel a little different. This is going on longer and has more durability than some of those earlier boycotts did, and also corporations seem more frightened than they had in the past. There is a sense that maybe this is leading into a new moment, because we have just this deeply embedded polarization at this point and consumer politics is being brought into it, and the ways in which consumerism becomes a marker of identity is now more deeply tied to people’s sense of values.

Laura: Do you think that it’s possible to be a national brand at this point and avoid getting tied up in these culture wars because you can’t keep both sides happy?

Kathryn: Yeah, that is what a lot of the experts I spoke to said—that it increasingly feels hard for businesses to find a middle path where they are not pissing off the right because they have supported diversity or LGBTQ equality and they’re also not pissing off the left for completely ignoring those things.

Laura: What do you think the ultimate goal of this movement is? Because they talk about wanting to create a parallel economy, but that seems like an incredibly small-scale ambition. It seems unrealistic that the goal is just to have people drink a different type of beer. Is there a larger program here of trying to discipline companies or take over the economy? Where do you see this heading?

Kathryn: I think that there are multiple motivations that are coexisting at once. There are a lot of small-scale parallel economies that are trying to capitalize literally on this moment, which to me seems like grifting. I think probably from their side, they are trying to meet a market demand for nonwoke health care alternative products, for example. I think that a lot of this is about beating big business back into submission in some ways, which feels like a very funny thing to say. Big business does not really need our protection, or it has not, traditionally, but I think a lot of it is about the idea that “you are a cultural institution that should be affirming and endorsing and supporting, through your actions, our right-wing values. And if you don’t, we are going to punish you.” And they’re coming up with a lot of legally creative ways to go about this—trying to use all of the tools at their disposal to punish companies that stopped being good conservative foot soldiers and attempt to bring them back into line.

Laura: Kathryn Joyce, thanks so much for talking with us.

Kathryn: Thank you so much.

Laura: You can read Kathryn Joyce’s article, “Ketchup With Those Fries? Sure—as Long as It’s Anti-Woke,” in the October issue of The New Republic or at NewRepublic.com.

The Politics of Everything is co-produced by Talkhouse. Emily Cooke is our executive producer. Lorraine Cademartori produced this episode. Myron Kaplan is our audio editor. If you enjoyed The Politics of Everything and you want to support us, one thing you can do is rate and review the show. Every review helps. Thanks for listening.