Celebrity has a deranging effect on many people. Social media and reality TV may have made this worse, or perhaps just more visible. Either way, unhinged behavior related to fame seeking is now so ubiquitous it feels banal. Social media is ridden with obsessive parasocial relationships, both positive and negative, directed even at people with tiny profiles. Reality TV and influencer culture have created a version of fame that is stripped back: a kind of celebrity who does not possess some extraordinary quality or talent but simply wants attention and has been willing to do whatever the algorithm demands to get it.

Technically this is great subject matter for a novel, but one difficulty in writing about any of this is that it could make for a boring book. Most white-collar jobs revolve around entire days spent sitting on the computer, so a book full of influencers all doing likewise, posting their photos or curated lifestyle updates and scanning for likes, doesn’t provide much by way of escapism.

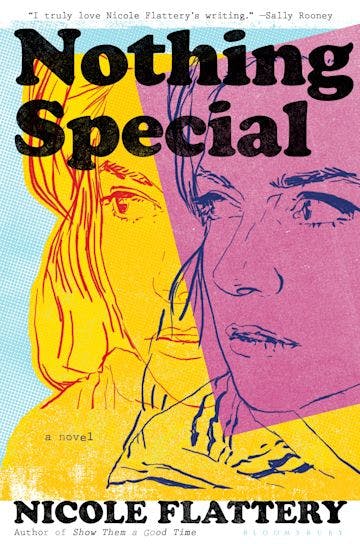

Another difficulty is trying to write a protagonist who would have something interesting to say. An influencer would be tricky; they’re too invested in the system. A crazed fan or stalker would represent the deranged response to fame well (as in the 2017 film Ingrid Goes West), but their self-awareness and ability to comment on this would be limited. Ideally the protagonist would be cynical enough about fame to make fresh, surprising observations but interested enough to be thinking about fame a lot in the first place. This is what Nicole Flattery has fashioned in Mae, the protagonist of her debut novel, Nothing Special.

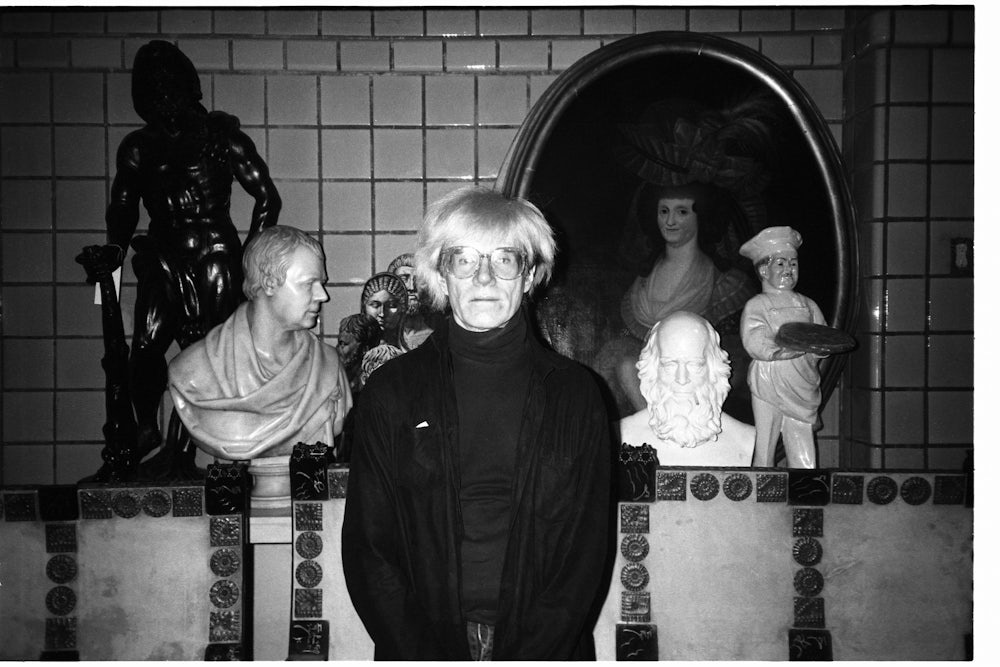

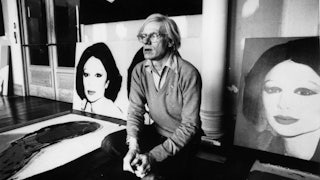

There were two teenage girls who worked on Andy Warhol’s book, A: A Novel. The book (perhaps dubiously framed as a novel) was inspired by Ulysses. Warhol originally conceived of it as a straight transcription of 24 hours in the life of Ondine, one of his original superstars. It ended up consisting of a few separate days’ worth of recordings, including various other Factory characters such as Edie Sedgwick. In Nothing Special, Flattery imagines the lives of the girls who made the transcripts and how they felt about their work. They turned Warhol’s idea into text, which they never got any credit for. What Flattery also articulates is that, through the voyeuristic nature of their project—in which they spend their days listening to and documenting the lives of strangers acting out exaggerated versions of themselves—these girls were exposed to a primitive version of social media and the celebrity culture we’re all now saturated in.

One of the girls is Mae; the other appears as a character named Shelley, who is prim, fastidious and, frankly, out of sync with her hip surroundings. The book opens in the year 2010. Mae is a woman in her sixties who views her, now far from glamorous, life with a dry, offbeat sense of humor. “Sometimes, I become embarrassed in short, unexpected flushes when I see my life clearly as it is now—the chat shows I keep on rotation, my underwear rising coarsely over my trousers as I reach for a box of cereal in the supermarket,” she thinks to herself in the early pages.

Mae’s beautiful, charismatic, and difficult mother has died recently in the retirement home Mae could barely afford to keep her in. The death has prompted Mae to think back over their relationship and her own life, particularly the year she found the Factory and ran away from home, starting a decades-long rift with her mother. In the end, Mae sees her mother’s pain more clearly than any she caused: “My mother was never capable of real cruelty. Everything I’d mistaken for cruelty had been disappointment, heightened emotion with no release, a desire for human contact she wasn’t getting.” But Flattery chooses not to let this perspective soften Mae’s memories of her earlier life. When Mae thinks back to her time in the Factory, when the bulk of Nothing Special is set, she remembers things as she saw them then. She is as naïve, occasionally cruel, and hopeful as a teenager would be.

In 1966, Mae is 17. She is about to run away, but for now she is living in a cramped apartment in suburban New York with her mother, who is working as a waitress in a nearby diner. In Mikey, an affable, down-on-his-luck man her mother brought back from the diner, Mae has a friend more than a father figure. He sleeps on their sofa and occasionally, on drunken nights, in her mother’s room. It would be easy to fashion him as a creep, but Flattery doesn’t deal in stock types. He comes off as the book’s most decent character, and the tenderness of his and Mae’s relationship is one of its most striking elements. As she reflects on the “aura of failure” that follows him—his patchy employment history and his habit of getting himself fired—Mae thinks: “I considered him one of the smartest people I knew.” This perspective is partly what makes Mae fascinating as a character too: She is rebellious in the way that teenagers can be, and over the course of the book we see in her an anti-conformity that she never grows out of.

Mae is not beautiful, or clever, or brilliant in any way, but she has a stronger sense of self than anyone around her seems to, which makes her quietly extraordinary. It also makes her the kind of person who can get as close to the Factory as she does and not be sucked in by what it promises. Because what does fame offer other than the adoration, which is to say, the approval, of other people?

Mae’s desire is not fame or love, but self-reinvention. She has dropped out of school, after being shunned by her friend Maud because she confessed to being excited by the spectacle of another student fainting. Since then she has spent her days riding the escalators in Macys and Bloomingdales, hoping they might be a portal to a different kind of life. “I wanted men to notice me and I wanted something amazing to happen, something unlikely,” she thinks. In a roundabout way her plan works. It is here she meets Daniel, a man in his twenties who takes her back to his mother’s luxurious apartment. They sleep together and he vanishes the next morning, leaving Mae alone in the apartment feeling used and silly. But when she meets his acerbic mother in the kitchen, she is given a business card for a mysterious doctor to contact; and the doctor, in turn, helps her get a job with Warhol.

Of course, Mae is not cynical about the Factory when she first arrives. The glittering new world (literally, Warhol had the inside of the building painted silver) seems to offer freedom. On her first visit, which turns out to be a trial for a job as a typist, she watches a woman cut off strands of her blond hair and drop them onto the floor and thinks:

I knew the same transformation was available to me. I could become someone of my own invention. It was possible that I could kill the person I had been by doing the right work, by producing, by impressing these people. It didn’t occur to me that every girl in that room had the exact same ambition.

She’s a good typist and she is hired and soon gets tasked with a special project, helping Shelley type up boxes of tapes, recordings of Ondine and Warhol’s other stars hanging out and partying. Shelley has traveled to New York from a small town in search of adventure, is “unshakably suburban” and conspicuously out of place among Warhol’s collection of bohemiams. But Mae admires her fastidiousness, her dignity, and her hunger (“she was rabid for any kind of experience,” Mae thinks, at one point). Shelley and Mae forge a friendship, and Mae considers them a pair of misfits, distinct from the fame-seeking characters who surround them.

Meanwhile Mae is sucked into the world of the tapes, more than she ever admits to anyone. In one conversation with Shelley, she shrugs them off as dull while “thinking of the rush of adrenaline and fear I felt as I watched my tape begin its rotation.” She finds she has an almost obsessive drive to work transcribing them, sitting at her desk till well into the evening, barely registering that the sun has set. She considers the world of the tapes exciting, but she also loves bringing the project to life: “It was, I realized, the first time I felt total connection to the work I was doing.” Mae discovers that she gets the sort of thrill out of this work that everyone else in the Factory seems to think they would get out of performing.

There is more to the task than straightforward transcription: Mae is attempting to craft a transcript that can somehow capture the vitality she can hear on the tapes. It’s a fine art, and she and Shelley each strive to be the best at it. Shelley is so skilled that if the subjects “breathed on the tapes, she’d transcribe it.” Mae is “pained” when she thinks “of how good her pages were, how accurate and real and colorful. How she could probably make you feel like you were in the room with them.” Typing turns out to be more like writing. She and Shelley are really engaged in the work of a novelist, of bringing a world to life on the page.

As Mae’s months in the Factory wear on, however, she starts to realize that, since the stars made the concept of performance for its own sake seem appealing, it has become a commodity with a value to a different kind of person. The old stars were ugly, bad, “sick” characters (“they had their obvious addictions, but they also had hepatitis, rotting limbs, open sores”). Now there is a more calculating, shrewder kind of person showing up: “the new people.” They begin to arrive at the Factory in waves. “Their trips to the studio were only about getting somewhere else,” Mae observes. And, in a passage that evokes the near-defiant boringness of today’s reality TV stars and influencers, she thinks: “No, the new people weren’t my kind. They were too controlled. People whose desires were that naked weren’t any fun to figure out.”

The sheen has worn off everything. The parties are repetitive, and Mae and Shelley are always on the outskirts anyway: “No matter what we did at the parties, we couldn’t get any closer to the people on the tapes.” Even Shelley turns out to be a disappointment, when Mae accidentally walks in on her auditioning to be a star and discovers Shelley really did want fame all along, just like the “new people.” Mae thinks: “It was worse than anything I’d seen in my life, because she didn’t belong there. She belonged with me, behind the typewriters.”

The only thing that never really wavers is Mae’s dedication to her work. She and Shelley leave the Factory after an argument, leaving A: A Novel unfinished. This looks like it may be the end of Mae’s involvement with the whole thing. Then a few months later, after Warhol is shot, her supervisor from the Factory finds her and asks if she will complete the job. Mae pretends to deliberate over this, but she knows she will have to accept:

I knew if I had to go back to the start to work on the book, I’d do it. I’d give up everything. I’d suffer all over again. Maybe [the superstars] felt the same way, maybe they always had. All their misery laid bare in the service of art. Out of the garbage and into the book.

There are similarities between Nothing Special and Veronica, by Mary Gaitskill—in which a former model looks back at her time in a glamorous setting that wasn’t all it was cracked up to be. In both books the nuances and complications of female friendship, the bond between mothers and daughters, and the rebelliousness of youth culture are explored. Both are set in a similar era in New York. But the book I found myself thinking of most while reading Nothing Special was Star by Yukio Mishima, a tale about a jaded young actor in 1960s Japan, fed up with the demands of his work schedule and managing his public image. One line from Star, in a passage about how aspirational fame seems from the outside and how hollow it turns out to be, kept coming to mind: “For a star, being seen is everything, but the powers that be are well aware that being seen is no more than a symptom of the gaze.”

When I read Star again to check the wording of that quote, I was surprised to find more parallels too. Both books have a caustic, funny narrator and share certain fixations, particularly a sort of reverence for ugliness. This is from Star on ugliness: “Kayo would never tell you being ugly made her safe.” And this is from Nothing Special: “The staff were all chillingly attractive too. Maybe there wasn’t a single ugly, clumsy person left in New York.”

There can be a tendency to attribute the way people behave on social media almost entirely to the fact it exists, to the malign influence of the algorithm and “our tech overlords.” But the similarities between Mishima—who was working decades before the internet so couldn’t have predicted its influence—and Flattery’s work show that she approaches this as an older, more fundamental problem. She treats the unhinged behavior that has become so common as a facet of human nature, rather than technological manipulation. Social media and influencer culture can tend to be viewed as frivolous topics. Certainly they are often covered in such a fashion, but Flattery uses them as an entry point to profound questions about who and what our culture values, and what this says about us.

But while Mishima takes a nihilistic view of human nature, which can be flattening, Flattery says something more hopeful, and more complex too. In one of the early chapters, in 2010, Mae meets her old school friend Maud in the street. Maud has a rich husband and a comfortable, even enviable, life. She seems disappointed by it. They go for lunch, and Maud asks where Mae went all those years ago when she dropped out of school. This is Mae’s opportunity to boast about her wild, glamorous years in the Factory. Instead, she says: “Secretarial work. My family needed the money so I got a job.” You get the sense that has always been her story, whoever has asked. This is the happy ending Nothing Special slyly delivers. Mae doesn’t emerge triumphant; nobody adores her, she stayed behind the typewriters and never tried to be a star. In doing so she made something she felt was important. Nobody knew her role in it. But would it be so different if they had? Would they have understood?