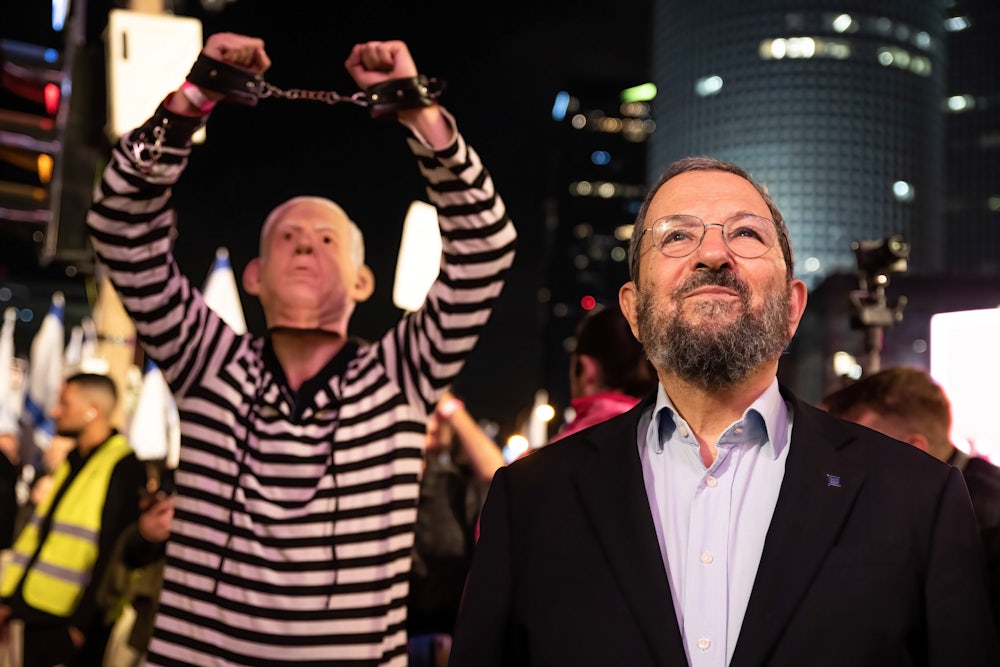

As Israeli President Isaac Herzog makes the rounds of official Washington this week, another Israeli politician familiar to many Americans continues to join in support of protests against his own government. Former Prime Minister Ehud Barak is the country’s most decorated military officer and former chief of staff of the army. As head of the Labor Party, he defeated Benjamin (Bibi) Netanyahu in a 1999 upset victory. He has served as minister of defense, foreign affairs, and the interior in left- and right-wing governments (including in a previous government headed by Bibi, from which he resigned). While he remains a controversial figure in Israel to both the left and the right, few challenge his intellect. He is also well versed in U.S. politics. Throughout our long conversation, he referred to Madison and Jefferson and at one point referenced the German sociologist Max Weber, noting that even an absolute monarch has limits to his legitimacy: “Think of Charles I in England or Louis XVI in France.” It should be clear to whom he was referring.

Barak and Netanyahu go way back. “I have known him since 1969. He was a 19-year-old soldier and then officer in Sayeret Matkal, a special forces unit, of which I was the commander. It had probably half a dozen operational officers. His elder brother, the one who was later killed in Entebbe (a 1976 Israeli commando operation to rescue over 200 Israelis held hostage at the Ugandan airport by Palestinian and German terrorists), was my deputy and one of my best friends.… Bibi was basically a good officer.” He laughs: “Sometimes I admit that I am responsible for the future Bibi problem, because I failed in convincing him to stay in a military career.”

Before the summer Knesset session ends on July 26, Israel’s government is moving to annul the “reasonableness standard,” a form of common-law doctrine that allows the high court to deny government administrative decisions if the court thinks they are beyond reason or may harm the greater good. This would remove a powerful tool from the judicial branch and could mean that government officials could freely double-deal for personal gain, decide to overturn precedent related to a broad range of human and civil rights in Israel and the occupied territories, issues of religion and state, and much more. In a system with no separation of powers, Supreme Court oversight is key to Israeli democracy. “Any law that in fact cancels the full independence of the Supreme Court turns Israel into a de facto dictatorship. The Supreme Court will be paralyzed from overruling any executive decision, however arbitrary or corrupt,” Barak explains.

In response to this bill and the promise of others to come, for more than six months, Israelis have demonstrated weekly—at least—in massive numbers, equivalent to 12 million–15 million Americans, against Bibi’s attempt regarding what opponents call regime change. Barak notes: “Since the establishment of the state, nothing like this has ever happened. Some of these people have never protested against anything.”

Barak notes that the government has labeled its plans judicial “reform,” to make them “appear benign.” He quotes the Supreme Court president, Esther Hayut, whom he defines as “not liberal—she is professional. Think of Anthony Kennedy; he was nominated as a conservative, but he would never betray his professional judgment. She immediately stood in front of the public and said this is an attempt to crush the independence of the Supreme Court and push Israel out of the family of democracies. So that’s why we are so deeply worried.”

Indeed, to hear Netanyahu’s recent interviews with U.S. media (he pointedly gives interviews these days only to Israel’s Channel 14, which is like Fox News, or to U.S. media outlets where he ends up relatively unchallenged by reporters when he offers blatant inaccuracies like claiming that Israel, like the United States, has a separation of powers and checks on the various government branches, which it doesn’t), you could wonder why all the protests. The reality is that whoever controls the government controls the Knesset, which is a single house, not bicameral. The only current check on state power is the Supreme Court and the judiciary, which Netanyahu seeks to weaken. When he riffs otherwise, Barak’s response is that Bibi, in “perfect English and [with] total disrespect to facts, seems totally committed to the new paradigm of post-truth, alternative facts, and fake news. He thinks that if you utter in a confident baritone, it makes it objectively accurate.”

Barak describes why he thinks Netanyahu created this government. “He needs to get rid of his personal criminal court case. Everyone has either private, sectorial, or lunatic reasons to stay in power. They feel the weakness of Netanyahu and try to blackmail him. That’s not the way to run a country like Israel.”

Now the pressure is building on Netanyahu. In addition to the street protests and reactions from the business sector, probably the most threatening events are snowballing actions of refusal to serve by volunteer reservists from the Air Force, cyber units, special forces, and Navy. Many of these reservists are volunteers, serving years beyond their mandated duty into their fifties and older because of their specializations. They are key players in most sophisticated Israeli military actions, Barak explains. “A government can announce a war, even if you think that it’s wrong and it risks the life of soldiers—probably your life, and you don’t agree with it. You are committed to go there and fight. The government can decide on a ceasefire and even on a peace agreement. The government has the right to do so, and you have to obey. But the government does not have the right to change the very basis of our democratic system and turn it into a de facto dictatorship.”

He continued: “It’s a mistake to ask, ‘Why do you refuse to serve?’ That’s not the case. The real aggressor, the one who changed the rules, who tried to destroy the system upon which the whole Israeli democracy is based, is Netanyahu and his inner circle. They are the provocateurs; they are the ones who cannot explain why the hell they are doing it. Never in our history as a state has Israel suffered such a destruction of value in such a short time. Netanyahu’s actions are a major threat to our economy. He personally promised the leading rating agencies, weeks ago, that he will not pass these laws in order to stop them from lowering their prediction about the Israeli economy.”

Netanyahu’s actions are based on more than his current state of mind. It’s cumulative. “Bibi is not a lightweight,” Barak observes. “He’s educated, ambitious, knowledgeable.… In public life he has certain achievements and deserves certain credit. But in recent years, not just the last three years, starting probably around 2015 when he won election against his own prediction and it coincided with a climax in the Iran challenge,” Barak suspects that a change took place.

This was a fraught time between the U.S. and Israel, when Obama forged ahead to sign the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA, with Iran (a vital security issue for Israel that is once again in play). Netanyahu went behind the White House’s back to organize against it and was harshly critical of Obama. “The way that Bibi responded to Obama caused unforgivable damage to Israel,” Barak says. “We could have used the opportunity, the challenge to turn it into an opportunity. We probably could not pull Obama out, but there was a clear readiness in the Obama administration to go very far toward Israel, to compensate us in a way, to help Israel be protected against uncertainties that were embedded into this agreement.” Netanyahu, Barak said, “destroyed his trust with Obama forever.”

As that was happening, Barak says, “Netanyahu gradually was drifting into more and more reliance on the extreme right.” Barak notes that Netanyahu “usually in the past … had a balanced group of ministers.” Bibi, often the most right-wing person in the room, would eventually accommodate those in his government to his center. Barak joined the 2009 Netanyahu government as minister of defense, over his concerns about Iran. Barak gives some insight to the Cabinet back then: “We had an inner Cabinet, an informal one. We called it the Gang of Eight, where we discussed a sensitive issue before bringing it to the government or the Cabinet table, to see whether we have an understanding among us of what’s needed. So in this gathering of the Gang of Eight, from time to time, Netanyahu had some bizarre idea. He would raise it, and he looked at Dan Meridor, the justice minister then and who is now among the protesters. Eyebrows were raised, Dan Meridor would look at Beni Begin [minister without portfolio back then—left Likud and left politics after Bibi]; Beni Begin would look at [Moshe] Yaalon [also a former IDF chief of staff and then minister of strategic affairs—now among the protesters], who then looked at me.… And Bibi saw the raised eyebrows. It would die before it was even discussed.”

Times, Barak told me, have changed dramatically: “But nowadays he’s surrounded by different people, much less experienced, with much less political gravitas. He is more and more centered on himself, especially since he has a problem with the law: breach of trust and fraud and bribery. It became a subject that accelerated his deterioration as a leader. He became more and more isolated, more and more bitter, diving into his perception of a great conspiracy around him … a ‘deep state’ gathered around the chief executive to depose him, whatever.”

One of the issues that has divided the protests is whether to include the Palestinian occupation in them or to stick strictly to matters relating to the court. This debate comes at a time when the Netanyahu government, bolstered by hard-right settler leaders, is strengthening Israel’s hold on the West Bank especially. Barak thinks the protests should not stray from their animating purpose “because this protest is against the judicial coup d’état, is a cardinal test. It’s not more important than the other ones, but it’s more urgent. Because if we, alas, lose this battle for democracy, we cannot ever fight the other ones. It will become irrelevant. We will live in a dictatorship, and dictatorships are not removed through elections. They always have their ways to make sure that in elections, they win.”

Barak’s own legacy includes a failed 2000 attempt overseen by President Clinton at Camp David to negotiate an agreement with PLO leader Yasser Arafat, for which Barak has been heavily criticized by Israel’s struggling peace camp. I ask him if he still believes in a two-state solution.

“My judgment, looking into our history and the others’ history, is that nothing is impossible once there are the right circumstances, right leadership. Even a unilateral step might suffice. Ours is a very complicated situation but could be solved,” he said. “And I add—for Israel, there is a compelling imperative for reasons that have to do not with justice for the Palestinians but our profound interest, our destiny, our future, our kind of identity. Because the issue, if you look at it from a bird’s-eye view, the issue is painful but simple. [Here] there are 15 million people now, about half Jews and half non-Jews. If there is only one political entity reigning over the whole territorial union, namely Israel, it will become inevitably either non-Jewish or nondemocratic. Because if a block of millions of Palestinians can vote, it is a binational state overnight and, within a very short period historically speaking, a binational state with a Muslim majority. That’s not the Zionist dream. If they cannot vote permanently, you cannot call it democracy. It will tear us apart and threaten our security.”

The peace process, he acknowledged, “doesn’t have a tailwind now.… I am very often blamed for helping it to happen by saying there is no partner. But then it was just an objective description of reality. We did not have a partner in Arafat. I didn’t say there could be no partner. I think it’s an old Roman saying that if you do not know which port you try to reach, no wind will take you there. So there is a need never to lose sight of the need to implement at the right moment with the right leadership and the right conditions the two-state vision, because not being able to do it is a threat to us much more severe than to the Palestinians.”

It’s perhaps ironic that the breach between Israel and the U.S. comes with one of the most pro-Israel presidents in American history. “Biden is a great friend of Israel,” Barak emphasizes, having known him for 40 years. “Long before he became vice president, he was a consistent supporter of Israel and behind many decisions that gave us huge assets in security and in intelligence, including with Obama.”

Meanwhile, the demonstrations continue. The scenario in the event that the legislation passes before the end of the summer Knesset session is fraught with complications if the bill becomes law. “So here we are. If Bibi pushes beyond the trigger of the next week or the week after, if he passes the full reasonability clause change into law, the protest will rise up to even higher levels,” he told me. “The Supreme Court will take a case to cancel it from different [human and civil rights groups]. I am confident that the court will cancel it, and that, immediately, will create a constitutional crisis where the torch will be passed to the gatekeepers: the attorney general, the head of secret services, the head of the armed forces. To the best of my judgment—I spent decades within those organizations—each one of them will turn to a legal adviser, and the legal adviser will tell them, ‘You have to go to the attorney general,’ and to consult with her, and she will tell them, ‘Obey the Supreme Court, not the government or the minister who gave you this order.’ And I’m confident they will follow.”

Barak, invoking American history from the Civil Rights Movement to the Chicago 7, applauds civil disobedience in a democracy. “We are basically defending democracy, and we are determined to fight and to win. But it will take time. I am extremely moved by the energy and enthusiasm and creativity of ideas that come from the young leaders of the more than 200 groups in the protest.” Indeed, the fervor to defend democracy in Israel now is fierce—days after I interviewed Barak, more groups joined with thousands taking to the streets in a day of action with dozens arrested and medical doctors announcing an open-ended strike. All this as the numbers of reservists refusing to serve continued to rise. “The protesters, the pilots, and everyone who is against it are the spontaneous defenders of Israeli democracy who are trying to stop the regime change. And that’s the whole thing in a nutshell.”