When the next Hurricane Sandy–style superstorm slams into New York, the ability of America’s largest city to recover will depend on what happens to a place called Hunts Point. You might not immediately grasp its significance during a casual jaunt through the Bronx neighborhood; on a hot afternoon this June, auto shops blasted salsa music, and workers waited for their orders at a tamale truck near humble, low-brick buildings—one with a hand-painted mural of a forklift. But keep going, and you will eventually hear the roar of idling trucks outside what’s known as the Food Distribution Center. Inside the sprawling expanse of warehouses and refrigerated trailers is the food that, as of 2018, nourished more than 22 million people in a 50-mile radius: everything from California oranges to Chilean blueberries, Nova Scotian fish, and Australian beef. It’s whisked out each day by 13,000 trucks headed to tens of thousands of bodegas, supermarkets, restaurants, schools, food banks, and soup kitchens. “If Hunts Point is flooded, if Hunts Point is flattened, if Hunts Point gets deleted by weather, the city’s gonna starve,” said Victor Davila, a community organizer with a local group called the Point CDC, who’s lived in and adjacent to the neighborhood for most of his life.

Davila speaks with the bravado of someone coming from a place constantly ignored or underestimated by the people commuting to fancy Manhattan office towers. But he’s not exaggerating about the importance of Hunts Point—at least not by very much. It provides 35 percent of the city’s meat, 45 percent of its fish, and anywhere from 25 to 60 percent of its fresh produce.

That Hunts Point is highly vulnerable to flooding is not in dispute—nor is the fact that the risk keeps getting worse. It’s built on a peninsula surrounded on three sides by the Bronx and East Rivers. The Food Distribution Center narrowly avoided being inundated during Hurricane Sandy in 2012 because the storm hit when it was low tide in Long Island Sound; the water only made it as far as the parking lot. “However, complacency in the wake of Sandy would be a mistake, as the food supply system may not escape significant impacts in the next extreme weather event,” a city climate risk assessment noted a full decade ago. Five years after that warning, The New Republic reported that a citywide plan to protect the market was struggling with funding and implementation. Precious little has been accomplished since then. Even modest efforts to ensure that the power stays on during a storm are still years away from completion.

In other parts of New York City, memories of Sandy knocking out a power station and plunging neighborhoods into darkness, killing 43 people and causing $19 billion in economic damages, have spurred the political class into action. In an ideal world, under the radical approach known as “managed retreat,” you might relocate the most vulnerable people away from danger. But while that’s happening in some small pockets of the city, it’s a potentially fraught proposition for an urban area with a population density comparable to Mexico City. And so there are now five city-led projects costing upward of $4.5 billion that aim to elevate, fortify, and protect Lower Manhattan against extreme weather. Those plans must reckon with the flooding threats posed by sea levels that are rising roughly one inch every seven to eight years due to climate change, as well as the intensifying effects that warmer oceans and shrinking coastlines have on the fury of storms, which, in addition to surging catastrophically, can dump enough inland rain to suck unlucky bystanders into drainage pipes and turn subway stations into waterfalls.

City-led projects aimed at weatherizing New York are minuscule compared to what’s been proposed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Earlier this year, the branch of the U.S. military dangled a $52 billion strategy that entailed building more than a dozen movable sea barriers along with miles of concrete seawalls, elevated promenades, and other flood protection measures. It’s the sort of massive undertaking that requires local, state, and federal approval, and could take years, if not decades, to ever become reality.

Startlingly, given the price tag, a preliminary version of the plan lacked virtually any defenses for Hunts Point.

That’s not the only oversight critics—from scientists to local activists to elected officials—identified in the proposal the Army Corps spent the winter and spring pitching across the five boroughs. Despite being one of the largest potential waterfront transformations in the city’s history, the plan was largely devoid of storm surge defenses for areas containing essential infrastructure, like wastewater plants that process millions of gallons of sewage, power stations that keep air conditioners running during the intense summer heat, massive public housing complexes, and coastal factories—including one site in South Brooklyn that will be used to assemble wind turbine blades as tall as the Chrysler Building. As in Hunts Point, much of the turf omitted by the Army Corps was in neighborhoods with large numbers of Black, Latino, and other nonwhite residents, many of whom earn some of the city’s lowest incomes. A letter last spring from state policymakers in New York and New Jersey, as well as the New York City mayor’s office, urged the Corps to “reconsider areas where flood protection features were proposed,” even as they broadly supported the project.

It’s a pattern repeating itself across a country that is still shockingly unwilling to confront climate catastrophe. A superstorm making landfall in Norfolk, Virginia, over the coming decades could inundate all but a slender sliver of the low-lying city. White people make up less than half the population, but their neighborhoods would receive significantly better protection than Norfolk’s lower-income Black residents under an Army Corps proposal. Likewise, an Army Corps strategy proposed for Charleston, South Carolina, a city in which more than 80 percent of homes and businesses could be underwater during the next major coastal storm surge, would barely protect a historic Black neighborhood at all. These aren’t outliers, either. A 2021 report from the NAACP concluded that Black communities across the United States “are under-protected by existing Army Corps flood infrastructure and struggle to obtain new protective infrastructure.”

It’s no secret why. Since 1983, the Army Corps has been mandated by Congress to focus in all its water-related projects primarily on ensuring that the economic benefits of protecting property exceed costs. This means that, in a place such as New York City, neighborhoods like Tribeca—which falls within the city’s most expensive zip code—would receive fortresslike concrete barriers under the current storm surge proposal, while miles of vulnerable coastline in the low-income South Bronx would largely be on their own. “By law, we have to identify the plan that maximizes national economic development,” Bryce Wisemiller, a project manager for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ New York District, told me. “Or, to use a more common term, the greatest ‘bang for the buck.’”

“Unfortunately,” he acknowledged, “we won’t be able to protect everyone. But that certainly is the goal.”

That may be inevitable in a country of more than 335 million people, but there are glaring flaws with the Army Corps’ approach. In many U.S. cities, high property values in some areas are a direct result of racist policies that clustered freeways, factories, and waste treatment facilities into others. Redlining deprived generations of Black people access to high-value homes. And the most expensive pieces of infrastructure are not necessarily the most essential to a community, especially as a tsunami of investment capital helps drive a speculative real estate frenzy in coastal cities. Relying so heavily on the logic of the market to keep U.S. cities safe from the mounting marine dangers of climate change isn’t just morally dubious—it also risks being actively counterproductive in the fight against climate tragedy.

In fact, there may be a cheaper and more effective way to keep coastal residents protected from superstorms and severe flooding than walling off wealthy neighborhoods with hulking gray fortifications and leaving lower-income industrial areas to largely fend for themselves. Advocates believe it’s possible to restore nature to polluted waterways, guard against multiple forms of flooding, give communities a reprieve from hazardous air, and heal a long legacy of systemic racism—and that decades-long projects to build seawalls are just one piece of that puzzle. Putting the most vulnerable neighborhoods at the center of coastal storm surge plans—that is, a progressive approach to climate fortification—rather than effectively treating them as an afterthought appears to be the safest option, as opposed to just a feel-good one. After all, the land around wastewater plants in low-income areas might be valued by investors at a fraction of what luxury condo towers are worth, but everyone needs to flush their toilets.

“The ripple effect it could have if we don’t protect those communities, it could basically devastate the economy,” said Nydia Velázquez, a Democratic congresswoman representing parts of Brooklyn and Queens who supports the need for a “bold resiliency plan” but wants the Army Corps to do a better job of protecting vulnerable areas.

Hurricane Sandy remains one of the most destructive storms in New York history. But a storm of similar magnitude has the potential by 2050 to cause nearly five times as much in economic losses, by one city estimate, due to the intensifying effects of rising seas and warmer oceans. If it were to hit the South Bronx during high tide, water levels could surge nearly 20 feet above normal levels, flooding close to one-third of the food center. “There will be no way to get food to the supermarkets. There will be chaos in the streets,” Davila predicted.

Focused though he is on his own home, Davila could have been speaking on behalf of millions of Americans staring down the barrel of climate terror when he added, “People seem to not understand that hurting us hurts them.”

Some of the worst flooding in U.S. history came in April 1927, when unusually heavy rains swelled the Mississippi River and ruptured a system of levees constructed by the Army Corps of Engineers in no fewer than 145 places. One observer described a “tossing, seething yellow sea as far as the eye can reach.” Hundreds drowned. Southern Black people, many of whom still lived on plantations as sharecroppers, were especially exposed. Of the nearly 637,000 people who lost their homes, 555,000 were racial or ethnic minorities. In the disaster’s aftermath, many flood survivors ended up in refugee camps operated by the National Red Cross. Reports of abuse were widespread. At one camp near Greenville, Mississippi, eyewitnesses recalled armed National Guard troops forcing people to perform labor at gunpoint. When Black refugees were caught trying to leave one camp, they were “whipped, the men using a strap taken off one of their rifles.”

The Army Corps was attacked relentlessly in Congress and mainstream newspapers—but not for the treatment of Black refugees. Critics assailed the organization’s single-minded focus on levees as a form of flood control rather than a more holistic mix that included additional measures like floodways and channel clearings. Nevertheless, the catastrophe made clear that the United States needed some kind of coordinated national flood control strategy, and Congress eventually passed the Flood Control Act in 1936, firmly establishing the Army Corps as the key federal entity charged with holding back surging floodwaters, while stipulating that the economic benefits of any project had to outweigh the costs. (In contrast to the Reagan-era revision, the original act suggested environmental and other concerns should bear roughly equal weight to economic ones.) The tension between the Corps’ mission to protect valuable real estate, and its frequent neglect of areas that don’t meet the criteria, continues to define its relationship with Black and other minority communities nearly a century later. Many people working at the agency are “aware of the historical and structural bias,” the recent NAACP report found. Yet decisions about whom to protect from flooding disasters and how to do it “are structured in ways that do not always represent the needs of low-wealth communities of color.”

To this day, there continue to be cultural clashes when a branch of the military is tasked with keeping U.S. cities dry. “Several NYC district commanders, their last gig was jumping out of an airplane,” said Daniel Zarrilli, chief climate policy adviser under former Mayor Bill de Blasio. “And now they’re in charge of New York Harbor’s coastal protections. It’s just a funny thing how we’ve chosen to do this as a country.” The sense that outsiders are parachuting into a dense urban environment they don’t fully understand and proposing to spend tens of billions of dollars on 15-foot slabs of concrete that will redefine millions of people’s relationship with the area’s rivers, bays, and Atlantic beaches has led some residents to make loaded historical analogies. “This is one of the largest projects that the Army Corps has ever worked on and proposed,” said Victoria Sanders, a research analyst at the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance. “And at that scale I think it’s very accurate to say that it compares to Robert Moses.”

Moses was the notorious urban planner who, when dominating local infrastructure policy from the 1930s to the 1960s, led a team of engineers that built many of the freeways and bridges crisscrossing the city. He also believed that Black people were “dirty,” according to Robert A. Caro’s Pulitzer Prize–winning biography The Power Broker, and frequently located his most disruptive projects in neighborhoods inhabited primarily by people of color, the residents’ wishes be damned. One of the most egregious examples is the Cross Bronx Expressway, a seven-mile road that demolished hundreds of apartment buildings and displaced over 60,000 people. South Bronx property values plummeted in its wake, many white residents fled to the suburbs, and heavy industry accumulated along the borough’s waterfront. The implications were national ones. “The Cross Bronx subsequently served as a model for cities across the U.S., which were designing their own urban freeway systems,” explains Segregation by Design, a research and advocacy project created by New York–based architect Adam Paul Susaneck that documents the unequal racial impacts of car-dependent cities.

Mychal Johnson has lived in the area for more than 20 years and is co-founder of a community group called South Bronx Unite. His group noticed that the Corps proposal, which contained miles of Harlem River floodwalls stretching around the southwest corner of the borough, didn’t seem to protect a rail line connected to a major waste management facility that processes all of the Bronx’s household garbage, up to 4,000 tons per day. “They’d never thought about it,” he claimed. If that rail line was flooded during a storm surge, “that means we’ll be inundated with the garbage that’s left at this site from all over the Bronx,” he said. (Wisemiller, for his part, said this type of feedback is crucial for the Army Corps plan: “We look forward to further dialogue with the city, as well as with those local neighborhoods.”)

Johnson said this speaks to a more fundamental problem: The Army Corps has historically been slow to take into account the needs of an area whose Black and Latino residents spend their lives breathing New York’s most polluted air so that wealthier parts of the city can function. At South Bronx Unite’s new headquarters in a walk-up on Lincoln Avenue, the group’s executive director, Arif Ullah, ticked off pollution sources within a two-mile radius: gas-burning peaker power plants (so named because they kick in when electricity use reaches peak levels), dense freeway interchanges, warehouses for Fresh Direct and FedEx visited day and night by diesel-burning freight trucks. “People are paying for this with their health and with their lives,” he said. South Bronx residents, nearly a third of whom live below the poverty line, experience some of the highest rates of death and disease from asthma in the city, and likely the entire country.

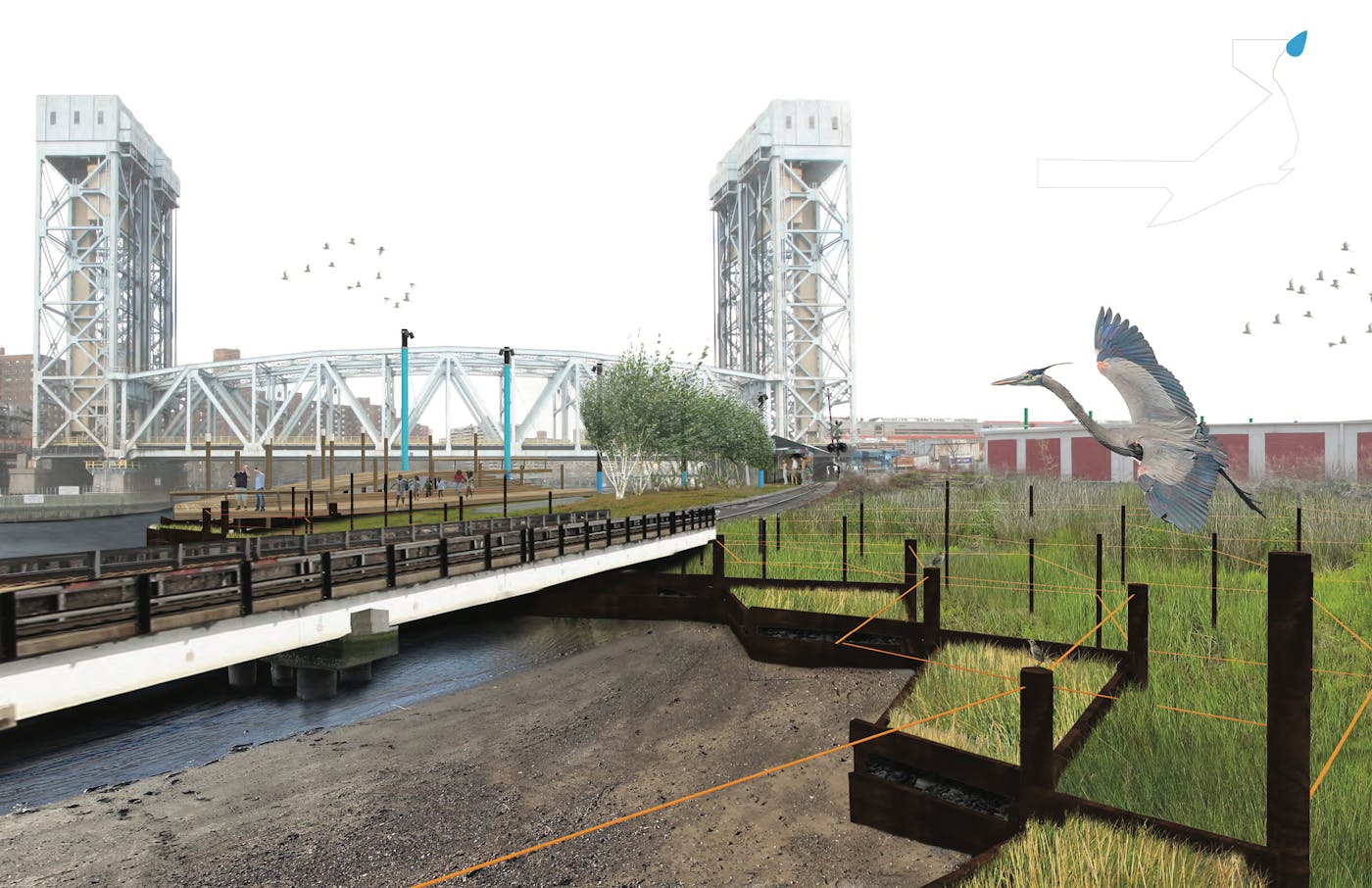

Already, it’s difficult for the 100,000 or so area residents to escape from the noise and pollution by venturing down to a coastline crammed with heavy industry—Ullah said many denizens have never visited or even seen the waterfront. And the seawalls the Army Corps is proposing for the area could serve to make residents feel all the more confined. South Bronx Unite has, for years, been pushing the city to transform six riverfront parcels into coastal parks. City planners have voiced support but haven’t yet committed to funding it. “People will be able to just let their guards down and relax, take their kids there, breathe somewhat cleaner air,” Ullah said. These green spaces, along with features like a rebuilt East River pier, would be designed to absorb the brunt of a storm surge, preventing water from inundating electric plants and other infrastructure critical for the functioning of the borough.

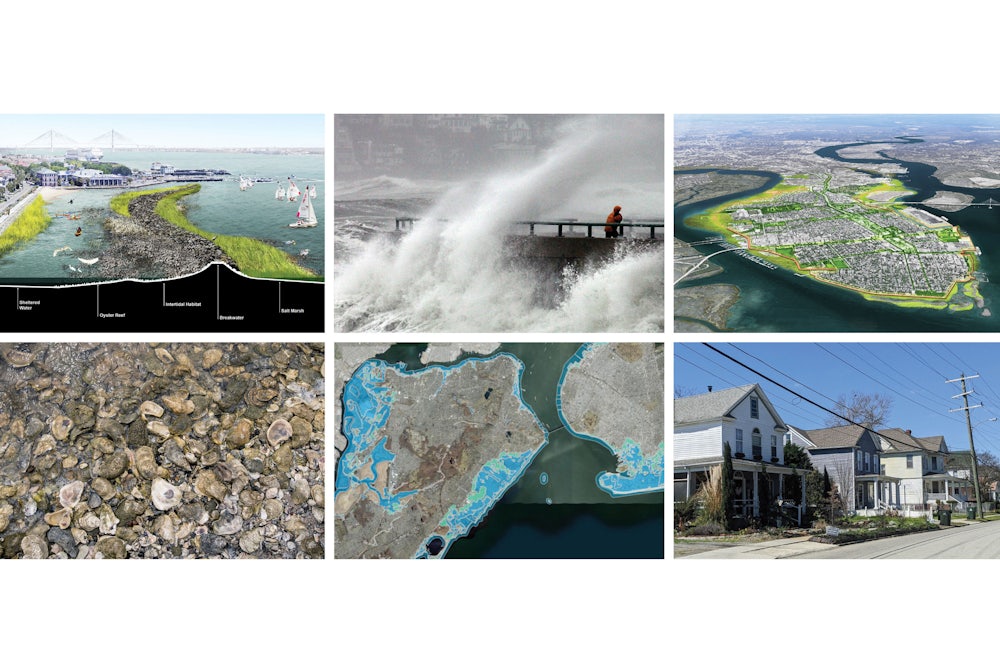

Across the country, many communities are thinking along similar lines. Restoring barrier islands, marshes, oyster reefs, mangroves, coastal forests, and other marine ecosystems to the coastlines of cities could reduce the intensity and impact of storm surges while also providing a buffer against sea-level rise and helping absorb high-intensity rainfall. “Not only can these natural solutions be implemented more quickly and often at lower costs than traditional grey infrastructure, they can also adapt to changing conditions over time,” dozens of climate experts and environmental groups wrote in a 2021 letter to the Army Corps.

Greener and more holistic fixes for flood risk are gaining mainstream acceptance. A 2020 review led by Oxford University researchers found “growing evidence” that “nature-based solutions” can reduce “damages caused by storm surges.” It cited one study looking at 52 coastal protection projects in the United States that found restoring coral reefs and salt marshes as bulwarks against flooding was “two to five times more cost-effective at lower wave heights … compared to engineered structures” such as concrete breakwaters. Yet there’s still debate about whether these measures can guard against the most extreme scenarios. Two environmental planning experts argued this summer in The New York Times that “to combat a large storm surge, like the nine feet of water pushed up by Hurricane Sandy, other nature-based solutions would require vastly more space than is available in New York Harbor.” The source for their assertion was a study conducted by the Army Corps.

Wisemiller said that his team is receptive, where it makes sense, to incorporating elements of the plans put forward by local groups. He agrees that for lower-intensity storms, “natural and nature-based solutions might be applicable,” and that in a warmer future, high-intensity rainfall needs to be taken into consideration, such as the deluge that killed 11 Queens residents whose basement homes flooded during Hurricane Ida in 2021. He also sees the value of people having green refuges along the waterfront. Ultimately, however, the Army Corps has one job to do: protect against a storm surge scenario that poses the greatest quantifiable dangers to human life and property. “That did push us into the arena of more concrete structural type measures,” Wisemiller said. One gets the sense that his organization sees itself as the domain of climate realists, willing to make the tough calls that others won’t: You may not like the barriers they’re proposing, but when a 20-foot storm surge is charging toward your neighborhood, those are the solutions that will keep you alive.

Kim Sudderth felt as if she saw history repeating itself earlier this year when she attended an Army Corps outreach meeting in Norfolk. There, she learned that her neighborhood would be receiving less protection under a $2.6 billion coastal seawall plan than the city’s more affluent, whiter communities. “I was disappointed but not surprised,” Sudderth, a city commissioner, told me. She’d moved relatively recently to Berkley, a low-income area in the city’s largely Black Southside. It’s a place rich in history—General Douglas MacArthur’s mother once called it home—with plenty of neoclassical facades and Gothic Revival churches. Sudderth loves that neighbors gather on front porches and look out for one another. She thinks there’s a lot worth protecting.

Virginia’s second-largest city is surrounded on three sides by the Elizabeth River and Chesapeake Bay. Already, some streets become impassable from flooding during high tide. In order to prepare Norfolk for a future superstorm made worse by local seas that could rise six inches by 2030, the Army Corps proposed miles of floodwalls and other protective infrastructure around some downtown neighborhoods. For Berkley and other parts of the Southside, it proposed planting coastal grasses and elevating some homes. Sudderth felt that natural solutions alone wouldn’t cut it for a city that’s almost completely flat and currently sinking, causing it to have the highest rate of relative sea-level rise on the U.S. Atlantic Coast. She wanted stronger protections. “That’s when the community banded together and decided we would speak out,” she said.

The Army Corps’ cost-benefit analysis was being imposed on an area where home values were lower than the city average. Sudderth and others argued to the city council and mayor that this supposedly neutral assessment was overlooking something crucial: Southside’s housing market had been deflated by government disinvestment and discriminatory policies, including redlining, the process by which people living in Black and minority neighborhoods were, for decades, systematically denied mortgages and housing insurance. “The economic value of the homes has been artificially diminished,” she said. “So it makes sense that almost 100 years later that the math doesn’t account for that.” Their argument won over Norfolk city council members, who, after postponing a vote twice, decided to approve a partnership with the Army Corps for its seawall proposal, provided it bolsters flood fortifications for the Southside. That must now become part of the final Army Corps plan, even as it’s still unclear who will pay for the additional protections.

In Charleston, one of the U.S. cities most vulnerable to flooding, locals have for years questioned why a $1.1 billion Army Corps surge strategy would stop at the edge of Rosemont, a predominantly Black neighborhood. Some community leaders argue the seawall could actually make flooding there worse by redirecting tidal surges, which in turn might inundate nearby industrial sites, sending toxic water through the streets. Rosemont residents are now using $400,000 in public-private grant funding to study how those dangers might be mitigated with natural flood protection options. Meanwhile, a coalition of ecologists, landscape architects, architects, and engineers known as Imagine the Wall is proposing to improve an existing Army Corps plan with green defenses like tidal wetlands and oyster reefs, along with levees, elevated roads, and strategically placed battery walls.

That may sound like years of additional study and debate at a time when we can least afford it. To some extent, it is. But proponents of these progressive survival plans say they can be deployed in a fraction of the time it takes to approve and build concrete seawalls. “There are better, more cost-effective and time-sensitive alternatives that could be implemented,” argued a Texas environmental advocacy group called Bayou City Waterkeeper in response to the Army Corps’ $34 billion proposal (which last year was approved by the U.S. Senate but remains held up in the House) to fortify one of the nation’s largest petrochemical complexes in the Houston Ship Channel near Galveston.

Many within the Army Corps are aware that its cost-benefit analysis is doing a poor job of ensuring that all Americans, no matter their race or income, are protected from the escalating flood threats of a warming planet. Michael Connor, assistant secretary of the Army for civil works, last year issued interim guidance that the agency must take a new approach that “goes beyond ‘doing no harm,’ to focus on putting the disadvantaged communities at the front and center.” That followed legislation passed by Congress in late 2020 known as the Water Resources Development Act, which ordered the Army Corps to take a more holistic view of flood risk, including sea-level rise and rain deluges, while better engaging with coastal residents most exposed to the dangers. But even with these mounting legal obligations, “they have remained relentlessly focused only on storm surge” and concrete structures to withstand it, according to Paul Gallay, project director of the Resilient Coastal Communities Project at Columbia University’s Climate School.

“To be fair to the Corps, they weren’t given the necessary resources, the necessary staff, the necessary training, the necessary direction” to carry out its evolved mission, said Gallay, who previously held policy and leadership positions at the New York state Attorney General’s office and Department of Environmental Conservation. “The Army Corps has been doing things one way for a very long time.”

As the next superstorm looms, people in America’s wealthiest neighborhoods might seem to have little to complain about. They’re often first in line for federal money to elevate their homes. They’re put at the center of Army Corps proposals, as well as rebuilding efforts after disasters. They can afford $40,000 window packages that protect against 150 miles per hour winds and costly private insurance to protect their Rolls-Royces and vintage wine collections. One private company even hires elite sailors to find refuges for luxury yachts when a storm is approaching.

Yet even residents of these communities don’t necessarily feel they’re benefiting under the current system. When the Army Corps released renderings showing what its seawall proposal could look like in lower west Manhattan, home to some of the most expensive real estate in the entire country, Pam Frederick wrote an alarmed article about it on her news site The Tribeca Citizen, deeming the idea of a concrete seawall snaking down the West Side Highway “rather shocking” and “outrageous.” The post quickly filled with comments. “Horrendous,” one read. Added another: “Was part of the mandate to come up with the ugliest looking solution possible? Did someone say, ‘let’s bring the charm of the New Jersey Turnpike to Manhattan’s West Side’?”

Frederick has lived with family in Tribeca since 2004. She still has vivid memories of how Hurricane Sandy transformed the neighborhood, recalling wind so fierce that she worried it might pry a street sign loose and turn it into a “guillotine,” and her own amazement at seeing much of a street underwater. “The water ended right at a submerged Porsche. It’s so Tribeca,” she said. But that was over a decade ago, and as she stood at Hudson River Park with the early June sun beaming down, Frederick acknowledged that the threat of another superstorm felt rather abstract. Certainly, it didn’t seem urgent enough to her to warrant blocking sight lines to the river and cutting Tribeca off from the waterfront. “The price tag really freaks me out,” she said. “To me that starts to question: ‘Why not let it flood and repair it afterwards?’”

Aesthetic concerns have been central to seawall debates nationwide. In Miami, the Army Corps proposed a $6 billion plan that would have involved elevating private waterfront mansions while building a concrete seawall through the fragile ecosystem of Biscayne Bay, as well as downtown neighborhoods. “The wall options were widely panned as ugly, environmentally destructive, and socially divisive,” a local radio station reported. Miami’s Downtown Development Authority hired an architectural firm to create renderings featuring dystopian gray walls defaced with graffiti reading “Berlin.” That helped stoke a public backlash so intense that local decision-makers last year demanded the Army Corps overhaul its entire plan. Aesthetics are also helping galvanize opposition to the Charleston proposal, with council member Mike Seekings saying in July 2022 that “unless it’s drastically amended, I don’t think it’s going anywhere.”

Zarrilli, the former climate adviser in New York, told me there’s no reason that these projects have to be eyesores, and that they could be designed so well that the average person might not even know their true purpose. That might mean a raised pedestrian promenade offering sweeping views of the coastline, or lush parks that slope up from the water. “That level of design has yet to actually happen with most of the Army Corps projects,” he conceded.

Even the most sophisticated designs can provoke public anger. Zarrilli helped oversee New York City’s $1.45 billion effort to elevate portions of East River Park, a project designed to protect 110,000 New Yorkers, including more than 28,000 low-income people in public housing, from sea-level rise and storm surges. Several years ago, when the city altered the design without properly communicating the changes to community groups—a misstep acknowledged by Zarrilli—some locals were so furious that they sued, helping push back the estimated completion date from 2023 to 2026. “There’s a clear lesson that we have to avoid that,” Zarrilli said. “But there’s also a clear lesson that these are really tough projects, adapting a 400-year-old city, a dense urban environment with hundreds of miles of shoreline.”

In other words, with climate danger escalating every year, we need to find solutions to these challenges, and while equity must be central to planning, it can’t come at the expense of not taking any action at all. “The worst thing that could happen right now, and I know some groups are calling for this, is that the Army Corps should go back to the drawing board and rethink everything,” Zarrilli said.

None of the Army Corps’ recent superstorm protection projects are going to spring up in a major city anytime soon. Proposals must go through several years of feedback and fine-tuning if and before they are presented to Congress for approval. Assuming that all goes to plan, the Army Corps predicted construction on its latest New York design might not be completed until 2044. That’s a long time to wait, given that the odds of another catastrophic superstorm striking within the next 30 years are nearly one in four, according to the Environmental Defense Fund. At the same time, the consensus—at least among political elites—in favor of bold survival plans has never been stronger. The latest iteration of the Water Resources Development Act authorized the Army Corps to spend billions on such plans and sailed through Congress last year.

For his part, Davila, the Bronx community organizer, doesn’t deny the Army Corps “is full of brilliant engineers.” But instead of waiting decades for them to design, win approval for, and build defenses, some level of government—or anyone, really—should immediately start restoring flood-reducing marshlands all along the Hunts Point waterfront and doing everything possible to protect the city’s food supply from the next superstorm, he argued. “If Manhattan gets flooded, you still get to eat, because Hunts Point didn’t [flood],” he said. “If Hunts Point gets flooded, you get to starve in a nice building in Manhattan.”

With each ton of carbon emissions emerging from a smokestack, each fraction of a degree in global temperature increase, each inch of sea-level rise, we are ratcheting toward disaster of a magnitude difficult to imagine. We know what needs to happen, and we have an increasingly firm sense of how to marry urgency and equity on America’s waterfronts. What is yet to be seen, as Davila put it, is whether our country’s leaders remain “too detached from reality to understand what they need to do for their own survival.”